Thutmose III at The Battle of Megiddo › Ancient Egypt › Ancient Chinese Warfare » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Thutmose III at The Battle of Megiddo › Origins

- Ancient Egypt › Origins

- Ancient Chinese Warfare › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Thutmose III at The Battle of Megiddo › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

The ancient site of Megiddo was the scene of a number of battles in antiquity and is best known as the source of the word a rmageddon, the Greek rendering of the Hebrew Har-Megiddo ('Mount of Megiddo') from the biblical Book of Revelation 16:16.Revelation 16:16 is the only use of the word in the Bible and designates the site of the final battle between the forces of the Christian god and those of his adversary Satan. Megiddo, however, is mentioned at least 12 times in the Hebrew scriptures (the Christian Old Testament) concerning a number of military conflicts between the Israelites and various opponents.

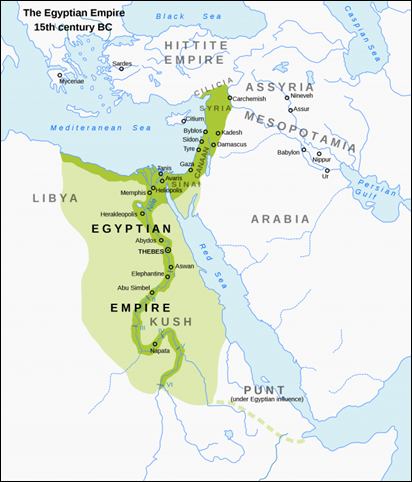

Aerial View of Megiddo

Long before the Hebrew scribes wrote of these battles, however, Megiddo was already famous for an engagement involving a coalition of kings from Canaan and Syria in rebellion against the pharaoh Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE) of Egypt.Thutmose III was one of the greatest military strategists of ancient Egypt who expanded the country's borders to establish the Egyptian Empire and elevated his nation to the status of a superpower. Although the regions which became Egyptian provinces prospered under this arrangement, they still looked for opportunities to assert their independence and regain their autonomy.

The Egyptian empire was initiated by Ahmose I (c.1570-1544 BCE) whose victory over the Hyksos of Lower Egypt marks the beginning of the period known as the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE), and every pharaoh who succeeded him maintained or enlarged the boundaries. Thutmose III, however, would go further than any others. In 20 years, he led 17 successful military campaigns, recorded on the walls of the Temple of Amun at Karnak but the most detailed account is of his first, and most famous, at Megiddo.

BACKGROUND TO THE BATTLE

Thutmose III was the son and successor of Thutmose II (1492-1479 BCE), but when his father died, he was only three years old and so his step-mother, Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE), held the throne as regent. Soon after assuming this position, however, Hatshepsut broke with tradition and assumed power. Thutmose III spent his youth at the court of Thebes, in military training, and pursuing the kind of education expected for a prince of the New Kingdom.

After her first few years as pharaoh, Hatshepsut organized no major military campaigns but kept her forces at peak efficiency and, when he proved able, promoted Thutmose III to commander of her forces. She was one of the most powerful, resourceful, and efficient monarchs in Egypt's history and, when she died, left Thutmose III a prosperous country with a well-organized and highly-trained fighting force.

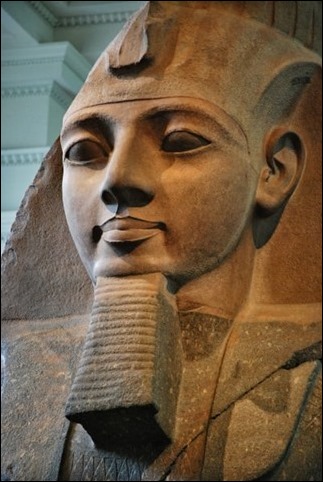

Thutmose III

Hatshepsut had maintained the empire steadily throughout her reign, but when she died, the kings of Megiddo and Kadeshrebelled against her successor whom they seem to have believed was weak. It was actually fairly common in the ancient world for subject states to rise against a new ruler in order to take advantage of the transition of power to win their independence. It is possible, in fact, that Hatshepsut anticipated this in that there seems to be some evidence that Thutmose III's first campaign had been commissioned by her; this claim is disputed, however. The coalition between the Canaanites of Megiddo and the Syrians of Kadesh attracted others dissatisfied with Egyptian rule, who gathered their forces outside the city of Megiddo in late 1458 or early 1457 BCE.

THE BATTLE OF MEGIDDO

Thutmose III wasted no time in mobilizing his forces and marching from Thebes toward the city. The army covered 150 miles in 10 days and rested at Gaza before moving on to the town of Yehem where Thutmose III halted to confer with his senior staff.There were three roads they could take from the nearby town of Aruna to reach Megiddo: a narrow pass which would require the army to march in single file and two other broader roads which would enable faster and easier movement. The generals claimed they had intelligence that the enemy was waiting for them at the end of the narrow pass and, further, progress would be slow and difficult with the vanguard reaching the battle site while the rearguard was still on the march.

Thutmose III listened to their council but disagreed with their points. According to the record of the engagement kept by his military scribe Tjaneni, Thutmose III addressed his commanders, saying:

I swear, as Ra loves me, as my father Amun favors me, as my nostrils are rejuvenated with life and satisfaction, my majesty shall proceed upon this Aruna road! Let him of you who wishes go upon these roads of which you speak and let him of you who wishes come in the following of my majesty! 'Behold', they will say, these enemies whom Ra abominates, 'has his majesty set out on another road because he has become afraid of us?' – So they will speak. (Pritchard, 177)

The generals instantly bowed to his decision and then Thutmose III addressed his army. He encouraged them to march swiftly on the narrow road and assured them that he, himself, would lead from the front, saying "I will not let my victorious army go forth ahead of my majesty in this place!" (Pritchard, 177). The chariots and wagons were dismantled and carried and the men led the horses single-file through the pass to emerge in the Qina Valley by Megiddo.

Megiddo

They found no enemy waiting for them, and in fact, the coalition had assumed that Thutmose III would choose either of the easier routes and had troops prepared to defend at both locations. Thutmose III's decision to choose the more difficult path gave him the advantage of the element of surprise. He could not attack at once, however, since the better part of his army was still strung along the Aruna pass. It would take the rearguard over seven hours of marching to catch up with their king.

Thutmose III ordered the troops to rest and refresh themselves near the Qina Brook. Throughout the night, he personally received sentry reports and gave orders for the provisioning of the troops and their placement in battle for the following day. He positioned his army so that the southern wing was on a hill above the Qina Brook and the northern wing was on a rise to the northwest of Megiddo; the king would personally command the attack and lead from the center. Tjaneni's account reads:

His majesty set forth in a chariot of fine gold, adorned with his accoutrements of combat, like Horus, the Mighty of Arm, a lord of action like Montu, the Theban, while his father Amun made strong his arms…Thereupon his majesty prevailed over them at the head of his army. Then they [the enemy] saw his majesty prevailing over them and they fled headlong to Megiddo with their faces of fear. They abandoned their horses and their chariots of gold and silver so that someone might draw them up into this town by hoisting on their garments. Now the people had shut this town against them but they let down garments to hoist them up into this town. (Pritchard, 179)

Tjaneni's report notes how, if the army had pursued the fleeing enemy across the field and cut them down in their flight, then the battle would have ended decisively that day. Instead, the soldiers "gave up their hearts to capturing the possessions of the enemy" on the field and allowed their opponents to not only reach the sanctuary of the city but mount defenses (Pritchard, 179). Thutmose III ordered a moat dug around Megiddo and a stockade built around the moat. No one from inside the city was allowed out except to surrender or if called to parley by an Egyptian officer.

The siege lasted at least seven, possibly eight, months before the leaders of the coalition surrendered the city. Thutmose III offered very generous terms, which amounted to a promise from his opponents that they would not raise another rebellion against Egypt; none of the ringleaders were executed and the city was left untouched. Thutmose III did strip the ringleaders of their positions and appointed new officials, loyal to Egypt, in their place. He also took their children as hostages back to Egypt to guarantee their good behavior. Although this may sound harsh, the hostages were well cared for and continued to live at the level of comfort they were used to. The children were educated in Egyptian culture and, when they came of age, were sent back to their lands with an appreciation for and loyalty to the Egyptian pharaoh.

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE BATTLE

The list of loot carried back to Egypt from the campaign, including prisoners of war, slaves, hostages, arms and armor, gold and silver chariots, jewels and precious metals, and livestock, would have been enough to mark it an overwhelming triumph.In addition to putting down the rebellion and enriching Egypt's treasury, however, the victory also gave Thutmose III control over northern Canaan and provided him with a base from which to launch campaigns into Mesopotamia. The great princes of the Mesopotamian cities which had not joined the coalition sent tribute to Egypt of their own accord to win favor with – and hopefully buy protection from - the great warrior-king and champion of The Battle of Megiddo, and his fame became legendary quite quickly.

THUTMOSE III'S TRIUMPH OVER THE COALITION AT MEGIDDO ESTABLISHED HIS REPUTATION EARLY & ASSURED THE SUCCESS OF ALL HIS FUTURE CAMPAIGNS.

In the following years, he would conquer Syria and the lands of the Mitanni – both of whom had been involved in the Megiddo uprising - before turning his attention to the southern borders of Egypt to defeat the Nubians and expand Egypt's holdings in that region. As at Megiddo, he always relied on the element of surprise and was never deterred by the difficulties or obstacles to victory. His triumph over the coalition at Megiddo established his reputation early and assured that the success of all his future campaigns was all but certain as the enemy would know in advance they were facing an invincible opponent.

The battle most likely suggested itself to the writer of Revelation in that the description of the forces of Satan and God in the biblical narrative are similar to those of the coalition and of Thutmose III's army in the official inscription of Tjaneni at Karnak. In both, the writers describe the victorious forces of good over the assembled coalition of evil. There can be little doubt that the scribe who wrote the biblical work was acquainted with The Battle of Megiddo since the story of Thutmose III's great victory against the combined forces of his enemies remained well known for centuries afterwards.

Ancient Egypt › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Egypt is a country in North Africa, on the Mediterranean Sea, and is home to one of the oldest civilizations on earth. The name 'Egypt' comes from the Greek Aegyptos which was the Greek pronunciation of the Egyptian name 'Hwt-Ka-Ptah' ("Mansion of the Spirit of Ptah"), originally the name of the city of Memphis. Memphis was the first capital of Egypt and a famous religious and trade centre; its high status is attested to by the Greeks alluding to the entire country by that name.

To the Egyptians themselves, their country was simply known as Kemet which means 'Black Land' so named for the rich, dark soil along the Nile River where the first settlements began. Later, the country was known as Misr which means 'country', a name still in use by Egyptians for their nation in the present day. Egypt thrived for thousands of years (from c. 8000 BCE to c. 30 BCE) as an independent nation whose culture was famous for great cultural advances in every area of human knowledge, from the arts to science to technology and religion. The great monuments which Egypt is still celebrated for reflect the depth and grandeur of Egyptian culture which influenced so many ancient civilizations, among them Greece and Rome.

One of the reasons for the enduring popularity of Egyptian culture is its emphasis on the grandeur of the human experience.Their great monuments, tombs, temples, and art work all celebrate life and stand as reminders of what once was and what human beings, at their best, are capable of achieving. Although Egypt in popular culture is often associated with death and mortuary rites, something even in these speaks to people across the ages of what it means to be a human being and the power and purpose of remembrance.

To the Egyptians, life on earth was only one aspect of an eternal journey. The soul was immortal and was only inhabiting a body on this physical plane for a short time. At death, one would meet with judgment in the Hall of Truth and, if justified, would move on to an eternal paradise known as The Field of Reeds which was a mirror image of one's life on earth. Once one had reached paradise one could live peacefully in the company of those one had loved while on earth, including one's pets, in the same neighborhood by the same steam, beneath the very same trees one thought had been lost at death. This eternal life, however, was only available to those who had lived well and in accordance with the will of the gods in the most perfect place conducive to such a goal: the land of Egypt.

Egypt has a long history which goes back far beyond the written word, the stories of the gods, or the monuments which have made the culture famous. Evidence of overgrazing of cattle, on the land which is now the Sahara Desert, has been dated to about 8000 BCE. This evidence, along with artifacts discovered, points to a thriving agricultural civilization in the region at that time. As the land was mostly arid even then, hunter-gathering nomads sought the cool of the water source of the Nile River Valley and began to settle there sometime prior to 6000 BCE.

Organized farming began in the region c. 6000 BCE and communities known as the Badarian Culture began to flourish alongside the river. Industry developed at about this same time as evidenced by faience workshops discovered at Abydos dating to c. 5500 BCE. The Badarian were followed by the Amratian, the Gerzean, and the Naqada cultures (also known as Naqada I, Naqada II, and Naqada III), all of which contributed significantly to the development of what became Egyptian civilization. The written history of the land begins at some point between 3400 and 3200 BCE when hieroglyphic script is developed by the Naqada Culture III. By 3500 BCE mummification of the dead was in practice at the city of Hierakonpolis and large stone tombs built at Abydos. The city of Xois is recorded as being already ancient by 3100-2181 BCE as inscribed on the famous Palermo Stone. As in other cultures world-wide, the small agrarian communities became centralized and grew into larger urban centers.

PROSPERITY LED TO, AMONG OTHER THINGS, AN INCREASE IN THE BREWING OF BEER, MORE LEISURE TIME FOR SPORTS, AND ADVANCES IN MEDICINE.

EARLY HISTORY OF EGYPT

The Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) saw the unification of the north and south kingdoms of Egypt under the king Menes ( also known as Meni or Manes) of Upper Egypt who conquered Lower Egypt in c. 3118 BCE or c. 3150 BCE. This version of the early history comes from the Aegyptica (History of Egypt) by the ancient historian Manetho who lived in the 3rd century BCE under the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE). Although his chronology has been disputed by later historians, it is still regularly consulted on dynastic succession and the early history of Egypt.

Manetho's work is the only source which cites Menes and the conquest and it is now thought that the man referred to by Manetho as `Menes' was the king Narmer who peacefully united Upper and Lower Egypt under one rule. Identification of Menes with Narmer is far from universally accepted, however, and Menes has been as credibly linked to the king Hor-Aha (c. 3100-3050 BCE)who succeeded him. An explanation for Menes' association with his predecessor and successor is that `Menes' is an honorific title meaning "he who endures" and not a personal name and so could have been used to refer to more than one king. The claim that the land was unified by military campaign is also disputed as the famous Narmer Palette, depicting a military victory, is considered by some scholars to be royal propaganda. The country may have first been united peacefully but this seems unlikely.

Geographical designation in Egypt follows the direction of the Nile River and so Upper Egypt is the southern region and Lower Egypt the northern area closer to the Mediterranean Sea. Narmer ruled from the city of Heirakonopolis and then from Memphis and Abydos. Trade increased significantly under the rulers of the Early Dynastic Period and elaborate mastaba tombs, precursors to the later pyramids, developed in ritual burial practices which included increasingly elaborate mummification techniques.

THE GODS

From the Pre-Dynastic Period (c. 6000-c.3150 BCE) a belief in the gods defined the Egyptian culture. An early Egyptian creation myth tells of the god Atum who stood in the midst of swirling chaos before the beginning of time and spoke creation into existence. Atum was accompanied by the eternal force of heka (magic), personified in the god Heka and by other spiritual forces which would animate the world. Heka was the primal force which infused the universe and caused all things to operate as they did; it also allowed for the central value of the Egyptian culture: ma'at, harmony and balance.

All of the gods and all of their responsibilties went back to ma'at and heka. The sun rose and set as it did and the moon traveled its course across the sky and the seasons came and went in accordance with balance and order which was possible because of these two agencies. Ma'at was also personified as a deity, the goddess of the ostrich feather, to whom every king promised his full abilities and devotion. The king was associated with the god Horus in life and Osiris in death based upon a myth which became the most popular in Egyptian history.

Osiris and his sister-wife Isis were the original monarchs who governed the world and gave the people the gifts of civilization.Osiris' brother, Set, grew jealous of him and murdered him but he was brought back to life by Isis who then bore his son Horus.Osiris was incomplete, however, and so descended to rule the underworld while Horus, once he had matured, avenged his father and defeated Set. This myth illustrated how order triumphed over chaos and would become a persistent motif in mortuary rituals and religious texts and art. There was no period in which the gods did not play an integral role in the daily lives of the Egyptians and this is clearly seen from the earliest times in the country's history.

The Pyramids

THE OLD KINGDOM

During the period known as the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE), architecture honoring the gods developed at an increased rate and some of the most famous monuments in Egypt, such as the pyramids and the Great Sphinx at Giza, were constructed. The king Djoser, who reigned c. 2670 BCE, built the first Step Pyramid at Saqqara c. 2670, designed by his chief architect and physician Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE) who also wrote one of the first medical texts describing the treatment of over 200 different diseases and arguing that the cause of disease could be natural, not the will of the gods. The Great Pyramid of Khufu (last of the seven wonders of the ancient world) was constructed during his reign (2589-2566 BCE) with the pyramids of Khafre (2558-2532 BCE) and Menkaure (2532-2503 BCE) following.

The grandeur of the pyramids on the Giza plateau, as they originally would have appeared, sheathed in gleaming white limestone, is a testament to the power and wealth of the rulers during this period. Many theories abound regarding how these monuments and tombs were constructed but modern architects and scholars are far from agreement on any single one.Considering the technology of the day, some have argued, a monument such as the Great Pyramid of Giza should not exist.Others claim, however, that the existence of such buildings and tombs suggest superior technology which has been lost to time.

There is absolutely no evidence that the monuments of the Giza plateau - or any others in Egypt - were built by slave labor nor is there any evidence to support a historical reading of the biblical Book of Exodus. Most reputable scholars today reject the claim that the pyramids and other monuments were built by slave labor although slaves of different nationalities certainly did exist in Egypt and were employed regularly in the mines. Egyptian monuments were considered public works created for the state and used both skilled and unskilled Egyptian workers in construction, all of whom were paid for their labor. Workers at the Giza site, which was only one of many, were given a ration of beer three times a day and their housing, tools, and even their level of health care have all been clearly established.

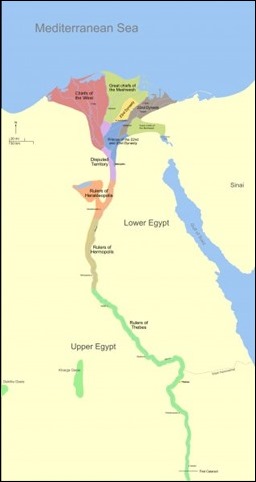

THEFIRST INTERMEDIATE PERIOD& THEHYKSOS

The era known as The First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) saw a decline in the power of the central government following its collapse. Largely independent districts with their own governors developed throughout Egypt until two great centers emerged: Hierakonpolis in Lower Egypt and Thebes in Upper Egypt. These centers founded their own dynasties which ruled their regions independently and intermittently fought with each other for supreme control until c. 2040 BCE when the Theban king Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) defeated the forces of Hierakonpolis and united Egypt under the rule of Thebes.

The stability provided by Theban rule allowed for the flourishing of what is known as the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE).The Middle Kingdom is considered Egypt's `Classical Age' when art and culture reached great heights and Thebes became the most important and wealthiest city in the country. According to the historians Oakes and Gahlin, “the Twelfth Dynasty kings were strong rulers who established control not only over the whole of Egypt but also over Nubia to the south, where several fortresses were built to protect Egyptian trading interests” (11). The first standing army was created during the Middle Kingdom by the king Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) the temple of Karnak was begun under Senruset I (c. 1971-1926 BCE), and some of the greatest art and literature of the civilization was produced. The 13th Dynasty, however, was weaker than the 12th and distracted by internal problems which allowed for a foriegn people known as the Hyksos to gain power in Lower Egypt around the Nile Delta.

The Hyksos are a mysterious people, most likely from the area of Syria / Palestine, who first appeared in Egypt c. 1800 and settled in the town of Avaris. While the names of the Hyksos kings are Semitic in origin, no definite ethnicity has been established for them. The Hyksos grew in power until they were able to take control of a significant portion of Lower Egypt by c. 1720 BCE, rendering the Theban Dynasty of Upper Egypt almsot a vassal state.

This era is known as The Second Intermediate Period (c.1782-c.1570 BCE). While the Hyksos (whose name simply means `foreign rulers') were hated by the Egyptians, they introduced a great many improvements to the culture such as the composite bow, the horse, and the chariot along with crop rotation and developments in bronze and ceramic works. At the same time the Hyksos controlled the ports of Lower Egypt, by 1700 BCE the Kingdom of Kush had risen to the south of Thebes in Nubia and now held that border. The Egyptians mounted a number of campaigns to drive the Hyksos out and subdue the Nubians but all failed until prince Ahmose I of Thebes (c.1570-1544 BCE) succeeded and unified the country under Theban rule.

THENEW KINGDOM& THEAMARNA PERIOD

Ahmose I initiated what is known as the period of the New Kingdom (c.1570- c.1069 BCE) which again saw great prosperity in the land under a strong central government. The title of pharaoh for the ruler of Egypt comes from the period of the New Kingdom; earlier monarchs were simply known as kings. Many of the Egyptian sovereigns best known today ruled during this period and the majority of the great structures of antiquity such as the Ramesseum, Abu Simbel, the temples of Karnak and Luxor, and the tombs of the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens were either created or greatly enhanced during this time.

Between 1504-1492 BCE the pharaoh Tuthmosis I consolidated his power and expanded the boundaries of Egypt to the Euphrates River in the north, Syria and Palestine to the west, and Nubia to the south. His reign was followed by Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) who greatly expanded trade with other nations, most notably the Land of Punt. Her 22-year reign was one of peace and prosperity for Egypt.

Portrait of Queen Hatshepsut

Her successor, Tuthmosis III, carried on her policies (although he tried to eradicate all memory of her as, it is thought, he did not want her to serve as a role model for other women since only males were considered worthy to rule) and, by the time of his death in 1425 BCE, Egypt was a great and powerful nation. The prosperity led to, among other things, an increase in the brewing of beer in many different varieties and more leisure time for sports. Advances in medicine led to improvements in health.

Bathing had long been an important part of the daily Egyptian's regimen as it was encouraged by their religion and modeled by their clergy. At this time, however, more elaborate baths were produced, presumably more for leisure than simply hygiene. The Kahun Gynecological Papyrus, concerning women's health and contraceptives, had been written c. 1800 BCE and, during this period, seems to have been made extensive use of by doctors. Surgery and dentistry were both practiced widely and with great skill, and beer was prescribed by physicians for ease of symptoms of over 200 different maladies.

In 1353 BCE the pharaoh Amenhotep IV succeeded to the throne and, shortly after, changed his name to Akhenaten (`living spirit of Aten') to reflect his belief in a single god, Aten. The Egyptians, as noted above, traditionally believed in many gods whose importance influenced every aspect of their daily lives. Among the most popular of these deities were Amun, Osiris, Isis, and Hathor. The cult of Amun, at this time, had grown so wealthy that the priests were almost as powerful as the pharaoh. Akhenaten and his queen, Nefertiti, renounced the traditional religious beliefs and customs of Egypt and instituted a new religion based upon the recognition of one god.

His religious reforms effectively cut the power of the priests of Amun and placed it in his hands. He moved the capital from Thebes to Amarna to further distance his rule from that of his predecessors. This is known as The Amarna Period (1353-1336 BCE) during which Amarna grew as the capital of the country and polytheistic religious customs were banned.

Among his many accomplishments, Akhenaten was the first ruler to decree statuary and a temple in honor of his queen instead of only for himself or the gods and used the money which once went to the temples for public works and parks. The power of the clergy declined sharply as that of the central government grew, which seemed to be Akhenaten's goal, but he failed to use his power for the best interest of his people. The Amarna Letters make clear that he was more concerned with his religious reforms than with foreign policy or the needs of the people of Egypt.

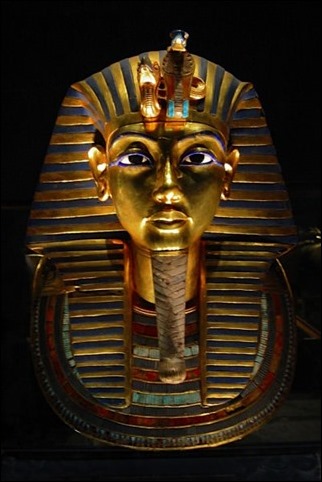

Death Mask of Tutankhamun

His reign was followed by his son, the most recognizable Egyptian ruler in the modern day, Tutankhamun, who reigned from c.1336- c.1327 BCE. He was originally named `Tutankhaten' to reflect the religious beliefs of his father but, upon assuming the throne, changed his name to `Tutankhamun' to honor the ancient god Amun. He restored the ancient temples, removed all references to his father's single deity, and returned the capital to Thebes. His reign was cut short by his death and, today, he is most famous for the intact grandeur of his tomb, discovered in 1922 CE, which became an international sensation at the time.

The greatest ruler of the New Kingdom, however, was Ramesses II (also known as Ramesses the Great, 1279-1213 BCE) who commenced the most elaborate building projects of any Egyptian ruler and who reigned so efficiently that he had the means to do so. Although the famous Battle of Kadesh of 1274 (between Ramesses II of Egypt and Muwatalli II of the Hitties) is today regarded as a draw, Ramesses considered it a great Egyptian victory and celebrated himself as a champion of the people, and finally as a god, in his many public works.

His temple of Abu Simbel (built for his queen Nefertari) depicts the battle of Kadesh and the smaller temple at the site, following Akhenaten's example, is dedicated to Ramesses favorite queen Nefertari. Under the reign of Ramesses II the first peace treaty in the world (The Treaty of Kadesh) was signed in 1258 BCE and Egypt enjoyed almost unprecedented affluence as evidenced by the number of monuments built or restored during his reign.

Ramesses II's fourth son, Khaemweset (c.1281-c.1225 BCE), is known as the "First Egyptologist" for his efforts in preserving and recording old monuments, temples, and their original owner's names. It is largely due to Khaemweset's initiative that Ramesses II's name is so prominent at so many ancient sites in Egypt. Khaemweset left a record of his own efforts, the original builder/owner of the monument or temple, and his father's name as well.

Ramesses II became known to later generations as `The Great Ancestor' and reigned for so long that he out-lived most of his children and his wives. In time, all of his subjects had been born knowing only Ramesses II as their ruler and had no memory of another. He enjoyed an exceptionally long life of 96 years, over double the average life-span of an ancient Egyptian. Upon his death, it is recorded that many feared the end of the world had come as they had known no other pharaoh and no other kind of Egypt.

Ramesses II Statue

THE DECLINE OF EGYPT & THE COMING OFALEXANDER THE GREAT

One of his successors, Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE), followed his policies but, by this time, Egypt's great wealth had attracted the attention of the Sea Peoples who began to make regular incursions along the coast. The Sea Peoples, like the Hyksos, are of unknown origin but are thought to have come from the southern Aegean area. Between 1276-1178 BCE the Sea Peoples were a threat to Egyptian security. Ramesses II had defeated them in a naval battle early in his reign as had his successor Merenptah (1213-1203 BCE). After Merenptah's death, however, they increased their efforts, sacking Kadesh, which was then under Egyptian control, and ravaging the coast. Between 1180-1178 BCE Ramesses III fought them off, finally defeating them at the Battle of Xois in 1178 BCE.

Following the reign of Ramesses III, his successors attempted to maintain his policies but increasingly met with resistance from the people of Egypt, those in the conquered territories, and, especially, the priestly class. In the years after Tutankhamun had restored the old religion of Amun, and especially during the great time of prosperity under Ramesses II, the priests of Amun had acquired large tracts of land and amassed great wealth which now threatened the central government and disrupted the unity of Egypt. By the time of Ramesses XI (1107-1077 BCE), the end of the 20th Dynasty, the government had become so weakened by the power and corruption of the clergy that the country again fractured and central administration collapsed, initiating the so-called Third Intermediate Period of c.1069-525 BCE.

Map of the Third Intermediate Period

Under the Kushite King Piye (752-722 BCE), Egypt was again unified and the culture flourished, but beginning in 671 BCE, the Assyrians under Esarhaddon began their invasion of Egypt, conquering it by 666 BCE under his successor Ashurbanipal.Having made no long-term plans for control of the country, the Assyrians left it in ruin in the hands of local rulers and abandoned Egypt to its fate. Egypt rebuilt and re-fortified, however, and this is the state the country was in when Cambyses II of Persia struck at the city of Pelusium in 525 BCE. Knowing the reverence the Egyptians held for cats (who were thought living representations of the popular goddess Bastet ) Cambyses II ordered his men to paint cats on their shields and to drive cats, and other animals sacred to the Egyptians, in front of the army toward Pelusium. The Egyptian forces surrendered and the country fell to the Persians. It would remain under Persian occupation until the coming of Alexander the Great in 332 BCE.

Alexander was welcomed as a liberator and conquered Egypt without a fight. He established the city of Alexandria and moved on to conquer Phoenicia and the rest of the Persian Empire. After his death in 323 BCE his general, Ptolemy, brought his body back to Alexandria and founded the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE). The last of the Ptolemies was Cleopatra VII who committed suicide in 30 BCE after the defeat of her forces (and those of her consort Mark Antony ) by the Romans under Octavian Caesar at the Battle of Actium (31 BCE). Egypt then became a province of Rome (30 BCE-476 CE) then of the Byzantine Empire (c. 527-646 CE) until it was conquered by the Arab Muslims under Caliph Umar in 646 CE and fell under Islamic Rule. The glory of Egypt's past, however, was re-discovered during the 18th and 19th centuries CE and has had a profound impact on the present day's understanding of ancient history and the world. Historian Will Durant expresses a sentiment felt by many:

The effect or remembrance of what Egypt accomplished at the very dawn of history has influence in every nation and every age. 'It is even possible', as Faure has said, 'that Egypt, through the solidarity, the unity, and the disciplined variety of its artistic products, through the enormous duration and the sustained power of its effort, offers the spectacle of the greatest civilization that has yet appeared on the earth.' We shall do well to equal it.(217)

Egyptian Culture and history has long held a universal fascination for people; whether through the work of early archeologists in the 19th century CE (such as Champollion who deciphered the Rosetta Stone in 1822 CE) or the famous discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun by Howard Carter in 1922 CE. The ancient Egyptian belief in life as an eternal journey, created and maintained by divine magic, inspired later cultures and later religious beliefs. Much of the iconography and the beliefs of Egyptian religion found their way into the new religion of Christianity and many of their symbols are recognizable today with largely the same meaning. It is an important testimony to the power of the Egyptian civilization that so many works of the imagination, from films to books to paintings even to religious belief, have been and continue to be inspired by its elevating and profound vision of the universe and humanity's place in it.

Ancient Chinese Warfare › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

In ancient China warfare was a means for one region to gain ascendancy over another, for the state to expand and protect its frontiers, and for usurpers to replace an existing dynasty of rulers. With armies consisting of tens of thousands of soldiers in the first millennium BCE and then hundreds of thousands in the first millennium CE, warfare became more technologically advanced and ever more destructive. Chariots gave way to cavalry, bows to crossbows and, eventually, artillery stones to gunpowder bombs. The Chinese intelligentsia may have frowned upon warfare and those who engaged in it and there were notable periods of relative peace but, as in most other ancient societies, for ordinary people it was difficult to escape the insatiable demands of war : either fight or die, be conscripted or enslaved, win somebody else's possessions or lose all of one's own.

ATTITUDES TO WARFARE

The Chinese bronze age saw a great deal of military competition between city -rulers eager to grab the riches of their neighbours, and there is no doubt that success in this endeavour legitimised reigns and increased the welfare of the victors and their people. Those who did not fight had their possessions taken, their dwellings destroyed and were usually either enslaved or killed. Indeed, much of China's history thereafter involves wars between one state or another but it is also true that warfare was perhaps a little less glorified in ancient China than it was in other ancient societies.

"NO COUNTRY HAS EVER PROFITED FROM PROTRACTED WARFARE” - SUN-TZU.

The absence of a glorification of war in China was largely due to the Confucian philosophy and its accompanying literaturewhich stressed the importance of other matters of civil life. Military treatises were written but, otherwise, stirring tales of derring-do in battle and martial themes, in general, are all rarer in Chinese mythology, literature and art than in contemporary western cultures, for example. Even such famous works as Sun-Tzu's The Art of War (5th century BCE) warned that, "No country has ever profited from protracted warfare” (Sawyer, 2007, 159). Generals and ambitious officers studied and memorised the literature on how to win at war but starting from the very top with the emperor, warfare was very often a policy of last resort. The Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) was notable for its expansion, as were some Tang dynasty emperors (618-907 CE) but, in the main, a strategy of paying off neighbours with vast tributes of silver and silk, along with a parallel exportation of “civilising” culture was seen as the best way to defend imperial China's borders. Then, if war ultimately proved unavoidable, it was better to recruit foreign troops to get on with it.

Kuan Ti

Joining the intellectuals with their disapproval of warfare were also the bureaucrats who had no time for uncultured military men. No doubt, too, the vast majority of the Chinese peasantry were never that keen on war either for it was they who had to endure conscription, heavy taxes in kind to pay for costly campaigns, and have their farms invaded and plundered.

With the emperors, the landed gentry, intellectuals and farmers all well-aware of what they could lose in war, it was, then, somewhat disappointing for them all that China, in any case, had just as many conflicts as anywhere else in the world in certain periods. One cannot ignore the common presence of fortifications in the bronze age, such chaotic centuries as the Autumn and Spring period (722-481 BCE) with its one hundred plus rival states, the Warring States period (481-221 BCE) with its incredible 358 separate conflicts or the fall of the Han when war was once again incessant between rival Chinese states. Northern steppe tribes were also constantly prodding and poking at China's borders and emperors were not averse to the odd foreign folly such as attacking ancient Korea.

WEAPONS

The great weapon of Chinese warfare throughout its history was the bow. The most common weapon of all, skill in its use was also the most esteemed. Employed since the Neolithic period, the composite version arrived during the Shang dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) and so became a much more useful and powerful component of an army's attack strategy. Bowmen often opened up the battle proceedings by firing massed volleys into the enemy and then protected the flanks of the infantry as they advanced, or their rear when they retreated. Bowmen also rode in chariots and bows were the main weapon of cavalry.

Perhaps the most distinctive and symbolic weapon of Chinese warfare was the crossbow. Introduced during the Warring States period it set China apart as a nation capable of technical innovation and the training necessary to use it effectively. The Han used it to great effect against “barbarian” tribes to expand their empire, their disciplined crossbow corps even seeing off opposing cavalry units. As with bowmen, crossbowmen were usually stationed at the flanks of infantry units. Over the centuries new designs made the crossbow lighter, able to be cocked using one hand, fire multiple bolts and fire them further, more accurately and with more power than before. Artillery versions were developed which could be mounted on a swivel base. Apart from its potential as an offensive weapon, the crossbow became a much-used means of defending well-fortified cities.

Qin Dynasty Crossbow

Swords only appeared relatively late on Chinese battlefields, probably from around 500 BCE, and never quite challenged the bow or crossbow as the prestige weapons of Chinese armies. Developing from long-bladed daggers and spearheads which were used for stabbing, the true sword was made from bronze and then, later, iron. During the Han period they became more effective with better metalworking techniques giving stronger blades with sharper cutting edges. Other weapons used by Chinese infantry included the ever-popular halberd (a mix of spear and axe), spears, javelins, daggers, and battle-axes.

Artillery was present from the Han period when the first stone-throwing, single-armed catapults were used. They were probably mostly restricted to siege warfare but were employed by both attackers and defenders. The more powerful counter-weighted catapult was not used in China until the 13th century CE. Artillery fired stones, missiles made of metal or terracotta, incendiary bombs using naphtha oil of “ Greek fire ”

(from the 10th century CE) and, from the Sung dynasty (960-1279 BCE), bombs using gunpowder. The oldest text reference to gunpowder dates to 1044 CE while a silk banner describes its use in the 9th century CE (if its dating is accurate). Gunpowder was never fully exploited in ancient China and devices using it were restricted to missiles made with a soft casing of bamboo or paper which were designed to start fires on impact. The true bomb, which dispersed lethal fragments on explosion, was not seen until the 13th century CE.

(from the 10th century CE) and, from the Sung dynasty (960-1279 BCE), bombs using gunpowder. The oldest text reference to gunpowder dates to 1044 CE while a silk banner describes its use in the 9th century CE (if its dating is accurate). Gunpowder was never fully exploited in ancient China and devices using it were restricted to missiles made with a soft casing of bamboo or paper which were designed to start fires on impact. The true bomb, which dispersed lethal fragments on explosion, was not seen until the 13th century CE.

Warring States Helmet

ARMOUR

With arrows and crossbow bolts becoming ever more lethal, it is no surprise that armour made leaps forward in design to better protect warriors. The earliest armour was undoubtedly the most impressive - tiger skins, for example - but also the least effective and by the Shang dynasty hardened leather was being worn to cover the chest and back in a more serious effort to dampen and deflect blows. By the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BCE) more flexible armour tunics were being produced made of rectangles of tanned and lacquered leather or bronze linked together with hemp or riveted. Examples of this type can be seen in the Qin warriors of the Terracotta army of the 3rd century BCE. From the Han period, iron was used more and more in armour.

HELMETS & ARMOUR, ON OCCASION, WERE DECORATED WITH PLUMES, ENGRAVINGS & PAINTINGS OF FEARSOME CREATURES.

Additional protection was provided by shields, the earliest being made only of bamboo or leather but then, like body armour, they began to incorporate metal elements. Helmets followed the same path of material evolution and usually protected the ears and back of the neck. Helmets and armour, on occasion, were decorated with plumes, engravings and paintings of fearsome creatures or beautified with additions in precious metal or ivory. Specialised armour developed for warriors in chariots who did not need to move so much and could wear full-length armoured coats. There was, too, heavy cavalry where the legs of the rider and the whole horse were protected.

CHARIOTS & CAVALRY

Chariots were used in Chinese warfare from around 1250 BCE but were seen in the greatest numbers between the 8th and 5th century BCE. First as a commander's status symbol and then as a useful shock weapon, the chariot usually carried a rider, bowman and spearman. They were very often deployed in groups of five. Pulled by two, three or four horses, they came in different versions - light and fast for moving troops around the battlefield, heavy bronze and armoured versions for punching holes in enemy ranks, those converted to carry fixed heavy crossbows, or even towered versions for commanders to better view the battle proceedings. The chariot corps could also pursue an army in retreat. Needing a wide area to turn and flat ground to function, the limitations of chariots meant they were eventually replaced by cavalry from the 4th century BCE onwards.

Chinese Qin Chariot

Cavalry was probably an innovation from the northern steppe tribes which the Chinese realised offered much more speed and mobility than chariots. The problem was to acquire the skill not only to ride the horses but also to fire weapons from them when the saddle was not much more than a blanket and the stirrup had yet to be invented. For these reasons, it was not until the Han period that cavalry became an important component of a field army. Cavalry riders were armed with a bow, lance, sword or halberd. Like chariots, cavalry was used to protect the flanks and rear of infantry formations, as a shock weapon and as a means to harass an enemy on the move or conduct hit-and-run raids.

FORTIFICATIONS

Surrounding a settlement with a protective ditch (sometimes flooded to make a moat) dates back to the 7th century BCE millennium BCE in China and the building of fortification walls using dried earth dates to the late Neolithic period. Siege warfare was not a common occurrence in China, though, until the Zhou dynasty when warfare entailed the total destruction of the enemy as opposed to just their army. By the Han period, city walls were commonly raised to a height of up to six metres and made of compacted earth. Crenellations, towers and monumental gates were another addition to a city's defence. Walls also became more weather resistant by covering the lower parts in stone to withstand local water sources being re-directed by an attacking force in order to undermine the wall. Another technique to strengthen walls was to mix in pottery sherds, plant material, branches and sand with the earth. Ditches up to 50 metres wide, often filled with water, and even a double ring of circuit wall were other techniques designed to ensure a city could withstand attack long enough for a relieving force to arrive from elsewhere.

The Great Wall of China

Not only cities but state frontiers were protected by high walls and watchtowers. The earliest may have been in the north from the 8th century BCE but the practice became a common one in the Warring States period when many different powerful states vied for control of China. Most of these structures were dismantled by the victor state, what would become the Qin dynastyfrom 221 BCE, but one wall was greatly expanded to become the Great Wall of China. Extended again by subsequent dynasties, the wall would eventually stretch some 5,000 km from Gansu province in the east to the Liaodong peninsula. The structure was not continuous but it did, for several centuries, help protect China's northern frontier against invasion from nomadic steppe tribes.

ORGANISATION & STRATEGIES

China's history is an extremely long one and each time period and dynasty saw its own practices and innovations in warfare.Still, some themes run through the history of warfare in China. Officers were often professionals (although they commonly inherited their status), ordinary troops were conscripts or captured soldiers; convicts could also be pressed into service. There were also volunteers, typically young men from noble families who joined as cavalrymen looking for adventure and glory. The organisation of an army in the field into three divisions had a long tradition. So, too, did the five-man unit, typically applied to infantry where squads were composed of two archers and three spearmen. By the Warring States period, an army was typically divided into five divisions, each represented by a flag which denoted its function:

• Red Bird - Vanguard

• Green Dragon - Left Wing

• White Tiger - Right Wing

• Black Tortoise - Rear Guard

• Great Bear Constellation - Commander & Bodyguard

When the crossbow became more common troops proficient with that weapon often formed an elite corps and other specific units were used as shock troops to help out where needed or confuse the enemy. As already noted above, archers and cavalry protected the flanks of heavier infantry and chariots, when used, could fulfill the same function or bring up the rear. Such positions, which are described as ideals in the military treatises, are confirmed by the Terracotta Army of Shi Huangti. Flags, unit banners, drums and bells were used on the battlefield to better organise troops and deploy them in the manner the commander wished.

Supporting the soldiers were dedicated officers responsible for logistics and supplying the army with the necessary food (millet, wheat and rice), water, firewood, fodder, equipment and shelter they needed while on campaign. Material was transported by river whenever possible and if not, on ox carts, horses and even wheelbarrows from the Han period onward.From the Warring States period, and especially the Han period, portions of armies were set the task of farming so as to acquire the necessary vitals that foraging, confiscation from locals or capture from the enemy could not supply. The establishment of garrisons with their own food production and improvements in supply roads and canals also went a long way to lengthening the time an army could effectively stay in the field.

Full-on infantry battles, cavalry skirmishes, reconnaissance, espionage, subterfuge, and ambush were all present in Chinese warfare. Much was made of gentlemanly etiquette in war during the Shang and Zhou periods but this was likely an invention of later writers or at best an exaggeration. Certainly, when warfare became more mobile and the stakes made higher from the 4th century BCE, a commander was expected to win with and by any means at his disposal.

One final theme which runs through much of China's history is the use of expert diviners who could study omens, observe the movement and position of celestial bodies, gauge the meaning of natural phenomena and consult calendars all in order to determine the most auspicious time and place to engage in warfare. Without these considerations, it was believed, the best weapons, men and tactics would not be enough to bring final victory.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License