Aristophanes › Aristippus of Cyrene › The Mummy's Curse: Tutankhamun's Tomb » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Aristophanes › Who was

- Aristippus of Cyrene › Who was

- The Mummy's Curse: Tutankhamun's Tomb › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Aristophanes › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Aristophanes was the most famous writer of Old Comedy plays in ancient Greece and his surviving works are the only examples of that style. His innovative and sometimes rough comedy could also hide more sophisticated digs at the political elite and deal with social issues such as cultural change and the role of women in society. Indeed, the plays of Aristophanes are not only a record of Greek theatre but also provide an invaluable insight into many of the political and social aspects of ancient Greece, from the practicalities of jury service to details of religious rituals in major festivals.

LIFE & CHARACTER

Little is known about Aristophanes beyond what can be gleaned from his plays and a fictional portrait in Plato ’s Symposium .From the dates of his works we may surmise that he was born between 460 and 450 BCE and died sometime between 386 and 380 BCE. He was from Athens and he may have spent a period of his youth on Aegina following his father Philippus' move there. No contemporary physical portrait survives, but we may surmise from comments in some of his works that he was bald.

THE POET IS PRESENTED AS A RATHER AMIABLE CHAP, SOCIABLE, AND SOMEONE WHO 'DIVIDES HIS TIME BETWEEN APHRODITEAND DIONYSOS'.

Plato presents a fictional gathering of historical characters in his Symposium, but Aristophanes was still well known at the time of its creation (380s BCE) and, therefore, we may assume that the portrayal of Aristophanes reflected this fact and was recognisably accurate. The poet is presented as a rather amiable chap, sociable, and someone who 'divides his time between Aphrodite and Dionysos', ie likes women, boys, and wine. That Plato was favourably disposed to Aristophanes is evidenced in the positive tones of the epitaph he later wrote for the great poet. Plato did, however, in his Apology , blame the poet for fuelling a public distrust of Socrates .

ARISTOPHANES' PLAYS

More concrete are the works of Aristophanes. Although we know that he wrote more, eleven plays survive and they are the only examples of the so-called Old Comic style which gave way, in the 4th century BCE, to a newer, more sophisticated form of comic plays which focussed on intrigue and recurring characters. In contrast, the Old Comedies were by that time looked on as being rather vulgar and lacking in sophistication, Aristotle was one of their staunchest critics. However, it is these older comedies which have perhaps better stood the test of time and appear to the modern reader to be much more contemporary.

Aristophanes' surviving full plays are:

1. The Archarnians (425 BCE) about the formation of a peace treaty.

2. The Knights (424 BCE) an attack on Cleon.

3. The Clouds (423 BCE) criticising Socrates for corruption and sophistry.

4. The Wasps (422 BCE) poking fun at the Athenian jury system and the Athenians' preoccupation with litigation.

5. Peace (421 BCE) on the peace with Sparta .

6. The Birds (414 BCE) where birds construct a new city in the sky and better the gods.

7. Lysistrata (411 BCE) where women across Greece go on a sex strike to compel their men to make peace.

8. The Poet & The Women or Thesmophoriazusae (411 BCE) where women debate the elimination of Euripides

9. The Frogs (405 BCE) where Dionysos visits Hades and judges a poetry competition between Aeschylus and Euripedes.

10. The Ecclesiazusae (c. 392 BCE) where women take over Athens and make all property communal.

11. Plutus or Wealth (388 BCE) where the god of wealth regains his sight and no longer distributes riches at random.

We know of other titles which have not survived, for example, his first play The Banqueters (427 BCE), and we know that there were two final plays after Plutus which were a little more in line with the new style of comedy. Several of his plays were produced by Callistratus, others by Philonides or Aristophanes himself, and many won prizes at prestigious festivals such as the City Dionysia of Athens.

Theatre Parodoi, Epidaurus

Aristophanes was most probably instrumental in the evolution of the Greek comic theatre, for example, in the role of the chorus and the reduction in topical references. Using parody, puns, and bold and colourful language, he was able to convey the full spectrum of emotions and, through satire and ridiculous exaggeration, he poked fun at the more ridiculous facets of Greek city-life. Few public figures escaped his sharp wit, and politicians such as Kleon and fellow artists like Euripides were a favourite target as were, on occasion, the populace as a whole. The following selection of extracts illustrates the poet's sly wit:

Sosias:

Well, I'd no sooner fallen asleep than I saw a whole lot of sheep, and they were holding an assembly on the Pnyx: they all had little cloaks on, and they had staves in their hands; and these sheep were all listening to a harangue by a rapacious-looking creature with a figure like a whale and a voice like a scalded sow.

(41; Act One, Scene One, The Wasps)

A dig at democracy and the voters being easily swayed by a good speaker.

Leader:

It's very like the way we treat our money

The noble silver drachma, that of old

We were so proud of, and the recent gold ,

Coins that rang true, clean-stamped and worth their weight

Throughout the world, have ceased to circulate.

Instead the purses of Athenian shoppers

Are full of shoddy silver-plated coppers

(183; Act Two, Scene Two, The Frogs )

A comment on the State reducing the silver content of coinage to save money.

Chorus:

Well, you must admit it's true

that it's chiefly among you [men]

That gluttons, thieves, and criminals abound,

Have you heard of banditesses,

Let alone kidnapperesses?

Are there any female pirates to be found?

(128; Act One, Scene Two, The Poet & The Women )

On the virtue of women.

Hail high-priest of subtle bilge...You,

swaggering along the streets as your eye darts shifty glances,

barefoot, putting up with trouble, looking disdainfully, all for us

( Clouds 359-63)

A less than flattering portrait of Socrates.

Not all subjects could be given the comic treatment; for example, higher gods such as Zeus and Athena and certain aspects of Greek religion had to be given due respect and Aristophanes was once charged by the council of Athens when, in The Babylonians (426 BCE) and during wartime, he represented the Greek city-states as Babylonian slaves on a treadmill.Nevertheless, the plays of Aristophanes are indicative of the high degree of freedom of speech tolerated in 5th century BCE Athens.

Aristippus of Cyrene › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Aristippus of Cyrene (c. 435-356 BCE) was a hedonistic Greek philosopher who was one of Socrates ' students along with other pupils such as Plato , Xenophon , Antisthenes, and Phaedo. He was the first of Socrates' students to charge a fee for teaching and, since Socrates had charged nothing, this, and the accusation he had betrayed Socrates' philosophy , created a life-long friction between Aristippus and Socrates' other disciples. He believed and taught that the meaning of life was pleasure and that the pursuit of pleasure, therefore, was the noblest path one could dedicate oneself to. It is hard to understand, at first, how Aristippus could have been a student of Socrates, so different seem their philosophies. However, Aristippus' most famous phrase, “I possess, I am not possessed”, is quite in line with Socrates' own view of life as presented by Plato and Xenophon, the two primary sources on Socrates' life.

Plato presents Socrates as a man who often enjoyed drinking wine but who never got drunk, who attended parties but never had the money to host one himself, and who seems to have lived primarily - in his later years at least - on monetary gifts from friends and admirers. Xenophon does not contradict Plato on any of the above points. Although Socrates could in no way be considered a hedonist, it is fairly easy to see how a young disciple of his could come to the conclusion that enjoying those things money can buy, without becoming a slave to the money with which to buy such things, would seem a worthwhile philosophy. Further, Socrates' habit of drinking heavily, but never appearing drunk or trying to acquire more wine, would be in line with Aristippus' philosophy of possessing, or enjoying, something without being possessed by that thing.

ARISTIPPUS CLAIMED THAT THE HIGHEST TRUTH ONE COULD ATTAIN WAS THE RECOGNITION THAT PLEASURE WAS THE PURPOSE OF HUMAN EXISTENCE AND THE PURSUIT OF PLEASURE WAS THE MEANING OF LIFE.

While Socrates pursued truth and sought understanding, Aristippus simplified the teaching of his master by claiming the highest truth one could attain was the recognition that pleasure was the purpose of human existence and the pursuit of pleasure was the meaning of life. In this, and in his scorn for those who complicated matters by thinking too precisely on them, he would be a kindred spirit of the Chinese hedonist philosopher Yang Zhu (440-360 BCE) who claimed that concerns about "right" and "wrong" were a waste of time because there is no god, no afterlife, and no reward for suffering needlessly by denying oneself when one could as easily, and more sensibly, enjoy life in the present.

Plato's dialogue of the Phaedo describes the last day of Socrates' life when his disciples came to visit him in his prison cell in Athens and they had their final philosophical discussion. The dialogue begins with the Pythagorean philosopher Echecrates meeting Socrates' student Phaedo (who was there at the prison and present at Socrates' death) and asking him to tell of the experience in the jail on the last day. Phaedo lists those who were present and Echecrates asks, “But Aristippus and Cleombrotus, were they present?” To which Phaedo replies, “No. they were not. They were said to be in Aegina ”(59c). As the island of Aegina was known as a pleasure resort, Plato certainly knew what he was doing in placing the hedonistic philosopher there instead of in attendance in Socrates' last hours. Whether the Cleombrotus mentioned in Phaedo is the same man whom Callimachus says leaped to his death after reading Plato's description of the afterlife and the journey of the soul in the dialogue of the Phaedo is not known, but if Cleombrotus was with Aristippus on Aegina, it may safely be assumed they were not there engaged in philosophical discourse, as Plato would have defined it, but would have been pursuing pleasure. As Plato did not approve of Aristippus (as, it seems, he did not approve of most of Socrates' other disciples nor they of him) the line referencing Aristippus' preference of pleasure on Aegina to philosophical conversation in an Athenian jail cell would have been intended by Plato to show how shallow Aristippus and his philosophy was. The ancient writer Diogenes Laertius (3rd century CE) mentions Plato's jab against Aristippus in Plato's "Book on the Soul", as the Phaedo was called.

Even so, Aristippus, like Socrates, focused his attention on practical ethics; the question, "What is the Good?" was in the forefront of his belief system. The values humans term "good" or "evil" are reducible to pleasure and pain; self-gratification, then, is a great good while self-restraint, in the face of certain pleasure, would be bad. Still, Aristippus maintained that one should not allow oneself to be possessed by those things which bring pleasure. According to Diogenes Laertius, when Aristippus was criticized for keeping a very expensive mistress named Lais, he replied, “I have Lais, not she me.” There was nothing at all wrong, then, with enjoying whatever it was one wanted to enjoy, as long as one knew the ultimate value of that thing or person and did not confuse that value with one's own personal freedom. In Aristippus' view, one should never trade one's freedom for anything. Self-restraint and self-gratification, then, were of equal value in maintaining one's personal liberty while pursuing the Good in life: pleasure.

ARISTIPPUS AT COURT

Aristippus lived at the court of the tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse (432-367 BCE) or, perhaps, of his son Dionysius the Younger (397-343 BCE) where he was highly paid for his teaching and writing . When he first arrived at the palace, Dionysius asked him what he was doing there and, allegedly, he said, "When I wanted wisdom I went to Socrates; but now that I want money I have come to you." The uncertainty of which king Aristippus lived with is due to the primary sources referencing "Dionysius" without clarifying whether the father or the son, and as their personalities were similar, it could be either. Plato had attempted to turn Dionysius the Younger into his Philosopher King and failed and so, if Aristippus served that king, it would further explain Plato's enmity toward Aristippus (even though no further explanation is required than Aristippus' philosophy of pleasure).Diogenes Laertius tells us that

[Aristippus] was a man very quick at adapting himself to every kind of place, and time, and person, and he easily supported every change of fortune. For which reason he was in greater favour with Dionysius than any of the others, as he always made the best of existing circumstances. For he enjoyed what was before him pleasantly, and he did not toil to procure himself the enjoyment of what was not present (III).

His position at the court was essentially "wise man"' or "counselor" but, according to the ancient reports, he seems to have spent much of his time simply enjoying himself at the expense of Dionysius. Diogenes Laertius illustrates this, writing, "One day he asked Dionysius for some money, who said, 'But you told me that a wise man would never be in want,' 'Give me some,' Aristippus rejoined, 'and then we will discuss that point;' Dionysius gave him some, 'Now then,' said he, 'you see that I do not want money'." (IV). He apparently lived very luxuriously at the court where, among his students, he taught his daughter Arete about philosophical hedonism. She, in turn, passed his teaching down to her son, Aristippus-the-Younger (also known as Aristippus-the-mother-taught because he was raised by his mother alone), who formalized the teachings in his own writings.The teachings of Aristippus and his Cyrenaic School would later influence the thought of Epicurus and his philosophy regarding the primacy of pleasure in understanding the ultimate meaning in one's life.

ARISTIPPUS' WRITING & LATER LIFE

According to some ancient sources, Aristippus wrote many books while, according to others, none. The primary source of anecdotes concerning his life is Diogenes Laertius who has been criticized for not citing his sources but mentions Aristippus' written works in the same passage where he says he wrote nothing. One of the works attributed to him was On Ancient Luxury, no longer extant, which seems to have been a kind of scandal sheet detailing the less philosophical affairs and dalliances of Greek philosophers with young boys (and with particular attention paid to Plato). While it is entirely possible Aristippus could have written such a work, it does not seem consistent with his character. He routinely seems to have regarded himself superior to his contemporaries, especially to Socrates' other students, and it seems unlikely he would have expended the effort to write anything about them at all.

Aristippus lived into old age after a life of luxury and pleasure and retired to his hometown of Cyrene where he died. His daughter and grandson systematized his philosophy, and Aristippus the Younger is thought to have formally founded the Cyrenaic School of Philosophy (one of the earliest so-called Socratic schools originally founded by Aristippus himself) based on his grandfather's teachings.

The Mummy's Curse: Tutankhamun's Tomb › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Howard Carter's 1922 CE discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun was world-wide news but, following fast upon it, the story of the mummy's curse (also known as The Curse of the Pharaoh ) became even more popular and continues to be in the present day. Tombs, pharaohs, and mummies attracted significant attention before Carter's find but that was nowhere near the level of interest the public showed afterwards. The world's fascination with ancient Egyptian culture began with the earliest excavations and travelogues published in the 17th and 18th centuries CE but gained considerable momentum in the 19th after Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832 CE), building upon the work of Thomas Young (1773-1829 CE), deciphered ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics through the Rosetta Stone and published his findings in 1824 CE.

Seal of Tutankhamun's Tomb

Champollion opened the ancient world of Egypt to the modern world because, after his work, scholars could read the texts on the monuments and inscriptions, wrote on their discoveries, and peaked greater interest in the civilization . More and more expeditions were launched to discover ancient artifacts for museums and private collections. Mummies and exotic artifacts were shipped out of Egypt to all parts of the world. Some of these found a home in museums while others were used as coffee tables and conversation curios by the wealthy. This interest in all things Egyptian spilled over into popular culture and it was not long before the young film industry capitalized on it.

THE MUMMY FILMS

The first film dealing with the subject was Cleopatra 's Tomb in 1899 , produced and directed by George Melies. The film is now lost but, reportedly, told the story of Cleopatra's mummy which, after its accidental discovery, comes to life and terrorizes the living. In 1911 the Thanhouser Company released The Mummy which tells the story of the mummy of an Egyptian princess who is revived through charges of electrical current; the scientist who brings her back to life eventually calms, controls, and marries her.

AFTER 1922, THERE HAS HARDLY BEEN A POPULAR WORK OF FILM OR FICTION DEALING WITH EGYPTIAN MUMMIES WHICH DOES NOT RELY ON THE CURSE PLOT DEVICE TO SOME DEGREE.

These early films dealt with Egypt generally and the concept of mummies as a kind of zombie, an animated corpse, but one retaining the person's character and memory. There was no curse involved in these early films but, after 1922, there has hardly been a popular work of film or fiction dealing with Egyptian mummies which does not rely on that plot device to some degree.

The first film on the subject to be a major success was The Mummy (1932) released by Universal Pictures. In the 1932 film, Boris Karloff plays Imhotep , an ancient priest who was buried alive, as well as the resurrected Imhotep who goes by the name of Ardath Bey. Bey is trying to murder Helen Grosvenor (played by Zita Johann) who is the reincarnation of Imhotep's love-interest, Ankesenamun. In the end, Bey's plans to murder and then resurrect Helen as Ankesenamun are thwarted but, before that happens, an audience is made well aware of the curse attached to Egyptian mummies and the serious consequences of disturbing the dead.

This film's great box-office success guaranteed sequels which were produced throughout the 1940's ( The Mummy's Hand , The Mummy's Tomb , The Mummy's Ghost , and The Mummy's Curse , 1940-1944) spoofed in the 1950's ( Abbot and Costello Meet the Mummy , 1955), continued in the 1960's ( The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb in `64 and The Mummy's Shroud in `67), and on to the 1971 Blood From the Mummy's Tomb . The mummy horror genre was revived with the remake of The Mummy in 1999 which was a re-make of the 1932 film and just as popular. This film inspired the sequel The Mummy Returns in 2001 and the films on the Scorpion King (2002-2012) which were equally well received for the most part. The film Gods of Egypt (2016) shifted the focus from mummies to Egyptian gods but, according to reports, the latest mummy film to appear in June 2017 returns audiences to the plot of Melies' 1899 film.

THE TOMB & THE PRESS

Whether a specific curse is central to the plot of all of these films, the concept of the dark arts of the Egyptians and their ability to transcend death always is. There is no doubt that the Egyptians were interested in the world after death and made ample provision for their continued journey there but they were not interested in cursing or terrorizing future generations. The execration texts which are found inscribed on tombs are simple warnings against grave -robbers and supernatural threats of what will happen to those who disturb the dead; the abundant evidence of tombs looted over the past few thousand years show just how effective these threats were. None of these were able to protect the tomb of its owner as effectively as the one generated and proliferated by the press corps in the 1920's and none will ever be as famous.

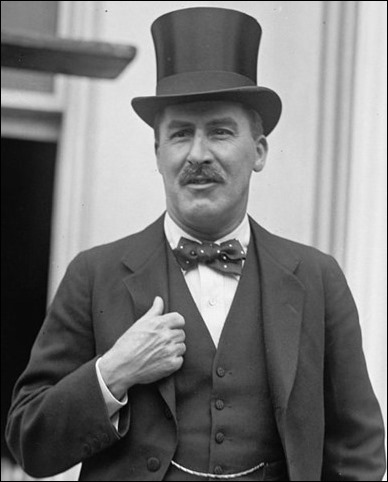

Howard Carter

Carter became a celebrity overnight when he discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun and, by his own admission, he did not appreciate it much at all. He writes:

Archaeology under the limelight is a new and rather bewildering experience for most of us. In the past we have gone about our business happily enough, intensely interested in it ourselves, but not expecting other folk to be more than tepidly polite about it, and now all of a sudden we find the world takes an interest in us, an interest so intense and so avid for details that special correspondents at large salaries have to be sent to interview us, report our every movement, and hide round corners to surprise a secret out of us. (Carter,63)

Carter had located the tomb in early November 1922 but needed to wait until his sponsor and financial backer, Lord Carnavon, arrived from England to open it. The tomb was opened by Carter, in the presence of Carnavon and his daughter Lady Evelyn on 26 November 1922 and, within a month, the site was attracting visitors from around the world and was already on itineraries for high-priced tours of Egypt.

The press descended on the tomb and its crew within a week and, since the tomb remained a high priority, would not leave.Further complicating the work of the excavation was the insistence of many of these visitors that they should have access to the tomb, guided tours, which caused disruptions in the daily schedule and started to seriously interfere with the scholarly identification and cataloging of the contents.

Antechamber of Tutankhamun's Tomb

Lord Carnavon was presented with another unexpected surprise. Although Carter believed Tutankhamun's tomb existed intact and could contain great riches, there was no way he could have predicted the incredible cache of treasures it held. When Carter first looked through the hole he made in the door, his only light a candle, Carnavon asked if he could see anything and he famously replied, "Yes, wonderful things" and would later remark that everywhere was the glint of gold (Carter, 35). The magnitude of the find and value of the artifacts precluded the authorities from allowing it to be divided between Egypt and Carnavon; the contents of the tomb belonged to the Egyptian government .

Carnavon, at least publicly, had no problem with this but needed not only a return on his investment but the necessary funds to continue to pay Carter and his team to clear and catalog the tomb's contents. He decided to solve his financial problems and the difficulties caused by the press in a single move: he sold exclusive rights to coverage of the tomb to the London Times for 5,000 English Pounds Sterling up front and 75% of the profits of world-wide sales of their articles to other outlets.

This decision enraged the press corps but was a great relief to Carter and his crew. Carter writes, "we in Egypt were delighted when we heard Lord Carnavon's decision to place the whole matter of publicity in the hands of The Times" (64). There would now be only a small contingent of press at the tomb at any given time instead of an army of them and the team could continue with the excavation without the former interruptions.

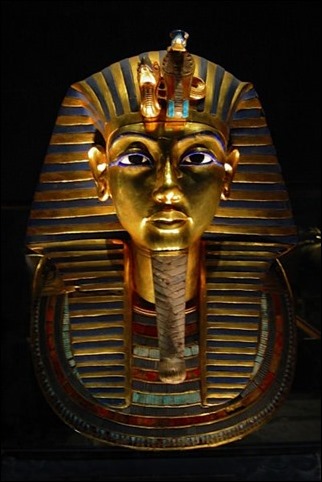

Death Mask of Tutankhamun

The news may have been welcomed by Carter and the others but not so warmly by the press corps. Many remained in Egypt hoping to get a scoop somehow or trying to find some other angle on the event they could exploit for a story; they did not have to wait very long. Lord Carnavon died in Cairo on 5 April 1923 - less than six months after the tomb was opened - and the mummy's curse was born.

THE CURSE OF TUTANKHAMUN

In March of 1923 the best-selling novelist and short story writer Marie Corelli (1855-1924 CE) sent a letter to New York Worldmagazine warning of dire consequences for anyone who disturbed an ancient tomb like Tutankhamun's. She "quoted" from an obscure book she claimed to own to support her claim. Since the publication of her first novel, A Romance of Two Worlds , in 1886 Corelli had been a celebrity and her letter was widely read. Her long-standing dislike for the press and for critics (who panned her books in spite of their popularity) added weight to the letter in that she must have felt her claim important enough to break with her custom of ignoring print publications. No one knows why Corelli sent the letter; she died the next year offering no explanation.

This letter, however, was gold for the media. It was used to support the claim that Carnavon was killed by a curse and Corelli's fame gave it weight in the popular imagination; but she was not the only "authority" on the subject cited by the media. In the United States, the newspaper The Austin American published an article on 9 April 1923 with the headline "Pharaoh Discoverer Killed By Old Curse?" which alludes to the Corelli letter but focuses on the testimony of one Miss Leyla Bakarat who, though having no training in Egyptology or history or curses, confirmed the truth behind Carnavon's death on the basis of her Egyptian heritage: Tutankhamun killed him with a curse through the bite of a spider.

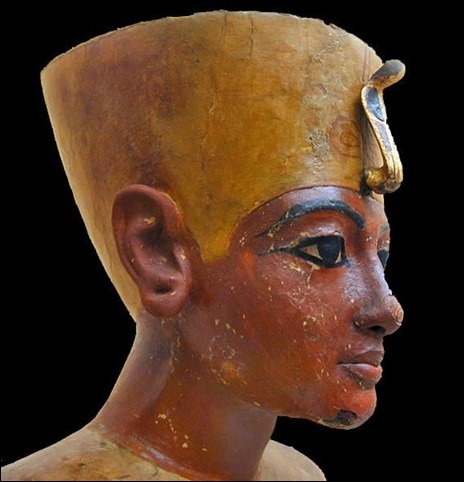

Tutankhamun

The Australian newspaper, The Argus , reported that Carnavon's death was caused by "the malign influence of the dead pharaoh" and quoted Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (famed as the creator of Sherlock Holmes) and a French spiritualist identified only as M. Lancelin for support. Conan Doyle was himself a spiritualist and a member of the Theosophical Society, as was Marie Corelli, and under other circumstances their religious views would have been handled by the mainstream press with considerably more skepticism. Since only the London Times had access to any news on developments at the tomb, however, other newspaper outlets had to make the most of whatever they had and so the mummy's curse blossomed in articles and editorials in newspapers around the world and those papers sold in record numbers. Egyptologist David P. Silverman describes the situation:

Some of the reporters had the aid of disgruntled Egyptologists, who had not only been denied access to the tomb, but also any information about it. Since there was no love lost between Carter and Carnavon and some of their scholarly colleagues, there was always someone who was willing to provide information about certain objects or inscriptions in the tomb, based solely on published photographs. In this manner, many inscriptions could be construed as curses by the public, especially after a "re-translation" by the press. For example, an innocuous text inscribed on mud plaster before the Anubis shrine in the Treasury stated: "I am the one who prevents the sand from blocking the secret chamber." In the newspaper, it metamorphized into: "...I will kill all of those who cross this threshold into the sacred precincts of the royal king who lives forever."

Such misrepresentation proliferated, and soon curses were being found in all of the inscriptions. Since few people could read the texts and thereby check the original, the reporters were safe. They could (and did) publish a photograph of the large golden shrine in the Burial Chamber, together with a "translation" of the accompanying inscription: "They who enter this sacred tomb shall swift be visited by wings of death." The carved figure of a winged goddess that accompanied the shrine would no doubt reinforce the "translated" threat. In reality, the texts on this shrine come from The Book of the Dead - a collection of spells intended to ensure eternal life, not shorten it! (Curse, 3)

Papers reported mysterious events surrounding Carnavon's death: the lights went out in Cairo when he died and, his son claimed, Carnavon's dog howled longingly when his master died and then fell over dead. Quite quickly, anyone who died who had any association with the tomb was linked to the curse. George Jay Gould I, who had visited the tomb, died a little over a month after Carnavon. In July of 1923 the Egyptian prince Bey was murdered by his wife in London and his death was also attributed to the curse. Carnavon's half-brother died in September of the same year and, though elderly and in poor health for some time, he was also a victim of the curse.

THE NON-CURSE & ITS LEGACY

Carnavon actually died of blood poisoning from a mosquito bite which became infected after he sliced it open while shaving.Although his son gave a detailed first-hand report of the howling dog's death, he was nowhere near the dog when it died but away in India . Whether the lights actually went out in Cairo when Carnavon died has never been confirmed but, if they did, it would have been nothing unusual since that was quite a common occurrence in the 1920's.

Howard Carter & Tutankhamun

The other deaths which have since been associated with the curse also have quite logical and natural explanations. The majority of those who participated in the opening and excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb lived for many years after.Egyptologist Arthur Mace, a member of Carter's crew, died in 1928 after a long illness but most went on to lead healthy, successful, and productive lives. Egyptologist Percy E. Newberry, who encouraged Carter to search for the tomb and was active in identifying and cataloging the contents, lived until 1949. Carnavon's daughter, who was present at the tomb's opening, lived until 1980. Carter himself, the man who first opened and entered the tomb and so would be considered the prime candidate to suffer from the curse, lived until 1939.

CARTER DID NOTHING TO PREVENT THE PRESS FROM CONTINUING TO DEVELOP THE CURSE STORY BECAUSE IT HAD THE MOST WONDERFUL EFFECT OF KEEPING THE PUBLIC AWAY FROM THE TOMB.

Carter never mentions the curse in his reports on the work of excavating the tomb but privately considered it nonsense. He did nothing to prevent the press from continuing to develop the story, however, because it had the most wonderful effect of keeping the public away from the tomb. Further, people who had taken artifacts from Egypt in the past for private collections were now sending them back or donating them to institutions because they feared the curse. Silverman notes how "nervous people began cleaning out their basements and attics and sending their Egyptian relics to museums in order to avoid being the next victim" (Curse, 3). Carter would work on the contents of the tomb of Tutankhamun for the next decade without the intrusions of the public or the press thanks to the mummy's curse.

However much good the curse may have done for Carter, and continues to do for the entertainment industry, it has had the unfortunate effect of obscuring the accomplishments of the pharaoh Tutankhamun (1336-c. 1327 BCE) which were quite significant. Tutankhamun's father was the famous "heretic king" Akhenaten (1353-c.1336 BCE) who abolished the traditional religious beliefs and practices of Egypt and instituted his own brand of monotheism. While many in the present day continue to admire Akhenaten as a "religious visionary" his actions were most likely prompted by the growing power, wealth, and prestige of the Cult of Amun and its priests which rivaled that of the king; his vision of a "one true god" effectively nullified the cult and diverted its wealth and property to the crown.

Tutankhamun reinstated the former religion - well over 2,000 years old at the time Akhenaten abolished it - and was working on other initiatives to repair the damage his father had done to Egypt's standing among foreign nations, its military, and its economy, when he died before the age of 20. It was left to the general Horemheb (1320-1292 BCE) to complete Tutankhamun's initiatives and restore Egypt to her former glory.

However intriguing the concept of an ancient Egyptian curse may be, there is no basis for it in reality. The tale of the curse took on a life of its own so that, now, people who know nothing of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb or the origin of the curse associate Egypt with mystical rites, an obsession with death, and curses. Public fascination with the mummy's curse has not lessened in the almost 100 years since it was created by the media and, since such stories and films continue to do well, it will most likely live on for centuries to come; it is hardly the legacy, however, that Tutankhamun would have chosen for himself.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License