Social Structure in Ancient Egypt › Amenhotep III › Ammon » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Social Structure in Ancient Egypt › Origins

- Amenhotep III › Who was

- Ammon › Who was

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Social Structure in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

The society of ancient Egypt was strictly divided into a hierarchy with the king at the top and then his vizier, the members of his court, priests and scribes, regional governors (eventually called 'nomarchs'), the generals of the military (after the period of the New Kingdom, c. 1570- c. 1069 BCE), artists and craftspeople, government overseers of worksites (supervisors), the peasant farmers, and slaves.

Social mobility was not encouraged, nor was it observed for most of Egypt's history, as it was thought that the gods had decreed the most perfect social order which was in keeping with the central value of the culture, ma'at (harmony and balance).Ma'at was the universal law which allowed the world to function as it should and the social hierarchy of ancient Egypt was thought to reflect this principle.

The people believed the gods had given them everything they needed, and set them in the most perfect land on earth, and had then placed the king over them as an intermediary between the mortal and divine realms. The primary responsibility of the ruler was to keep ma'at and, when this was accomplished, all the other obligations of his office would fall naturally into place.

Egyptian Workers

An Egyptian monarch could not personally oversee every aspect of the society, however, and so the position of the vizier was created as far back as the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150- c. 2613 BCE). The vizier (a sort of prime minister) delegated responsibilities to other members of the court, sending messages through scribes, and also oversaw the military and the operations of regional governors, public works projects, and tax collections among his many other duties.

At the bottom rung of this hierarchy were the slaves (people who could not pay their debts, criminals, or those taken in wars) and, just above them, the peasant farmers who made up 80% of the population and provided the resources which allowed the civilization to survive and flourish for over 3,000 years.

THE RISE OF THE GODS & THE CITIES

THE PEOPLE FORMED THEMSELVES INTO TRIBES FOR PROTECTION AGAINST DANGERS & ONE OF THEIR MOST IMPORTANT DEFENSES WAS A BELIEF IN THE PROTECTIVE POWER OF THEIR PERSONAL GODS.

As far as we know, human habitation in the Sahara Desert region dates back to c. 8000 BCE and these people migrated toward the Nile River Valley to settle in the lush region known as the Fayum (also Faiyum ). A farming community was established in this area as early as c. 5200 BCE and pottery has also been found in the same region dating to 5500 BCE. It should be noted that these dates relate only to established agrarian communities, not to the initial human habitation of the Fayum region which dates to c. 7200 BCE.

The Fayum in c. 5000 BCE was a lush paradise in which the people would have enjoyed fairly comfortable lives with abundant water and natural resources. At some point around 4000 BCE, however, a drought seems to have changed these ideal living conditions. The waters dried up and the wildlife moved on to find a more suitable environment.

The people who had established themselves in the region migrated toward the Nile River Valley and left the Fayum basin relatively deserted. These people then formed the communities which grew into the early Egyptian cities along the Nile River.This migration falls within the era known as the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000- c. 3150 BCE) before the establishment of a monarchy.

Nile Delta

At this time, it is thought the people formed themselves into tribes for protection against the environment, wild animals, and other tribes and one of their most important defenses against all these dangers was a belief in the protective power of their personal gods. Egyptologist and historian Margaret Bunson comments on this:

The Egyptians lived with forces that they did not understand. Storms, earthquakes, floods, and dry periods all seemed inexplicable, yet the people realized acutely that natural forces had an impact on human affairs. The spirits of nature were thus deemed powerful in view of the damage they could inflict on humans. (98).

In the same way that people recognized the ability of these forces to injure, however, they also believed the same could protect and heal. This early belief in supernatural forces was expressed in three forms:

• Animism - the belief that inanimate objects, plants, animals, and the earth have souls and are imbued with the divine spark;

• Fetishism - the belief that an object has consciousness and supernatural powers;

• Totemism - the belief that individuals or clans have a spiritual relationship with a certain plant, animal, or symbol.

In the Predynastic Period, animism was the primary understanding of the universe, as it was with early people in most cultures.Bunson writes, "Through animism humankind sought to explain natural forces and the place of human beings in the pattern of life on earth" (98). In time, animism led to the development of fetishism through the creation of symbols (such as the djed or ankh ) which both represented a higher concept and had its own innate powers.

Egyptian Djed

Fetishism then branched into totemism through the development of specific spiritual forces which watched over and guided an individual, a tribe, or community. Once totemism became the accepted understanding of how the world worked, these forces were anthropomorphized (given human characteristics) and these became the gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt.

These deities provided the foundation for the culture for the next 3,000 years. The gods had created the world, all the people in it, and established everything on the principle of harmony and balance. Ma'at was established at the creation of the world, empowered by heka (magic), and so harmony was valued in Egyptian culture as the defining concept of a stable and productive life.

THE LOWER CLASSES PROVIDED THE MEANS FOR THOSE ABOVE THEM TO LIVE COMFORTABLE LIVES & THE NOBILITY TOOK CARE OF THOSE UNDER THEM BY PROVIDING JOBS & DISTRIBUTING FOOD.

If one were living in balance, according to the will of the gods, one would enjoy a full life and, just as importantly, would contribute to the joy and success of one's community and, by extension, the country. Everyone benefited from knowing their place in the universe and what was expected from them and it was this understanding which gave rise to the social structure of the civilization.

THE SOCIAL CLASSES

As with most if not all civilizations from the beginning of recorded history, the lower classes provided the means for those above them to live comfortable lives, but in Egypt, the nobility took care of those under them by providing jobs and distributing food. Since the king represented the gods, and the gods had created the world, the king officially owned all the land. In keeping with ma'at, however, he could not just take from the people whatever he pleased but received goods and services through taxation. Taxes were levied and collected through the offices of the vizier and, once stored, these goods were then redistributed back to the people.

The jobs of the upper class are well known. The king ruled by delegating responsibility to his vizier who then chose the best people beneath him for the necessary tasks. Bureaucrats, architects, engineers, and artists carried out domestic building projects and the implementation of policies, and the military leaders took care of defense. The priests served the gods, not the people, and cared for the temple and the gods' statues while doctors, dentists, astrologers, and exorcists dealt directly with clients and their needs through their skills in magic and application of medicines.

One needed to work if one wanted to eat, but there was no shortage of jobs at any time in Egypt's history, and all labor was considered noble and respectable. Therefore, this redistribution was not a “handout” or charity but fair wages for one's labor.Egypt was a cashless society until the coming of the Persians in 525 BCE and so trade was conducted through the barter system based on a monetary unit known as the deben.

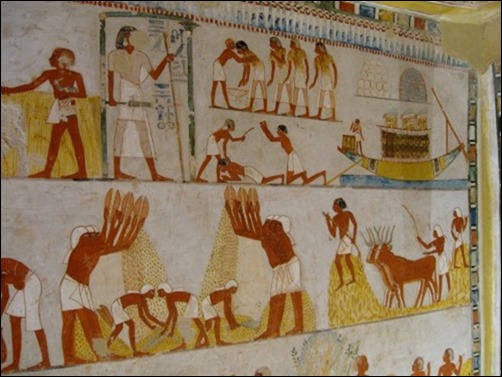

Sennedjem in the Afterlife

There was no actual deben coin but a deben represented the universally accepted monetary unit used to set the value of a product. If a woven mat cost one deben and a quart of beer cost the same, the mat could be traded fairly for the beer. Workers were regularly paid in beer for a day's labor as beer was considered healthier to drink than the waters of Egypt and was more nutritious but people were also paid in bread, clothing, and other goods for their work.

The details of the people's jobs are known from medical reports on the treatment of injuries, letters, and documents written on various professions, literary works (such as The Satire on the Trades ), tomb inscriptions, and artistic representations. This evidence presents a comprehensive view of daily work in ancient Egypt, how the jobs were done, and sometimes how people felt about their work. The Egyptians seem to have felt pride in their work no matter their occupation. Everyone had something to contribute to the community, and no skills were considered non-essential. The potter who produced cups and bowls was as important to the community as the scribe, and the amulet-maker as vital as the doctor.

Part of making a living, regardless of one's special skills, was taking part in the king's monumental building projects. Although it is commonly believed that the great monuments and temples of Egypt were achieved through slave labor - specifically that of Hebrew slaves - there is absolutely no evidence to support this claim. The pyramids and other monuments were built by Egyptian laborers who either donated their time as community service or were paid for their labor.

From the top of the hierarchy to the bottom, everyone understood their place and what was required of them for their own success and that of the kingdom. During most of Egypt's history this structure was adhered to and the culture prospered. Even during those eras known as “intermediate periods” – in which the central government was weak or even divided – the hierarchy of the society was recognized as unchangeable because it was so obvious that it worked and produced results.Toward the end of the New Kingdom, however, the system began to break down as those at the top began neglecting those at the bottom and members of the lower classes lost faith in their king.

Imhotep

DETERIORATION OF THE HIERARCHY

The king's primary duty was to uphold ma'at and maintain the balance between the people and their gods. In doing so, he needed to make sure that all of those below him were well cared for, that the borders were secure, and that rites and rituals were performed according to the accepted tradition. All of these considerations provided for the good of the people and the land as the king's mandate meant that everyone had a job and knew their place in the hierarchy of society. This hierarchy, however, began to break down toward the end of the reign of Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE) when the bureaucracy which helped maintain it floundered due to lack of resources.

Ramesses III is considered the last good pharaoh of the New Kingdom. He defended Egypt's borders, navigated the uncertainty of changing relations with foreign powers, and had the temples and monuments of the country restored and refurbished. He wanted to be remembered in the same way that Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) had been - as a great king and father to his people – and early in his reign he succeeded at this.

Egypt under Ramesses III, however, was not the supreme power it had been under Ramesses II and the country Ramesses III ruled over had suffered a loss in status with attendant diminishing resources from tribute and trade. These problems were caused by the expense of mounting a defense against the invasion by the Sea Peoples in 1178 BCE as well as well as the costs of maintaining the provinces of the Egyptian Empire.

THE STRIKE OF THE TOMB WORKERS SIGNALED THE BEGINNING OF THE END OF THE BELIEF SYSTEM WHICH SUPPORTED THE EGYPTIAN HIERARCHY.

Still, for over 20 years Ramesses III had done his best for the people and, as he approached his 30th year, plans were set in motion for a grand jubilee festival to honor him. The problem was that, unlike in the past, there simply were not the resources available to mount such an elaborate festival. In order to provide Ramesses III with his celebration, the needs of someone else further down the hierarchy would have to be sacrificed; this “someone else” turned out to be the highly-paid tomb workers at Deir el-Medina outside of Thebes.

These workers were among the most respected and well-compensated artisans in Egypt. They built and decorated the tombs of the kings and other nobility and, since these were considered the eternal homes of the deceased, those who worked on them were held in high esteem. In 1159 BCE, three years before Ramesses III's festival, the monthly wages of these workers arrived almost a month late. The scribe Amennakht, who also seems to have served as a kind of shop steward, negotiated with local officials for the distribution of corn to the workers but this was only a temporary solution to a serious problem: the failure of an Egyptian monarch to maintain balance in the land.

Instead of looking into what had caused the problem with delivery of the worker's wages, and trying to prevent it from happening again, officials continued on as though nothing was wrong in preparation for the grand festival. The payment to the workers at Deir el-Medina was again late and then again until, as Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson writes, “the system of paying the necropolis workers broke down altogether, prompting the earliest recorded strikes in history.” (335). The workers had waited for 18 days beyond their payday and refused to wait any longer. They lay down their tools and marched on Thebes to demand what they were owed.

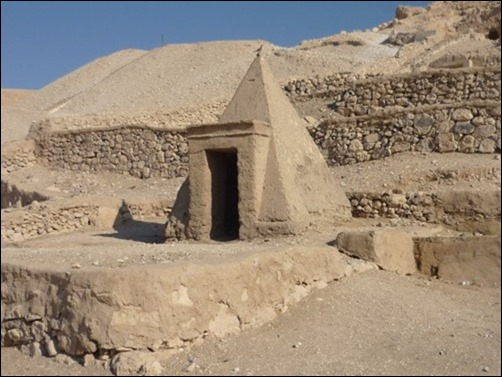

Worker's Tomb, Deir el-Medina

The officials at Thebes had no idea how to deal with this crisis because nothing like it had ever happened before. It was simply impossible, in their experience, for workers to refuse to do their jobs – much less mobilize and march on their superiors. After a number of insufficient remedies were attempted (such as trying to placate the workers by serving them pastries), the government found the means to pay them and the strike ended. The problem had not been resolved, however, and payment to the tomb workers would be late again in the coming years.

The strike of the tomb workers is significant because it signaled the beginning of the end of the belief system which supported the Egyptian hierarchy. The tomb workers were right in their protest: the king had failed them and, in so doing, had failed to maintain ma'at. It was not the job of these workers to recognize and uphold ma'at for the king – quite the reverse – and once balance was lost at the top of the hierarchy, faith was lost by those who made up the far more substantial base.

This is not to claim that Egyptian society fell apart following the tomb worker's strike of 1159 BCE. The hierarchy would continue in its traditional form throughout the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE) and on until Rome annexed Egypt in 30 BCE. Even though the social structure remained the same, however, the understanding of ma'at and the belief in the supremacy and divine nature of the king had changed and never fully regained its former strength in later periods.

This loss of faith affected the cohesion of the society and contributed to the further breakdown of the bureaucracy and the rule of law based on ma'at. Tomb robbing became more commonplace, as was corruption among police, priests, and government officials. When the Persians came in 525 BCE they found a very different Egypt than the great power of the days of empire ;once the foundational value of ma'at had been breached, all that had been built on it became unstable.

Amenhotep III › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Amenhotep III (c. 1386-1353 BCE) was the ninth king of the 18th dynasty of Egypt. He is also known as Nebma'atre, Amenophis III, Amunhotep II, and Amana-Hatpa, all of which relate to the concept of the god Amun being satisfied or, as in the case of Nebma'atre, with the ideal of satisfied balance. He was the son of the pharaoh Tuthmosis IV and his lesser wife Mutemwiya, husband of Queen Tiye, father of Akhenaten, and grandfather of Tutankhamun and Ankhsenamun. His greatest contribution to Egyptian culture was in maintaining peace and prosperity, which enabled him to devote his time to the arts. Many of the most impressive structures of ancient Egypt were built under his reign and, through military campaigns, he not only strengthened the borders of his land but expanded them. He ruled Egypt with Tiye for 38 years until his death and was succeeded by Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaten.

AMENHOTEP III'S OPULENT REIGN

Amenhotep's father, Tuthmosis IV, left his son an empire of immense size, wealth, and power. The Egyptologist Zahi Hawass writes, “Amenhotep III was born into a world where Egypt reigned supreme. Its coffers were filled with gold, and its vassals bowed down before the mighty rulers of the Two Lands [Egypt]” (27). He was only twelve years old when he came to the throne and married Tiye in a royal ceremony. It is a significant aspect of Amenhotep's relationship with his wife that, immediately after their marriage, she was elevated to the rank of Great Royal Wife, an honor which Amenhotep's mother, Mutemwiya, was never accorded and which effectively meant that Tiye outranked the king's mother in courtly matters.

AMENHOTEP III WAS A MASTER OF DIPLOMACY, SENDING LAVISH GIFTS OF GOLD TO OTHER NATIONS SO THEY WOULD BEND TO HIS WISHES, WHICH THEY INVARIABLY DID.

His marriage completed, the king set about continuing the policies of his father and implementing new building programs throughout Egypt. He was a master of diplomacy, who placed other nations in his debt through lavish gifts of gold so that they would be inclined to bend to his wishes, which they invariably did. His generosity to friendly kings was well established, and he enjoyed profitable relationships with the surrounding nations. He was also known as a great hunter and sportsman and boasted in an inscription that “the total number of lions killed by His Majesty with his own arrows, from the first to the tenth year [of his reign] was 102 wild lions” (Nardo, 19). Further, Amenhotep III was an adept military leader who “probably fought, or directed his military commanders, in one campaign in Nubia and he had inscriptions made to commemorate that expedition” (Bunson, 18). He maintained the honor of Egyptian women in refusing requests to send them as wives to foreign rulers, claiming that no daughter of Egypt had ever been sent to a foreign land and would not be sent under his reign. In all these ways, Amenhotep III emulated or improved upon his father's policies and in religion he did likewise. Amenhotep III was an ardent supporter of the ancient religion of Egypt and, in this, found a perfect outlet for his greatest interest: the arts and building projects.

MONUMENTAL CONSTRUCTIONS

The historian Durant describes the grandeur of Amenhotep's monuments in writing, “Two giants [sit] in stone, representing the most luxurious of Egypt's monarchs, Amenhotep III. Each is seventy feet high, weighs seven hundred tons, and is carved out of a single rock” (141). Amenhotep III's vision was of an Egypt so splendid that it would leave one in awe, and the over 250 buildings, temples, statuary, and stele he ordered constructed attest to his success in this. The statues which Durant mentions are today known as the Colossi of Memnon and are the only pieces left of Amenhotep III's mortuary temple. Their immense size and intricacy of detail, however, suggest that the temple itself – and his other building projects no longer extant – were equally or even more impressive.

Pharaoh Amenhotep III

Among these projects was the new pleasure palace at Malkata, on the west bank of the Nile, just across from the capital of Thebes. Bunson writes that “the vast complex was called `The House of Nebma'atre as Aten's Splendour.' The resort boasted a lake over a mile long, which appears to have been created in only 15 days by advanced hydraulic sluicing techniques. The complex contained residences for the Queen Tiye and for Akhenaten, the king's son and heir. Amenhotep even had a pleasure bark, dedicated to the god Aten, built for outings on the lake” (18). He frequently took these outings in the company of Tiye and, it seems, she was often his closest companion in both public and private life. Tiye, in fact, operated on a nearly equal, or completely equal, status to her husband and is often depicted in statuary as the same height as he is, symbolizing the harmony and equality of their relationship. While Amenhotep was busy with his building projects, Tiye took care of the affairs of state and running the palace complex at Malkata.

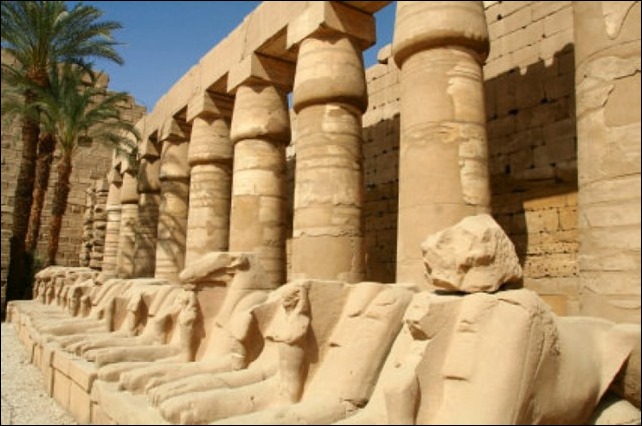

That she was kept quite busy with these tasks is evident in letters from foreign rulers as well as the number of buildings constructed during Amenhotep III's reign. In addition to those already mentioned, he had 600 statues of the goddess Sekhmet erected around the Temple of Mut, south of Karnak, renovated the existing Temple at Karnak, built temples to Amun, erected statuary depicting Amun, raised stele which recorded his accomplishments, set the granite lions in front of the Temple of Soleb in Nubia, and decorated walls and monuments with scenes depicting his exploits and the pleasure the gods had in him. In his first year of rule, he had new limestone quarries dug in the region of Tura and, throughout his reign, he depleted them. Images of the pharaoh and his gods spread across the plains and valleys of Egypt and cities were refurbished. Roads were improved and travel became easier. The ease of travel helped merchants get their wares to market more quickly and this, of course, boosted the economy. With revenue already coming in from vassal states, Egypt became increasingly wealthy under Amenhotep III's reign. The populace was content and the power of the throne was stable except for the threat from the priests of the cult of the god Amun.

THE SUN GOD & THE PRIESTS OF AMUN

There was another power in Egypt which had been growing long before Amenhotep III came to the throne: the cult of Amun.Land ownership meant wealth in Egypt and, by Amenhotep III's time, the priests of Amun owned almost as much land as the king. In accordance with traditional religious practice, Amenhotep III did nothing to interfere with the work of the priests, but it is thought that their immense wealth, and threat to the power of the throne, had a profound effect on his son. The god Aten was only one of many gods worshipped in ancient Egypt but, for the royal family, he had a special significance which would later become manifest in the religious edicts of Akhenaten. At this time, however, the god was simply another worshipped alongside the rest.

King Amenhotep III

Perhaps in an attempt to wrest some power from the priests of Amun, Amenhotep III identified himself with Aten more directly than any pharaoh had previously. Aten was a minor sun god, but Amenhotep III elevated him to the level of a personal deity of pharaoh. Hawass writes:

The sun god was a complex creature, whose dogma had been developing for thousands of years. In addition to his main incarnation as Re, this god was associated with the creator Atum as well as with deities such as Khepri…and Osiris, with whom Re merged at night. Another aspect of this god was the Aten; according to texts dating back at least to the Middle Kingdom, this was the disk of the sun, with which the king merged at death.This divine aspect, unusual in that it was not anthropomorphic, was chosen by Amenhotep III as a primary focus of his incarnation. It has been suggested that the rise of the Aten was linked specifically with maintenance of the empire, as the area over which, at least theoretically, the sun ruled. By associating himself with the visible disk of the sun, the king put himself symbolically over all the lands where it could be seen – all the known world, in fact (31).

Amenhotep III's elevation of Aten as his personal god was not uncommon. Pharaohs in the past were associated with a particular cult of a favored god and, obviously, Amenhotep III did not neglect the other gods in preference to Aten. If his goal in raising awareness of Aten was politically motivated, it did not accomplish very much at all during his reign. The cult of Amun continued to grow and amass wealth and, in doing so, continued to pose a threat to the royal family and the authority of the throne.

AMENHOTEP'S DEATH & THE REIGN OF AKHENATEN

Amenhotep III suffered from severe dental problems, arthritis, and possibly obesity in his final years. He wrote to Tushratta, the king of Mitanni (one of whose daughters, Tadukhepa, was among Amenhotep III's lesser wives) to send him the statue of Ishtar that had visited Egypt before, at his wedding to Tadukhepa, to heal him. Whether the statue was sent is a matter of controversy in the modern day and what, precisely, was ailing Amenhotep the III is likewise. It has been suggested that his dental problems resulted in an abscess which killed him but this has been disputed.

King Amenhotep III as a Lion

He died in 1353 BCE and letters from foreign rulers, such as Tushratta, express their grief on his passing and their condolences to Queen Tiye. These letters also make clear that these monarchs hoped to continue the same good relations with Egypt under the new king as they had with Amenhotep III. With Amenhotep III's passing, his son, then called Amenhotep IV, began his reign. At first, there was nothing which distinguished Amenhotep IV's rule from that of his father; temples were raised and monuments built just as before. In the fifth year of his reign, however, the new pharaoh underwent a religious conversion and outlawed the ancient religion of Egypt, closed the temples, and proscribed all religious practice. In place of the old faith, the king instituted a new one: Atenism. He changed his name to Akhenaten and created the first state mandated monotheistic system in the world.

Akhenaten continued to build monuments and temples just as his father had, but “these temples were not to Amun, but to the sun disk as the Aten” (Hawass, 36). The Aten was now the one true god of the universe and Akhenaten was the living embodiment of this god. The new king abandoned the palace at Thebes and built a new city, Akhetaten (`the horizon of Aten') on virgin land in the middle of Egypt. From his new palace he issued his royal decrees but seems to have spent most of his time on his religious reforms and neglected the affairs of state and, especially, foreign affairs. Vassal states, such as Byblos, were lost to Egypt, and the hopes which foreign rulers had expressed in continuing good relations with Egypt were disappointed.

Akhenaten's wife, Queen Nefertiti, assumed the responsibilities of her husband and, though she was adept at this, his neglect of his duties had already resulted in enormous loss of Egypt's wealth and prestige. During Akhenaten's reign, the treasury was slowly depleted, military discipline and efficacy was lax, and the people of Egypt, deprived of their traditional religious beliefs and the financial benefits associated with religious practices, suffered. Those who had once sold statuary or amulets or charms outside of temples no longer had a job, as the selling of such objects was illegal and those who worked in, or for, those temples were also unemployed. Foreign affairs were neglected as completely as the domestic and, by the time of Akhenaten's death in 1336 BCE, Egypt had fallen far from its height under the reign of Amenhotep III.

Akhenaten's son and successor, Tutankhamun, tried to reverse the fortunes of his country in the brief ten years of his reign but died at the age of 18 before he could accomplish his goals. He did, however, overturn his father's religious reforms, open the temples, and re-establish the old religion. His successor, Ay, continued these policies, but it would be Ay's successor, Horemheb, who would completely erase, or try to, the damage done to the country by Akhenaten's policies. Horemheb destroyed the city of Akhetaten, tore down the temples and monuments to Aten, and did this so thoroughly that later generations of Egyptians believed that he was the successor to Amenhotep III. Horemheb restored Egypt to the prosperity it had enjoyed before Akhenaten's reign, but Egypt never was able to manage the heights it had enjoyed under Amenhotep III, the luxurious pharaoh, diplomat, hunter, warrior, and great architect of Egyptian monuments.

Ammon › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Livius

Ammon is the name of a Libyan deity and his oracle in the desert. It became famous after Alexander the Great made a detour to consult the god. The modern name is Siwa.

ORACLE AT SIWA

Ammon was a Libyan deity, whose oracle was situated in the Siwa oasis, some 500 km west of Memphis, the capital of ancient Egypt. The oasis was also called Ammon. The Egyptians identified the god with their own supreme deity Amun ; they called god of the oracle "Amun of Siwa, lord of good counsel". The fact that the site was hard to reach, must have contributed to the feeling that an oracle from Ammon was something special - and therefore reliable.

The place is extremely hot; in the summer, the average temperatures range between 22º C during the night and 37º C during the day, with 48º C being a normal maximum. Until recently, the average annual rainfall was less than 8 mm; the global climate change, however, has changed this, and there have been several heavy rains in the first decade of the twenty-first centuries.This is disastrous, because the houses of Siwa have, for centuries, been made of dried mud. The site is dominated by hight artificial mounds ( shali ).

AMMON WAS A LIBYAN DEITY, WHOSE ORACLE WAS SITUATED IN THE SIWA OASIS, SOME 500 KM WEST OF MEMPHIS.

Because Siwa is located in a depression, the water table is comparatively high, varying between three meters below the surface to just 50 centimeters. As a consequence, there are many wells: 281 by one counting (eg, " Cleopatra 's Bath" - in Antiquity known as "Spring of the Sun"). Because they produce more water than evaporates, there are large, silty lakes east and west of the main settlement. The gardens of Siwa have always been located near the springs, and produce(d) olives and dates; barley and figs were less important.

Siwa was too far away and too isolated to be a real part of the Egyptian kingdom, but there may have been indirect control. We are certain that during the Nineteenth Dynasty, there was a fort north of Siwa, at Umm el-Rakham on the coast. This proves that the pharaohs were interested in the far west. After the fall of the New Kingdom, Siwa was certainly independent, and it is no strange idea that the Libyan kings of the Twenty-Second and Twenty-Third Dynasties were somehow related to the rulers of Siwa.

Ammon

Siwa finally became a fully integrated part of Egypt after the domestication of the dromedary had made desert travel easier, for example to Egypt in the east, the Cyrenaica in the northwest and the Nasamones in the west. Among the oasis' exports was salt.

A shrine was built by pharaoh Amasis (reign 570-526 BCE): a political act, intended to gain support from the Libyan tribes that had played a decisive role during Amasis' accession. A similar motive may have been behind the second temple, built by Nectanebo II (reign 359/358-342/341 BCE).

Amasis' sanctuary has been excavated on the acropolis, a shali hill now called Aghurmi, and is remarkable because it does not look like an Egyptian temple at all. In fact, the cult seems to have remained Libyan in nature, something that is more or less confirmed by the fact that the local ruler of the oasis is not depicted as Amasis' subject but as his equal. The cult of Ammon had been Egyptianized only superficially.

Zeus Ammon

GREEK AMMON

In the fifth century, the Greek researcher Herodotus of Halicarnassus stated in his Histories that the Lydian king Croesus(560-546 BCE) had offered sacrifices to the god Ammon. It is possible that Herodotus is right; after all, Croesus was allied to Amasis. Besides, by now, the cult had began to spread outside Egypt.

The first Greeks to visit the shrine were people from Cyrenaica, who knew the site through caravan trade. They called the god Zeus Ammon. Of course, Ammon is a bad rendering of Amun, but the name was nonetheless very fitting: ammos was the Greek word for "sand" - in other words, the Greeks called the god Sandy Zeus. His cult spread to the Greek world, and was especially propagated by the poet Pindar (522-445 BCE), who was the first Greek to dedicate an ode to the god and one of the first Greeks to erect a statue to the god. Later visitors included the Athenian commander Cimon, the Macedonian king Alexander the Great, and the Carthaginian leader Hannibal.

ROMAN PERIOD

In the Roman age, the oracle was not really forgotten, but there were not many visitors. Still, an inscription was found that dates to the reign of Trajan (98-117 CE), and of course there were people living at Siwa. Many tombs with Roman architectural elements have been found, suggesting substantial wealth in the first and second centuries CE. A mud-brick building may have been a Roman fort or a church, and we know of a sixth-century Christian leader named Ammoneki. After Islam arrived, the ancient oracle was converted into a mosque.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License