Assur › Assyria › Studying History & Evaluating Sources › Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Assur › Who was

- Assyria › Origins

- Studying History & Evaluating Sources › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Assur › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Assur (also Ashur , Anshar) is the god of the Assyrians who was elevated from a local deity of the city of Ashur to the supreme god of the Assyrian pantheon . The Assyrian Empire , like the later empire of the Romans, had a great talent for borrowing from other cultures. This penchant is illustrated clearly in the figure of Assur whose character and attributes draw on the Sumerian and Babylonian gods. Assur's family and history are modeled on the Sumerian Anu and Enlil and the Babylonian Marduk ; his power and attributes mirror Anu's, Enlil's, and Marduk's as do details of his family: Assur's wife is Ninlil (Enlil's wife) and his son is Nabu (Marduk's son). Assur had no actual history of his own, such as those created for Sumerian and Babylonian gods but borrowed from these other myths to create a supreme deity whose worship, at its height, was almost monotheistic. Scholar Jeremy Black notes:

In spite of (or possibly because of) the tendencies to transfer to him the attributes and mythology of other gods, Assur remains an indistinct deity with no clear character or tradition (or iconography) of his own. (38)

ASSUR HAD NO ACTUAL HISTORY OF HIS OWN BUT BORROWED FROM OTHER MYTHS TO CREATE A SUPREME DEITY WHOSE WORSHIP, AT ITS HEIGHT, WAS ALMOST MONOTHEISTIC.

Assur had power over the kingship of Assyria but, in this, was no different from Marduk of Babylon . The king of Assyria was his chief priest and all those who tended his temple in the city of Ashur and elsewhere lesser priests. Assyrian kings frequently chose his name as an element in their own to honor him ( Ashurbanipal , Ashurnasirpal I, Ashurnasirpal II , etc). Worship of Assur consisted, as with other Mesopotamian deities, of priests tending the statue of the god in the temple and taking care of the duties of the complex surrounding it. Although people may have engaged in private rituals honoring the god or asking for assistance, there were no temple services as one would recognize them in the modern day.

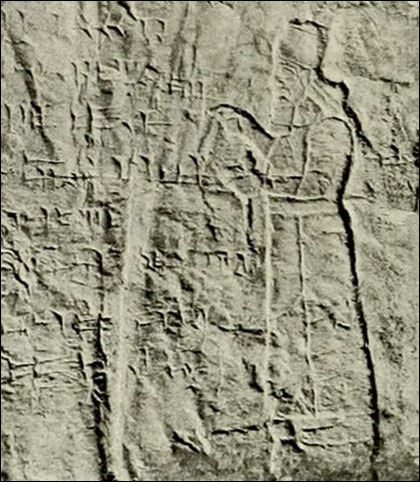

The iconography of Assur is often taken from the Sumerian Anu, a crown or a crown on a throne, but he is as frequently represented as a warrior-god wearing a horned helmet and carrying a bow and quiver of arrows. He wears a short skirt of feathers and is sometimes depicted within a winged disk (although the association of Assur with the solar disk is contested by a number of modern scholars, among them Jeremy Black). Assur is also sometimes represented standing on a snake-dragon, an image borrowed from the Babylonian Marduk, among other gods.

EARLY ORIGINS

Assur is first positively attested to in the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE) of Mesopotamian history. He is identified as the patron god of the city of Ashur c. 1900 BCE at its founding and also gives his name to the Assyrians. From a local, and probably agricultural, god who personified the city, Assur steadily acquired greater and greater attributes. The scholar EA Wallis Budge describes the general progression gods made from spirits to local deities to supreme gods:

The oldest of such spirits was the "house spirit" or household-god. When men formed themselves into village communities the idea of the "spirit of the village" was evolved and later came the "god of the town or city" and the "god of the country". Each of the elements, earth, air, fire, and water had its spirit or "god", the earthquake, lightning, thunder, rain, storm, desert whirlwind, each likewise its spirit or "god", and of course each plant, tree, and animal. As time went on, men began to think that certain spirits were more powerful than others and these they selected for special reverence or worship. (81-82)

Such was the case with Assur in that he is originally referenced as the god of only the locale surrounding the city but came to personify and represent the entire nation of Assyria. His city mirrored his rise to fame as Ashur began as a small trading center built on the site of an earlier community founded by Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 BCE) but flourished through trade with Anatolia and with other regions of Mesopotamia to become the capital of Assyria by the time of the reign of the Assyrian king Shamashi Adad I (1813-1791 BCE). Shamashi Adad I drove the Amorites from the region in Assur's name and secured his boundaries but was defeated by the Amorite king Hammurabi of Babylon (1792-1750 BCE) who then controlled the region.Worship of Assur at this time was restricted to the city and the Assyrian lands surrounding it, while Marduk of Babylon was worshiped as the supreme god and the Babylonian work Enuma Elish was considered the authoritative piece on creation and the birth of the gods and humanity.

Ashurbanipal II Attacking Enemy Archers

RISE TO POWER

In the tumult following Hammurabi's death, different powers controlled the region and their gods were considered supreme.The Mitanni and the Hittites both held Ashur and Assyrian areas as a vassal state until they were defeated by king Adad Nirari I (1307-1275 BCE), who united the lands under the first semblance of an Assyrian empire. Assur is credited by the king as the god who granted him the victory, but no history of the god existed to glorify. Scholar Jeremy Black comments on this:

Eventually, with the growth of Assyria and the increase in cultural contacts with southern Mesopotamia, there was a tendency to assimilate Assur to certain of the major deities of the Sumerian and Babylonian pantheons.From about 1300 BCE we can trace some attempts to identify him with Sumerian Enlil. This probably represents an effort to cast him as the chief of the gods...Then, under Sargon II of Assyria (reigned 722-705 BCE), Assur tended to be identified with Anshar, the father of Anu (An) in the Babylonian Epic of Creation. The process thus represented Assur as a god of long-standing, present from the creation of the universe. (37-38)

From the time of Adad Nirari I to the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire of Sargon II, Assur continued to rise in prominence. In the Enuma Elish , Assur (under the name Anshar) replaced Marduk as the hero. Tiglath Pileser I (1115-1076 BCE) regularly invokes Assur as the god of the empire who empowers the army and leads them to victory and even credits Assur with the laws of the empire. Adad Nirari II (912-891 BCE) expanded the empire in every direction with Assur as his personal patron.Everywhere the Assyrian army traveled, Assur traveled with them, and thus his worship spread across Mesopotamia. Wallis Budge writes, "As the power of Marduk became predominant when Babylon grew into a great city, so the power of Assur waxed great when the Assyrians became a strong and warlike nation" (88). To the men who marched in the Assyrian forces, as well as to those they conquered, Assur was obviously a powerful god worthy of worship and devotion and, in time, he became so powerful as to eclipse the earlier gods of the region.

ASSUR, THE SUPREME GOD

When Ashurnasirpal II (884-859 BCE) came to power, he moved the capital of the empire from Ashur to the city of Kalhu , but this is no indication of waning power on Assur's part; Ashurnasirpal II had Assur's name as part of his own (his name means 'Assur is Guardian of the Heir'). The reason for the capital's move is unclear, but most likely it was only because Ashur had grown so great and the populace fiercely proud and Ashurnasirpal II wanted to surround himself with humbler and more easily manageable people. Tiglath Pileser III (745-727 BCE) elevated Assur's name even higher through the stunning victories which marked his reign. Tiglath Pileser III created the first professional army in the history of the world, who, armed with iron weapons, were invincible. Along with the new kind of army, new technology was created such as siege engines which allowed the army to take whole cities with fewer losses.

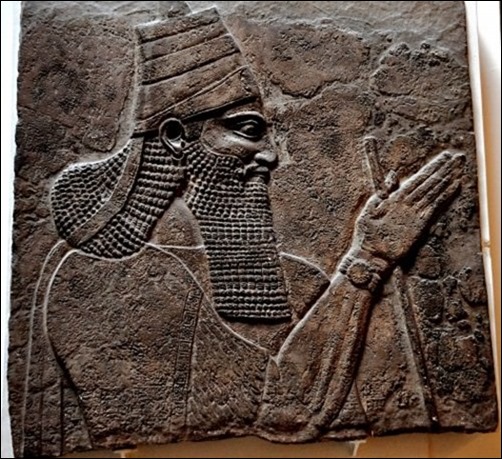

King Tiglath-pileser III

As the Assyrian armies campaigned throughout the land, Assur led them to greater and greater victories. Previously, however, Assur had been linked with the temple of the city of Ashur and had only been worshiped there. As the Assyrians made wider and wider gains in territory, a new way of imagining the god became necessary in order to continue that worship in other locales. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek explains how, in order to maintain worship of Assur, the nature of a god - and how that god should be understood and worshiped - had to change:

One might pray to Assur not only in his own temple in his own city, but anywhere. As the Assyrian empire expanded its borders, Assur was encountered in even the most distant places. From faith in an omnipresent god to belief in a single god is not a long step. Since He was everywhere, people came to understand that, in some sense, local divinities were just different manifestations of the same Assur. (231)

This unity of vision of a supreme deity helped to further unify the regions of the empire. The different gods of the conquered peoples and their various religious practices became absorbed into the worship of Assur, who was recognized as the one true god who had been called different names by different people in the past but who now was clearly known and could be properly worshiped as the universal deity. Regarding this, Kriwaczek writes:

Belief in the transcendence rather than immanence of the divine had important consequences. Nature came to be desacralized, deconsecrated. Since the gods were outside and above nature, humanity – according to Mesopotamian belief created in the likeness of the gods and as servant to the gods – must be outside and above nature too. Rather than an integral part of the natural earth, the human race was now her superior and her ruler.The new attitude was later summed up in Genesis 1:26: 'And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let him have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth' That is all very well for men, explicitly singled out in that passage. But for women it poses an insurmountable difficulty. While males can delude themselves and each other that they are outside, above, and superior to nature, women cannot so distance themselves, for their physiology makes them clearly and obviously part of the natural world…It is no accident that even today those religions that put most emphasis on God's utter transcendence and the impossibility even to imagine His reality should relegate women to a lower rung of existence, their participation in public religious worship only grudgingly permitted, if at all. (229-230)

Women in Mesopotamia had enjoyed almost equal rights with men until the rise of Hammurabi and his god Marduk. Under Hammurabi's reign, female deities began to lose prestige as male gods became increasingly elevated. Under Assyrian rule, with Assur as supreme god, women's rights suffered further. Cultures like the Phoenicians , who had always regarded women with great respect, were forced to follow the customs and beliefs of the conquerors. The Assyrian culture became increasingly cohesive with the expansion of the empire, the new understanding of the deity, and the assimilation of the people from the conquered regions. Shalmaneser III (859-824 BCE) expanded the empire up through the coast of the Mediterranean and received regular tribute from wealthy Phoenician cities such as Tyre and Sidon .

Assur was now the supreme god not only of the Assyrians but of all those people who were brought under their rule. To the Assyrians, of course, this was an ideal situation, but this opinion was not shared by every nationality they had conquered, and when the opportunity presented itself, they would vent their frustrations dramatically.

THE END OF ASSUR

The Neo-Assyrian Empire (912-612 BCE) is the last expression of Assyrian political power in Mesopotamia and is the one most familiar to students of ancient history. The kings of this period are the ones most often mentioned in the Bible and best known by people in the present day. It is also the era which most decisively gives the Assyrian Empire the reputation it has for ruthlessness and cruelty. Kriwaczek comments on this, writing :

Assyria must surely have among the worst press notices of any state in history. Babylon may be a byname for corruption, decadence and sin but the Assyrians and their famous rulers, with terrifying names like Shalmaneser, Tiglath-Pileser , Sennacherib , Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, rate in the popular imagination just below Adolf Hitler and Genghis Khan for cruelty, violence, and sheer murderous savagery. (208)

Although there is no denying the Assyrians could be ruthless and were quite clearly not to be trifled with, they were really no more savage or barbaric than any other ancient civilization . In order to form and maintain an empire, they destroyed cities and murdered people, but in this, they were no different from those who preceded and followed them, save in that they were easily more efficient than most.

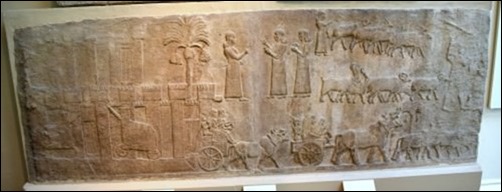

Assyrian Deportation of People from Southern Iraq

To the conquered people, however, the Assyrians were seen as hated overlords. The last great king of the empire was Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE) and, after him, the empire began to break apart. There were many reasons for this but, mainly, it had simply grown too large to manage. As the power of the central government became less and less able to cope, more territories broke away from the empire. In 612 BCE a coalition of Babylonians, Medes, Persians, and others rose against the Assyrian cities and destroyed them. Included in this onslaught was the city of Ashur and the temple of the god as well as other statues of Assur elsewhere. Assur had come to personify the Assyrians, their military victories, and their political power, and so the destruction of this symbol was of special importance to Assyria's enemies.

Worship of Assur continued in Assyrian communities after the fall of the empire but was no longer widespread and no temples, shrines, or statuaries were left standing in the cities and regions which had revolted. In the early Christian era, the understanding of Assur as an omnipotent deity worked well for the early Christian missionaries to the region, who found the Assyrians receptive to their message of a single god and the concept of this god's son coming to earth for the benefit of humanity. Although Assur's son Nabu never became incarnated or sacrificed himself for others, he was thought to have given human beings the gift of the written word. Nabu continued to be venerated after the fall of the empire, and although Assur declined in stature, he was remembered and is still present (often as Ashur) as a personal and family name in the present day.

Assyria › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Assyria was the region in the Near East which, under the Neo-Assyrian Empire , reached from Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) through Asia Minor (modern Turkey ) and down through Egypt . The empire began modestly at the city of Ashur(known as Subartu to the Sumerians ), located in Mesopotamia north-east of Babylon , where merchants who traded in Anatolia became increasingly wealthy, and that affluence allowed for the growth and prosperity of the city. According to one interpretation of passages in the biblical Book of Genesis, Ashur was founded by a man named Ashur son of Shem, son of Noah, after the Great Flood, who then went on to found the other important Assyrian cities . A more likely account is that the city was named Ashur after the deity of that name sometime in the 3rd millennium BCE; the same god's name is the origin for `Assyria'. The biblical version of the origin of Ashur appears later in the historical record after the Assyrians had accepted Christianity , and so it is thought to be a re-interpretation of their early history which was more in keeping with their belief system. The Assyrians were a Semitic people who originally spoke and wrote Akkadian before the easier to use Aramaic language became more popular. Historians have divided the rise and fall of the Assyrian Empire into three periods: The Old Kingdom , The Middle Empire, and The Late Empire (also known as the Neo-Assyrian Empire), although it should be noted that Assyrian history continued on past that point, and there are still Assyrians living in the regions of Iran and Iraq, and elsewhere, in the present day. The Assyrian Empire is considered the greatest of the Mesopotamian empires due to its expanse and the development of the bureaucracy and military strategies which allowed it to grow and flourish.

THE OLD KINGDOM

Although the city of Ashur existed from the 3rd millennium BCE, the extant ruins of that city date to 1900 BCE which is now considered the date the city was founded. According to early inscriptions, the first king was Tudiya, and those who followed him were known as “kings who lived in tents” suggesting a pastoral, rather than urban, community. Ashur was certainly an important centre of commerce even at this time, however, even though its precise form and structure is unclear. The king

THE DESTRUCTION OF THE GREAT ASSYRIAN CITIES WAS SO COMPLETE THAT, WITHIN TWO GENERATIONS OF THE EMPIRE'S FALL, NO ONE KNEW WHERE THE CITIES HAD BEEN.

Erishum I built the temple of Ashur on the site in c. 1900/1905 BCE, and this has come to be the accepted date for the founding of an actual city on the site although, obviously, some form of city must have existed there prior to that date. The historian Wolfram von Soden writes,

Because of a dearth of sources, very little is known of Assyria in the third millennium…Assyria did belong to the Empire of Akkad at times, as well as to the Third Dynasty of Ur . Our main sources for this period are the many thousand Assyrian letters and documents from the trade colonies in Cappadocia, foremost of which was Kanesh (modern Kultepe) (49-50).

The trade colony of Karum Kanesh (the Port of Kanesh) was among the most lucrative centres for trade in the ancient Near East and definitely the most important for the city of Ashur. Merchants from Ashur traveled to Kanesh, set up businesses, and then, after placing trusted employees (usually family members) in charge, returned to Ashur and supervised their business dealings from there. The historian Paul Kriwaczek notes:

For several generations the trading houses of Karum Kanesh flourished, and some became extremely wealthy – ancient millionaires. However not all business was kept within the family. Ashur had a sophisticated banking system and some of the capital that financed the Anatolian trade came from long-term investments made by independent speculators in return for a contractually specified proportion of the profits. There is not much about today's commodity markets that an old Assyrian would not quickly recognize (214-215).

THE RISE OF ASHUR

The wealth generated from trade in Karum Kanesh provided the people of Ashur with the stability and security necessary for the expansion of the city and so laid the foundation for the rise of the empire. Trade with Anatolia was equally important in providing the Assyrians with raw materials from which they were able to perfect the craft of iron working. The iron weapons of the Assyrian military would prove a decisive advantage in the campaigns which would conquer the entire region of the Near East. Before that could happen, however, the political landscape needed to change. The people known as the Hurrians and the Hatti held dominance in the region of Anatolia, and Ashur, to the north in Mesopotamia, remained in the shadow of these more powerful civilizations. In addition to the Hatti, there were the people known as the Amorites who were steadily settling in the area and acquiring more land and resources. The Assyrian king Shamashi Adad I (1813-1791 BCE) drove the Amorites out and secured the borders of Assyria, claiming Ashur as the capital of his kingdom. The Hatti continued to remain dominant in the region until they were invaded and assimilated by the Hittites in c. 1700. Long before that time, however, they ceased to prove as major a concern as the city to the southwest which was slowly gaining power: Babylon. The Amorites were a growing power in Babylon for at least 100 years when the Amorite king named Sin Muballit took the throne, and, in c. 1792 BCE, his son King Hammurabi ascended to rule and subjugated the lands of the Assyrians. It is around this same time that trade between Ashur and Karum Kanesh ended, as Babylon now rose to prominence in the region and took control of trade with Assyria.

King Hammurapi at Worship

Soon after Hammurabi's death in 1750 BCE, the Babylonian Empire fell apart. Assyria again attempted to assert control over the region surrounding Ashur, but it seems as though the kings of this period were not up to the task. Civil war broke out in the region, and stability was not regained until the reign of the Assyrian king Adasi (c. 1726-1691 BCE). Adasi was able to secure the region and his successors continued his policies but were unable or unwilling to engage in expansion of the kingdom.

THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

The vast Kingdom of Mitanni rose from the area of eastern Anatolia and now held power in the region of Mesopotamia;Assyria fell under their control. Invasions by the Hittites under King Suppiluliuma I broke Mitanni power and replaced the kings of Mitanni with Hittite rulers at the same time that the Assyrian king Eriba Adad I was able to gain influence at the Mitanni (now mainly Hittite) court. The Assyrians now saw an opportunity to assert their own autonomy and began to expand their kingdom outward from Ashur to the regions previously held by the Mitanni. The Hittites struck back and were able to hold the Assyrians at bay until the king Ashur-Uballit I (c.1353-1318 BCE) defeated the remaining Mitanni forces under the Hittite commanders and took significant portions of the region. He was succeeded by two kings who maintained what had been won, but no further expansion was achieved until the coming of King Adad Nirari I (c. 1307-1275 BCE) who expanded the Assyrian Empire to the north and south, driving out the Hittites and conquering their major strongholds. Adad Nirari I is the first Assyrian king about whom anything is known with certainty, because he left inscriptions of his achievements which have survived mostly intact. Further, letters between the Assyrian king and the Hittite rulers have also survived and make it clear that, initially, the Assyrian rulers were not taken seriously by those of other nations in the region until they proved themselves too powerful to resist. The historian Will Durant comments on the rise of the Assyrian Empire writing :

If we should admit the imperial principle – that it is good, for the sake of spreading law, security, commerce and peace, that many states should be brought, by persuasion or force, under the authority of one government – then we should have to concede to Assyria the distinction of having established in western Asia a larger measure and area of order and prosperity than that region of the earth had ever, to our knowledge, enjoyed before (270).

THE ASSYRIAN DEPORTATION POLICY

Adad Nirari I completely conquered the Mitanni and began what would become standard policy under the Assyrian Empire: the deportation of large segments of the population. With Mitanni under Assyrian control, Adad Nirari I decided the best way to prevent any future uprising was to remove the former occupants of the land and replace them with Assyrians. This should not be understood, however, as a cruel treatment of captives. Writing on this, the historian Karen Radner states,

The deportees, their labour and their abilities were extremely valuable to the Assyrian state, and their relocation was carefully planned and organised. We must not imagine treks of destitute fugitives who were easy prey for famine and disease: the deportees were meant to travel as comfortably and safely as possible in order to reach their destination in good physical shape. Whenever deportations are depicted in Assyrian imperial art, men, women and children are shown travelling in groups, often riding on vehicles or animals and never in bonds.There is no reason to doubt these depictions as Assyrian narrative art does not otherwise shy away from the graphic display of extreme violence (1).

Deportees were carefully chosen for their abilities and sent to regions which could make the most of their talents. Not everyone in the conquered populace was chosen for deportation and families were never separated. Those segments of the population that had actively resisted the Assyrians were killed or sold into slavery, but the general populaces became absorbed into the growing empire and were thought of as Assyrians. The historian Gwendolyn Leick writes of Adad Nirari I that, “the prosperity and stability of his reign allowed him to engage in ambitious building projects, building city walls and canals and restoring temples” (3). He also provided a foundation for empire upon which his successors would build.

Assyrian Archers

ASSYRIANCONQUESTOF MITANNI & THE HITTITES

His son and successor Shalmaneser I completed the destruction of the Mitanni and absorbed their culture. Shalmaneser I continued his father's policies, including the relocation of populations, but his son, Tukulti-Ninurta I (c. 1244-1208 BCE), went even further. According to Leick, Tukulti- Ninurta I “was one of the most famous Assyrian soldier kings who campaigned incessantly to maintain Assyrian possessions and influence. He reacted with spectacular cruelty to any sign of revolt” (177).He was also very interested in acquiring and preserving the knowledge and cultures of the peoples he conquered and developed a more sophisticated method of choosing which sort of individual, or community, would be relocated and to which specific location. Scribes and scholars, for example, were chosen carefully and sent to urban centers where they could help catalogue written works and help with the bureaucracy of the empire. A literate man, he composed the epic poem chronicling his victory over the Kassite king of Babylon and subjugation of that city and the areas under its influence and wrote another on his victory over the Elamites. He defeated the Hittites at the Battle of Nihriya in c. 1245 BCE which effectively ended Hittite power in the region and began the decline of their civilization . When Babylon made incursions into Assyrian territory, Tukulti-Ninurta I punished the city severely by sacking it, plundering the sacred temples, and carrying the king and a portion of the populace back to Assur as slaves. With his plundered wealth, he renovated his grand palace in the city he had built across from Assur, which he named Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, to which he seems to have retreated once the tide of popular opinion turned against him. His desecration of the temples of Babylon was seen as an offense against the gods (as the Assyrians and Babylonians shared many of the same deities) and his sons and court officials rebelled against him for putting his hand on the goods of the gods. He was assassinated in his palace, probably by one of his sons, Ashur-Nadin-Apli, who then took the throne.

TIGLATH PILESER I& REVITALIZATION

Following the death of Tukulti-Ninurta I, the Assyrian Empire fell into a period of stasis in which it neither expanded nor declined. While the whole of the Near East fell into a 'dark age' following the so-called Bronze Age Collapse of c. 1200 BCE, Ashur and its empire remained relatively intact. Unlike other civilizations in the region which suffered a complete collapse, the Assyrians seem to have experienced something closer to simply a loss of forward momentum. The empire certainly cannot be said to have 'stagnated', because the culture, including the emphasis on military campaign and the value of conquest, continued; however, there was no significant expansion of the empire and civilization as it was under Tukulti-Ninurta I.

This all changed with the rise of Tiglath Pileser I to the throne (reigned c. 1115-1076 BCE). According to Leick:

He was one of the most important Assyrian kings of this period, largely because of his wide-ranging military campaigns, his enthusiasm for building projects, and his interest in cuneiform tablet collections. He campaigned widely in Anatolia, where he subjugated numerous peoples, and ventured as far as the Mediterranean Sea. In the capital city, Assur, he built a new palace and established a library, which held numerous tablets on all kinds of scholarly subjects. He also issued a legal decree, the so-called Middle Assyrian Laws, and wrote the first royal annals. He was also one of the first Assyrian kings to commission parks and gardens stocked with foreign and native trees and plants (171).

Tiglath Pileser I

Tiglath Pileser I revitalized the economy and the military through his campaigns, adding more resources and skilled populations to the Assyrian Empire. Literacy and the arts flourished, and the preservation initiative the king took regarding cuneiform tablets would serve as the model for the later ruler, Ashurbanipal ’s, famous library at Nineveh . Upon Tiglath Pileser I's death, his son, Asharid-apal-ekur, took the throne and reigned for two years during which time he continued his father's policies without alteration. He was succeeded by his brother Ashur-bel-Kala who initially reigned successfully until challenged by a usurper who threw the empire into civil war. Although the rebellion was crushed and the participants executed, the turmoil allowed certain regions that had been tightly held by Assyria to break free and among these was the area known as Eber Nari (modern day Syria , Lebanon, and Israel ), which had been particularly important to the empire because of the well-established sea ports along the coast. The Aramaeans now held Eber Nari and began making incursions from there into the rest of the empire. At this same time, the Amorites of Babylon and the city of Mari asserted themselves and tried to break the hold of the empire. The kings who followed Ashur-bel-Kala (among them, Shalmaneser II and Tiglath Pileser II) managed to maintain the core of the empire around Ashur but were unsuccessful in re-taking Eber Nari or driving the Aramaeans and Amorites completely from the borders. The empire steadily shrank through repeated attacks from outside and rebellions from within and, with no king strong enough to revitalize the military, Assyria again entered a period of stasis in which they held what they could of the empire together but could do nothing else.

THE NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE

The Late Empire (also known as the Neo-Assyrian Empire) is the one most familiar to students of ancient history as it is the period of the largest expansion of the empire. It is also the era which most decisively gives the Assyrian Empire the reputation it has for ruthlessness and cruelty. The historian Kriwaczek writes:

Assyria must surely have among the worst press notices of any state in history. Babylon may be a byname for corruption, decadence and sin but the Assyrians and their famous rulers, with terrifying names like Shalmaneser, Tiglath-Pileser , Sennacherib , Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, rate in the popular imagination just below Adolf Hitler and Genghis Khan for cruelty, violence, and sheer murderous savagery (208).

This reputation is further noted by the historian Simon Anglim and others. Anglim writes:

While historians tend to shy away from analogies, it is tempting to see the Assyrian Empire, which dominated the Middle East from 900-612 BC, as a historical forebear of Nazi Germany: an aggressive, murderously vindictive regime supported by a magnificent and successful war machine. As with the German army of World War II, the Assyrian army was the most technologically and doctrinally advanced of its day and was a model for others for generations afterwards. The Assyrians were the first to make extensive use of iron weaponry [and] not only were iron weapons superior to bronze, but could be mass-produced, allowing the equipping of very large armies indeed (12).

While the reputation for decisive, ruthless, military tactics is understandable, the comparison with the Nazi regime is less so.Unlike the Nazis, the Assyrians treated the conquered people they relocated well (as already addressed above) and considered them Assyrians once they had submitted to central authority. There was no concept of a 'master race' in Assyrian policies; everyone was considered an asset to the empire whether they were born Assyrian or were assimilated into the culture. Kriwaczek notes, “In truth, Assyrian warfare was no more savage than that of other contemporary states. Nor, indeed, were the Assyrians notably crueler than the Romans, who made a point of lining their roads with thousands of victims of crucifixion dying in agony” (209). The only fair comparison between Germany in WWII and the Assyrians, then, is the efficiency of the military and the size of the army, and this same comparison could be made with ancient Rome .

These massive armies still lay in the future, however, when the first king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire came to power. The rise of the king Adad Nirari II (c. 912-891 BCE) brought the kind of revival Assyria needed. Adad Nirari II re-conquered the lands which had been lost, including Eber Nari, and secured the borders. The defeated Aramaeans were executed or deported to regions within the heartland of Assyria. He also conquered Babylon but, learning from the mistakes of the past, refused to plunder the city and, instead, entered into a peace agreement with the king in which they married each other's daughters and pledged mutual loyalty. Their treaty would secure Babylon as a powerful ally, instead of a perennial problem, for the next 80 years.

Assyrian Soldiers

MILITARY EXPANSION & THE NEW VIEW OF THE GOD

The kings who followed Adad Nirari II continued the same policies and military expansion. Tukulti Ninurta II (891-884 BCE) expanded the empire to the north and gained further territory toward the south in Anatolia, while Ashurnasirpal II (884-859 BCE) consolidated rule in the Levant and extended Assyrian rule through Canaan . Their most common method of conquest was through siege warfare which would begin with a brutal assault on the city. Anglim writes:

More than anything else, the Assyrian army excelled at siege warfare, and was probably the first force to carry a separate corps of engineers…Assault was their principal tactic against the heavily fortified cities of the Near East. They developed a great variety of methods for breaching enemy walls: sappers were employed to undermine walls or to light fires underneath wooden gates, and ramps were thrown up to allow men to go over the ramparts or to attempt a breach on the upper section of wall where it was the least thick. Mobile ladders allowed attackers to cross moats and quickly assault any point in defences. These operations were covered by masses of archers, who were the core of the infantry. But the pride of the Assyrian siege train were their engines.These were multistoried wooden towers with four wheels and a turret on top and one, or at times two, battering rams at the base (186).

Advancements in military technology were not the only, or even the primary, contribution of the Assyrians as, during this same time, they made significant progress in medicine, building on the foundation of the Sumerians and drawing on the knowledge and talents of those who had been conquered and assimilated. Ashurnasirpal II made the first systematic lists of plants and animals in the empire and brought scribes with him on campaign to record new finds. Schools were established throughout the empire but were only for the sons of the wealthy and nobility. Women were not allowed to attend school or hold positions of authority even though, earlier in Mesopotamia, women had enjoyed almost equal rights. The decline in women's rights correlates to the rise of Assyrian monotheism. As the Assyrian armies campaigned throughout the land, their god Ashur went with them but, as Ashur was previously linked with the temple of that city and had only been worshipped there, a new way of imagining the god became necessary in order to continue that worship in other locales. Kriwaczek writes:

One might pray to Ashur not only in his own temple in his own city, but anywhere. As the Assyrian empire expanded its borders, Ashur was encountered in even the most distant places. From faith in an omnipresent god to belief in a single god is not a long step. Since He was everywhere, people came to understand that, in some sense, local divinities were just different manifestations of the same Ashur (231).

This unity of vision of a supreme deity helped to further unify the regions of the empire. The different gods of the conquered peoples, and their various religious practices, became absorbed into the worship of Ashur, who was recognized as the one true god who had been called different names by different people in the past but who now was clearly known and could be properly worshipped as the universal deity. Regarding this, Kriwaczek writes:

Belief in the transcendence rather than immanence of the divine had important consequences. Nature came to be desacralized, deconsecrated. Since the gods were outside and above nature, humanity – according to Mesopotamian belief created in the likeness of the gods and as servant to the gods – must be outside and above nature too. Rather than an integral part of the natural earth, the human race was now her superior and her ruler.The new attitude was later summed up in Genesis 1:26: `And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let him have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth' That is all very well for men, explicitly singled out in that passage. But for women it poses an insurmountable difficulty. While males can delude themselves and each other that they are outside, above, and superior to nature, women cannot so distance themselves, for their physiology makes them clearly and obviously part of the natural world…It is no accident that even today those religions that put most emphasis on God's utter transcendence and the impossibility even to imagine His reality should relegate women to a lower rung of existence, their participation in public religious worship only grudgingly permitted, if at all (229-230).

The Assyrian culture became increasingly cohesive with the expansion of the empire, the new understanding of the deity, and the assimilation of the people from the conquered regions. Shalmaneser III (859-824 BCE) expanded the empire up through the coast of the Mediterranean and received tribute from the wealthy Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon . He also defeated the Armenian kingdom of Urartu which had long proved a significant nuisance to the Assyrians. Following his reign, however, the empire erupted in civil war as the king Shamshi Adad V (824-811 BCE) fought with his brother for control. Although the rebellion was put down, expansion of the empire halted after Shalmaneser III. The regent Shammuramat (also famously known as Semiramis who became the mythical goddess-queen of the Assyrians in later tradition) held the throne for her young son Adad Nirari III from c. 811-806 BCE and, in that time, secured the borders of the empire and organized successful campaigns to put down the Medes and other troublesome populaces in the north. When her son came of age, she was able to hand him a stable and sizeable empire which Adad Nirari III then expanded further. Following his reign, however, his successors preferred to rest on the accomplishments of others and the empire entered another period of stagnation. This was especially detrimental to the military which languished under kings like Ashur Dan III and Ashur Nirari V.

THE GREAT KINGS OF THE NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE

The empire was revitalized by Tiglath Pileser III (745-727 BCE) who reorganized the military and restructured the bureaucracy of the government. According to Anglim, Tiglath Pileser III “carried out extensive reforms of the army, reasserted central control over the empire, reconquered the Mediterranean seaboard, and even subjugated Babylon. He replaced conscription [in the military] with a manpower levy imposed on each province and also demanded contingents from vassal states” (14). He defeated the kingdom of Uratu, which had long troubled Assyrian rulers, and subjugated the region of Syria. Under Tiglath Pileser III's reign, the Assyrian army became the most effective military force in history up until that time and would provide a model for future armies in organization, tactics, training, and efficiency.

King Tiglath-pileser III

Tiglath Pileser III was followed by Shalmaneser V (727-722 BCE) who continued the king's policies, and his successor, Sargon II (722-705 BCE) improved upon them and expanded the empire further. Even though Sargon II's rule was contested by nobles, who claimed he had seized the throne illegally, he maintained the cohesion of the empire. Following Tiglath Pileser III's lead, Sargon II was able to bring the empire to its greatest height. He was followed by Sennacherib (705-681 BCE) who campaigned widely and ruthlessly, conquering Israel, Judah, and the Greek provinces in Anatolia. His sack of Jerusalem is detailed on the 'Taylor Prism', a cuneiform block describing Sennacherib's military exploits which was discovered in 1830 CE by Britain ’s Colonel Taylor, in which he claims to have captured 46 cities and trapped the people of Jerusalem inside the city until he overwhelmed them. His account is contested, however, by the version of events described in the biblical book of II Kings, chapters 18-19, where it is claimed that Jerusalem was saved by divine intervention and Sennacherib's army was driven from the field. The biblical account does relate the Assyrian conquest of the region, however.

Sennacherib's military victories increased the wealth of the empire. He moved the capital to Nineveh and built what was known as “the Palace without a Rival”. He beautified and improved upon the city's original structure, planting orchards and gardens. The historian Christopher Scarre writes,

Sennacherib's palace had all the usual accoutrements of a major Assyrian residence: colossal guardian figures and impressively carved stone reliefs (over 2,000 sculptured slabs in 71 rooms). Its gardens, too, were exceptional. Recent research by British Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley has suggested that these were the famous Hanging Gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Later writers placed the Hanging Gardens at Babylon, but extensive research has failed to find any trace of them. Sennacherib's proud account of the palace gardens he created at Nineveh fits that of the Hanging Gardens in several significant details (231).

Ignoring the lessons of the past, however, and not content with his great wealth and the luxury of the city, Sennacherib drove his army against Babylon, sacked it, and looted the temples. As earlier in history, the looting and destruction of the temples of Babylon was seen as the height of sacrilege by the people of the region and also by Sennacherib's sons who assassinated him in his palace at Nineveh in order to placate the wrath of the gods. Although they certainly would have been motivated to murder their father for the throne (after he chose his youngest son, Esarhaddon, as heir in 683 BCE, snubbing them) they would have needed a legitimate reason to do so; and the destruction of Babylon provided them with one.

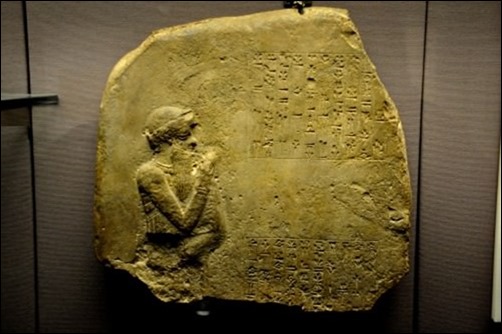

Stone Monument of Esarhaddon

His son Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) took the throne, and one of his first projects was to rebuild Babylon. He issued an official proclamation which claimed that Babylon had been destroyed by the will of the gods owing to the city's wickedness and lack of respect for the divine. Nowhere in his proclamation does it mention Sennacherib or his role in the destruction of the city but makes clear that the gods chose Esarhaddon as the divine means for restoration: “Once during a previous ruler's reign there were bad omens. The city insulted its gods and was destroyed at their command. They chose me, Esarhaddon, to restore everything to its rightful place, to calm their anger, and soothe their rage.” The empire flourished under his reign. He successfully conquered Egypt (which Sennacherib had tried and failed to do) and established the empire's borders as far north as the Zagros Mountains (modern day Iran) and as far south as Nubia (modern Sudan) with a span from west to east of the Levant (modern day Lebanon to Israel) through Anatolia (Turkey). His successful campaigns, and careful maintenance of the government, provided the stability for advances in medicine, literacy, mathematics, astronomy, architecture, and the arts. Durant writes:

In the field of art, Assyria equaled her preceptor Babylonia and in bas-relief surpassed her. Stimulated by the influx of wealth into Ashur, Kalakh, and Nineveh, artists and artisans began to produce – for nobles and their ladies, for kings and palaces, for priests and temples – jewels of every description, cast metal as skilfully designed and finely wrought as on the great gates at Balawat, and luxurious furniture of richly carved and costly woods strengthened with metal and inlaid with gold , silver , bronze, or precious stones (278).

In order to secure the peace, Esarhaddon's mother, Zakutu (also known as Naqia-Zakutu) entered into vassal treaties with the Persians and the Medes requiring them to submit in advance to his successor. This treaty, known as the Loyalty Treaty of Naqia-Zakutu, ensured the easy transition of power when Esarhaddon died preparing to campaign against the Nubians and rule passed to the last great Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE). Ashurbanipal was the most literate of the Assyrian rulers and is probably best known in the modern day for the vast library he collected at his palace at Nineveh. Though a great patron of the arts and culture, Ashurbanipal could be just as ruthless as his predecessors in securing the empire and intimidating his enemies. Kriwaczek writes, “Which other imperialist would, like Ashurbanipal, have commissioned a sculpture for his palace with decoration showing him and his wife banqueting in their garden, with the struck-off head and severed hand of the King of Elam dangling from trees on either side, like ghastly Christmas baubles or strange fruit?” (208). He decisively defeated the Elamites and expanded the empire further to the east and north. Recognizing the importance of preserving the past, he then sent envoys to every point in the lands under his control and had them retrieve or copy the books of that city or town, bringing all back to Nineveh for the royal library.

Ashurbanipal ruled over the empire for 42 years and, in that time, campaigned successfully and ruled efficiently. The empire had grown too large, however, and the regions were overtaxed. Further, the vastness of the Assyrian domain made it difficult to defend the borders. As great in number as the army remained, there were not enough men to keep garrisoned at every significant fort or outpost. When Ashurbanipal died in 627 BCE, the empire began to fall apart. His successors Ashur-etli-Ilani and Sin-Shar-Ishkun were unable to hold the territories together and regions began to break away. The rule of the Assyrian Empire was seen as overly harsh by its subjects, in spite of whatever advancements and luxuries being an Assyrian citizen may have provided, and former vassal states rose in revolt.

King Ashurbanipal

In 612 BCE Nineveh was sacked and burned by a coalition of Babylonians, Persians, Medes, and Scythians, among others. The destruction of the palace brought the flaming walls down on the library of Ashurbanipal and, although it was far from the intention, preserved the great library, and the history of the Assyrians, by baking hard and burying the clay tablet books. Kriwaczek writes, “Thus did Assyria's enemies ultimately fail to achieve their aim when they razed Ashur and Nineveh in 612 BCE, only fifteen years after Ashurbanipal's death: the wiping out of Assyria's place in history” (255). Still, the destruction of the great Assyrian cities was so complete that, within two generations of the empire's fall, no one knew where the cities had been. The ruins of Nineveh were covered by the sands and lay buried for the next 2,000 years.

LEGACY OF ASSYRIA

Thanks to the Greek historian Herodotus , who considered the whole of Mesopotamia 'Assyria', scholars have long known the culture existed (as compared to the Sumerians who were unknown to scholarship until the 19th century CE). Mesopotamian scholarship was traditionally known as Assyriology until relatively recently (though that term is certainly still in use), because the Assyrians were so well known through the primary sources of the Greek and Roman writers. Through the expanse of their empire, the Assyrians spread Mesopotamian culture to the other regions of the world, which have, in turn, impacted cultures world-wide up to the present day. Durant writes:

Through Assyria's conquest of Babylon, her appropriation of the ancient city's culture, and her dissemination of that culture throughout her wide empire; through the long Captivity of the Jews, and the great influence upon them of Babylonian life and thought; through the Persian and Greek conquests which then opened with unprecedented fullness and freedom all the roads of communication and trade between Babylon and the rising cities of Ionia , Asia Minor, and Greece – through these and many other ways the civilization of the Land between the Rivers passed down into the cultural endowment of our race. In the end nothing is lost; for good or evil, every event has effects forever (264).

Tiglath Pileser III had introduced Aramaic to replace Akkadian as the lingua franca of the empire and, as Aramaic survived as a written language, this allowed later scholars to decipher Akkadian writings and then Sumerian. The Assyrian conquest of Mesopotamia, and the expansion of the empire throughout the Near East, brought Aramaic to regions as near as Israel and as far as Greece and, in this way, Mesopotamian thought became infused with those cultures and a part of their literary and cultural heritage. Following the decline and rupture of the Assyrian empire, Babylon assumed supremacy in the region from 605-549 BCE. Babylon then fell to the Persians under Cyrus the Great who founded the Achaemenid Empire (549-330 BCE) which fell to Alexander the Great and, after his death, was part of the Seleucid Empire .

The region of Mesopotamia corresponding to modern-day Iraq, Syria, and part of Turkey was the area at this time known as Assyria and, when the Seleucids were driven out by the Parthians, the western section of the region, formerly known as Eber Nari and then Aramea, retained the name Syria. The Parthians gained control of the region and held it until the coming of Rome in 115 CE, and then the Sassanid Empire held supremacy in the area from 226-650 CE until, with the rise of Islam and the Arabian conquests of the 7th century CE, Assyria ceased to exist as a national entity. Among the greatest of their achievements, however, was the Aramaic alphabet , imported into the Assyrian government by Tiglath Pileser III from the conquered region of Syria. Aramaean was easier to write than Akkadian and so older documents collected by kings such as Ashurbanipal were translated from Akkadian into Aramaic, while newer ones were written in Aramaic and ignored the Akkadian. The result was that thousands of years of history and culture were preserved for future generations, and this is the greatest of Assyria's legacies.

Studying History & Evaluating Sources › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Emma Groeneveld

History (from the Greek ἱστορία, meaning 'a learning or knowing by inquiry') can be broadly taken to indicate the past in general but is usually defined as the study of the past from the point at which there were written sources onwards.

There are obstacles that make it so we do not have a crystal clear, uninterrupted view of the past. Firstly, we have to remember that everyone – not just us, but also people throughout history – is shaped by their upbringing and the societies and times they live in, and we need to be careful not to stick our own labels and values onto past periods. Secondly, our view of the past is made up from the total of things that somehow happened to survive the test of time, which is due to coincidences and decisions made by people before our time. So, we only get a fragmentary, distorted view; it is like trying to complete a puzzle with a lot of oddly shaped and missing pieces.

THE ART OF WAR BY SUN-TZU

To fill in the context of the past we wish to study involves carefully questioning a whole bunch of sources – not just written ones – and avoiding pitfalls as much as possible. The closely connected field of archaeology offers a priceless helping hand in achieving this, so these sources will be discussed here, too.

UNRAVELLING THE SOURCES

WE ONLY GET A FRAGMENTARY, DISTORTED VIEW; IT IS LIKE TRYING TO COMPLETE A PUZZLE WITH A LOT OF ODDLY SHAPED & MISSING PIECES.

Sources are our way of peering into the past, but the various kinds all present their own benefits and difficulties. The first distinction to make is between primary and secondary sources. A primary source is first-hand material that stems (roughly) from the time period that one wants to examine, whereas a secondary source is an additional step removed from that period – a 'second-hand' work that is the result of reconstructing and interpreting the past using the primary material, such as textbooks, articles, and, of course, websites such as this one.

PRIMARY SOURCES

However cool actual sources from times gone by may be, we cannot simply assume that everything they tell us (or everything we think they tell us) is true, or that we are automatically able to interpret their contents and context correctly. They were made by people, from within their own contexts. Keeping a critical eye and asking questions is thus the way to go, and it is a good idea to cross-examine different sources on the same topic to see whether any kind of consensus rolls out.

Some general questions you should ask of any type of source are:

• What type of source is it? What does its form tell us? Is it a neatly engraved inscription, an undecorated, heavily used bit of earthenware, or a roughly scribbled letter on cheap paper?

• Who created the source? How did they gather the necessary information? Were they an eyewitness, or did they rely on researching other sources or on the stories of people who had witnessed the event? Could they be biased?

• With which goal was the source created? Did the creator want to tell a truthful story or, for instance, influence others through propaganda? How reliable does that make it?

• What is the context in which the source was created? To understand a source it helps to know something about the society and immediate context in which it was made. A Christian source written while Christianity was still a persecuted religiondiffers from one after Christianity was made the official religion. Compare it with other sources from the same period/that concern the same subject to help you assess how reliable the source may be and help you interpret its content.

• What is the content of the source and how do we interpret it? What does it tell us and what does it not tell us? What are its limitations? What sorts of questions could this source answer?

Different sources bring different benefits and pitfalls with them, though; these will be discussed in more detail below.

WRITTEN SOURCES

Some examples of primary written sources are contemporary letters, eyewitness accounts, official documents, political declarations and decrees, administrative texts, and histories and biographies written in the period that is to be studied.

Benefits – details; personal side; context

The unmatched level of detail presented by written sources in general is an obvious goldmine to the greedy historian.Moreover, reading a written source tends to tell you something about the author and the context in which they are writing just as well as the topic they concern themselves with.

The detail in some written sources can lead to unexpected discoveries, such as the astonishing fact that the Phoeniciansalready sailed around Cape of Good Hope (South Africa) in open boats as early as 600 BCE. Herodotus , the 'father of history', writes in his Histories – a work recounting the events of the Greco- Persian Wars (499-479 BCE) – that

On their return, they declared - I for my part do not believe them, but perhaps others may - that in sailing round Libya [Africa] they had the sun upon their right hand. In this way was the extent of Libya first discovered. (Hdt. IV. 42).

South of the equator, the sun would indeed have been on the sailors' right-hand side while sailing westward around the Cape – a detail the sailors could not have known if they had not actually witnessed it, so it appears to be true.

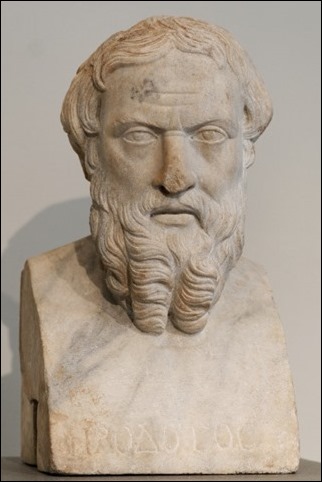

Herodotus

Pitfalls – transmission; reliability, bias & intentions; contemporaneity

The first hurdle with written sources is their transmission; materials such as papyrus, parchment, and paper do not have infinite lifespans, so the sources we have in front of us right now have usually been copied, reviewed, edited, even translated, at some point in time, and may include mistakes or deliberate changes. This puts a thin barrier between us and the original text.

Secondly, authors may not be reliable, may have been biased, or may have had certain intentions that jeopardise the source's objectivity. Forgery is unfortunately also not entirely outside the realm of possibilities, as the Donatio Constantini (the Donation of Constantine ) makes painfully clear. Asking the following questions can help canvass these issues:

• Who created the source and what was his or her background?

People are undeniably connected with their backgrounds – upbringing, family, the times they lived in, and so forth, and we have to examine the source from within this framework.

• What do we know of the context in which the source was created?

The prevailing values, schools of thought, religion, the political situation, possible censure, as well as whether the source was perhaps commissioned by someone or not, all have an impact on the contents of a source. Comparing a source to other (types of) sources from the same period or concerning the same topic can help determine its reliability and help you form a picture of what may have actually happened.

• Did the creator have a specific goal or a specific audience?

A personal letter with the goal of declaring the author's love to his recipient yields a different kind of information than a piece of propaganda written in order to strengthen a ruler's position. Of course, the goal may not be quite as easy to spot as that.

Thirdly, it is important to check whether the author was actually around for the events they are writing about. Questions to ask are:

• Was the author a contemporary and/or an eyewitness?

• If no: where did they get their information and how reliable was that information? It could have come from documents, eyewitnesses, or other sources available to them.

• If yes: did they personally witness the event they are describing? How accurate is their memory? Being alive at the same time as Empress Wu from Song China , for instance, does not automatically mean you were in a position to see which clothes she wore on a specific Monday morning.

Herodotus, for instance, was not an eyewitness himself, and although usually of decent critical mind, he sometimes fell flat in his judgement of his sources - the person who convinced him that the hind legs of camels have four thigh bones and four knee-joints must have been well chuffed. (Hdt. III.103). Furthermore, when entire speeches are recorded word-for-word, one must wonder how plausible it is, firstly, that the eyewitness remembered all of it, sometimes for a long stretch of time, and, secondly, that the author then recorded the whole speech exactly as recited by his witness, without shaping it to suit his desired narrative.

EPIGRAPHY

Epigraphy refers to the study of inscriptions engraved upon various surfaces such as stone, metal, wood, clay tablets, or even wax, which may vary hugely in length from mere abbreviated words and administrative tablets to depicting entire official decrees.

Benefits – typically durable; visible

Usually, inscriptions tend to be pretty durable because of the nature of the materials that were used, although whether or not the inscription has been exposed to the elements makes a bit of a difference. They were often intended to be publically visible, catching the eye like a big neon sign, their content shared with as many people as possible.

Pitfalls – audience; creators; intentions

This often public nature does not mean inscriptions should just be mindlessly accepted to reflect the exact truth, though; they had authors or commissioners who had certain purposes. Sometimes inscriptions even turn out to be forged, or have been moved and are no longer in their original locations. Things to keep in mind are:

• Who created or commissioned the inscription?

Is this, for instance, a lonely mother who had an elaborate, glorifying, and soppy inscription engraved on the headstone of her young son's grave , for passers-by to see, or is it a ruler's proclamation which subtly connects himself with a divine power?

• What is the goal of the inscription?

Perhaps it was created to inform, to record, to glorify, or to influence public opinion.

• Can it be dated (by things like the context, monument, or the language), and does the date match the content of the inscription?

Pantheon Front, Rome

A good example of the sometimes misleading nature of inscriptions is the Pantheon in Rome , a sometimes infuriating structure to go look at when you come too close to tourist groups led by guides that are not aware of the full story. The inscription states the following:

M(arcus) A(grippa) L(ucius) F(ilius) Co(n)s(ul) Tertium Fecit – ('Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, three times consul , made this')

Upon deciphering this text – the abbreviations are standardised ones routinely used in inscriptions in Ancient Rome – one would conclude that the building was created by Marcus Agrippa, emperor Augustus ' right-hand man. However, the buildings' bricks were stamped with the names of the consuls in office at the time of firing, which has allowed us to date the whole thing to a good century and a half later than Agrippa, belonging instead to the first part of emperor Hadrian ’s reign, probably between 117-126-8 CE. The good man wanted to honour an earlier building at the same site, which was built by Agrippa around 25 BCE, and decided to stick Agrippa's inscription on his own brand-new entablature. There is thus more than meets the eye.

SETTLEMENTS, BUILDINGS, & MONUMENTS

Benefits – made to last; indicate structure of societies

The daily lives of people become visible through the remains of their houses and the buildings they made use of, such as courts of law, bakeries, or schools. Monuments, also not unusually flashing inscriptions at its audience, can reveal the messages their normally powerful creators cried out to the world through their architecture and imagery. As such, they can be used to reconstruct the structure of societies.

Pitfalls – not always well-preserved; inferring meaning; propaganda

Of course, the actual durability varies immensely, and sometimes not much more than the groundworks remain. We must thus ask:

• How do we accurately reconstruct the remains (physically or on paper)?

Archaeologists have become quite adept at 'reading' the pieces that are left; comparing the remains with others that may be more fully preserved or with primary sources describing the structure; and rebuilding what is essentially a hugely complex 3D puzzle, either on paper or by actually restoring the remains in question. Bits and pieces may have been carted off, destroyed, moved around, fallen over, and so forth, so it is important to keep in mind that the puzzle process may require some guesswork and may result in mistakes being made.

• What is the function of the structure?

• How do we interpret what it may tell us about a culture?

The site of Palenque – an important Maya city situated in present-day Mexico – for instance, is home to a group of temples that fit within a context of both propaganda and symbolism. The Temples of the Cross, Foliated Cross, and Sun, dedicated in 692 CE, were commissioned by king Kan Balam. Their sculptures and reliefs illustrate the king's connection with the gods: he is depicted as a guardian of fertility, maize, and rain.

Kan Balam moreover legitimised his rule by depicting his genealogy as well as a scene in which he receives his power from his ancestors. More practically, these temples were important ceremonial centres too. At this site, the political is thus visibly linked with the ritual context – something that fits well within the broader Mayan cultural context – and, as a source, it must be interpreted within this framework.

Temple of the Sun, Palenque

ARTEFACTS

Benefits – daily lives; use; society & culture

Pitfalls – inferring meaning; inferring clues about society

Artefacts are man-made things of archaeological interest, often from a cultural context. Examples are pottery , utensils, tools and jewellery, which can alert us to daily lives, style and culture; art – including statues – which can be both public and private and reflects the society in some way; and coins, which are more political - often standardised, they proclaim a visible message that tends to serve as propaganda to bolster a ruler's image. We should ask of each artefact:

• What was its use or purpose?

• What might it tell us about the society's structure and culture?

An example lies within the 15th- and 16th-century CE Korean Buncheong wares – practically used ceramics that were blue-green with a white slip, typically decorated with combinations of geometric and natural shapes such as peonies, birds and fish, enhanced with dots. They are interesting not just because of their homely context and the light they shed on daily lives but also because they were produced by potteries that were not controlled by the state – in contrast to other types of Korean pottery .This means that Buncheong wares show a lot of regional flavour and out-of-the-box variation, as well as showing the preferences of the people who ordered the wares. This helps us colour in the lives and homes of ordinary Koreans living at that time.

Korean Buncheong Bottle

BONES

Benefits – morphology; health & related clues; filling in blanks; genetic evidence

Studying bones yields clues regarding health, gender, age, size, diet, etc. Retrieval of ancient DNA – though not exactly a walk in the park – is also possible. The context in which bones are found as well as the point in time they came from help to fill information regarding their societies. This is already valuable in support of historical sources, as, for instance, mass graves of victims of the black death support the image created by the written record, but for the prehistoric side of things, bones are truly indispensable in helping us fill in the blanks.

For places such as Australia, we have no written sources until westerners came brutally barging in in 1788 CE. Here, bones can alert us to the prehistoric human presence in specific areas. For instance, through tracing bones found at sites such as Malakunanja 2 in Australia's Northern Territory, dated to around 53,000 years old, and the famous Lake Mungo burials in southern Australia dated to around 41,000 years old, we can fill in Australia's initial colonisation.

Pitfalls – dating; interpretation context

Dating bones is not always a straightforward matter, though. Things to keep in mind are:

• Is the dating scientifically and/or archaeologically accurate? Could there be contamination, could sediments have shifted or could the bones have been moved?

• How should the context in which the bones were found be interpreted? What does the context tell you about the bones themselves?

SECONDARY SOURCES

After the maze that is primary sources, we may be tempted to think secondary sources are a sort of safe haven, where skilled researchers have taken all of the above-mentioned issues into account and have already come as close to actual history as possible.

However, this would be a tad naïve; the people writing the secondary material are just as bound to their own contexts as the ancients they are studying. Again, then, we must be wary of possible bias and goals, as well as of the accuracy – it is all too easy to draw conclusions that support your hypothesis. Even if a secondary source may appear reliable in that it shows you which sources they have used and seems to draw logical conclusions from them, it is still possible that the author has hand-picked exactly those sources that support their story, rather than presenting the full picture (which may contradict or add more nuance to their story). To prevent being misled, it is important to always study more than one secondary sources. Compare different books and articles on the subject you are researching, and, after assessing each source's reliability, strengths and weaknesses, try to get as complete a view as possible of the topic.

When using secondary sources, it thus helps to ask these questions:

• Has the author been trained in the right field, and does he or she have decent credit in the academic world?

Reading reviews can be of great assistance here.

• Where was the source published and could that impact the contents at all?

My own history education in the Netherlands was filled with many textbooks that were quite western in nature, unfortunately offering less expertise (or even interest) with regard to other areas of the world. Also, when it comes to articles, some journals have better reputations than others.

• When was the source published?

Times change. A textbook written in the 1960s CE may not have had access to all the information we have right now and may be coloured by the time's prevailing ideas about how to approach the study of history.

• What is the scope of the source?

Social histories paint a different picture than military ones, so be sure to choose sources that correspond with the questions you yourself want to answer.

• Which sources has the author used and how critical has he or she been?

It is important the author has documented his or her use of sources, so you can examine them yourself if need be. Keep an eye out for selective use of sources; an author should not simply choose the sources that fit their hypothesis but should take the full range of primary information into account.

The materials to be questioned vary from, for instance, textbooks and course books to independent books, articles (including scientific ones, whose accuracy may be hard to judge by a non-scientist), and websites – but be sure to pick ones that show source lists and authors' names. As long as you stay critical, there is a wealth of information at your disposal.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License

![clip_image003[1] clip_image003[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEipUnISw7RWWnoT1WtlBQNjktp7qqIsGYHpBFWM4JfBxiWoi5M28Lr-mAGaOM9BjRBpKaOOcBirNbkIctkbxwr7abirTjHoOlU4x_k_FMNVjnuV5hazlZ-g6el7Rwx5AU5Ois-tkD78nt0/?imgmax=800)