Wall Reliefs: Apkallus of the North-West Palace at Nimrud › Amorite › Amphipolis » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Wall Reliefs: Apkallus of the North-West Palace at Nimrud › Origins

- Amorite › Origins

- Amphipolis › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Wall Reliefs: Apkallus of the North-West Palace at Nimrud › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin

Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions.It is the opium of the people.

(Karl Marx, Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right ).

When it comes to religion, many people who seek it out, even the most powerful ones, do so to cope with difficult times or events. The innate fragility of the human mind forces the human being to create the desire to find out who is behind anything, good or bad. The fear of the unknown future, the desire to achieve a complete state of health, security, and happiness, and the continuous attempt to counteract inevitable events, combine altogether to bring into existence the play of worshipping the superhuman controlling power.

I don't know how many people reading this article have seen an epileptic patient with seizures? I always ask my students what is the meaning of seizure? All of them, undoubtedly, replied correctly. Actually, the objective of the question was draw attention to the root of this word. In ancient times, sudden and generalized trembling movements were not considered a disease; that person was “seized” by an evil spirit for certain reason, people said. This concept has not changed since then, sad to say;many people still believe in this!

Apkallu & Lamassu Warding off Evil Spirits

This human-headed and winged Apkallu (left, together with the Lamassu on the right) guards and protects Room 6 on the ground floor of the British Museum. Alabaster bas-relief. Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Panel 2, originally from Room Z in the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

THE SAGES' STORY

The Mesopotamian literature about the concept of creation was very elaborate and this gave birth to the broad subject of Mesopotamian religion. Gods and goddesses communicated with humans via an intermediary. Accordingly, after the Earth and mankind were born, seven wise men or sages were created by the god Enki to establish culture and give civilization to mankind. Apart from being emissaries, those sages taught humans the moral code, arts, crafts, agriculture, copulation, etc. Some sages are said to have acted as advisors to some Sumerian kings before the Flood. The myths say their appearance was fish-like. Their precise names, general appearance, and “order” of creation by Enki is still a matter of debate, and of course, outside of the scope of this article.

THREE TYPES OF APKALLUS (HUMAN-HEADED, EAGLE OR BIRD-HEADED & FISH-LIKE) WERE PLACED AT DOORWAYS OR CORNERS OF THE NORTH-WEST PALACE; PEOPLE THOUGHT THAT EVIL SPIRITS LURKED HERE.

After the Flood, the sages' appearance changed. Humans and sages were capable of conjugal relationships; therefore, a new generation of sages (scholars suggested four in number) was created. Partially human and partially superhuman creature, the sage's role was mainly to be an adviser to Sumerian kings. The Epic of Gilgamesh tells that sages participated in the construction of the great walls of the city of Uruk in Southern Mesopotamia ; however, Gilgamesh's advisors were only human beings. This diversion from the usual norm at that time was striking.

These sages are depicted on a number of reliefs and are known as Apkallus (Apkallu is "sage" in Akkadian; they are known as Abgal in Sumerian). Three types of Apkallus (human-headed, eagle or bird-headed, and fish-like) were placed at doorways or room/hall corners of the North-West Palace. The installation was not haphazard; people thought that evil spirits lurked in doorways or corners. Sometimes, a group of Apkallu statuettes were buried beneath the floor. To augment this protection, colossal Lamassus (protective deities with human heads but winged lion/bull bodies) were also guarding doorways. Neo-Assyrian sculptors working between 911-612 BCE have left us an invaluable and priceless legacy of stone, documenting the shape and duty of Apkallus. Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 884-869 BCE), a harsh, merciless, and inexorable King, decorated the walls of his North-West Palace at the Assyrian capital of Nimrud with state-of-the-art, two-meter high alabaster bas-reliefs depicting a multitude of ritual, court, and vivid war scenes. Here, the innate habit struck and made an impact; even this stony-hearted and cold-blooded King looked for supernatural creatures to protect him and his palace against evil!

Room 7 ( Assyria, Nimrud) and to lesser extent Room 6, of the British Museum, houses the largest collection of these wallpanels of any museum, in an excellent state of preservation. I remember, the very first time I visited the British Museum, Irushed into Room 7, skipping everything else, to live the moment and enjoy the scent of my history!

Apkallu wearing a fish cloak

BASIC CHARACTERISTICS

Undoubtedly, visitors of the British Museum will be overwhelmed by the number and content of these wall panels. When you are in hurry and skimming them, you will think that the Apkallus are similar. In fact, no. There are many similarities and dissimilarities, but superficially, they look alike!

Supernatural creatures, winged genies, and protective spirits are the terms used to describe Apkallus. Even if they are of the same type (human or bird), they were sculpted differently. Their helmet or headdress, beard, hair, moustache, earring, necklace, dress, and other accessories are all different from each other, even their facial expression! Some are bare-footed and some wear sandals. “The Standard Inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II runs horizontally across all of the reliefs. When you see the images below, you will find out that the sculptors were very professional at placing and distributing the carved cuneiformsigns of the Standard Inscription text; this is one of my favourite skills of art!

IN GENERAL, THEIR BODY PARTS' ANATOMY& MUSCULATURE WERE EXAGGERATED; A BODYBUILDER'S PHYSIQUE.

Apkallus are winged. They can have a pair of wings or two pairs of wings (ie, two or four wings). Because they are depicted in profile, sometimes only three out of four wings appear; eagle-headed Apkallus usually demonstrate three wings on the reliefs.They either accompany Ashurnasirpal II (as well as his courtiers, attendants, and guards) in a ritual or court scene, or flank or face the so-called Sacred Tree or Tree of Life (a palm tree with palmette motifs) in the absence of the King. They usually stand; sometimes, they kneel at the Sacred Tree. The so-called South Suite of the Palace, which is believed to have been the King's private living area, is mostly devoid of any Apkallu (or even the King's images).

There are two outstanding wall reliefs depicting a different overall appearance. One is a human-headed Apkallus holding a goat with one hand and what appears to be (according to the British Museum) a large ear of corn in the other hand. The other Apkallu holds a deer and a palm branch. Here, I have a whole article dedicated to these Apkallus.

All of these slabs were unearthed by Sir Henry Layard during his work on the city of Nimrud during mid-19th century CE; they reached the British Museum after few years. Now enjoy the images!

THE APKALLUS' HEADS

The British Museum houses human-headed Apkallus (most are males, but there are females also), bird-headed (of an eagle), and what appears to human-shaped but fish-like or wearing a fish cloak. The latter's image can be seen above. In general, their body parts' anatomy and musculature were exaggerated; a bodybuilder's physique. All were depicted in profile.

Head of an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel at Door C (number 2), Room S, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Head of a winged protective spirit. This is an image of a “human adult male”. Note the terrorizing look. He wears a three-horned helmet or head cap and an earring. Note the fine and exquisitely carved details and compare them with the two images below. For example, the helmets, eyebrows, eyes, shape of the nose, the diameter of the curls of the beard, the wavy hair, and his facial expression.

Head of an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 6, Room G, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Head of a human-headed and winged protective spirit. He wears a two-horned (not three-horned) helmet. This spirit protects Ashurnasirpal II in a court ritual scene in Room G; this room was part of the so-called “East Suite”, where the King performed prayers and ceremonial rituals. Only high-ranking advisors and temple priests had access to this room. Compare this image's details with the above image. This spirit's facial expression is less hostile.

Head of a Male Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. This is a detail of Panel 1, which was lining door “a” of Room T, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Head of a human-headed and winged protective spirit. He does not wear a helmet; instead, he wears a diadem or a fillet with a rosette at the centre. The details of the diadem were very finely and beautifully carved. Each spirit wears a different type of earring; compare! Overall, his head seems to be rounded and “thick”; compare this with the image above, where the spirit's head appears a little bit elongated. This spirit was protecting the door of Room T; this was a small room, which was connected to Room S. Room S was the King's private area and part of the “South Suite” (most of the rooms in this private area did not contain Apkallus reliefs).

Head of a Female Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 20, Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Head of a human-headed and winged “female” protective spirit. She wears a two-horned helmet and an earring. Compare the shape of this helmet with the helmet of her male counterpart. This panel's spirit protects Room I. Room I was part of the L-shaped inner rooms of the East Suite; Room I was even more highly secured from divine and human intruders.

EAGLE-HEADED APKALLUS

Eagle-headed Apkallus are usually depicted beside the Sacred Tree; this might represent an additional fertilization function. A whole room, Room F of the Palace, was heavily lined and decorated with this kind of image.

Head of a Protective Spirit or Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel D1, Room G, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This is an eagle-headed protective spirit; a male, not a female. He does not wear a headdress; the feathers, which appear on his head, are part of his wing, behind the head and neck. Scrutinize each and every detail of this head; the peak, tongue, strange-looking eyebrow, small ear with feathers, feathers on the front of the neck, and the double-layered curls on the scalp hair. He does not wear an earring but wears a necklace with a pomegranate or a blossom at the front. Compare this eagle's image with the eagle below.

Head of a Protective Spirit or Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 3, Room F, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Another head of an eagle-headed and winged protective spirit. This spirit was in Room F. This room is adjacent to Room B (the Throne Room) and was entirely panelled by eagle-headed protective spirts and the so-called Sacred Tree or Tree of Life. This room was probably used by Ashurnasirpal II to rest after (or before) meeting with people in the adjacent throne room.

HAND-HELD ITEMS

What do their hands hold? This is different depending on the scene an Apkallu appears in. Options are a small bucket in the left and a pine cone in the right - the most common depiction; a chaplet in the left hand while the right hand is empty and raised; the left hand holding a flowering branch while the right is empty and raised; or, occasionally, the left hand may be holding a mace while the right hand is empty and raised. None of the Apkallus has two empty hands, and they don't hold swords or bows and arrows; instead, several types of daggers were tucked into their waistbands.

THE BANDUDDU OR BUCKET

The left hand may hold a small bucket ( banduddu in Akkadian) filled with fluid. Dr. Mouad Saed Al-Damirchi, former director general of the General Directorate of Antiquities in Iraq, once told me that this fluid might be water of melting snow; Assyrians thought that the snow on the mountains is scared as it comes from the sky (gods/goddesses). This, combined with a pine cone in the right hand, is the commonest depiction. Each Apkallu holds a different bucket from the others.

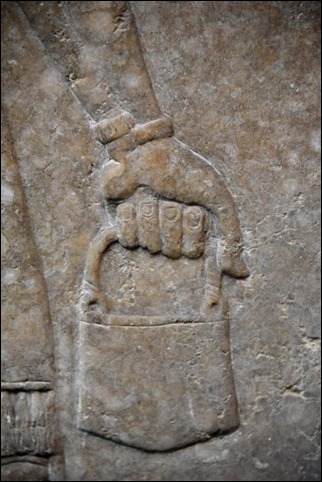

Bucket Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 2, Room G, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This bucket, filled with fluid, is held by the left hand of a human-headed protective spirit. The pail's ends are fixed into bird-shaped mounts. Note how the sculptor scratched the horizontal lines in order to carve “the Standard Inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II. The spirit's hand and bucket are covered with few cuneiform signs. Scrutinize well and compare these fine details with the those of the four examples below; all of these buckets are different from each other.

Bucket Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 6, Room G, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Just below the mid-part of the upper rim of this bucket, there is a winged disk, a symbol of the god Assur. The sculptor carved the cuneiform signs all over the fingers of the protective spirit's left hand and the bucket.

Bucket Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 23, Room B, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This is the left hand of a human-headed protective spirit, who stands behind Ashurnasirpal II (not shown here) holding a bucket.

Bucket Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of a panel lining Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The left hand of an eagle-headed protective spirit holds a bucket. Note the absence of cuneiform signs in this panel, because the “Standard Inscription” was carved above the panel.

Bucket Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of a panel from Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

An eagle-headed protective spirit holds a bucket, devoid of cuneiform signs. Note that the bottom of the bucket is not flat.

THE PINE CONE

When the left hand holds a bucket, the right hand usually holds what appears to be a pine cone ( mullilu in Akkadian). The Apkallu dips the cone into the bucket and sprinkles the King (and the people around him) with that fluid in ritual ceremonies to purify them.

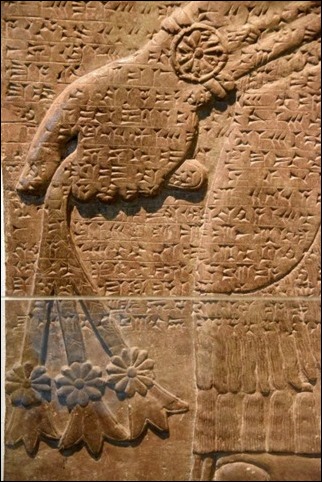

Pine Cone Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 4, Room F, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The right hand of an eagle-headed protective spirit holds a pine cone and sprinkles fluid on the back of the head of the King (left lower part of the image represents the King's hair).

Pine Cone Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 4, Room G, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The right hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a pine cone and sprinkles fluid on the back of the head of a royal attendant; the tip of the cone lies in front of the string of the bow held by that attendant.

THE CHAPLETS

It also occurs that the left hand holds a chaplet while the right hand is empty but raised (the fingers are extended and held together) so that the right palm faces the viewer. This can be seen with female human-headed Apkallus flanking the Sacred Tree, not the King. This gesture suggests that the Apkallu is performing an act of worship or prayer.

Chaplet Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 20, Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The left hand of a human-headed female protective spirit holds what appears to be a string with beads or chaplet; she seems to perform an act of worship or counting prayers. Cuneiform signs were carved on the surface of the hand and fingers but only on one bead of the chaplet. The right hand (not shown) is raised and holds nothing.

Apkallu Chaplet

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 16, Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The left hand of a human-headed female protective spirt holds a chaplet. There are no cuneiform signs.

THE FLOWERING BRANCHES

Another possible depiction is the left hand holding a flowering branch while the right hand is empty and raised. Once again, these branches are used in religious ceremonies and during the act of worship. Needless to say, the shape of the flowering branch is different.

Flowering Branch Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 2, Room Z (this is a corridor between the South Suite and West suite), the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The left hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a flowering branch with blossoms while performing an act of worship.There are no cuneiform signs.

Flowering Branch Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel at Door C (number 2), Room S, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The left hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a flowering branch. Note the placement and distribution of the cuneiform signs.

Flowering Branch Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 8, Room Z, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq. An interesting fact to mention is that other parts of this panel are currently housed in the Prince of Wales Museum, Iraq, and Bombay!

The left hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a flowering branch. Note the absence of inscriptions.

Flowering Branch Held by an Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 1, Door A, Room F, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The left hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a flowering branch. There are no cuneiform signs.

THE MACE

Lastly, the left hand can also sometimes be seen holding a mace (a symbol of authority) while the right hand is empty and raised. This scene is visible in the depiction of an Apkallu guarding a doorway into the Throne Room.

Apkallu Mace

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 26, Room B (Throne Room), the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The left hand of a human-headed spirit holds a mace; the right hand is raised and does not hold anything.

THE APKALLU'S EMPTY HANDS

Apkallu's Hand

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 1, Door A, Room F, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The right hand of a human-headed protective spirit; the palm faces the viewer and there are typical human palm creases. He wears two bracelets.

Hand of Apkallu

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 26, Room B (Throne Room), the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The raised right hand of a human-headed protective spirit. Note the absence of palm creases and the bracelet with a rosette.

THE APKALLUS' DAGGERS

Apkallu's Daggers

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel D1, Room G, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Two daggers within their sheaths are carried by an eagle-headed protective spirit. They are tucked into his waistband. Note the overlying carved decorative motifs.

Apkallu's Daggers

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 16, Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Two daggers were tucked into the waistband of a human-headed female protective spirit. There are no overlying decorative motifs.

Apkallu's Daggers

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel at Door C (number 2), Room S, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

One of the handles of these three daggers is shaped like what looks like it could be a ram's head. The daggers were inserted into the waistband of a human-headed protective spirit.

Apkallu's Daggers

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE Detail of Panel 2, Room Z (this is a corridor between the South Suite and West suite), the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Another human-headed protective spirit carries three daggers; one of the handles of these three daggers appears to be in the shape of a ram's head. The daggers are tucked into the waistband.

COMPLETE PANELS

Female Apkallus Flanking the Scared Tree

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Panel 16, Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This panel depicts a pair of human-headed and winged female protective spirits flanking the so-called “Sacred Tree or Tree of Life”, and performing an act of worship. Note what they wear, hold, and do. Two wings appear only, for each one; compare this with the two images below.

Eagle-Headed Apkallus Flanking the Sacred Tree

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This complete panel shows a pair of eagle-headed and winged protective spirits flanking the so-called “Sacred Tree or Tree of Life”, and performing an act of worship. The Assyrian sculptor depicts eagle-headed spirits having three wings while the human-headed spirits display two or four wings.

Apkallu with Four Wings

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Panel 26, Room B, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This human-headed protective spirit has four wings. He guarded one of the entrances to the King's Throne Room.

When you visit the British Museum, spend some time focusing on these wonderful details. I hope in writing this article, I have drawn our readership's attention to this Assyrian art and mythology ’s details. I couldn't and I cannot include all zoomed-in images of all panels I have; instead, I have chosen a few examples to demonstrate.

This article was written in memory of Sir Henry Layard (1817-1894).

Archaeology holds all the keys to understanding who we are and where we come from.

(Sarah Parcak).

Amorite › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

The Amorites were a Semitic people who seem to have emerged from western Mesopotamia (modern day Syria ) at some point prior to the 3rd millennium BCE. In Sumerian they were known as the Martu or the Tidnum (in the Ur III Period), in Akkadian by the name of Amurru, and in Egypt as Amar, all of which mean 'westerners' or 'those of the west', as does the Hebrew name Amorite. They worshipped their own pantheon of gods with a chief deity named Amurru (also known as Belu Sadi - 'Lord of the Mountains' whose wife, Belit-Seri was 'Lady of the Desert'), which also became a designation for the people as the Akkadians also referred to them as 'the people of Amurru' and to the region of Syria as 'Amurru'. There is no record of what the Amorites called themselves. The god Amurru's association with the mountains and his wife's with the desert suggests that they may have originated in the area of Syria around Mount Hermon but this is unsubstantiated. Their origins are unknown and their precise history, until they settle in cities like Mari, Ebla, and Babylon, is equally mysterious. From their first appearance in the historical record, the Amorites had a profound impact on the history of Mesopotamia and are probably best known for their kingdom of Babylonia under the Amorite king Hammurabi. The span between 2000-1600 BCE in Mesopotamia is known as the Amorite Period, during which their impact on the region can most clearly be discerned, but there is no doubt that they influenced the people of the various cities long before that time and their impact was felt long after.

AMORITE MAY NOT HAVE ORIGINIALLY REFERRED TO A SPECIFIC ETHNIC GROUP BUT TO ANY NOMADIC PEOPLE WHO THREATENED THE STABILITY OF ESTABLISHED COMMUNITIES

EARLY HISTORY

The Amorites first appear in history as nomads who regularly made incursions from the west into established territories and kingdoms. The historian Marc Van de Mieroop writes:

The Amorites were semi-nomadic groups from northern Syria, whom Babylonian literature described in extremely negative terms:

The Amorite, he is dressed in sheep's skins;

He lives in tents in wind and rain;

He doesn't offer sacrifices.

Armed vagabond in the steppe,

He digs up truffles and is restless.

He eats raw meat,

Lives his life without a home,

And, when he dies, he is not buried according to proper rituals (83).

Van de Mieroop and others point out that 'Amorite' may not have originally referred to a specific ethnic group but to any nomadic people who threatened the stability of established communities. Even if this is so, at some point, 'Amorite' came to designate a certain tribe of people with a specific culture based on a nomadic lifestyle of living off the land and taking what was needed from the communities they encountered. They grew more powerful as they acquired more land until finally they directly threatened the stability of those in the established cities of the region.

This situation came to crisis during the latter part of the Ur III Period (also known as the Sumerian Renaissance, 2047-1750 BCE), when King Shulgi of the Sumerian city of Ur constructed a wall 155 miles (250 kilometres) long specifically to keep the Amorites out of Sumer. The wall was too long to be properly manned, however, and also presented the problem of not being anchored at either end to any kind of obstacle; an invading force could simply walk around the wall to bypass it and that seems to be precisely what the Amorites did. Amorite incursions led to the weakening of Ur and Sumer as a whole, which encouraged the region of Elam to mount an invasion and break through the wall. The sack of Ur by the Elamites in 1750 BCE ended Sumerian civilization, but this was made possible by the earlier incursions of the Amorites and their migrations throughout the region which undermined the stability and trade of the cities.

THE AMORITES & THE HEBREWS

At this point in history, according to some scholars, the Amorites play a pivotal role in the development of world culture. The biblical Book of Genesis states that the patriarch Terah took his son Abram (later Abraham), daughter-in-law Sarai, and Lot the son of Haran from Ur to dwell in the land of Haran (11:31). The historian Kriwaczek writes:

Terah's family were not Sumerian. They have long been identified with the very people, the Amurru or Amorites, whom Mesopotamian tradition blamed for Ur's downfall. William Hallo, Professor of Assyriology at Yale University, confirms that `growing linguistic evidence based chiefly on the recorded personal names of persons identified as Amorites…shows that the new group spoke a variety of Semitic ancestral to later Hebrew, Aramaic and Phoenician.' What is more, as depicted in the Bible, the details of the patriarch's tribal organization, naming conventions, family structure, customs of inheritance and land tenure, genealogical schemes, and other vestiges of nomadic life are too close to the more laconic evidence of the cuneiform records to be dismissed out of hand as late fabrications (163-164).

The Amorites of the Bible are depicted as pre-Israelite inhabitants of the land of Canaan and clearly separate from the Israelites. In the Book of Deuteronomy they are described as the last remnants of the giants who once lived on earth (3:11), and in the Book of Joshua they are the enemies of the Israelites who are destroyed by General Joshua (10:10, 11:8). If modern-day scholarship is accurate about the patriarchs of Israel descending from the Amorites, then there must have been some reason why the Hebrew scribes went to so much trouble to separate their own identity from that of the Amorites. It is thought that Terah, in taking his family from Sumer, retained the tribe's original ethnic identity and brought that cultural heritage with him to Canaan where Abraham, then Isaac, and then Jacob would establish that culture as `the children of Israel' (Jacob's name). The Book of Genesis tells the story of Joseph, Jacob's youngest son, and his sojourn in Egypt and rise to power there, and the Book of Exodus relates how the Hebrews were later enslaved by the Egyptians and were led from captivity to freedom back in Canaan by Moses. These biblical narratives would have served to separate the Israelites' national identity from their actual ancestors by creating new histories that highlighted their uniqueness among the people of the world. Kriwaczek notes that,

only by leaving Ur would Terah and his little family keep their Amorite identity and their Amorite way of life which was so important to subsequent Hebrew history. Had Terah stayed in Sumer, Abram would have shared in a very different destiny…The Amorites would never leave. They would eventually merge into the general population so thoroughly that after a few decades it would be impossible to distinguish them from their predecessors (165).

The fact that the events related in the Book of Exodus are not substantiated in any other ancient work, or by archaeological evidence of any kind whatsoever, supports the theory that the Hebrew writers of that book created a new narrative to explain their presence in Canaan, one without any connection to the Amorites of Mesopotamia. Throughout the early books of the Old Testament, the Amorites are repeatedly referred to negatively, except for a passage frequently cited from I Samuel 7:14 where some scholars claim that it is written that there was peace between the Amorites and the Children of Israel. But that passage actually says there was peace between the Philistines and the Israelites and does not mention the Amorites at all. This interpretation of the passage comes from the understanding that 'Amorite' had again come to refer to any nomadic people who interfered with established communities. While this may be true, it seems that 'Amorite' was even used to reference the early people of the land of Canaan which, according to the Book of Joshua, the Israelites conquered. In virtually every reference, then, the Amorites were considered `the other' by the Hebrew scribes, and this tradition continued for centuries down to the creation of the Talmud in which Jews are prohibited from engaging in Amorite practices. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia:

To the apocryphal writers of the first and second pre-Christian century [the Amorites] are the main representatives of heathen superstition, loathed as idolaters, in whose ordinances Israelites may not walk (Lev. xviii. 3). A special section of the Talmud (Tosef., Shab. vi.-vii. [vii.-viii.]; Bab. Shab. 67a et seq.) is devoted to the various superstitions called "The Ways of the Amorites." According to the Book of Jubilees (xxix. [9] 11), "the former terrible giants, the Rephaim, gave way to the Amorites, an evil and sinful people whose wickedness surpasses that of any other, and whose life will be cut short on earth." In the Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch (lx.) they are symbolized by "black water" on account of "their black art, their witchcraft and impure mysteries, by which they contaminated Israel in the time of the Judges".

The theory that the Amorites, through their appropriation and transmission of Mesopotamian myths, would produce the biblical narratives of the Old Testament, has been challenged repeatedly over the years and, no doubt, will continue to be. There seems to be more evidence to support this theory, however, than disprove it.

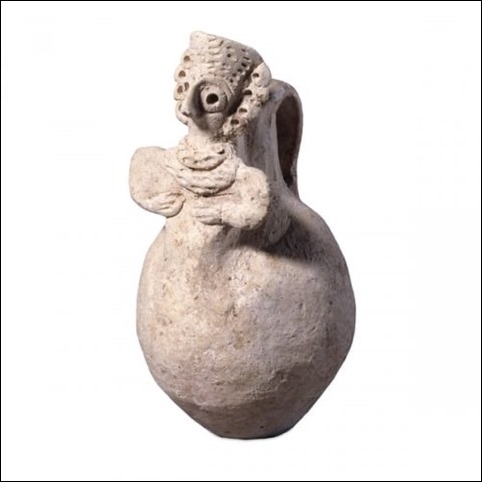

Amorite pottery juglet

THE AMORITE PERIOD IN MESOPOTAMIA

Following the sack of Ur in 1750 BCE, the Amorites merged with the Sumerian population in southern Mesopotamia. They had already been established in the cities of Mari and Ebla in Syria since 1900 BCE (Mari) and 1800 BCE (Ebla), and had ruled in Babylon since c. 1984 BCE. The Amorite king Sin-Muballit had assumed the throne in Babylon in 1812 BCE and ruled until 1793 BCE when he abdicated. He was succeeded by his son Ammurapi who is better known by his Akkadian name Hammurabi (reigned 1792-1750 BCE). The fact that an Amorite king ruled in Babylon prior to the fall of Ur supports the claim that not all 'Amorites' were Amorites and that, as previously mentioned, the term was used rather loosely to refer to any nomadic tribe in the Near East. The Amorites of Babylon seem to have been regarded positively in the region, while the roaming Amorites continued to be a source of instability. The Amorites of Babylon, just as those who inhabited other cities, worshipped Sumerian gods and wrote down Sumerian myths and legends. Hammurabi expanded the old city of Babylon and engaged in a number of successful military campaigns (one being the destruction of rival city Mari in 1761 BCE) that brought the vast region of Mesopotamia from Mari to Ur under Babylon's rule and established the city as the center of Babylonia (an area of land corresponding to modern-day Syria to the Persian Gulf). Hammurabi's military, diplomatic, and, political skills served to make Babylon the largest city in the world at the time and the most powerful. He was unable, however, to pass these talents on to his son and, after his death, the kingdom he had built began to fall apart.

Hammurabi's son, Samsu-Iluna (reigned 1749-1712 BCE) could not continue the policies his father had enacted nor defend the empire against invading forces such as the Hittites and Assyrians. The Assyrians were the first to make incursions and allowed for regions south of Babylon to break away from the empire easily. Hammurabi's conquest of Eshnunna in the north-east had removed a buffer zone and placed the border in direct contact with tribes such as the Kassites. The greatest blow came in 1595 BCE when Mursilli I of the Hittites (1620-1590 BCE) sacked Babylon and carried away the treasures of the city's temples and scattered the population (as he had done five years earlier, in 1600 BCE, at Ebla). The Kassites followed the Hittites in taking Babylon and re-naming it and they, in turn, were followed by the Assyrians. The Amorite Period in Mesopotamia was ended by 1600 BCE, though it is clear through the distinctive Semitic names of individuals on record that Amorites continued to live in the area as part of the general population. Amorites continued to pose problems for the Neo-Assyrian Empire as late as c. 900-800 BCE. Who these 'Amorites' were, and whether they were culturally Amorite, is unclear.In time, the cultural Amorites came to be referred to as 'Aramaeans' and the land they came from as Aram, possibly from the old designation of Eber Nari. Following the decline of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in c. 600 BCE, Amorites no longer appear under the name 'Amorite' in the historical record.

Amphipolis › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Amphipolis, located on a plain in northern Macedonia near Mt. Pangaion and the river Strymon, was an Athenian colony founded c. 437 BCE on the older Thracian site of Ennea Hodoi. Thucydides relates that the Athenian general Hagnon so named the town because the Strymon surrounds the site on three sides ("amphi" means "on both sides") and also relates that he built a fortification wall on its unprotected side. The city and its sea port, Eion, prospered due to its favourable geographic location and the proximity of abundant natural resources, especially gold, silver, and timber. In 2012 CE an impressive Hellenistic tomb was discovered, one of the most important archaeological finds of the last 40 years which has, once more, put Amphipolis in the lime-light.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The Spartan general Brasidas conquered the city in 424 BCE and defeated Kleon when Athens attempted to re-take Amphipolis two years later. In the latter battle Brasidas had brilliantly employed his peltasts to defeat the larger Athenian hoplite army, but the Spartan leader himself eventually succumbed to his wounds. The great military commander was buried in the city's agora and honoured with annual games. Amphipolis came back under Athenian control following the Peace of Nikias in 421 BCE; however, the Amphipolitans, in the event, opted to remain an independent polis ( city-state ) and in 367 CE made an alliance with the Chalkidian League. In 364 BCE the Athenians, still as eager as ever to guarantee their grain supply from the Black Sea, once more tried to make themselves masters of strategically important Amphipolis, this time led by the general Timotheos and with the initial encouragement of the Macedonian king Perdikkas III, who ruled Amphipolis at that time. Unwilling in the end to hand over the city, Perdikkas established a garrison there and, on his death, Macedonian control fell to his successor, Philip II.

PROBABLY A MACEDONIAN ADMINISTRATIVE CAPITAL, THE CITY WAS ALSO THE SITE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT MACEDONIAN MINT.

Although now a Macedonian city, Amphipolis did retain some degree of independence and many of her political institutions such as a demos or popular assembly, remained intact. Over time, as more and more Macedonian colonists settled in the polis, Philip, and later his son Alexander the Great, used Amphipolis as a base from which to attack Thrace and Asia. Probably a Macedonian administrative capital, the city was also the site of the most important Macedonian mint where, amongst others, the famous gold staters were produced. The site has also been a source of documentation regarding Macedonian military regulations. We are informed that soldiers who displayed great courage on the battlefield should be given a double share of the booty, that a general should ensure his army does not devastate a defeated territory by burning corn or destroying vines, and that soldiers must have their equipment in order, not sleep on guard duty, and report such failures amongst their comrades to their superior. Transgressors could be fined and those who reported them received a bonus.

Macedonian Gold Stater

When Rome conquered Macedon in 168 BCE, Amphipolis retained some importance as one of the four regional capitals. The city was an important stopping point on the via Egnatia highway which connected Greece to Asia. The city acquired impressive fortifications, especially around the ancient acropolis, measuring over 7,000 metres long and over 7 metres high in places. Augustus conferred the status of civitas libera, making it a free city and the emperor was even given the title of Ktistes or founder. In later times, from c. 500 CE, Amphipolis became the seat of an episcopal see and no fewer than four basilicas attest to the religious importance of the site in Late Antiquity. The site was abandoned in the 8th and 9th centuries CE following the Slavic invasions after which citizens of Amphipolis relocated to nearby Eion which survived into the Byzantine period. Amphipolis was again settled in the 13th to 14th centuries CE, from which period the remains of two towers survive.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS

Excavations of Roman Amphipolis have revealed traces of all the impressive architecture one would expect from a thriving Roman city. A bridge, gymnasium, public and private monuments, sanctuaries, and cemeteries all attest to the city's prosperity. From the early Christian period (after 500 CE) there are traces of four basilicas, a large rectangular building which may have been a bishop's residence, and a church.

Fortifications of Amphipolis

Basilica A was a three-aisled basilica with two floors and two rows of ten columns down its length. It was constructed on the site of a Roman bath. Parts of the marble flooring, some polychrome mosaics of wildlife, pieces of a hexagonal platform, and two rows of seats of the synthronon survive. Basilica B originally measured 16.45 x 41.6 metres and it too had marble decoration and mosaics. Basilica C dates to the second half of the 5th century CE and had two interior colonnades of six columns, of which the bases survive, as do mosaics of various geometric and wildlife designs. Basilica D is contemporary with Basilica C and had a marble and brick flooring; 15 column bases and various mosaics also survive.

The large rectangular structure which may have served as an episcopal palace measured over 48 metres wide and had walls 1.3 metres thick. Three cisterns in the southwest corner constructed using waterproof cement survive. Another building of interest is the early Christian church which included a large hexagonal chamber surrounded by a circular wall. The 6th century CE church had two floors with colonnades and much of the interior was tiled with marble, including the mosaic -tile flooring.Finally, two Byzantine towers either side of the Strymon River survive. The best preserved is the north tower which was built in 1367 CE and which stands 10 metres tall and originally had three stories. Both towers offered some protection to the nearby monastery on Mt. Athos.

Persephone Mosaic, Amphipolis

THE AMPHIPOLIS TOMB

The 4th century BCE burial mound at Amphipolis was discovered in 2012 CE and it is one of the most important archaeological finds of the last 40 years. It has a surrounding wall measuring almost 500 metres in circumference and constitutes the largest burial site ever found in Greece. The scale and impressive architecture of the tomb, which uses marble imported from Thassos, suggest the occupant was a person of great importance. An almost intact skeleton has been discovered within a wooden coffin placed in a limestone tomb in the third chamber of the complex. The chief archaeologist at the site, Katerina Peristeri, stated that the tomb dated to after the death of Alexander the Great (323 BCE) and, "in all probability belongs to a male and a general". Artefacts from the complex include a large stone lion (discovered in 1912 CE but now thought to have once stood atop the mound), two caryatids, two sphinxes, and a large pebble mosaic measuring 4.5 by 3 metres which depicts the god Hades abducting Persephone in a chariot led by Hermes. Historici en liefhebbers reikhalzend uit naar de resultaten van het lopende onderzoek naar de Amphipolis graf en om te ontdekken die werd begraven in zo'n prachtige graf.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License