Antoninus Pius › Anu › Letters to the Dead in Ancient Egypt » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Antoninus Pius › Who was

- Anu › Who was

- Letters to the Dead in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Antoninus Pius › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Donald L. Wasson

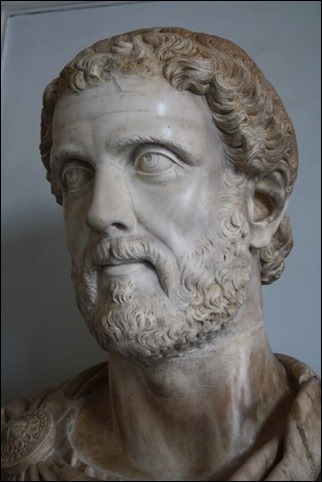

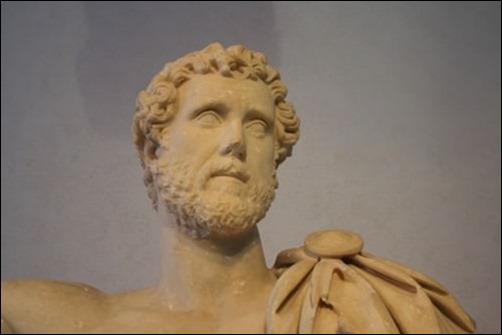

When Roman Emperor Hadrian died on July 10, 138 CE, he left, as did his predecessors, an adopted son as his successor, Antoninus Pius (138 – 161 CE). Antoninus - whose last name means dutiful - was a just and compassionate man, well-liked and respected by the common people as well as those in government. For the next 23 years his reign (second only in length to Augustus ) would be one of relative peace, assuring him a place among the Five Good Emperors.

EARLY LIFE

In actuality Antoninus Pius was not Hadrian's initial choice; he wasn't even his second. In 136 CE, with Hadrian in failing health and on the verge of suicide, he realized that without sons of his own his only option was to adopt. He chose a consul , Lucius Ceionius Commodus , as his heir. The newly adopted Lucius was immediately dispatched to Pannonia to serve as governor but unfortunately for both men, Lucius died of tuberculosis in January of 138 CE. Hadrian was at a crossroad. While he wanted the much younger Marcus Aurelius (he was only 16) to succeed him, the dying emperor realized Marcus was far too young and chose instead the highly valued and elderly Antoninus who was thought to be “safe” until the young Marcus matured.

ANTONINUS PIUS PROVED TO BE A CAPABLE, IF NOT ALWAYS DEDICATED, EMPEROR.

To everyone's surprise not only did Antoninus live a lot longer than anyone expected, but he also proved to be a capable, if not dedicated, emperor. In the words of the historian Cassius Dio, “Antoninus is said to have been of an enquiring mind and not to have held aloof from careful investigation of even small and commonplace matters.” He added, “Antoninus is admitted by all to have been noble and good, neither oppressive to the Christians nor severe to any of his other subjects...”

Although his family originally came from southern Gaul , Antoninus Pius was born in Lanuvium, 20 miles south of Rome , on September 19, 86 CE as Titus Aurelius Fulvus Boinus Arrius Antoninus, a name he shared with his father. His mother was Arria Fadilla, daughter of two-time consul Arrius Antoninus. Both his father and paternal grandfather had served as consuls.The young Antoninus was raised on a large estate at Lorium, first by his paternal grandfather and later by his maternal grandfather. The property he inherited - where he would later build a palace - made him extremely rich and even though he had no military experience, he ably served as consul, praetor, and quaestor , as well as governor in Asia Minor from 135 to 136 CE.

Little information about Antoninus and his time in power has survived. Most of what is known comes from his biographer Julius Capitolinus who wrote, “

In personal appearance he was strikingly handsome, in natural talents brilliant, in temperament kindly; he was aristocratic in countenance and calm in nature, a singularly gifted speaker and an elegant scholar, conspicuously thrifty, a conscientious landholder, gentle, generous, and mindful of other's rights. He possessed all these qualities, moreover, in the proper mean and without ostentation, and, in fine, was praiseworthy in every way and, in the minds of all good men.

On January 24, 138 CE Emperor Hadrian announced that he intended to adopt the 51 year old Antoninus as his son and heir, and on February 28, 138 CE the adoption took place. The adoption, however, came with a “condition.”. Capitolinus wrote,

The manner of his adoption, they say, was somewhat thus: At any rate, when Hadrian announced a desire to adopt him, he was given time for deciding whether he wanted to be adopted. This condition was attached to his adoption, that as Hadrian took Antoninus as his son, so he in turn should take Marcus Antoninus, his wife's nephew, and Lucius Verus .

This dual ceremony allowed Marcus to be groomed as Antoninus's successor. Later, Marcus's claim to the throne became even more secure when he married Antoninus's daughter and only surviving child, Faustina the Younger.

Antoninus Pius

EMPEROR

On July 10, 138 CE the even-tempered Antoninus Pius assumed the reins of the Roman Empire with the assumption that he would simply carry on the policies of Hadrian. Although the reason behind his last name varies, “Pius” was a name given to him by the Senate supposedly because of his loyalty to the memory of Hadrian. One of his first priorities was to have his “father” Hadrian deified, something the Senate reluctantly approved. While there were minor disturbances in Mauretania, Germany, and Egypt , he trusted his commanders to handle the situation and he never left the safety of Rome (some believe it was too expensive to leave), ruling instead from the city or his estate.

As expected he carried on many of Hadrian's policies; however, Antoninus still left his imprint on the city and empire . He insisted that the administration of the law be fair and impartial, even freeing many of the men the former emperor had imprisoned (he convinced the Senate that this had been Hadrian's wish). Trade and commerce flourished and his strict control of finances allowed for a state surplus by the time of his death. His one extravagance was the celebration of the 900th anniversary of Rome. He completed many of Hadrian's construction projects and he built monuments which included the Temple of the Deified Hadrian and, in memory of his wife, the Temple of the Deified Faustina. He also repaired many public buildings, including the decaying Colosseum . In Scotland , Hadrian's Wall was abandoned and a new one, the Antonine Wall , was built 40 miles to the north from the Firth of Clyde to the Firth of Forth - this wall would later be abandoned and the Roman ’s would retreat to Hadrian's Wall. His biographer wrote, “He gave largess to the people, and, in addition, a donation to the soldiers….Besides all this, he helped many communities to erect new buildings and to restore the old. “

On March 9, 161 CE Antonius died of a fever, supposedly after a meal of Alpine cheese. His reign would be remembered as one of relative peace. He was laid to rest in Hadrian's Mausoleum next to his wife and sons. The reins of power were handed over to his adopted sons Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Anu › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Anu (also known as An) is an early Mesopotamian sky god who was later viewed as the Father of the Gods and ruler of the heavens, a position which then passed to his son Enlil . He is the son of the couple Anshar and Kishar (heaven and earth, respectively) who were the second-born of the primordial couple Apsu and Tiamat at the beginning of the world. He was originally a Sumerian sky deity known as An (which means 'sky') who was adopted by the Akkadians c. 2375 BCE as Anu ('heaven') the all-powerful. Sargon the Great of Akkad (2334-2279 BCE) mentions Anu and Inanna in his inscriptions as legitimizing his rule or helping him in conquest . Anu is most often represented in iconography simply by a crown or crown on a throne symbolizing his status as King of the Gods, an honor and responsibility later conferred upon Enlil, Marduk (son of Enki /Ea, the god of wisdom), and Assur of the Assyrians, all of whom were believed to have been elevated by Anu and blessed by him. His consort is Antu (also known as Uras, goddess of the earth), and among their many children are the Annunaki, the gods of the earth and judges of the dead, and Nisaba , the Sumerian goddess of writing and accounts.

Although Anu is not featured prominently in many myths, he is often mentioned as a background figure. This is because, as veneration of the god progressed, he became more and more remote. Initially a sky god and one of the many younger gods born of Apsu and Tiamat, Anu gradually became the lord of the heavens above the sky and the god who ordered and maintained all aspects of existence. Along with Enlil and Enki, Anu formed a triad which governed the heavens, earth, and underworld (in one version) or, in another, heaven, the sky, and the earth. Even though he is rarely a main character in a myth, when he does appear, he plays an important role, even when that role might seem minor.

ANU IN THE ENUMA ELISH

The Babylonian epic of creation Enuma Elish (c. 1100 BCE) is the story of the birth of the gods and the formation of the world and human beings. At first, there was only the swirling waters of chaos which divided into a male principle (Apsu, symbolized by fresh water) and a female principle (Tiamat, salt water). These two gave birth to Lahmu and Lahamu, protective deities, and Anshar and Kishar who sire the younger gods. This younger group has little to do and so amuse themselves in various ways which come to anger Apsu; he cannot sleep at night for the noise and they distract him during the day. He eventually decides, after conferring with his vizier, that he must kill them.

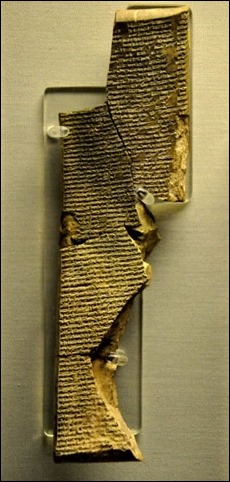

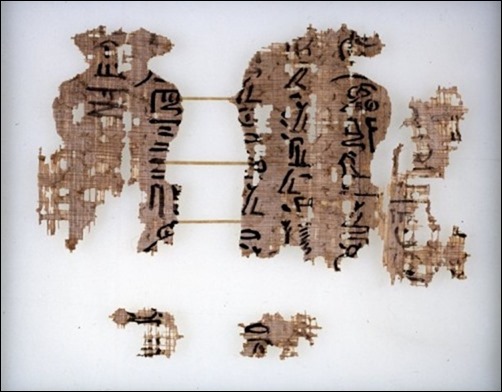

Mesopotamian Epic of Creation Tablet

Tiamat overhears her husband's conversation and warns her son (or grandson) Enki of the danger. After considering his options carefully, Enki puts Apsu into a deep sleep and kills him. Tiamat is horrified and disowns the younger gods, quickly assembling an army of demons and monsters to destroy them. The two armies clash and the younger gods are defeated and driven back again and again. At this point, Anu volunteers to go speak with Tiamat and try to resolve the problem diplomatically.

The gods seem to have every confidence in Anu's ability, but when he faces Tiamat, he is cowed and returns to the others to report his failed mission. Anu's failure, however, contributes to the younger gods' ultimate victory. The gods were confident of Anu's success, and when their hope is disappointed, they realize they have to change their ways; they can no longer maintain the old paradigm of how they believe the world should work and must accept change and find a new way of attaining their goal. It is at this point that Marduk, son of Enki, steps forward to offer himself as their champion if they will elect him their king.Marduk defeats the champion of Tiamat and kills her, but he would not have been chosen if Anu had not failed in diplomacy.Anu, then, ushers in the change in perception which allows for the ultimate victory of the gods. Once peace has been established, Marduk and his father set about the business of creation and the world and human beings are established.Among these humans are those especially skilled in wisdom and the first among the wise is the sage Adapa.

ANU IN THE MYTH OF ADAPA

The Myth of Adapa (14th century BCE), tells the story of the first man created by Enki and endowed with the god's wisdom.Although Enki loves his son he recognizes that he cannot give him everything or else he would be like a god and so he holds back the gift of immortality. Adapa has wisdom but this wisdom informs him that he will one day die and he can do nothing about that. He contents himself in service as the king of the holy city of Eridu and high priest in Enki's temple there. To serve his city, he goes out hunting for food and fishing in his boat on the sea.

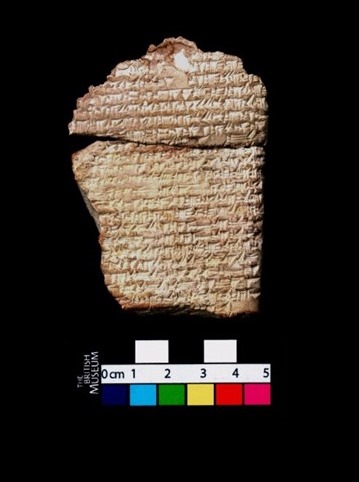

Myth of Adapa

One day when Adapa is out in his boat the South Wind rushes down and blows him toward shore, breaking his boat into pieces and throwing him into the sea. Enraged, Adapa lashes out and breaks the wings of the South Wind and then goes home. News of this soon reaches Anu, who summons Adapa to him to explain. There is no indication that Anu wishes to punish Adapa, but Enki, seeming to fear Anu's wrath, gives his son explicit instructions on how to behave when he reaches the heavens.

Enki tells him how to greet the gatekeepers, Tammuz and Gishida, what to say to them, and then goes on to warn Adapa against eating or drinking anything offered. Anu is angry, he says, and will offer the food of death and the water of death along with oil for anointing and a fresh robe; the oil and the robe should be accepted, but not the food and drink.

ANU'S BENEVOLENCE INFUSED THE OTHER GODS AS HE HIMSELF WITHDREW HIGHER AND HIGHER INTO THE HEAVENS. HE WAS FINALLY SEEN AS THE MASTER CREATOR BEHIND ALL THE WORKINGS OF THE UNIVERSE.

When Adapa appears at the gates, he greets Tammuz and Gishida as instructed, and they are impressed by him and recommend him highly to Anu. Since the first advice Enki gave has obviously proven useful, Adapa follows the rest. Anu listens to Adapa's explanation of the altercation with the South Wind and orders the Food of Life and the Water of Life be brought so that Adapa may become immortal. He does this because he is impressed by Adapa's wisdom and honesty and cannot understand why Enki would create such a being and not allow it to live forever. When Adapa refuses the food and drink, Anu is confused and asks why he is behaving so. The second tablet of the story is damaged toward the end and the third tablet is broken, but it seems as though Adapa tells Anu of the advice Enki gave him and that Anu becomes angry and punishes Enki.

It seems clear that Enki knew that Anu was going to offer Adapa eternal life and purposefully deceives him to prevent it.Although the text is damaged in the second tablet, there is evidence that this offer can only be made once, and when Adapa refuses the gift, he is given no second chance. The story is similar to the biblical tale of the Fall of Man in Genesis 3:22-23.Though it is not expressed directly in the myth, Enki's reasoning seems similar to Yahweh 's in the Genesis story where, after Adam and Eve are cursed for eating off the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, Yahweh casts them out before they can also eat off the Tree of Life:

Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil; and now, lest he put forth his hand and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live forever; Therefore the Lord God sent him forth from the garden of Eden .(Genesis 3:22-23)

Enki understands that human beings cannot be like the gods because that would upset the natural order. Adapa must remain mortal, must keep in his place, for creation to function as it should. In another story, The Atrahasis , it is established that humans are created with limited life spans by the will of the gods. In offering immortality to Adapa, Anu is upsetting the natural order, but he makes the offer because of his compassion; he feels it is a disservice to Adapa to have made him wise enough to recognize his mortality but unable to do anything to escape death. This compassion and understanding are characteristic of Anu as was seen in Enuma Elish when he tries to bring peace through diplomatic negotiation instead of continued war .

THE MOST HIGH GOD

Anu's benevolence infused the other gods as he himself withdrew higher and higher into the heavens. He was finally seen as the master creator behind all the workings of the universe but distanced from both humanity and the other gods. The only deity who had access to Anu was his son Enlil who gradually took on his father's characteristics and power. Even after Enlil became more popular, however, Anu continued to be venerated throughout the country. In the city of Uruk , where Inanna was the patron deity, Anu was honored by a large temple which continued in operation from c. 2000 BCE to c. 150 BCE and served as an astronomical observatory and library. A hymn to Anu from early in this period illustrates the high regard he was accorded.The hymn reads, in part:

O Prince of the gods, whose utterance ruleth over the obedient company of the gods; Lord of the horned crown, which is marvellously splendid; thou travellest hither and thither on the raging storm; thou standest in the royal chamber to be admired as a king.

At thy word the gods cast themselves on the ground in a body like a reed on the stream; they command blows like the wind and causes food and drink to thrive; at the word the angry gods turn bck to their habitations

May all the gods of heaven and earth appear before thee with gifts and offerings; may the kings of the countries bring to thee heavy tribute; may men stand before thee daily with sacrifices, prayers, and adorations.

To Uruk, thy city, do thou show abundant favor; O great god Anu, avenge thy city in hostile lands. (Wallis Budge, 106-107)

Even though he was eventually prayed to less and less directly, he was still considered the power behind the power of the gods. Offerings continued to be brought to his temple at Uruk long after he was no longer associated closely with the daily lives of the people. Scholar Stephen Bertman writes:

Anu was the august and revered "chairman of the board" of the Mesopotamian pantheon . His name literally meant "heaven". He was the supreme source of authority among the gods, and among men, upon whom he conferred kingship. As heaven's grand patriarch, he dispensed justice and controlled the laws known as the meh that governed the universe. (116)

When the Assyrian Empire fell in 612 BCE, many of the Mesopotamian gods associated with their rule were abandoned. The Assyrians had taken characteristics of many different gods for their own (the best example of this is their great god Assur/ Ashur ), and those who felt they had suffered under Assyrian rule vent their frustration and vengeance on Assyrian cities , temples, and the statues of the gods. Some gods continued to be acknowledged, however, and Anu was among these.Worship of Anu continued into the Hellenistic period of Mesopotamian history and, through his association with Marduk, on up to c. 141 BCE when the Parthians controlled the region.

Letters to the Dead in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

In the biblical Book of Luke, the story is told of Lazarus and the Rich Man in which a man of wealth and the poorest beggar both die on the same day. The beggar, Lazarus, finds himself in paradise while the rich man is in torment. He looks up to see Father Abraham with Lazarus beside him and asks if Lazarus might bring him some water, but this is denied; there is a great chasm fixed between those in heaven and those in hell, and none may cross. The rich man then asks if Abraham could send Lazarus back to the world of the living to warn his family because, he says, he has five brothers who are all living the same self-indulgent lifestyle he enjoyed and he does not want them to suffer the same fate. When Abraham answers, saying "They have Moses and the prophets; let them listen to them," the rich man responds that his brothers will not listen to scripture, but if someone should come back from the dead, they would surely listen to him. Abraham then says, "If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead" (Luke 16:19-31).

This story has been interpreted in many different ways over the centuries in order to make various theological points, but its theme is timeless: what happens after death? The rich man thought he was living a good life but finds himself in the worst kind of afterlife while Lazarus, who suffered on earth, is welcomed to a reward in heaven. The request of the rich man to send Lazarus back to earth sounds reasonable in that if someone came back from the dead to tell what it was like, people would certainly listen and live their lives differently; Abraham, however, denies the request.

Abraham's response, however disappointing it might seem to the rich man, is an accurate assessment of the situation. In the present day, people's stories of Near Death Experiences are accepted by those who already believe in that kind of afterlife and are denied by those who do not. Even if someone should come back from the dead, if one cannot accept that kind of reality, one will not believe their story and, in this same way, will certainly not accept ancient stories regarding the same kind of event.

Letter to the Dead

In ancient Egypt , however, the afterlife was a certainty throughout most of the civilization 's history. When one died, one's soul went on to another plane, leaving the body behind, and hoped for justification by the gods and an eternal life in paradise.There was no doubt that this afterlife existed, save during the period of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE), and even then the literature which expresses cynicism toward the next life could be interpreted as a literary device as easily as a serious theological challenge. The soul of a loved one did not cease to exist at death nor was there any danger of a surprise in the afterlife such as the rich man from Luke experiences.

An exception is in the fictional work from Roman Egypt (30 BCE - 646 CE) known as Setna II, which is the probable basis for the Luke tale. In one part of Setna II, Si-Osire leads his father Setna to the underworld and shows him how a rich man and a poor man experienced the afterlife. Contrary to Setna's earlier understanding that a wealthy man would be happier than the poor, the rich man suffers in the underworld and the poor man is elevated. Si-Osire leads his father to the afterlife to correct his misunderstanding, and their short trip there illustrates the closeness ancient Egyptians felt to the next world. The dead lived on and, if one wanted to, one could even communicate with them. These communications are known today as 'letters to the dead'.

THE EGYPTIAN AFTERLIFE & THE DEAD

It was believed that, after one died and the proper mortuary rituals had been observed, one passed on to judgment before Osiris and his tribunal, and if one had lived a good life, one was justified and passed on to paradise. The question of 'What is a good life?' was answered through the recitation of the Negative Confession before the tribunal of Osiris and the weighing of the heart in the balance against the white feather of truth, but even before one's death, one would have a fairly good idea of one's chances in the Hall of Truth.

The Egyptians did not rely on ancient texts to instruct them on moral behavior but on the principle of ma'at , harmony and balance, which encouraged them to live in peace with the earth and with their neighbors. Certainly, this principle was illustrated in religious stories, embodied in the goddess of the same name, invoked in written works such as medical texts and hymns, but it was a living concept which one could measure one's success in meeting daily. One would not need someone to come back from the dead with a warning; one's actions in life and their consequences would be enough - or should have been - to give a person a fairly good indication of what awaited them after death.

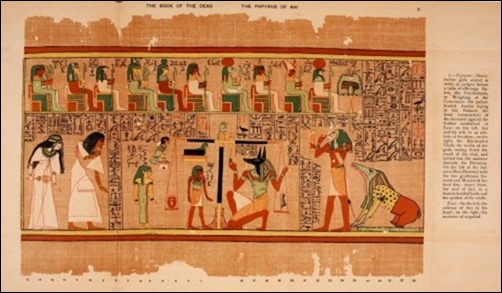

Papyrus of Ani

The justified dead, now in paradise, had the ear of the gods and could be persuaded to intercede on people's behalf in answering questions, predicting the future, or defending the petitioner against injustice. The gods had created a world of harmony, and all one needed to do in order to reach paradise in the next was to live a life worthy of eternity. If one made each day an exercise in creating a life one would wish to continue forever, founded on the concept of harmony and balance (which of course included consideration and kindness for one's neighbors), one could be confident of entry to paradise after death.

Still, there were supernatural forces at work in the universe which could cause one problems along life's path. Evil demons, angry gods, and the unhappy or vengeful spirits of the dead could all interfere with one's health and happiness at any time and for any reason. Simply because one was favored by a god, like Thoth , in one's life and career did not mean that another, like Set, could not bring one grief. Further, there were simply the natural difficulties of existence which troubled the soul and threw one off balance such as sickness, disappointment, heartbreak, and death of a loved one. When these kinds of troubles, or those more mysterious, came upon a person, there was something direct they could do about it: write a letter to the dead.

HISTORY & PURPOSE

Letters to the Dead date from the Old Kingdom (c. 2613 - 2181 BCE) through the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE), essentially the entirety of Egyptian history. When a tomb was constructed, depending upon one's wealth and status, an offerings chapel was also built so that the soul could receive food and drink offerings on a daily basis. The letters to the dead, often written on an offering bowl, would be delivered to these chapels along with the food and drink and would then be read by the soul of the departed. Egyptologist David P. Silverman notes how "In most cases, however, interaction between the living and the dead would have been more casual, with spoken prayers that have left no trace" (142). It is for this reason that so few letters to the dead exist today but, even so, enough do to understand their intent and importance.

One would write a letter in the same way one wrote to a person still living. Silverman explains:

Whether inscribed on pottery bowls, linen, or papyrus, these documents take the form of standard letters, with notations of addressee and sender and, depending upon the tone of the letter, a salutation: "A communication by Merirtyfy to Nebetiotef: How are you? Is the West taking care of you as you desire?" (142)

The 'west', of course, is a reference to the land of the dead, which was thought to be located in that direction. Osiris was known as the 'First of the Westerners' in his position as Lord of the Dead. As Silverman and others note, a response was expected to these letters since Spell 148 and Spell 190 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead enabled a spirit to let the living know how it was doing in the afterlife.

Osiris

Once salutations and pleasantries were expressed, the sender would get to the matter of the message and this was always a request for an intercession of some kind. Often, the writer reminds the recipient of some kindness they performed for them or the life they lived happily together on earth. Egyptologist Gay Robins cites one of these:

A man points out in a letter to his dead wife that he married her 'when I was a young man. I was with you when I was carrying out all sorts of offices. I was with you and I did not divorce you. I did not cause your heart to grieve.I did it when I was a youth and when I was carrying out all sorts of important offices for Pharaoh , life, propsperity, health, without divorcing you, saying "She has always been with me- so said I!"' In other words, as men climbed the bureaucratic ladder, it was probably not unknown for them to divorce the wives of their youth and remarry a woman more appropriate or advantageous to their higher rank. (63-64)

This husband reminds his wife of how faithful and dutiful he was to her prior to making his request for her help with his problem. Egyptologist Rosalie David notes how "requests found in the letters are varied: some sought help against dead or living enemies, particularly in family disputes; others asked for legal assistance in support of a petitioner who had to appear before the divine tribunal at the Day of Judgment; and some pleaded for special blessings or benefits" (282). The most often made requests, however, deal with fertility and birth through appeals for a healthy pregnancy and child, most often a son.

LETTERS & RESPONSES FROM THE DEAD

A writer would receive a response from the dead in a number of different ways. One could hear from the deceased in a dream, receive some message or 'sign' in the course of a day, consult a seer, or simply find one's problem suddenly resolved. The dead, after all, were in the company of the gods, and the gods were known to exist and, further, to mean only the best for human beings. There was no reason to doubt that one's request had been heard and that one would receive an answer.

Osiris was the lord of justice, and it only made sense that a soul in his presence would have greater influence than one still in the body on earth. Should this seem strange or 'archaic' to a modern-day reader, it should be remembered that there are many who observe this same belief today. The souls of the departed, especially those considered holy, are still thought to have more pull with the divine than someone on earth. Silverman comments:

In all cases, the deceased is urged to take action on behalf of the writer, often against malignant spirits who have afflicted the author and his or her family. Such requests frequently refer to the underworld court and the role of the deceased within it: "you must instigate litigation with him since you have witnesses at hand in the same cityof the dead". The principle is stated succinctly on a bowl in the Louvre in Paris : "As you were one who was excellent upon earth, so you are one who is in good standing in the necropolis". Despite this legalistic aspect, the letters are never formulaic but vary in content and length. (142)

Clearly, writing to someone in the afterlife was the same as writing to one in another city on earth. There is almost no difference between the two types of correspondence. A letter written in the 2nd century CE from a young woman named Sarapias to her father follows roughly the same model:

Sarapias to Ammonios, her father and lord, many greetings. I constantly pray that you are well and I make obeisance on your behalf before Philotera. I left Myos Hormos quickly after giving birth. I have taken nothing from Myos Hormos...Send me 1 small drinking cup and send your daughter a small pillow. (Bagnall & Cribiore, 166)

ONE WOULD WRITE A LETTER TO THE DEAD IN THE SAME WAY ONE WROTE TO A PERSON STILL LIVING.

The only difference between this letter and one a son writes to his deceased mother (c. First Intermediate Period of Egypt , 2181-2040 BCE) is that Sarapias asks for material objects to be sent while the son requests spiritual intervention. The son begins his letter with a similar salutation and then, just as Sarapias explains how she needs a cup and pillow sent, makes his request for aid. He also reminds his mother of how dutiful a son he was while she lived, writing, "You did say this to your son, 'Bring me quails that I may eat them', and this your son brought to you, seven quails, and you did eat them" (Robins, 107).Letters like this one also make clear to the deceased that the writer has not 'garbled a spell' in performing the necessary rituals. This would be most important in making sure that the soul of the deceased continued to be remembered so it could live well in the afterlife.

Once the soul had read the letter, the writer had only to be patient and wait for a response. If the writer had committed no sins and had performed all the rituals properly, they would receive a positive response in some fashion. After making their requests, the writers frequently promised gifts in return and assurances of good conduct. Robins comments on this:

In a First Intermediate Period letter to the dead, a husband tells his wife: 'I have not garbled a spell before you, while making your name to live upon the earth', and he promises to do more for her if she cures him of his illness: 'I shall lay down offerings for you when the sun's light has risen and I shall establish an altar for you'. The woman's brother also asks for help and he says, 'I have not garbled a spell before you; I have not taken offerings away from you'. (173)

Since the dead person retained their personal identity in the next world, one would write them using the same kinds of touches that had worked in life. If one had gotten their way through threats, then threats were used such as suggesting that, if one did not get one's wish, one would cut off offerings at the tomb. Offerings were made to the gods in their shrines and temples regularly, and the gods clearly heard and responded, and so it was thought the dead did the same. The problem with such threats would be that, if one stopped bringing offerings, one was more likely to be haunted by an angry spirit than have their request granted. Just as the gods frowned on petulant people's impiety in withholding offerings, so did the dead.

CONCLUSION

Every ancient culture had some concept regarding the afterlife, but Egypt's was the most comprehensive and certainly the most ideal. Egyptologist Jan Assman notes:

The widespread prejudice that theology is the exclusive achievement of biblical, if not Christian, religion is unfounded with regard to ancient Egypt. On the contrary, Egyptian theology is much more elaborate than anything that can be found in the Bible . (2)

The Egyptians left nothing to chance - as can be observed in the technical skill evident in the monuments and temples which still stand - and this was as true of their view of eternity as anything else. Every action in one's life had a consequence not only in the present but for eternity. Life on earth was only one part of an everlasting journey and one's behavior affected one's short-term and long-term future. One could feel assured of what awaited after life by measuring one's actions against the standard of harmonious existence and the example set by the gods and the natural world.

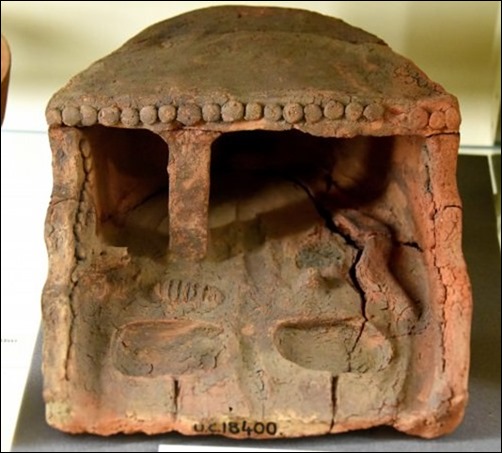

Egyptian Soul House

The Egyptian version of the story in Luke, though similar, is significantly different. The rich man in Setna II would expect to find punishment in the next life for ignoring the principle of ma'at . The beggar in the story would not have expected, nor been entitled to, a reward simply for suffering. Everyone suffered, after all, at one time or another, and the gods owed no one any special recognition for that.

In Setna II, the rich and poor man are punished and rewarded because their actions on earth either dishonored or honored ma'at, and, while others may have envied or pitied them, they could have expected what awaited them beyond death. In the Christianized version of Setna II which appears in Luke, neither the rich man nor Lazarus has any idea what is waiting for them. The Luke version of the story, in fact, would have probably been confusing to an ancient Egyptian who, if they had a question concerning the afterlife and what waited beyond, could simply write a letter and ask.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License