Wall Reliefs: Ashurnasirpal II's War Scenes at the British Museum › Anaximenes › Ancient Britain » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Wall Reliefs: Ashurnasirpal II's War Scenes at the British Museum › Origins

- Anaximenes › Who was

- Ancient Britain › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Wall Reliefs: Ashurnasirpal II's War Scenes at the British Museum › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin

THE MIGHTY KING

600 of their warriors I put to the sword and decapitated; 400 I took alive; 3,000 captives I brought forth; I took possession of the city for myself: the living soldiers, and heads to the city of Amidi the royal city, I sent.

( Annals of Assur-Nasir-Pal II 3.107).

Decapitated Heads of Assyrian Enemies

This is how Ashurnasirpal II (r. 884-859 BCE) recorded the way he had dealt with his enemies during one of his military campaigns. Most of the time, the overwhelming Assyrian Imperial army was led on the battlefield by an apparently heartless and harsh Assyrian King. The destiny of the defeated enemy, revolt, or turmoil, whether kings, princes, officers, soldiers, poor lay people, or children, should be an ever-lasting memorable event, a fatal lesson taught to anyone thinking, or may be thinking, of doing the same, threatening the crown and destabilising the Assyrian Empire. This propaganda of terror had to be documented and delivered to a wide-ranging audience, internal and external. Stelae, monuments, stones, and clay prisms were the media used to “broadcast” the King's achievements.

THIS ROOM WAS NOT CHOSEN HAPHAZARDLY, IT IS THE CORE OF THE KING'S COURT! ALL HAVE TO SEE & ABSORB THE MESSAGE.

How about the King's court, is it one of the key players? Every now and then, foreign rulers, high officials, ambassadors, messengers, and tribute bearers visit the King. Ashurnasirpal II had decorated the walls of his North-West Palace at the heart of the Assyrian Empire, Nimrud, with approximately 2-meter high alabaster bas-reliefs, depicting various scenes, like a movie in stone. The protagonist of the play, the title role, and the award winner, undoubtedly, was the King himself.

But, how about others, the supporting actors and actresses? It is not a monodrama after all! The throne room, Room B, of the North-West Palace was lined with war scenes of the so-called “victors and the vanquished” theme, depicting Ashurnasirpal II engaging in various military activities and charging his enemies. This room was not chosen haphazardly, it is the core of the King's court! All have to see and absorb the message.

Despite being out of context in Room 7 ( Assyria, Nimrud) of the British Museum, these reliefs undoubtedly make a lasting impression on the museum's visitors, as they have done in the past. I will concentrate on certain features and details, rather than the King himself, to demonstrate; these details are usually overlooked by the visitors. These wall panels were excavated by Sir Henry Layard in 1846 while unearthing the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Iraq. They reached the British Museum in 1849. I put an elaborate description below each image.

THE BATTLEFIELD ENVIRONMENT

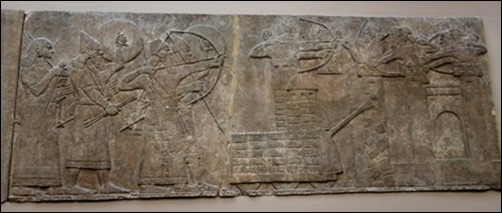

Ashurnasirpal II Attacks a City

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Panel 18 (top) of Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

An attack on a strongly walled city. The defenders, within crenellated turrets, are shooting arrows at the Assyrians. The battering ram of the Assyrian siege engine has repeatedly hit and finally broken the city's wall; bricks are falling. An Assyrian archer, standing within a wooden tower is shooting arrows at the enemy, within a short distance from the turrets, and he is guarded by a shield held by another soldier. Ashurnasirpal II stands behind the siege engine and shoots arrows at the foes. On his left side, a soldier holds a long spear and a shield to protect the King from the enemy's arrows. Behind the King, another soldier holds a shield, arrows, and a quiver of arrows. A royal attendant holding a bow, quiver, and mace stands behind the attackers. The scene is so vivid and so dynamic, as if it is an animated GIF image or a brief video clip.

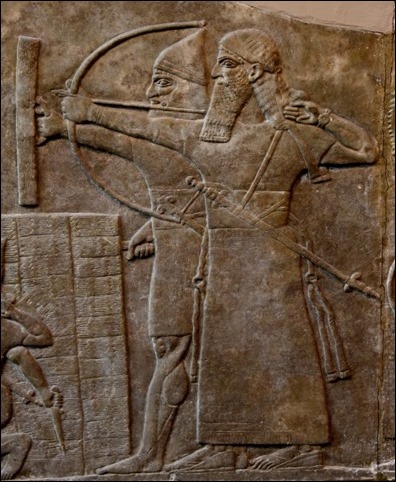

Crown Prince Shalmaneser III Attacks a City

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 4 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This bearded figure wearing a diadem with long lappets, elaborate costume, bracelet, and a long sword is not the King; he is the Crown Prince, Shalmaneser III, Ashurnasirpal II's son! Shalmaneser draws back the bowstring and is ready to shoot the enemy. Besides him, there is a soldier, holding a shield and a dagger to protect him.

Assyrian Archers Attacking a City

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 4 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

An Assyrian archer is kneeling and has drawn his bowstring back to shoot. His fellow also kneels and holds a dagger and a shield to protect him from enemy attacks. Above them and on the side of the siege engine, there appears to be an iron plate depicting a warrior wearing a horned helmet and shooting an arrow; this is a god, who stands beside the Assyrians to win the battle. Figures of deities commonly accompany armies. If you don't thoroughly scrutinize the whole panel, you will definitely miss this wonderful “evidence”.

ATTACK!

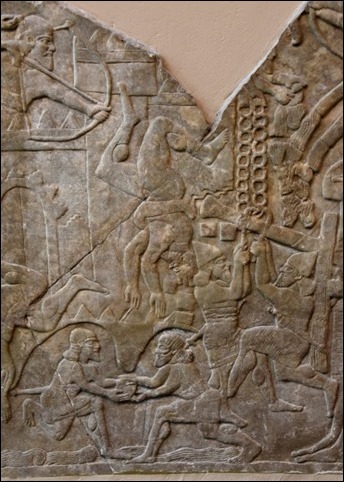

Assyrian Army Besiege a City

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 5 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The assault has begun and the attacking wave is overwhelming. A ladder has been lent on the city's wall. An Assyrian soldier climbs up the ladder and holds a shield for protection. Another soldier follows him. An Assyrian soldier stands between the ladder and the city wall and is holding a shield protecting another soldier who seems to crawl through a tunnel or a defect in the city's wall. Some of the defenders have been shot and killed and are falling from the turrets. The large shield on the left is held by an Assyrian soldier to protect Ashurnasirpal II, who is aiming at the turrets with a bow and arrow (not shown here).

Assyrian Soldiers Attacking a City

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 5 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The mid-upper part of this panel was lost but the remaining shows that an enemy soldier has lowered a long iron chain to divert the battering ram away from the city's wall. Meanwhile and to counteract this, two Assyrian soldiers are using hooks to pull down the chain. At the left upper turret, an enemy archer is aiming at those soldiers with his bow and arrow. At the upper right corner, the enemy has thrown torches on the siege engine. At the middle, an enemy soldier has fallen from the turret after being killed (shot by an arrow?). At the lower part near the river, two Assyrian soldiers are making a hole in the city's wall and the main tower, by removing the bricks/stones.

Assyrian Soldiers with Iron Crowbars

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 4 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Two Assyrian soldiers use iron crowbars to chisel out bricks from the city's wall. This will create a hole through which the Assyrian soldiers enter the city.

Assyrian Army Assaulting a City

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 4 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The Assyrian army attacks from all directions. The defenders within the turrets are perplexed and cannot stop the attacking wave. The woman on the long tower seems to lament.

NO ESCAPE

Fallen Foe of Assyrians

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 11 (top), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

A foe has fallen on the ground beneath one of the horses of an Assyrian war chariot. He was shot by two arrows in the back, which have penetrated deeply, up to the feathers. It looks like the man was trying to escape after his city was defeated and captured by the Assyrian army. The man's posture suggests that he is still alive but moribund. There are no weapons around him. The Assyrian sculptor seems to have exaggerated the foe's musculature; this would convey an image of a powerful and dangerous rival, which in turn reflects the Assyrian bravery.

Fallen Enemy of Assyrians

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 9 (top), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

An enemy has fallen beneath an Assyrian horse. He was either shot by one arrow in the lower back or that arrow was the only and final ammo he had. The quiver beside him is empty and the bow is on the ground. The man was out of ammo and tried to escape. He appears dead or is dying.

Decapitated Soldier, Assyrian Relief

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 9 (top), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This decapitated foe has fallen on the ground after being shot by two arrows in his back. There is an empty quiver and a bow beside him; another one who has failed escape after running out of arrows. Assyrian cavalry is passing over him.

Assyrian Enemies Trying to Escape

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 9 (top), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

On the right, an enemy soldier tries to pull his fellow soldier away in order to escape from an attacking, furious, and blood-thirsty Assyrian soldier; both of the retreating men appear unarmed.

Assyrian Soldiers Slaughtering their Enemies

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 9 (top), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Two enemy soldiers have escaped and tried desperately to hide among trees near their captured city. There is a river depicted in the lower part of the panel. Two Assyrian soldiers have seen their enemy and tried to seize their foes. On the left, the Assyrian soldier faces his foe and holds the head of the enemy with one hand and appears to thrust his dagger into the enemy's chest using the right hand. The collapsed enemy grips the Assyrian soldier's left arm and the attacking dagger. On the right, the enemy soldier tries to run away and turns his head towards his killer but the Assyrian soldier seems to push him using his shield and is about to stab him. What a dynamic and live broadcast!

Assyrian Soldier Kills His Enemy

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 8 (top), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

A desperate enemy soldier is semi-kneeling on the ground. An Assyrian soldier with a terrorizing look grips that man's scalp hair and slaughters him. There is a bow and a quiver full of arrows on the ground.

A FREE MEAL FOR VULTURES

Flocks of vultures were commonly depicted on Mesopotamian stelae and stone monuments, and wall reliefs of the North-West Palace were no exempt. Vultures attack dying or dead enemy soldiers on the battlefield. Predator birds still live in modern-day Iraq.

Predator Bird Attacks a Soldier

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 3 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

A vulture (or a predatory bird) plucks at a body of a dead enemy soldier. The vulture's wings, beak, and talons reflect an attacking posture.

Vulture Attacking a Dead Soldier

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 11 (top), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The body gesture of this enemy soldier suggests that he is already dead; a vulture (or a predatory bird) pecks out his eye.

IT'S TIME FOR DECAPITATION

Decapitation was commonly depicted on Assyrian wall reliefs. What does this reflect? Possibly, a victorious soldier who really hates his enemy and who feels an extreme pleasure while cutting the throat of his foe. In addition, documenting this event visually is a way of broadcasting victory and is a threat message to potential enemies.

Decapitated Heads of Assyrian Enemies

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 6 (top), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Two Assyrian soldiers hold the decapitated heads of their enemies before musicians (two lyre players and one tambourine player); they are celebrating their victory immediately on the battlefield. These vivid and graphic images directly reflect what's happening in the triumphal environment; the voice of agony, the sight of death, and the odour of blood are mixed with music.

![clip_image001[1] clip_image001[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj2iSQWc-h1MOo40gjvU9A6klKpn5BpzJj_Cs-39Zie-w3IsrtUthSKluybi5L-cHs9uLX1wU46Ya4EyQ-Dot-pmcbT-8AvrK7eWQDErxvrzlouIQL9M7XQmTBLI7ldAHQ22Td6xqfLK2I/?imgmax=800)

Decapitated Heads of Assyrian Enemies

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 6 (top), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Those Assyrian soldiers are perhaps playing catch or, less likely, counting and stacking the decapitated heads of their enemies.

THE FINALE

Assyrian Prisoners of War

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 5 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Two women and a child are walking away and are led by an Assyrian soldier to join a procession of prisoners. Civilians were either taken prisoner (and they might engage in construction work) or simply deported to live in other areas of the Assyrian Empire; they were unlikely to be killed.

Prisoners of War & Booty

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Panel 17 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This complete panel documents and broadcasts the typical tell-tale review of the prisoners and booty theme. Ashurnasirpal II stands (depicted on the panel on the left, not shown here in this image) to receive the booty and review the prisoners of war.The latter group cannot access the sacred figure of the King; they require an intermediary, as in all such Assyrian events. On the left, two bearded Assyrian officials are accompanied by two beardless attendants of the King (all have their swords hanging on their side), approaching the King in great dignity. Behind them, there is a person, distinguished from all other kinds of staff, who brings up the rear of the officials. He is recognizable by his humble page-boy hair style. The head of the group of prisoners is behind this man; an Assyrian soldier grasps his head in a humiliating gesture. Three more prisoners follow and another Assyrian soldier holding a bow and a sword completes the row and pushes the procession forward in disgrace and dishonour. Every now and again, a new element relieves the monotony. That page-boy haired man looks at his superior (not shown here), thus scrutinizing the procession, and therefore putting the King in context, so as not to miss even the slightest gesture. His left arm is raised to indicate another group to come forward. The booty is depicted on the upper part of the panel, in mid-air; cauldrons and ivory tusks were mentioned in the list of booty.

Ashurnasirpal II After Winning a Battle

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Panel 17 (bottom), Room B, the North-Palace Palace, Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

Concluding with a final triumph scene; the battle has ended and the Assyrians got a landslide victory. Ashurnasirpal II, after dismounting from the royal chariot, stands majestically under a parasol held by an attendant. The King wears his elegant royal costume and accessories well as a full set of weaponry. The King holds a bow and arrows; the victorious warrior. A figure greets the King in close proximity, almost touching him; he is recognizable by his long sword hanging by his side and the long curly beard. This denotes a person of the highest rank. This is “Turtanu” in Assyrian, the Chief-in-Command of the King and second in command of the whole Assyrian Empire. A soldier bows before the King, almost kissing his sandals; this is not a compelled enemy, but an Assyrian soldier who has probably distinguished himself in the fighting. Behind the King, stand his royal attendants and bodyguards. The king's chariot and the horses were exquisitely carved and the harness was depicted in a marvellous way; horses with feathered crowns were royal. The King is about to review a procession of courtiers and prisoners of war.

I had a Nikon D610 camera at that time. I spent about an hour, taking approximately 1000 zoomed-in images of the above reliefs. After I shot the pictures, I stepped backwards and observed visitors of the British Museum when they were passing through Room 7 on the Ground Floor. The above reliefs were placed on a single long wall and were arranged in two horizontal and parallel rows. An average of “20 seconds” those visitors had spent to see this short but detailed film in stone. Finally, Iinterrupted a tour guide (of course in a polite way) leading a large group from South-East Asia and asked him what his group has learned? All of them said that they have enjoyed these panels. I asked his permission to show them, briefly, some important details, such as the images above; they were very impressed and started to take detailed images of the reliefs! I did not include many wonderful zoomed-in images, because I cannot put all details in this article.

Yes, it is understandable that when you visit a great museum, such as the British Museum, you will be in a hurry! But, please spend some time at some points, and scrutinize rather than just passing by. I hope that I was successful in conveying this wonderful but graphic Assyrian art from my country, Iraq, currently housed in the British Museum. Viva Mesopotamia !

This article was written in memory of war victims all over the World; their spirits still linger among us, but do they watch us?!

We are all damaged goods. We mourn when we are victims and rejoice at our enemies' misery. We pray for the victory of our fighters and the demise of the enemies. We don't do anything in between. No one talks to anyone.We just shoot or cry.

Sam Wazan, “Trapped in Four Square Miles”.

Anaximenes › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Anaximenes of Miletus (c 546 BCE) was a younger contemporary of Anaximander and generally regarded as his student.Known as the Third Philosopher of the Milesian School (after Thales and Anaximander) Anaximenes proposed air as the First Cause from which all else comes (differing from Thales, who claimed water was the source of all things, or Anaximander, who cited 'the boundless infinite'). To the Greeks of the time, `air' was comparable to `soul' and, just as one's breath gave an individual life, so air, Anaximenes claimed, gave life to all observable phenomena. He explained the process by which the First Cause creates the observable world in this way:

Air differs in essence in accordance with its rarity or density. When it is thinned it becomes fire, while when it is condensed it becomes wind, then cloud, when still more condensed it becomes water, then earth, then stones.Everything else comes from these. (DK13A5)

To Anaximenes, everything was in a constant state of change owing to the property of air and how it is always in flux. The world itself, he claimed, was created by air through a process he compared to the process of felting, by which wool is compressed to create felt. In this same way was the earth created through compression of air which, through a process of evaporation, gave birth to the stars and the planets. All of life came from this same sort of process, of air being compacted to change itself, or another, into a different thing.

In this way, Anaximenes provided a basis for rational discourse and debate on his claim and laid the groundwork for future scientific inquiry into the nature of existence. His influence is far reaching.

Anaximenes' theory of successive change of matter by rarefaction and condensation was influential in later theories. It is developed by Heraclitus (DK22B31), and criticized by Parmenides (DK28B8.23-24, 47-48).Anaximenes' general theory of how the materials of the world arise is adopted by Anaxagoras (DK59B16), even though the latter has a very different theory of matter. Both Melissus (DK30B8.3) and Plato ( Timaeus 49b-c) see Anaximenes' theory as providing a common-sense explanation of change. Diogenes of Apollonia makes air the basis of his explicitly monistic theory. The Hippocratic treatise On Breaths uses air as the central concept in a theory of diseases. By providing cosmological accounts with a theory of change, Anaximenes separated them from the realm of mere speculation and made them, at least in conception, scientific theories capable of testing. ( Encyclopedia of Philosophy )

Like Thales and Anaximander before him, Anaximenes sought an underlying reason for existence and natural phenomena without appealing to the tradition of supernatural deities as the First Cause. Even though, like the other Milesians, he is never quoted as teaching atheism, there is nothing theistic in any of the extant fragments of his writings nor in any of the references to him by ancient writers. According to Diogenes Laertius, Anaximenes "wrote in the pure unmixed Ionian dialect. And he lived, according to the statements of Apollodorus, in the sixty-third Olympiad, and died about the time of the taking of Sardis "

His influence is especially noticeable in the philosophy of the later writer Heraclitus, as noted above, who developed the concept of Flux as a First Cause in and of itself.

His influence is especially noticeable in the philosophy of the later writer Heraclitus, as noted above, who developed the concept of Flux as a First Cause in and of itself.

(Citations DK in reference to the Diels/Krantz work The Fragments of the Pre-Socratics, 1967).

Ancient Britain › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Terry Walsh

Britain (or more accurately, Great Britain) is the name of the largest of the British Isles, which lie off the northwest coast of continental Europe. The name is probably Celtic and derives from a word meaning 'white'; this is usually assumed to be a reference to the famous white Cliffs of Dover, which any new arrival to the country by sea can hardly miss. The first mention of the island was by the Greek navigator Pytheas, who explored the island's coastline, c. 325 BCE.

During the early Neolithic Age (c. 4400 BCE – c. 3300 BCE), many long barrows were constructed on the island, many of which can still be seen today. In the late Neolithic (c. 2900 BCE – c.2200 BCE), large stone circles called henges appeared, the most famous of which is Stonehenge.

Before Roman occupation the island was inhabited by a diverse number of tribes that are generally believed to be of Celtic origin, collectively known as Britons. The Romans knew the island as Britannia.

It enters recorded history in the military reports of Julius Caesar, who crossed to the island from Gaul (France) in both 55 and 54 BCE. The Romans invaded the island in 43 CE, on the orders of emperor Claudius, who crossed over to oversee the entry of his general, Aulus Plautius, into Camulodunum (Colchester), the capital of the most warlike tribe, the Catuvellauni.Plautius invaded with four legions and auxiliary troops, an army amounting to some 40,000.

Due to the survival of the Agricola, a biography of his father-in-law written by the historian Tacitus (c. 105 CE), we know much about the first four decades of Roman occupation, but literary evidence is scarce thereafter; happily there is plentiful, if occasionally mystifying archaeological evidence. Subsequent Roman emperors made forays into Scotland, although northern Britain was never conquered; they left behind the great fortifications, Hadrian 's Wall (c. 120 CE) and the Antonine Wall (142 -155 CE), much of which can still be visited today. Britain was always heavily fortified and was a base from which Roman governors occasionally made attempts to seize power in the Empire (Clodius Albinus in 196 CE, Constantine in 306 CE).

At the end of the 4th century CE, the Roman presence in Britain was threatened by "barbarian" forces. The Picts (from present-day Scotland) and the Scoti (from Ireland ) were raiding the coast, while the Saxons and the Angles from northern Germany were invading southern and eastern Britain. By 410 CE the Roman army had withdrawn. After struggles with the Britons, the Angles and the Saxons emerged as victors and established themselves as rulers in much of Britain during the Dark Ages (c. 450 - c. 800 CE).

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License