Byzantine Monasticism » Abu Simbel » Achaean League » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions » Contents

- Byzantine Monasticism » Origins

- Abu Simbel » Origins

- Achaean League » Origins

Ancient civilizations » Historical places, and their characters

Byzantine Monasticism » Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

Monasticism, that is individuals devoting themselves to an ascetic life in a monastery for devotional purposes, was an ever-present feature of the Byzantine empire. Monasteries became powerful landowners and a voice to be listened to in imperial politics. From fanatical ascetics to much-appreciated wine-producers, men and women who devoted their lives to a monastic life were an important part of the community with monasteries offering all manner of services to the poor and needy, out-of-favour nobles, weary travellers, and avid bookworms. Many Byzantine monasteries are still in use, and their impressive architecture enhances views today from Athens to Sinai.

St. Catherine's Monastery, Sinai

ORIGINS & DEVELOPMENT

Leading a life of asceticism, when one denied oneself of basic comforts, was a concept seen in the Jewish faith and, of course, by Jesus himself when he had spent time in solitude in the wilderness, and in the lives of his followers such as John the Baptist. The idea was that shorn of all distractions an individual could be closer to God. In the 3rd century CE, the deserts of Egypt were a particular hotspot for wandering ascetics (aka anchorites or eremites) who lived hermit lives of self-denial, the most famous being Saint Anthony (c. 251-356 CE). Most ascetic hermits were men, but there were some women, notably the reformed prostitute Saint Mary of Egypt (c. 344 - c. 421 CE) who spent 17 years in the desert.

Monasticism developed in the 4th century CE and became more widespread from the 5th century CE when monks began to move from their lonely desert retreats and live together in monasteries closer to or actually in towns and cities. One of the earliest ascetics to begin organising monasteries for his followers was Pachomios (c. 290-346 CE), an Egyptian and former soldier who, perhaps inspired by the efficiency of Roman army camps, founded nine monasteries for men and two for women at Tabennisi in Egypt. These first communal (cenobitic) monasteries were administered following a list of rules compiled by Pachomios, and this style of communal living (koinobion), where monks lived, worked, and worshipped together in a daily routine, with all property held in common, and an abbot (hegoumenos) administering them, became the common model in the Byzantine period.

THE MOST PROMINENT EARLY SUPPORTER OF MONASTERIES IN THE BYZANTINE EMPIREDURING THE 4TH CENTURY CE WAS BASIL OF CAESAREA.

A variant on, and indeed precursor of, the communal monastery was the lavra which permitted individual monks to pursue their own independent asceticism. As opposed to the communal monasteries, in the lavra the monks lived, worked, and worshipped in their own private cells. The monks were not fully independent as they remained answerable to an archimandrite or administrator and they did join their fellow monks in occasional services in a common church. In later times the term lavrawas also applied to some ordinary communal monasteries, most famously the Great Lavra on Mount Athos (see below), founded c. 962 CE.

The most prominent early supporter of Byzantine monasteries during the 4th century CE was Basil of Caesarea (aka Saint Basil or Basil the Great) who had seen for himself the monasteries in Egypt in Syria. Basil believed that monks should not only work together for common goals but also contribute to the wider community, and he set up monasteries to that effect in Asia Minor. The monks were often supported by devout aristocrats who provided them with vacant villas so that their accommodation was not always as austere as one might imagine. There were, though, urban monasteries which did follow the principles of asceticism to the letter, following the example of the classic monasteries in remote geographical locations.

The first monastery in Constantinople was the Dalmatos, founded in the late 4th century CE, and by the mid-6th century CE, the capital had nearly 30 monasteries. In the Byzantine Empire, monasteries were largely independent affairs, and there were no specific and mutually administered orders as in the Western Church. A typical Byzantine monastery could have many facilities within its walls: a church, chapel, baths, cemetery, refectory, kitchens, accommodation, storerooms, stables, and an inn for visitors.

Iviron Monastery, Mount Athos

Mountains seemed to attract monks more than any other location, and in turn, pilgrims visited their monasteries to feel closer to their God and, in many cases, to seek miraculous interventions. Mount Sinai, Mount Auxentios, Meteora, and Mount Olympos in Bithynia with its 50 monasteries were the most celebrated monastic sites. Most monasteries were independent of each other even when in the same location, but there were sometimes monasteries which were tied together by one abbot or first monk (protos) overseeing a confederation. Perhaps the most famous of all monastic sites was on Mount Athos, east of Thessaloniki, which was probably founded in the 9th century CE, if not earlier, and which includes monasteries founded by foreign monks from Bulgaria, Armenia, Serbia, and Russia, to name a few. Mount Athos remains an important site of monasticism today and, thanks to its avoidance of destructive invasions over the centuries, is a well-preserved example of Byzantine monastic life.

Always self-sufficient by working their own land, from the 10th century CE Byzantine monasteries became even larger and wealthier, their income derived from the often vast landholdings given to them by emperors and private individuals over time, and from their preferential tax treatment by the state. Quite often a monastery's lands had no geographical connection to the monastery itself, and revenue was gained from the rent of plots or sale of smallholdings. Monasteries produced such staples as wheat, barley, pulses, wine, and oil, but they could also own potteries and mills. Profits from surpluses were ploughed back into the monastery or distributed to the poor.

THE STYLITES

Another form of monastic existence, and certainly the most bizarre, was the stylite movement. The ascetic lifestyle to beat all others, it involved a single devoted monk climbing to the top of a column (stylos) and staying there, preferably standing, for months or even years exposed to all weather and, one imagines, an equal dose of awe and ridicule from passerby. Ordinary folk were well-used to monks and nuns abstaining from life’s comforts and pleasures, and they had even seen them wearing chains or heard of ascetics locking themselves in cages, but the column stance was guaranteed to get one noticed.

BYZANTINE EMPERORS COULD BE BOTH FRIEND & FOE TO MONASTERIES - GIVING LAND RIGHTS & TAX PRIVILEGES BUT ALSO PERSECUTING THEM.

The first proponent of this extreme devotion to God was said to have been Symeon the Stylite the Elder (c. 389-459 CE). The former shepherd had already been expelled from a monastery for his extreme asceticism, and he practised for his column routine by living for a while in a disused cistern with one leg chained to a heavy stone. Symeon selected a three-metre-high column in the Syrian desert near Antioch, and there he stood day in, day out, eventually attracting such a crowd that the noise caused him to build his column higher, bringing him closer to God and 16 metres off the ground. Symeon managed to live like this for 30 years, and many other monks began to follow his example so that a whole stylite movement developed which was still going strong in the 11th century CE. When Symeon died, the site of Qal’at Sem’an became one of pilgrimage, with an octagonal church, monastery, and four basilicas built around the original column.

One the most famous Symeon imitators was Daniel the Stylite (d. 493 CE). Daniel set himself up near Constantinople but did not let his precarious position stop him contributing to ecclesiastical debates, and he even advised bishops and emperor Leo I(r. 457-474 CE). A branch of the stylite movement (literally) was the dendrites who were monks who decided to live in a tree instead of on a column. These movements were part of the trend of apophatic theology which proposed that one could come to know and understand God through personal experience provided all worldly distractions were removed.

MONASTERIES & THE STATE

The monasteries, and the monks who worked and worshipped in them, eventually became a useful means for bishops to exert pressure on their ecclesiastical rivals. Fanatically loyal monks were organised into groups to intimidate anyone who did not adhere to a bishop’s favoured dogma. Mob violence over political and religious issues was often fuelled by monks. The bishops of Alexandria were particularly noted for using monks and other such devotees as the parabalani, semi-clerical workers often misleadingly referred to as “bath attendants,” to add muscle on the streets to their sermons from the pulpit.

Theodora & Michael III

Byzantine emperors could be both friend and foe to monasteries. Many emperors gave land grants and tax privileges, but others also persecuted them, especially the iconoclast emperors. These latter were responsible for the iconoclasm movement of the 8th and 9th century CE which sought to end the veneration of icons and relics and destroy them. The monasteries, being the main producers and sponsors of such items, were targeted too. In 755 CE, for example, the Pelekete monastery on Mt. Olympus was burnt down. Many others suffered a similar fate or had land and property confiscated while monks were persecuted and paraded in ceremonies of public ridicule. The 14th century CE saw another wave of persecution, this time over the issue of Hesychasm, that is the practice of monks repeating a prayer to achieve mystical communion with God.

Although religiously independent, there is evidence that Byzantine monasteries and their residents were subject to civil law like everyone else. Local judges conducted legal investigations, and monks could even be called before the courts in Constantinople.

Emperors were well aware of the influence monasteries had on local populations. For example, rulers selected the abbots of such important monasteries as those on Mount Athos, a duty taken on by the bishop of Constantinople from the 14th century CE. Another problem was that as the number of monasteries increased so the tax revenue of the state decreased. The situation moved emperor Romanos I Lekapenos (r. 920-944 CE) to forbid the founding of new monasteries to protect the land of ordinary villagers, but it proved only a temporary stop to the seemingly inevitable spread of monasteries, such was their success and use to society as a whole.

CULTURAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Although it was not their primary purpose of existence, monks and monasteries did give back to the community in which they lived by helping the poor and providing hospitals, orphanages, public baths, and homes for the aged. Even retired aristocrats and out of favour politicians and imperial relations were welcomed. Travellers were another group who could find a room when needed. In education, too, monasteries played a prominent role, notably building up large libraries and spreading Byzantine culture when monks travelled across and outside the empire. Some (but not many) also provided schools. Monasteries looked after pilgrim sites and were great patrons of the arts, not only producing their own icons and illuminated manuscripts but also sponsoring artists and architects to embellish their buildings and those of the community with images and texts to spread the Christian message. Finally, many monks were important contributors to the study of history, especially with their collections of letters and biographies (vitae) of saints, famous people, and emperors.

Abu Simbel » Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Abu Simbel is a temple complex, originally cut into a solid rock cliff, in southern Egypt and located at the second cataract of the Nile River. The two temples which comprise the site (The Great Temple and The Small Temple) were created during the reign of Ramesses II (c. 1279 - c. 1213 BCE) either between 1264 - 1244 BCE or 1244-1224 BCE. The discrepancy in the dates is due to differing interpretations of the life of Ramesses II by modern day scholars. It is certain, based upon the extensive art work throughout the interior of the Great Temple, that the structures were created, at least in part, to celebrate Ramesses' victory over the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE. To some scholars, this indicates a probable date of 1264 BCE for the initial construction as the victory would have been fresh in the memory of the people. However, the decision to build the grand monument at that precise location, on the border with the conquered lands of Nubia, suggests to other scholars the later date of 1244 BCE in that it would have had to have been begun after the Nubian Campaigns Ramesses II undertook with his sons and was built as a symbol of Egypt's power.

ABU SIMBEL WAS SACRED TO HATHORLONG BEFORE THE TEMPLES WERE BUILT THERE.

Whichever date construction began, it is agreed that it took twenty years to create the complex and that the temples are dedicated to the gods Ra-Horakty, Ptah, and the deified Ramesses II (The Great Temple) and the goddess Hathor and Queen Nefertari, Ramesses' favourite wife (The Small Temple). While it is assumed that the name, `Abu Simbel', was the designation for the complex in antiquity, this is not so. Allegedly, the Swiss explorer Burckhardt was led to the site by a boy named Abu Simbel in 1813 CE and the site was then named after him. Burckhardt, however, was unable to uncover the site, which was buried in sand up to the necks of the grand colossi and later mentioned this experience to his friend and fellow explorer Giovanni Belzoni. It was Belzoni who uncovered and first excavated (or looted) Abu Simbel in 1817 CE and it is considered likely that it was he, not Burckhardt, who was led to the site by the young boy and who named the complex after him. As with other aspects regarding Abu Simbel (such as the date it was begun), the truth of either version of the story is open to interpretation and all that is known is that the original name for the complex, if it had a specific designation, has been lost.

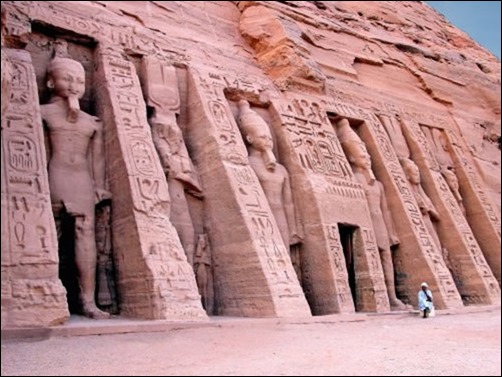

The Small Temple, Abu Simbel

THE TEMPLES

The Great Temple stands 98 feet (30 metres) high and 115 feet (35 metres) long with four seated colossi flanking the entrance, two to each side, depicting Ramesses II on his throne; each one 65 feet (20 metres) tall. Beneath these giant figures are smaller statues (still larger than life-sized) depicting Ramesses' conquered enemies, the Nubians, Libyans, and Hittites. Further statues represent his family members and various protecting gods and symbols of power. Passing between the colossi, through the central entrance, the interior of the temple is decorated with engravings showing Ramesses and Nefertari paying homage to the gods. Ramesses' great victory at Kadesh (considered by modern scholars to be more of a draw than an Egyptian triumph) is also depicted in detail across the north wall of the Hypostyle Hall. According to the scholars Oakes and Gahlin, these engravings of the events surrounding the battle,

Present a lively account in both reliefs and text. Preparations for battle are being made in the Egyptian camp. Horses are harnessed or given their fodder while one solder has his wounds dressed. The king's tent is also depicted while another scene shows a council of war between Ramesses and his officers. Two Hittite spies are captured and beaten until they reveal the true whereabouts of Muwatalli, the Hittite king. Finally, the two sides engage in battle, the Egyptians charging in neat formation while the Hittites are in confusion, chariots crashing, horses bolting and soldiers falling into the River Orontes. In the text, Ramesses takes on the whole of the Hittite army single-handed, apart from support rendered by [the god] Amunwho defends him in battle and finally hands him the victory. (208).

The Small Temple stands nearby at a height of 40 feet (12 metres) and 92 feet (28 metres) long. This temple is also adorned by colossi across the front facade, three on either side of the doorway, depicting Ramesses and his queen Nefertari (four statues of the king and two of the queen) at a height of 32 feet (10 metres). The prestige of the queen is apparent in that, usually, a female is represented on a much smaller scale than the Pharaoh while, at Abu Simbel, Nefertari is rendered the same size as Ramesses. The Small Temple is also notable in that it is the second time in ancient Egyptian history that a ruler dedicated a temple to his wife (the first time being the Pharaoh Akhenaton, 1353-1336 BCE, who dedicated a temple to his queen Nefertiti). The walls of this temple are dedicated to images of Ramesses and Nefertari making offerings to the gods and to depictions of the goddess Hathor.

A SACRED SITE

The location of the site was sacred to Hathor long before the temples were built there and, it is thought, was carefully chosen by Ramesses for this very reason. In both temples, Ramesses is recognized as a god among other gods and his choice of an already sacred localewould have strengthened this impression among the people. The temples are also aligned with the east so that, twice a year, on 21 February and 21 October, the sun shines directly into the sanctuary of The Great Temple to illuminate the statues of Ramesses and Amun. The dates are thought to correspond to Ramesses' birthday and coronation. The alignment of sacred structures with the rising or setting sun, or with the position of the sun at the solstices, was common throughout the ancient world (best known at New Grange in Irelandand Maeshowe in Scotland) but the sanctuary of The Great Temple differs from these other sites in that the statue of the god Ptah, who stands among the others, is carefully positioned so that it is never illuminated at any time. As Ptah was associated with the Egyptian underworld, his image was kept in perpetual darkness.

Ramesses II

UNDER THREAT

In the 1960's CE, the Egyptian government planned to build the Aswan High Dam on the Nile which would have submerged both temples (and also surrounding structures such as the Temple of Philae). Between 1964 and 1968 CE, a massive undertaking was carried out in which both temples were dismantled and moved 213 feet (65 metres) up onto the plateau of the cliffs they once sat below and re-built 690 feet (210 metres) to the north-west of their original location. This initiative was spearheaded by UNESCO, with a multi-national team of archaeologists, at a cost of over 40 million US dollars. Great care was taken to orient both temples in exactly the same direction as before and a man-made mountain was erected to give the impression of the temples cut into the rock cliff. According to Oakes and Gahlin:

Before the work began, a coffer dam had to be built to protect the temples from the rapidly rising water. Then the temples were sawn into blocks, taking care that the cuts were made where they would be least conspicuous when reassembled. The interior walls and ceilings were suspended from a supporting framework of reinforced concrete. When the temples were reassembled, the joins were made good by a mortar of cement and desert sand. This was done so discreetly that today it is impossible to see where the joins were made. Both temples now stand within an artificial mountain made of rubble and rock, supported by two vast domes of reinforced concrete. (207).

All of the smaller statuary and stelae which surrounded the original site of the complex were also moved and placed in their corresponding locations to the temples. Among these are stelae depicting Ramesses defeating his enemies, various gods, and a stele depicting the marriage between Ramesses and the Hittite princess Naptera, which ratified the Treaty of Kadesh. Included among these monuments is the Stele of Asha-hebsed, the foreman who organized the work force which built the complex. This stele also relates how Ramesses decided to build the complex as a lasting testament to his enduring glory and how he entrusted the work to Asha-hebsed. Today Abu Simbel is the most visited ancient site in Egypt after the Pyramids of Giza and even has its own airport to support the thousands of tourists who arrive at the site each year.

Achaean League » Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

The Achaean League (or Achaian Confederacy) was a federation of Greek city-states in the north and central parts of the Peloponnese in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE. With a combined political representation and land army, the successful early years of the League would eventually bring it into conflict with other regional powers Sparta, Macedon, and then later Rome. Defeat by the latter in 146 BCE brought the confederacy to a dramatic end.

FOUNDING & MEMBERSHIP

The League was formed in c. 281 BCE by 12 city-states in the region of Achaea who considered themselves as having a common identity (ethnos). Indeed, several of these states had already been members of a federation (koinon) in the Classical period but this had broken up c. 324 BCE. The principal founding members of the League were, then, Dyme, Patrai, Pharai, and Tritaia, all located in western Achaea in the northern Peloponnese of Greece. More Achaean cities joined in the following decade and the stature of the League grew when Sicyon, a city outside the region, joined in 251 BCE. From then on, membership steadily grew to encompass the whole of the Peloponnese.

Members enjoyed the strength in numbers of the League whilst maintaining their independence. Their primary obligation was to contribute a quota of warriors for the League’s collective army. Cities also sent representatives to meetings of the League in proportion to their status - smaller cities sent one, and larger ones could send three. Of these, the original founding and larger members continued to exert more influence and their representatives certainly carried more stature as regional statesmen. The representatives met, perhaps four times each year, on a federal council and there was also a citizen’s assembly. Up to c. 189 BCE meetings were held at the sanctuary of Zeus Homarios at Aigion and thereafter at individual city-states, presumably on a rotation basis.

THE LEAGUE GAVE ITS MEMBERS A BETTER DEFENCE AND BROUGHT SUCH BENEFITS AS ACCESS TO A COMMON JUDICIAL PROCESS AND A COMMON CURRENCY.

The representatives sent by city-states were led by the strategos (general), a position which was introduced in c. 255 BCE and held for one year. To better ensure one state did not overly dominate, the position could not be held for consecutive years. However, this did not stop some notable figures such as Philopoimen (from Megalopolis) and Aratos (from Sicyon) holding the position several times in their careers. Other important positions included the cavalry commander (hipparch), ten damiourgoiofficials, and a League secretary.

The League not only gave its members a better defence against outside aggression but also brought several non-military benefits such as access to a common judicial process and the use of a common currency and system of measurements.

SUCCESSES

As the League expanded and became more influential, so too its relations with other regional powers increased in intensity. Local rivalries existed in particular with Sparta to the south and the Aitolian League across the straits of Corinth. Even distant Macedon and Egypt began to take an interest in the League’s affairs. These relations became ever more strained as the League became more ambitious. In 243 BCE Corinth was attacked and forcibly made a member of the League. The effect of this acquisition was to weaken the Macedonian presence in the region and so allowed the League to assume more member cities, notably Megalopolis in 235 BCE.

Greek Phalanx

THE MACEDONIAN WARS

Trouble was brewing, though, as Cleomenes III of Sparta (r. 235-222 BCE) sought to expand his own influence in the region. This forced the League to seek help from Antigonos III of Macedon. Together the two allies defeated Sparta at the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BCE. As payment for their support, the acropolis of Corinth, the Acrocorinth, was given back to the Macedonians.

Then a new heavyweight power entered the scene of Greek inter-state politics: Rome. The League remained loyal to Macedon in the First Macedonian War (212-205 BCE) between the two powers. This was an unwise move as Philip V’s Macedonian army was defeated. The Achaeans then pragmatically switched sides in the Second Macedonian War (200-196 BCE) and supported Rome. This time finding itself on the winning side, the League had to carefully balance its ambitions with the new wider political situation. Around 196 BCE Rome and the League signed a treaty of alliance, quite a distinction at the time.

Achaean League c. 150 BCE

CONFLICT WITH ROME & COLLAPSE

Sparta, Elis, and Messene were made members of the League while Rome was distracted by another war, this time against Antiochos III, the Seleucid king. Again the Romans were unstoppable and their defeat of Antiochos at Thermopylae in 191 BCE and Magnesia in Asia Minor in 190 BCE left Greece ever more vulnerable to Roman dominance. A Third Macedonian War (171-167 BCE) brought another Roman victory and Greece was well on the road to become nothing more than a Roman province.

Already not best pleased by the League’s acquisition of Sparta, Rome became suspicious of its ambiguous political stance. As a consequence, Rome took 1,000 prominent Achaean hostages back to the Eternal City and in 146 BCE there was open war between the two powers in what is sometimes referred to as the Achaean War. Predictably, the Roman war machine prevailed again; Corinth was sacked and the League in its current form disbanded. The confederacy was, though, later permitted to function in a more limited way and on a more local basis. It survived as such into the 3rd century CE and perhaps beyond, occasionally forming alliances with other such groups within the Greek region of the Roman Empire.

See other Related Content for Ancient History ››

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License