Constantine IV » Sushruta » 1453: The Fall of Constantinople » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions » Contents

- Constantine IV » Who was

- Sushruta » Who was

- 1453: The Fall of Constantinople » Origins

Ancient civilizations » Historical places, and their characters

Constantine IV » Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Constantine IV ruled as emperor of the Byzantine empire from 668 to 685 CE. His reign is best remembered today for the five-year Arab siege of Constantinople from 674 CE, which the Byzantines resisted thanks to their strong fortifications and the secret weapon of Greek Fire. Although not hugely successful in other theatres, the reign of Constantine would at least stabilize the Empire, perpetuate the rule of Christianity in the East, and permit something of a revival of Byzantine fortunes under subsequent emperors.

SUCCESSION

Constantine was the eldest son of Constans II (r. 641-668 CE) and he had been crowned co-emperor, as was customary for the chosen heir, in 654 CE. Constans was unpopular with the Church for his failure to reconcile the two sides of the raging debate on dogma and on whether Christ had one will and one energy, or two of both. He did not win any admirers for his military record, either, as the Arab Caliphate inflicted a series of defeats on Byzantine armies throughout his reign. When the emperor relocated to Syracuse on Sicilyfor greater safety it was the last straw for the Byzantine aristocracy who envisaged their abandonment in Constantinople, the capital. It was no surprise, then, that Constans was assassinated - the deed done, while he took his bath, by one of his own military entourage on 15 September 668 CE, with a soap dish as the inglorious weapon.Constantine IV at first ruled alongside his brothers Herakleios and Tiberios as co-emperors. Constantine travelled to Sicily where he put down the rebellion led by Mizizios, one of the conspirators who had murdered his father. It was in the east, though, with the now annual incursions of Byzantine Asia Minor by the Arab Caliphate, that the empire was most threatened. Fortunately for the Byzantines, Constantine would prove to be,EUROPE MAY VERY WELL HAVE HAD A DIFFERENT RELIGION IF THE 7TH CENTURY CE SIEGE OF CONSTANTINOPLE HAD BEEN SUCCESSFUL.

…a wise statesman and born leader of men, the first decade of whose reign marked a watershed in the history of Christendom: the moment when, for the first time, the armies of the Crescent were turned and put to flight by those of the Cross.

(Norwich, 101)

THE SIEGE OF CONSTANTINOPLE

One of the most persistent attacks in Constantinople’s long history came with the Arab siege of 674-678 CE. Muawiya (r. 661-680 CE), the caliph and founder of the Umayyad Caliphate, had already enjoyed victories against Byzantine armies during the reign of Constans II and in 670 CE the Muslim fleet took Cyprus, Rhodes and Kos, and then moved into the northern Aegean. Next, they attacked Kyzikos (Cyzicus) on the south coast of the Sea of Marmara. Now possessing a handy peninsula from which to launch attacks, Constantinople was the next major target in 674 CE. The city’s legendary fortifications, the Theodosian Walls, and the Byzantine secret incendiary weapon of Greek Fire (a highly inflammable liquid sprayed from ships) meant that, ultimately, the five-year siege was unsuccessful.Greek Fire

During the siege, every summer the city resisted siege engines and artillery fire from huge catapults, to the frustration of the army of Muawiya. Meanwhile, the Caliphate’s armies in Asia Minor had been suffering setbacks - for example, there were attacks by the Mardaites tribesmen of Lebanon (encouraged by Constantine) - and so when his fleet was torched by Greek Fire, the caliph was forced to sign a 30-year truce with Byzantium. It was the first major defeat the Arabs had suffered since the rise of Islam. In 679 CE Muawiya was obliged to give up the Aegean islands he had conquered and pay an annual tribute which included 3,000 gold coins, 50 slaves and 50 thoroughbred horses.Constantine had preserved Christendom. If the capital had fallen then the Caliphate would have pushed on through the unprotected Balkans, across central Europe and probably even captured Rome. Consequently, Europe may very well have had a different religion if the 7th century CE siege of Constantinople had been as successful as that of the 15th century CE when the armies of Islam had sacked the jewel of the old Eastern Roman Empire.

NORTHERN & WESTERN FRONTIERS

Constantine still faced problems elsewhere, though. The Empire had fast been crumbling at the edges throughout the first half of the 7th century CE. Now the Arabs in North Africa were steadily increasing their territory at the expense of the empire and the Bulgars, led by Asparuch, were also flexing their military muscle south of the Danube. On top of that, the Slavs had attacked Thessaloniki, the empire’s second most important city. Thessaloniki was successfully defended but, after a failed Byzantine naval mission in 680 CE, the Bulgar kingdom became the first in Byzantine territory which an emperor was obliged to recognise as independent. Constantine, preferring to concentrate his armies in Asia, was constrained to sign a treaty in 681 CE which necessitated the emperor paying a handsome annual tribute to the Bulgars as a price for peace. Constantine, in any case, created a new military province (theme) in Thrace, to create a buffer defence against any future Bulgar incursions.In Italy, meanwhile, Constantine was obliged to sign a peace treaty with the ambitious Lombards who had captured Byzantine territory in the south. A similar treaty was signed with the Avars in central Europe. Greater success was enjoyed in Cilicia in 684 CE and most of the lands of the Armenians became a Byzantine protectorate at their own request. The empire had found its military feet again and stopped the rot after half a century of serious setbacks but it was still far from being secure against all-comers.

The Byzantine Empire, c. 650 CE.

THE SIXTH ECUMENICAL COUNCIL

Another notable event of Constantine’s reign was the Sixth Ecumenical Council of 680-681 CE. Constantine had communicated with Pope Agatho (678-681 CE) who enthusiastically agreed that a decision needed to be made on the Christian Church’s fundamental principles regarding the two natures of Jesus Christ, the embodiment of both the human and divine spirit. Accordingly, 174 delegates representing the Church from all parts of the empire gathered in the Domed Hall of the royal palace in Constantinople. The Council, meeting 18 times over ten months and presided over by the emperor himself, condemned both Monotheletism (the idea that Jesus Christ had a single will) and Monoenergism (that Christ had a single energy or force). Anyone who had or still disagreed with that view was condemned as a heretic. Fortunately, since the empire’s loss of Armenia and eastern territories, there were few adherents to the mono-position left anyway. The decree of the council finally reconciled the long-standing rift between the eastern and western churches.DEATH & SUCCESSORS

Constantine died of dysentery aged just 33 in 685 CE and was succeeded by his son and chosen heir Justinian II (r. 685-695 CE). Constantine left the empire in the best state it had been in for the whole of the 7th century CE. The new emperor was only 16 but, nevertheless, he enjoyed some military success during his reign. Then the usurper Leontios (r. 695-698 CE), an ambitious general backed by a wave of popular discontent at Justinian’s heavy taxes, slit the nose of the young emperor, exiled him and grabbed the throne for himself. Justinian would return, though, in 705 CE after besieging Constantinople and so ending the reign of Tiberios III. The emperor’s second spell of rule (705-711 CE) revealed him as a nasty tyrant and he proved ineffective in stopping the Arabs overrunning much of Asia Minor.Sushruta » Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

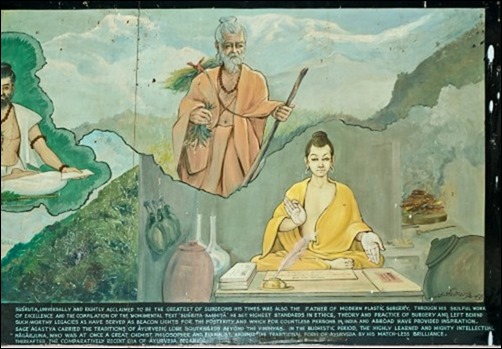

Sushruta (c. 7th or 6th century BCE) was a physician in ancient India known today as the “Father of Indian Medicine” and “Father of Plastic Surgery” for inventing and developing surgical procedures. His work on the subject, the Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta's Compendium) is considered the oldest text in the world on plastic surgery and is highly regarded as one of the Great Trilogy of Ayurvedic Medicine; the other two being the Charaka Samhita, which preceded it, and the Astanga Hridaya, which followed it.

Ayurvedic Medicine is among the oldest medical systems in the world, dating back to the Vedic Period of India (c. 5000 BCE). The term Ayurveda translates as “life knowledge” or “life science” and is the practice of holistic healing which incorporates “standard” medical knowledge with spiritual concepts and herbal remedies in treatment as well as prevention of diseases. It was practiced in India for centuries before the Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460 - c. 379 BCE), known as the Father of Medicine, was even born.

The Great Trilogy of Ayurvedic Medicine describes surgical procedures, diagnostic techniques, and treatments for various illnesses and injuries and even provides instructions for physicians on determining how long a patient will live (in the Charaka Samhita). The work of Sushruta standardized and established earlier knowledge through careful descriptions of how a physician should practice the art as well as specific procedures including performing plastic surgery reconstructions and the removal of cataracts.

The Astanga Hridaya combines the works of Charaka (c. 7th or 6th century BCE) and Sushruta, presenting a comprehensive text on both surgical and medical approaches to treatment, while also offering its own unique perspective. Sushruta’s work, however, offers the greatest insight into the medical arts of the three owing to the commentary he provides in-between or included in discussions of various ailments and treatment.

SUSHRUTA THE PHYSICIAN

Little is known of Sushruta’s life as his work focuses on the application of medical techniques and does not include any details on who he was or where he came from. Even his birth-name is unknown as “Sushruta” is an epithet meaning “renowned”. He is usually dated to the 7th or 6th centuries BCE but could have lived and worked as early as 1000 BCE; although that seems unlikely as Charaka lived shortly before him or was a contemporary. He has been associated with the Sushruta mentioned in the Mahabharata, the son of the sage Visvamitra, but this claim is not accepted by most scholars.All that is known for certain about him is that he practiced medicine in northern India around the region of modern-day Varanasi (Benares) by the banks of the Ganges River. He was regarded as a great healer and sage whose gifts were thought to have been given by the gods. According to legend, the gods passed their medical insight down to the sage Dhanvantari who taught it to his follower Divodasa, who then instructed Sushruta.SUSHRUTA SIGNIFICANTLY DEVELOPED DIFFERENT SURGICAL TECHNIQUES & INVENTED THE PRACTICE OF COSMETIC SURGERY.

The practice of surgery was already long established in India by the time of Sushruta but in a less-advanced form than what he practiced. He significantly developed different surgical techniques (such as using the head of an ant to sew sutures) and, most notably, invented the practice of cosmetic surgery. His specialty was rhinoplasty, the reconstruction of the nose, and his book instructs others on exactly how a surgeon should proceed:

The portion of the nose to be covered should be first measured with a leaf. Then a piece of skin of the required size should be dissected from the living skin of the cheek and turned back to cover the nose keeping a small pedicle attached to the cheek. The part of the nose to which the skin is to be attached should be made raw by cutting the nasal stump with a knife. The physician then should place the skin on the nose and stitch the two parts swiftly, keeping the skin properly elevated by inserting two tubes of eranda (the castor-oil plant) in the position of the nostrils so that the new nose gets proper shape. The skin thus properly adjusted, it should then be sprinkled with a powder of liquorice, red sandal-wood, and barberry plant. Finally, it should be covered with cotton and clean sesame oil should be constantly applied. When the skin has united and granulated, if the nose is too short or too long, the middle of the flap should be divided and an endeavor made to enlarge or shorten it. (Sushruta Samhita, I.16)Wine was used as an anesthetic and patients were encouraged to drink heavily before a procedure. When the patient was drunk to a point of insensibility, he or she was tied to a low-lying wooden table to prevent movement and the operation would begin with the surgeon sitting on a stool and tools on a nearby table. The use of wine led to the development of an anesthetic involving both alcohol and cannabis incense to either induce sleep or dull the senses to a stupor during procedures such as rhinoplasty.

Rhinoplasty was an especially important development in India because of the long-standing tradition of rhinotomy (amputation of the nose) as a form of punishment. Convicted criminals would often have their noses amputated to mark them as untrustworthy, but amputation was also frequently practiced on women accused of adultery – even if they were not proven guilty. Once branded in this fashion, an individual had to live with the stigma for the rest of his or her life. Reconstructive surgery, therefore, offered a hope of redemption and normalcy.

Sushruta

Sushruta attracted a number of disciples who were known as Saushrutas and were required to study for six years before they even began hands-on training in surgery. They began their studies by taking an oath to devote themselves to healing and to do no harm to others; very like the later Hippocratic Oath from Greece, which is still recited by doctors in the present day. After the students had been accepted by Sushruta, he would instruct them in surgical procedures by having them practice cutting on vegetables or dead animals to perfect the length and depth of an incision. Once students had proven themselves capable with vegetation, animal corpses, or with soft or rotting wood – and had carefully observed actual procedures on patients – they were then allowed to perform their own surgeries.These students were trained by their master in every aspect of the medical arts, including anatomy. Since there was no prohibition on dissection of corpses, as there was in Europefor centuries, physicians could work on the dead in order to better understand how to help the living. Sushruta suggests placing the corpse in a cage (to protect it from animals) and immersing it in cold water, such as a running river or stream, and then checking on its decomposition in order to study the layers of the skin, musculature, and finally the arrangement of the internal organs and skeleton. As the body decomposed and became soft, the physician could learn a great deal about how each aspect functioned and how one could help a patient live a healthier life.

SUSHRUTA ON MEDICINE & PHYSICIANS

Sushruta wrote the Sushruta Samhita as an instruction manual for physicians to treat their patients holistically. Disease, he claimed (following the precepts of Charaka), was caused by imbalance in the body, and it was the physician’s duty to help others maintain balance or to restore it if it had been lost. To this end, anyone who was engaged in the practice of medicine had to be balanced themselves. Sushruta describes the ideal medical practitioner, focusing on a nurse, in this way:That person alone is fit to nurse, or to attend the bedside of a patient, who is cool-headed and pleasant in his demeanor, does not speak ill of anyone, is strong and attentive to the requirements of the sick, and strictly and indefatigably follows the instructions of the physician. (I.34)The physician’s instructions should be followed without question because of the level of knowledge and expertise in application attained. A physician should always be focused on trying to prevent disease in the body, and this can only be accomplished if one understands how the body works in every aspect. To Sushruta, the practice of medicine was a journey of understanding for which a physician required a keen intelligence in order to recognize what was necessary for good health and how to apply that knowledge in any given situation. In one passage, he makes clear his purpose – or one of his purposes – in writing his compendium:

The science of medicine is as incomprehensible as the ocean. It cannot be fully described even in hundreds and thousands of verses. Dull people who are incapable of catching the real import of the science of reasoning would fail to acquire a proper insight into the science of medicine if dealt with elaborately in thousands of verses. The occult principles of the science of medicine, as explained in these pages, would therefore sprout and grow and bear good fruits only under the congenial heat of a medical genius. A learned and experienced medical man would therefore try to understand the occult principles herein inculcated with due caution and reference to other sciences. (XIX.15)One needed to be widely read, intelligent, and above all rational, in order to practice medicine but also needed to recognize the various influences which could bear on a person’s health. Charaka had already emphasized the importance of understanding a patient’s environment and genetic markers in order to treat illness and Sushruta built upon this in encouraging his students to ask the patient questions and encourage honest answers. If a doctor could rule out environmental factors or lifestyle choices in a patient’s disease, then genetics could be considered. Sushruta, like Charaka, understood that a genetically transmitted disease might have nothing to do with the health of a patient’s parents but possibly with one or both grandparents.

If the disease was not genetic and had nothing to do with a patient’s environment, then it was most likely caused by one’s lifestyle, which had created an imbalance of the dosha (humors) of bile, phlegm, and air. Dosha were produced when the body acted on food that was eaten. A person’s diet, therefore, was considered of vital importance in maintaining health, and a vegetarian diet was encouraged. Sushruta suggests asking the patient dietary questions as well as others pertaining to exercise and even one’s thoughts and attitudes as these could also affect one’s health.ONE NEEDED TO BE WIDELY READ, INTELLIGENT, & RATIONAL, IN ORDER TO PRACTICE MEDICINE BUT ALSO NEEDED TO RECOGNIZE THE VARIOUS INFLUENCES WHICH COULD BEAR ON A PERSON’S HEALTH.

Sushruta recognized that optimal health could only be achieved through a harmony of the mind and body. This state could be maintained through proper nutrition, exercise, and rational, uplifting thought. In certain cases, however, when the patient’s imbalance was severe, surgery was considered the best course. To Sushruta, in fact, surgery was the highest good in medicine because it could produce the most positive results more quickly than other methods of treatment.

THE SUSHRUTA SAMHITA

The Sushruta Samhita devotes chapter after chapter to surgical techniques, listing over 300 surgical procedures and 120 surgical instruments in addition to the 1,120 diseases, injuries, conditions, and their treatments, and over 700 medicinal herbs and their application, taste, and efficacy, which are also dealt with in depth. It has been claimed by some scholars (such as Vigliani and Eaton) that surgery was a last resort in treatment as the ancients tried to avoid cutting into human bodies and explored other methods of healing far more often. Although there is some truth to parts of their claim, it does not apply to Sushruta. Surgery was not considered a last resort by Sushruta but actually the best means of alleviating suffering under certain conditions.In a number of chapters throughout the book, a condition is described and a treatment suggested which includes details on how a physician should perform a certain surgery from start to finish. These details, in fact, are what marks the Sushruta Samhita as distinct from the earlier Charaka Samhita: Charaka established medical knowledge and practice while Sushruta developed surgical techniques and thus founded the practice known as Salya-tantra or “surgical science”.

According to the scholars S. Saraf and R. Parihar,

The ancient surgical science was known as Salya-tantra. Salya-tantra embraces all processes aiming at the removal of factors responsible for producing pain or misery to the body or mind. Salya (salya-surgical instrument) denotes broken parts of an arrow/other sharp weapons while tantra denotes maneuver. The broken parts of the arrows or similar pointed weapons were regarded as the commonest and most dangerous objects causing wounds and requiring surgical treatment.These techniques were brought to bear on a variety of conditions ranging from plastic surgery reconstruction of the nose and cheek to hernia surgery, caesarian section birth, removal of the prostate, tooth extraction, cataract removal, treatment of wounds and internal bleeding, and many others. He further diagnosed and defined diseases of the eyes and ears, prescribed eye and ear drops, established the school of embryology, developed prosthetic limbs, and advanced knowledge of the human body through dissection and the resultant understanding of human anatomy.

Sushruta has described surgery under eight heads: Chedya (excision), Lekhya (scarification), Vedhya (puncturing), Esya (exploration), Ahrya (extraction), Vsraya (evacuation) and Sivya (Suturing). All the basic principles of plastic surgery like planning, precision, haemostasis and perfection find an important place in Sushruta's writings on this subject. Sushruta described various reconstructive methods or different types of defects like release of the skin for covering small defects, rotation of the flaps to make up for the partial loss and pedicle flaps for covering complete loss of skin from an area. (5)

Sushruta Samhita

His knowledge of how the body worked enabled him to heal without resorting to the supernatural explanation for disease or the use of charms or amulets in healing, but this is not to say that he discounted the power of a belief in higher powers. His commentaries throughout the book make clear that a physician should be aware of, and make use of, every facet of the human condition in order to treat a patient and maintain optimal health.CONCLUSION

The Sushruta Samhita touches upon virtually every aspect of the medical arts but was unknown outside of India until around the 8th century CE when it was translated into Arabic by the Caliph Mansur (c. 753-774 CE). Even then, however, the text was unknown in the West until the late 19th century CE when the so-called Bower Manuscript was discovered which mentions Sushruta by name in a list of sages and also includes a version of the Charaka Samhita.The Bower Manuscript is named for Hamilton Bower, the English army officer who purchased it in 1890 CE, and dates to between the 4th and 6th centuries CE. The existence of this text, written in Sanskrit on birch bark, suggests there may have been others – possibly many – which preserved the writings of Sushruta and other medical sages like him. Even before the discovery of the Bower Manuscript, however, British officials and soldiers in India in the 19th century CE had written home about startling surgical procedures, especially those of cosmetic surgery reconstruction, they had witnessed in the country. Their descriptions of these surgeries correspond closely with Sushruta’s instructions in his compendium.

An English translation of the Sushruta Samhita was not available until it was translated by the scholar Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna in three volumes between 1907 and 1916 CE. By this time, of course, the world at large had accepted Hippocrates as the Father of Medicine and, further, Bhishagratna’s translation did not receive the kind of international attention it deserved. Sushruta’s name remained relatively unknown until fairly recently, as Ayurvedic medical practices have become more widely accepted, and he has begun to receive recognition for his enormous contribution to the field of medicine generally and surgical practice specifically.

Sushruta’s holistic view of healing, with an emphasis on the whole patient and not just on the symptoms presented, should be familiar to anyone in the modern day. Physicians today work up a medical history of a patient based on questions asked, research possible genetic causes for a problem, and prescribe treatments ranging from medical to surgical to so-called “alternative” practices. Further, a physician’s bedside manner in the modern day is considered important in establishing trust and encouraging the success of treatment. These practices and policies are considered innovations when compared with those as recent as the mid-20th century CE, but Sushruta had already implemented them over 2,000 years ago.

1453: The Fall of Constantinople » Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

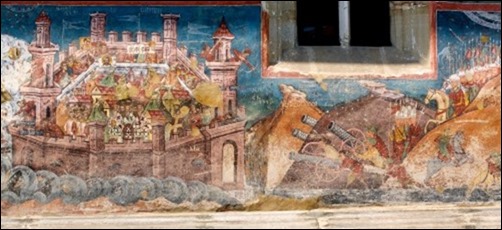

The city of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was founded by Roman emperorConstantine I in 324 CE and it acted as the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantine Empire as it has later become known, for well over 1,000 years. Although the city suffered many attacks, prolonged sieges, internal rebellions, and even a period of occupation in the 13th century CE by the Fourth Crusaders, its legendary defences were the most formidable in both the ancient and medieval worlds. It could not, though, resist the mighty cannons of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, and Constantinople, jewel and bastion of Christendom, was conquered, smashed, and looted on Tuesday, 29 May 1453 CE.The Siege of Constantinople

AN IMPREGNABLE FORTRESS

Constantinople had withstood many sieges and attacks over the centuries, notably by the Arabs between 674 and 678 CE and again between 717 and 718 CE. The great Bulgar Khans Krum (r. 802-814 CE) and Symeon (r. 893-927 CE) both attempted to attack the Byzantine capital, as did the Rus (descendants of Vikings based around Kiev) in 860 CE, 941 CE, and 1043 CE, but all failed. Another major siege was instigated by the usurper Thomas the Slav between 821 and 823 CE. All of these attacks were unsuccessful thanks to the city’s location by the sea, its naval fleet, and the secret weapon of Greek Fire (a highly inflammable liquid), and, most importantly of all, the protection of the massive Theodosian Walls.The city’s celebrated walls were a triple row of fortifications built during the reign of Theodosius II (408-450 CE) which protected the land side of the peninsula occupied by the city. They extended across the peninsula from the shores of the Sea of Marmara to the Golden Horn, eventually being fully completed in 439 CE and stretching some 6.5 kilometres. Attackers first faced a 20-metre wide and 7-metre deep ditch which could be flooded with water fed from pipes when required. Behind that was an outer wall which had a patrol track to oversee the moat. Behind this was a second wall which had regular towers and an interior terrace so as to provide a firing platform to shoot down on any enemy forces attacking the moat and first wall. Then, behind that wall was a third, much more massive, inner wall. This final defence was almost 5 metres thick, 12 metres high, and presented to the enemy 96 projecting towers. Each tower was placed around 70 metres distant from another and reached a height of 20 metres. The towers, either square or octagonal in form, could hold up to three artillery machines. The towers were so placed on the middle wall so as not to block the firing possibilities from the towers of the inner wall. The distance between the outer ditch and inner wall was 60 metres while the height difference was 30 metres.

Theodosian Walls

To take Constantinople, an army would, then, need to attack by both land and sea, but all attempts failed no matter who tried and no matter what weapons and siege engines they launched at the city. In short, Constantinople, with the greatest defences in the medieval world, was impregnable. Well, not quite. After 800 years of resisting all comers, the city’s defences were finally breached by the knights of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 CE, although the attackers got in through a carelessly left-open door and not because the fortifications themselves had failed in their purpose. Repaired and rebuilt by Michael VIII (r. 1261-1282 CE) in 1260 CE, the city remained the most difficult military nut to crack in the world, but this reputation did not in any way deter the ever-more ambitious Ottomans.CONSTANTINOPLE REMAINED THE MOST DIFFICULT MILITARY NUT TO CRACK IN THE WORLD.

THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

The Ottoman Empire had begun as a small Turkish emirate founded by Osman in Eskishehir (western Asia Minor) in the late 13th century CE, but by the early 14th century CE, it had already expanded into Thrace. With their capital at Adrianople, further captures included Thessaloniki and Serbia. In 1396 CE, at Nikopolis on the Danube, an Ottoman army defeated a Crusader army. Constantinople was the next target as Byzantium teetered on the brink of collapse and became no more than a vassal state within the Ottoman Empire. The city was attacked in 1394 CE and 1422 CE but still managed to resist. Another Crusader army was defeated in 1444 CE at Varna near the Black Sea coast. Then the new Sultan, Mehmed II (r. 1451-1481 CE), after extensive preparations such as building, extending, and occupying fortresses along the Bosporus, notably at Rumeli Hisar and Anadolu in 1452 CE, moved to finally sweep away the Byzantines and their capital.THE DEFENDERS

The crushing of the Crusader army at Varna in 1444 CE meant that the Byzantines were now on their own. No significant help could be expected from the West where the Popes were already unimpressed with the Byzantine’s unwillingness to form a union of the Church and accept their supremacy. The Venetians did send a paltry two ships and 800 men in April 1453 CE, Genoa promised another ship, and even the Pope later promised five armed ships, but the Ottomans had by then already blockaded Constantinople. The people of the city could only stock up on food and arms and hope their defences would save them yet again. According to the 15th-century CE Greek historian and eyewitness Georges Sphrantzes, the defending army was composed of fewer than 5,000 men, not a sufficient number to adequately cover the length of the city’s walls, some 19 km in total. Worse still, the once great Byzantine navy now consisted of a mere 26 ships, and most of those belonged to the Italian colonists of the city. The Byzantines were hopelessly outnumbered in men, ships, and weapons.Greek Fire

It seemed that only divine intervention could save them now, but in the many previous sieges over centuries gone by, it was believed that just such intervention had saved the city; perhaps history would be repeated. Then again, there were also ominous tales of impending doom: prophesies that proclaimed the fall of Constantinople when the emperor was called Constantine (a good number were, of course) and there was an eclipse of the moon - which there was in the days before the siege of 1453 CE.The Byzantine emperor at the time of the attack was Constantine XI (r. 1449-1453 CE), and he took personal charge of the defence along with such notable military figures as Loukas Notaras, the Kantakouzenos brothers, Nikephoros Palaiologos, and the Genoese siege expert Giovanni Giustiniani. The Byzantines had catapults and Greek Fire, the highly inflammable liquid which could be sprayed under pressure from ships or walls to torch an enemy, but the technology of warfare had moved on and the Theodosian Walls were about to get their sternest ever test.THE TECHNOLOGY OF WARFARE HAD MOVED ON & THE THEODOSIAN WALLS WERE ABOUT TO GET THEIR STERNEST EVER TEST.

THE ATTACKERS

Mehmed II had one thing that previous besiegers of Constantinople had lacked: cannons. And they were big ones. The Byzantines had actually had first option on the cannons as they had been offered them by their inventor, the Hungarian engineer named Urban, but Constantine could not meet his asking price. Urban then peddled his expertise to the Sultan, and Mehmed showed more interest and offered him four times what he was asking. These fearsome weapons were put to good use in November 1452 CE when a Venetian ship, disobeying a ban on traffic, was blown out of the water as it sailed down the Bosphorus. The captain of the vessel survived but was captured, decapitated, and then impaled on a stake. It was an ominous sign of things to come.Mehmed II

According to Georges Sphrantzes, the Ottoman army numbered 200,000 men, but modern historians prefer a more realistic figure of 60-80,000. When the army assembled at the city walls of Constantinople on 2 April 1453 CE, the Byzantines got their first glimpse of Mehmed’s cannons. The largest was 9 metres long with a gaping mouth one metre across. Already tested, it could fire a ball weighing 500 kilos over 1.5 km. So mammoth was this cannon that it took an awfully long time to load and cool it so that it could only be fired seven times a day. Still, the Ottomans had plenty of smaller cannon, each capable of firing over 100 times a day.On 5 April, Mehmed sent a demand for immediate surrender to the Byzantine emperor but received no reply. On 6 April the attack began. The Theodosian Walls were relentlessly blasted, chunk by chunk, into rubble. The defenders could do no more than fire back with their own smaller cannons by day, hold off the attackers where the cannons had punched the biggest holes, and try and repair those gaps each night as best they could, using rocks, barrels, and anything else they could get their hands on. The resulting rubble piles actually absorbed the cannon shot better than fixed walls but, eventually, one of the infantry assaults would surely get through.

A FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL

The onslaught went on for six weeks but there was some effective resistance. The Ottoman attack on the boom which blocked the city’s harbour was repelled, as were several direct assaults on the Land Walls. On 20 April, miraculously, three Genoese ships sent by the Pope and a ship carrying vital grain sent by Alphonso of Aragon managed to break through the Ottoman naval blockade and reach the defenders. Mehmed, infuriated, then got around the harbour boom by building a railed road via which 70 of his ships, loaded onto carts pulled by oxen, could be launched into the waters of the Golden Horn. The Ottomans then built a pontoon and fixed cannons to it so that they could now attack any part of the city from the sea side, not just the land. The defenders now struggled to station men where they were needed, especially along the structurally weaker sea walls.15th Century CE Ottoman Canon

Time was running out for the city but, then, a reprieve came from an unexpected quarter. Back in Asia Minor, Mehmed faced several revolts as his subjects became unruly while their Sultan and his army were abroad. For this reason, Mehmed offered Constantine a deal: pay tribute and he would withdraw. The emperor refused, and Mehmed gave the news to his men that now, when the city fell, as surely it would, they could plunder whatever they wished from one of the richest cities in the world.Mehmed launched a massive go-for-broke, throw-everything-at-them assault at dawn on 29 May. First to be sent in after the usual cannon barrage were the second-rate troops, then a second wave was launched with better-armed troops, and, finally, a third wave attacked the walls, this time composed of the Janissaries - the well-trained and highly determined elite of Mehmed's army. It was during this third wave that disaster struck the Byzantines who by now were forced to employ women and children to defend the walls. Some fool had left the small Kerkoporta gate in the Land Walls open and the Janissaries did not hesitate in using it. They climbed to the top of the wall and raised the Ottoman flag, then they worked their way around to the main gate and allowed their comrades to flood into the city.

MANY OF THE CITY’S INHABITANTS COMMITTED SUICIDE RATHER THAN BE SUBJECT TO THE HORRORS OF CAPTURE & SLAVERY.

DESTRUCTION

Chaos now ensued with some of the defenders maintaining their discipline and meeting the enemy while others rushed back to their homes to defend their own families. It is at this point that Constantine was killed in the action, most likely near the Gate of St. Romanos, although, as he had discarded any indications of his status to avoid his body being used as a trophy, his demise is not known for certain. The emperor could have fled the city days before but he chose to stay with his people, and a legend soon grew up that he had not died at all but, instead, he had been magically encased in marble and buried beneath the city which he would, one day, return to rule again.Meanwhile, the rape, pillage, and destruction began. Many of the city’s inhabitants committed suicide rather than be subject to the horrors of capture and slavery. Perhaps 4,000 were killed outright, and over 50,000 were shipped off as slaves. Many sought refuge in churches and barricaded themselves in, including inside the Hagia Sophia, but these were obvious targets for their treasures, and after they were looted for their gems and precious metals, the buildings and their priceless icons were smashed, the cowering captives butchered. Uncountable art treasures were lost, books were burned, and anything with a Christian message was hacked to pieces, including frescoes and mosaics.

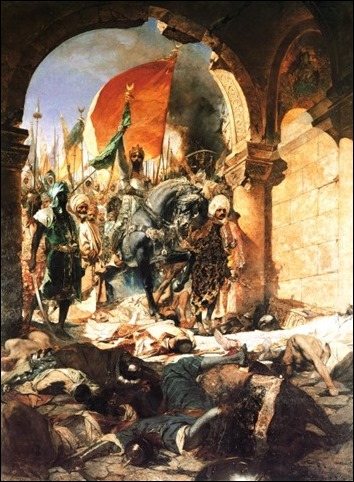

Mehmed II Conquers Constantinople

In the afternoon, Mehmed entered the city himself, called an end to the pillaging and declared that the Hagia Sophia church be immediately converted into a mosque. It was a powerful statement that the city’s role as a bastion of Christianity for twelve centuries was now over. Mehmed then rounded up the most important survivors from the city’s nobility and executed them.AFTERMATH

Constantinople was made the new Ottoman capital, the massive Golden Gate of the Theodosian Walls was made part of the castle treasury of Mehmed, while the Christian community was permitted to survive, guided by the bishop Gennadeios II. What was left of the old Byzantine empire was absorbed into Ottoman territory following the conquest of Mistra in 1460 CE and Trebizond in 1461 CE. Meanwhile, Mehmed, aged only 21 and now known as "the Conqueror", settled in for a long reign and another 28 years as Sultan. Byzantine culture would survive, especially in the arts and architecture, but the fall of Constantinople was, nevertheless, a momentous episode of world history, the end of the old Roman Empire and the last surviving link between the medieval and ancient worlds. As the historian J. J. Norwich notes,That is why five and a half centuries later, throughout the Greek world, Tuesday is still believed to be the unluckiest day of the week; why the Turkish flag still depicts not a crescent but a waning moon, reminding us that the moon was in its last quarter when Constantinople finally fell. (383)

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License

![clip_image002[1] clip_image002[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhPD6XI9LrHIkPkinRfEyhWkR1LX5ZGUSlEztxz_K85GyGHojGVVDkYg0_Tu53g8n8-zXO5pDUQBeNbYsptFwP7u3GG3mytw2h4B8xaw9bWvBDlXbKYy0o-OfB7T-rLRsNT2-5Iixzgf0Q/?imgmax=800)