The Temple of Hatshepsut › Ancient Egyptian Warfare › Ancient Egyptian Writing » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- The Temple of Hatshepsut › Origins

- Ancient Egyptian Warfare › Origins

- Ancient Egyptian Writing › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

The Temple of Hatshepsut › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Among the duties of any Egyptian monarch was the construction of monumental building projects to honor the gods and preserve the memory of their reigns for eternity. These building projects were not just some grandiose gesture on the part of the king to appease the ego but were central to the foundation and development of a unified state. Building projects ensured work for the peasant farmers during the period of the Nile ’s inundation, encouraged unity through a collective effort, pride in one's contribution to the project, and provided opportunities for the expression of ma'at (harmony/balance), the central value of the culture, through communal – and national – effort.

Contrary to the view so often held, the great monuments of Egypt were not built by Hebrew slaves nor by slave labor of any kind. Skilled and unskilled Egyptian workers built the palaces, temples, pyramids, monuments, and raised the obelisks as paid workers. From the period of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) through the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) and, to a lesser extent, from the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525) through the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE) the great rulers of Egypt created some of the most impressive cities, temples, and monuments in the world and these were all created by collective Egyptian effort. Egyptologist Steven Snape, commenting on these projects, writes:

The movement of large quantities of building stone – to say nothing of massive monoliths – from their quarries to distant building sites allowed the emergence of Egypt as a state that found expression through monumental construction. (97)

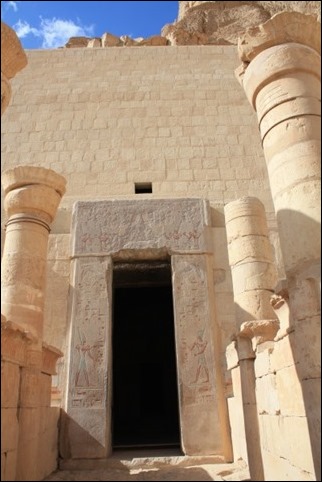

There are many examples of these great monuments and temples throughout Egypt from the pyramid complex at Giza in the north to the temple at Karnak in the south. Among these, the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) at Deir el-Bahri stands out as one of the most impressive.

Temple of Hatshepsut

The building was modeled after the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE), the great Theban prince who founded the 11th Dynasty and initiated the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE). Mentuhotep II was considered a 'second Menes ' by his contemporaries, a reference to the legendary king of the First Dynasty of Egypt, and he continued to be venerated highly throughout the rest of Egypt's history. The temple of Mentuhotep II was built during his reign across the river from Thebes at Deir el-Bahri, the first structure to be raised there. It was a completely innovative concept in that it would serve as both tomb and temple.

The king would not actually be buried in the complex but in a tomb cut into the rock of the cliffs behind it. The entire structure was designed to blend organically with the surrounding landscape and the towering cliffs and was the most striking tomb complex raised in Upper Egypt and the most elaborate created since the Old Kingdom.

Hatshepsut, an admirer of Mentuhotep II's temple had her own designed to mirror it but on a much grander scale and, just in case anyone should miss the comparison, ordered it built right next to the older temple. Hatshepsut was always keenly aware of ways in which to elevate her public image and immortalize her name; the mortuary temple achieved both ends.

It would be an homage to the 'second Menes' but, more importantly, link Hatshepsut to the grandeur of the past while, at the same time, surpassing previous monumental works in every respect. As a woman in a traditionally male position of power, Hatshepsut understood she needed to establish her authority and the legitimacy of her reign in much more obvious ways that her predecessors and the scale and elegance of her temple is evidence of this.

HATSHEPSUT'S REIGN

Hatshepsut was the daughter of Thutmose I (1520-1492 BCE) by his Great Wife Ahmose. Thutmose I also fathered Thutmose II (1492-1479 BCE) by his secondary wife Mutnofret. In keeping with Egyptian royal tradition, Thutmose II was married to Hatshepsut at some point before she was 20 years old. During this same time, Hatshepsut was elevated to the position of God's Wife of Amun, the highest honor a woman could attain in Egypt after the position of queen and one which would become increasingly political and important.

Hatshepsut and Thutmose II had a daughter, Neferu-Ra, while Thutmose II fathered a son with his lesser wife Isis. This son was Thutmose III (1458-1425 BCE) who was named his father's successor. Thutmose II died while Thutmose III was still a child and so Hatshepsut became regent, controlling the affairs of state until he came of age. In the seventh year of her regency, though, she broke with tradition and had herself crowned pharaoh of Egypt.

Portrait of Queen Hatshepsut

Her reign was one of the most prosperous and peaceful in Egypt's history. There is evidence that she commissioned military expeditions early on and she certainly kept the army at peak efficiency but, for the most part, her time as pharaoh is characterized by successful trade, a booming economy, and her many public works projects which employed laborers from across the nation.

Her expedition to Punt seems to have been legendary and was certainly the accomplishment she was most proud of, but it also seems that all of her trade initiatives were equally successful and she was able to employ an entire nation in building her monuments. These works were so beautiful and so finely crafted that they would be claimed by later kings as their own.

THE TEMPLE DESIGN & LAYOUT

She commissioned her mortuary temple at some point soon after coming to power in 1479 BCE and had it designed to tell the story of her life and reign and surpass any other in elegance and grandeur. The temple was designed by Hatshepsut's steward and confidante Senenmut, who was also tutor to Neferu-Ra and, possibly, Hatshepsut's lover. Senenmut modeled it carefully on that of Mentuhotep II but took every aspect of the earlier building and made it larger, longer, and more elaborate.Mentuhotep II's temple featured a large stone ramp from the first courtyard to the second level; Hatshepsut's second level was reached by a much longer and even more elaborate ramp one reached by passing through lush gardens and an elaborate entrance pylon flanked by towering obelisks.

Walking through the first courtyard (ground level), one could go directly through the archways on either side (which led down alleys to small ramps up to the second level) or stroll up the central ramp, whose entrance was flanked by statues of lions. On the second level, there were two reflecting pools and sphinxes lining the pathway to another ramp which brought a visitor up to the third level.

Senemut, kneeling fugure

The first, second, and third levels of the temple all featured colonnade and elaborate reliefs, paintings, and statuary. The second courtyard would house the tomb of Senenmut to the right of the ramp leading up to the third level; an appropriately opulent tomb placed beneath the second courtyard with no outward features in order to preserve symmetry. All three levels exemplified the traditional Egyptian value of symmetry and, as there was no structure to the left of the ramp, there could be no apparent tomb on its right.

On the right side of the ramp leading to the third level was the Birth Colonnade, and on the left the Punt Colonnade. The Birth Colonnade told the story of Hatshepsut's divine creation with Amun as her true father. Hatshepsut had the night of her conception inscribed on the walls relating how the god came to mate with her mother:

He [Amun] in the incarnation of the Majesty of her husband, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt [Thutmose I] found her sleeping in the beauty of her palace. She awoke at the divine fragrance and turned towards his Majesty. He went to her immediately, he was aroused by her, and he imposed his desire upon her. He allowed her to see him in his form of a god and she rejoiced at the sight of his beauty after he had come before her. His love passed into her body. The palace was flooded with divine fragrance. (van de Mieroop, 173)

As the daughter of the most powerful and popular god in Egypt at the time, Hatshepsut was claiming for herself special privilege to rule the country as a man would. She established her special relationship with Amun early on, possibly before taking the throne, in order to neutralize criticism of her reign on account of her gender.

Birth Colonnade, Hatshepsut's Temple

The Punt Colonnade related her glorious expedition to the mysterious 'land of the gods' which the Egyptians had not visited in centuries. Her ability to launch such an expedition is testimony to the wealth of the country under her rule and also her ambition in reviving the traditions and glory of the past. Punt was known to the Egyptians since the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) but either the route had been forgotten or Hatshepsut's more recent predecessors did not consider an expedition worth their time. Hatshepsut describes how her people set out on the trip, their warm reception in Punt, and makes a detailed list of the many luxury goods brought back to Egypt:

The loading of the ships very heavily with marvels of the country of Punt; all goodly fragrant woods of God's Land, heaps of myrrh-resin, with fresh myrrh trees, with ebony and pure ivory, with green gold of Emu, with cinnamon wood, Khesyt wood, with Ihmut-incense, sonter-incense, eye cosmetic, with apes, monkeys, dogs, and with skins of the southern panther. Never was brought the like of this for any king who has been since the beginning. (Lewis, 116)

At either end of the second level colonnade were two temples: The Temple of Anubis to the north and The Temple of Hathorto the south. As a woman in a position of power, Hatshepsut had a special relationship with the goddess Hathor and invoked her often. A temple to Anubis, the guardian and guide to the dead, was a common feature of any mortuary complex; one would not wish to slight the god who was responsible for leading one's soul from the tomb to the afterlife.

The ramp to the third level, centered perfectly between the Birth and Punt colonnades, brought a visitor up to another colonnade, lined with statues, and the three most significant structures: the Royal Cult Chapel, Solar Cult Chapel, and the Sanctuary of Amun. The whole temple complex was built into the cliffs of Deir el-Bahri and the Sanctuary of Amun – the most sacred area of the site – was cut from the cliff itself. The Royal Cult Chapel and Solar Cult Chapel both depicted scenes of the royal family making offerings to the gods. Amun-Ra, the composite creator/sun god, is featured prominently in the Solar Cult Chapel with Hatshepsut and her immediate family kneeling before him in honor.

DESECRATION & ERASURE FROM HISTORY

Throughout Hatshepsut's reign, Thutmose III had not been idling at court but was leading the armies of Egypt on successful campaigns of conquest. Hatshepsut had given him supreme command of the military, and he did not disappoint her.Thutmose III is considered one of the greatest military leaders in the history of ancient Egypt and the most consistently successful in the period of the New Kingdom.

THUTMOSE III HAD ALL EVIDENCE OF HER REIGN DESTROYED FROM ALL PUBLIC MONUMENTS BUT HE LEFT RELATIVELY UNTOUCHED THE STORY OF HER DIVINE BIRTH & EXPEDITION TO PUNT INSIDE HER MORTUARY TEMPLE.

In c. 1457 BCE Thutmose III led his armies to victory at the Battle of Megiddo, a campaign possibly anticipated and prepared for by Hatshepsut, and afterwards her name disappears from the historical record. Thutmose III had all evidence of her reign destroyed by erasing her name and having her image cut from all public monuments. He then backdated his reign to the death of his father and Hatshepsut's accomplishments as pharaoh were ascribed to him. Senenmut and Neferu-Ra were dead by this time, and it seems anyone else who was personally loyal to Hatshepsut lacked the power or inclination to challenge Thutmose III's policy regarding his step-mother's memory.

To erase one's name on earth was to condemn that person to non-existence. In ancient Egyptian belief, one needed to be remembered in order to continue one's eternal journey in the afterlife. Although Thutmose III seems to have ordered this extreme measure, there is no evidence of any enmity between him and his step-mother, and significantly, he left relatively untouched the story of her divine birth and expedition to Punt inside her mortuary temple; only public mention of her was erased. This would indicate that he did not harbor Hatshepsut any ill will personally but was attempting to eradicate any overt evidence of a strong female pharaoh.

The monarch of Egypt was traditionally male, in keeping with the legendary first king of Egypt, the god Osiris. Although no one knows for sure why Thutmose III chose to remove his step-mother from history, it is probably because she broke with the tradition of male rulers and he did not want women in the future emulating Hatshepsut in this way. The most vital duty of the pharaoh was the maintenance of ma'at and honoring the traditions of the past was a part of this in that it maintained balance and social stability. Even though Hatshepsut's reign had been successful, there was no way to guarantee that another woman, inspired by her example, would be able to rule as effectively. To allow the precedent of an able woman as pharaoh to stand, therefore, could have been quite threatening to Thutmose III's understanding of ma'at.

Egyptian Soldiers

Although the inner reliefs, paintings, and inscriptions of her temple were left largely intact, some were defaced by Thutmose III and others by the later pharaoh Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE). By the time of Akhenaten, Hatshepsut had been forgotten.Thutmose III had replaced her images with his own, buried her statues, and built his own mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri in between Hatshepsut's and Mentuhotep II's. His temple is much smaller than either, but this was not a concern since he essentially took over Hatshepsut's temple as his own.

Akhenaten, therefore, had no quarrel with Hatshepsut as a female pharaoh; his problem was with her god. Akhenaten is best known as the 'heretic king' who abolished the traditional religious beliefs and practices of Egypt and replaced them with his own brand of monotheism centered on the solar god Aten. Although he is routinely hailed as a visionary for this by monotheists, his action was most likely motivated far more by politics than theology. The Cult of Amun had grown so powerful by Akhenaten's time that it rivaled the throne – a problem faced by a number of kings throughout Egypt's history – and abolishing that cult along with all the others was the quickest and most effective way of restoring balance and wealth to the monarchy. Although Hatshepsut's temple (understood by Akhenaten to be that of Thutmose III) was allowed to stand, the images of Amun were cut from the exterior and interior walls.

HATSHEPSUT'S REDISCOVERY

Hatshepsut's name remained unknown for the rest of Egypt's history and up until the mid-19th century CE. When Thutmose III had her public monuments destroyed, he disposed of the wreckage near her temple at Deir el-Bahri. Excavations in the 19th century CE brought these broken monuments and statues to light but, at that time, no one understood how to read hieroglyphics – many still believed them to be simple decorations – and so her name was lost to history.

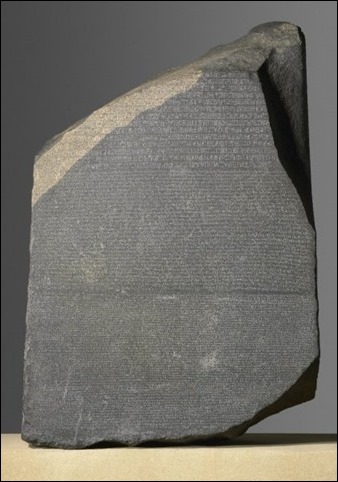

The English polymath and scholar Thomas Young (1773-1829 CE), however, was convinced that these ancient symbols represented words and that hieroglyphics were closely related to demotic and later Coptic scripts. His work was built upon by his sometimes-colleague-sometimes-rival, the French philologist and scholar Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832 CE). In 1824 CE Champollion published his translation of the Rosetta Stone, proving that the symbols were a written language and this opened up ancient Egypt to a modern world.

Champollion, visiting Hatshepsut's temple, was mystified by the obvious references to a female pharaoh during the New Kingdom of Egypt who was unknown in history. His observations were the first in the modern age to inspire an interest in the queen who, today, is regarded as one of the greatest monarchs of the ancient world.

Tomb of Hatshepsut

How and when Hatshepsut died was unknown until quite recently. She was not buried in her mortuary temple but in a tomb in the nearby Valley of the Kings (KV60). Egyptologist Zahi Hawass located her mummy in the Cairo museum's holdings in 2006 CE and proved her identity by matching a loose tooth from a box of hers to the mummy. An examination of that mummy shows that she died in her fifties from an abscess following this tooth's extraction.

Although later Egyptian rulers did not know her name, her mortuary temple and other monuments preserved her legacy. Her temple at Deir el-Bahri was considered so magnificent that later kings had their own built in the same vicinity and, as noted, were so impressed with this temple and her other works that they claimed them as their own. There is, in fact, no other Egyptian monarch except Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) who erected as many impressive monuments as Hatshepsut.Although unknown for most of history, in the past 100 years her accomplishments have achieved global recognition. In the present day, she is a commanding presence in Egyptian – and world – history and stands as the very role model for women that Thutmose III may have tried so hard to erase from time and memory.

Ancient Egyptian Warfare › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

The Narmer Palette, an ancient Egyptian cermonial engraving, depicts the great king Narmer (c. 3150 BCE) conquering his enemies with the support and approval of his gods. This piece, dating from c. 3200-3000 BCE, was initially thought to be an accurate historical depiction of the unification of Egypt under Narmer, the first king of the First Dynasty. Recent revisions in scholarship, however, now interpret the artifact as a symbolic rendering of this historical event and claim that Narmer (also known as Menes ) may or may not have united the country by force but that the concept of the king as a mighty warrior was an important cultural value and so Narmer was depicted as a conqueror.

The great kings of Mesopotamia, especially the Assyrian rulers, left behind many inscriptions of their military victories, prisoners taken, cities destroyed but for most of Egypt's early history such records do not exist. The Egyptians considered their land the most perfect in the world and were not so much interested in conquest as in preservation of what they had. The early records of Egyptian warfare all have to do with civil unrest, not conquest of other lands, and this would be the paradigm from the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-2613 BCE) until the time of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) when the kings of the 12th Dynasty maintained a standing army which they led on military campaigns beyond their borders.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF PROFESSIONAL WARFARE

Although modern day scholars disagree on whether Narmer united Egypt through conquest, there is no doubt that a military force under a strong leader was necessary to hold the country together. Throughout the First Dynastic Period there is evidence of unrest, perhaps even a division of the country at one point, and civil wars between factions fighting for the throne.

DURING THE NEW KINGDOM PERIOD EGYPT EXPANDED ITS EMPIRE & WAS CONSTANTLY AT WAR.THUTHMOSE III LED AT LEAST SEVENTEEN DIFFERENT CAMPAIGNS IN TWENTY YEARS.

Through the time of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) the central government relied on regional governors ( nomarchs ) to supply men for the army. The nomarch would conscript soldiers in their region and send them to the king. Each battalion carried standards bearing the totem of their district ( nome ) and their loyalties were with their community, their brothers-in-arms, and to their nomarch. The effectiveness of this early militia is attested to by the successful campaigns in Nubia, Syria, and Palestine of Old Kingdom monarchs to either secure the borders, quell uprisings, or seize resources for the crown. The soldiers fought for the king and their country but they were not a united Egyptian army so much as a band of smaller military units fighting for a common goal. The conscripts were often supplemented by Nubian mercenaries who had the same degree of loyalty to the king as long as they were being paid.

The rise in the power of individual nomarchs was among the contributing factors in the collapse of the Old Kingdom and the beginning of the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181-2040 BCE). The central government at Memphis was no longer relevant as each district's nomarch assumed control of their own region, built temples in their own honor instead of a king's, and used their militia for their own ends. In an attempt to regain some of their lost prestige, perhaps, the kings at Memphis moved their capital to the city of Herakleopolis, which was more centrally located. They were no more effective at the new location, however, than they had been at the old and were overthrown by Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) of Thebes who initiated the period of the Middle Kingdom.

Narmer

It is likely that Mentuhotep II led an army of conscripts from Thebes but he may have already mobilized a professional fighting force in his district. It is also entirely possible that there was a core of professional soldiers who fought for the king as far back as the Pre-Dynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 BCE) but the evidence for this is unclear. Most scholars agree that it was Mentuhotep II's successor, Amenemhat I (c. 1991-1962 BCE) who created the first standing army in Egypt. This would make a great deal of sense because it would have taken power from the individual nomarchs and placed it in the hands of the king.The king now had direct control of an army which was loyal to him and the country as a whole, not to different nomarchs and their regions.

ARMIES & WEAPONS IN THE OLD KINGDOM

The weapons of the Pre-Dynastic and Early Dynastic Periods were primarily maces, daggers, and spears. By the time of the Old Kingdom the bow and arrow, among other weaponry, had been added as historian Margaret Bunson explains:

The soldiers of the Old Kingdom were depicted as wearing skull caps and carrying clan or nome-totems. They used maces with wooden heads or pear-shaped stone heads. Bows and arrows were standard gear, with square-tipped flint arrowheads and leather quivers. Some shields, made of hides, were in use but not generally.Most of the troops were barefoot, dressed in simple kilts, or naked (168).

The Egyptians used a simple single-arched bow which was hard to draw, had a short range, and unreliable accuracy. The soldiers were all from the lower-class peasantry population and had little training. It is unlikely, though possible, that they would have had experience with a bow in hunting. The peasantry owned no land in Egypt and hunting was prohibited without the consent of the upper-class landowner. Further, the Egyptian diet was mostly vegetarian and hunting was a sport of royalty.Still, with archers firing en masse from a close position, these weapons could be very effective. After a volley or two of arrows, the soldiers would close with their opponents using hand weapons. The Egyptian navy at this time was used only to transport troops, not for enemy engagement.

![clip_image005 [1] clip_image005 [1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjSMbq3lcXj6dvskNCsTvKlSG3kTdTLruQJcUPBUsInPERhQMCaSTGEE2PC31pcLUuu3l0CPb82sd6JxCOrtIwvvYe2zx07szmeNAXlMt-UPcamz5HbFN0e30EeSp-LPkvz9WvAVpoXjis/?imgmax=800)

Egyptian Soldiers

MIDDLE KINGDOM WARFARE

By the time of the Middle Kingdom the troops carried copper axes and swords. The long, bronze spear became standard as did body armor of leather over short kilts. The army was better organized with "a minister of war and a commander in chief of the army, or an official who worked in that capacity" (Bunson, 169). These professional troops were highly trained and there were elite "shock troops" used as the vanguard. Officers were in charge of an unspecified number of men in their units and reported to a commander who then reported up the chain of command; it is unclear exactly what the individual responsibilities were or what they were known as but military life offered a much greater opportunity at this time than in the past. Historian Marc van de Mieroop writes:

Although our knowledge of the military in the Middle Kingdom is very limited, it seems that its role in society was much greater than in the Old Kingdom. The army was well organized and in the 12th dynasty it had a core of professional soldiers. They served for prolonged periods of time and were regularly stationed abroad. The army provided an outlet for ambitious men to make careers. The bulk of the troops continued to be recruited from the populations of the provinces and participated in individual campaigns only. How many troops were involved and how long they served remains unknown (112).

The military of the Middle Kingdom reached its apex under the reign of the warrior-king Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE) who was the model for the later legendary conqueror Sesostris made famous by Greek writers. Senusret III led his men on major campaigns in Nubia and Palestine, abolished the position of nomarch and took more direct control of the regions his soldiers came from, and secured Egypt's borders with manned fortifications.

THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE HYKSOS

The kings of the 12th Dynasty, like Senusret III, were strong rulers who contributed a great deal to Egyptian stability but the 13th Dynasty was weaker and failed to maintain an effective central government. The Hyksos, a Semitic people who immigrated from Syria-Palestine, settled in Lower Egypt at Avaris and, in time, had amassed enough wealth to wield political power. The rise of the Hyksos marks the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-1570 BCE) when the country was divided between the Hyksos in the north, the Egyptians in the middle, and the Nubians to the south. This situation continued, with the three engaged in trade and an uneasy peace, until the Egyptian king at Thebes, Seqenenra Taa (c. 1580 BCE), felt challenged by Apepi, the Hyksos king at Avaris, and attacked. The Hyksos were finally driven out of Egypt by Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) of Thebes and this event marks the beginning of the New Kingdom.

Egyptian Bronze Sword

The Egyptian army during the Second Intermediate Period was largely made up of Medjay, Nubian warriors who fought as mercenaries. Medjay served as scouts, light infantry, and finally as cavalry units. Prior to the arrival of the Hyksos, the horse was unknown in Egypt and so, of course, was the chariot. Although later Egyptian and Greek writers characterized the time of the Hyksos as a dark age of chaos and destruction, the foreign kings introduced a number of significant innovations to the culture, especially concerning warfare and weaponry. Egyptologist Barbara Watterson notes:

The Hyksos, being from western Asia, brought the Egyptians into contact with the peoples and the culture of that region as never before and introduced them to the horse-drawn war chariot; to a composite bow made from wood reinforced with strips of sinew and horn, a more elastic weapon with a greater range than their own simple bow; to a schimitar-shaped sword, called the Khopesh, and to a bronze dagger with a narrow blade cast in one piece with the tang. The Egyptians developed this weapon into a short sword (60).

Egypt had never been invaded and occupied by a foreign power before and the rulers of the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) wanted to make sure it never would be again. The early kings of this period, therefore, placed particular emphasis on expanding the borders of the country to create buffer zones and, in doing so, launched the Egyptian Empire.

THE ARMY OF THE EMPIRE

The period of the New Kingdom is the best known by modern day audiences with some of the most famous rulers ( Hatshepsut, Thuthmoses III, Seti I, Ramesses II ). It was the period when Egypt reached its height in prestige, power, and wealth. Van de Mieroop writes:

New Kingdom Egypt was an imperialist state: the country annexed territories outside its traditional borders and controlled them for its own benefit. This policy had its roots in earlier periods, when military conquest was a regular part of royal duties, but peaked in the New Kingdom when Egypt was in an almost permanent state of war (157).

Statue of King Thutmose III

The empire of the New Kingdom starts with Ahmose I's pursuit of the Hyksos out of Egypt, through Palestine, and into Syria but really begins with the reign of Amenhotep I (c. 1541-1520 BCE) who expanded the southern borders into Nubia.Thuthmose I (1520-1492 BCE) went further and campaigned through Palestine and Syria into Mesopotamia, reaching the Euphrates River. Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) sent expeditions to Nubia and Syria and organized a trade mission to Punt which included a military escort. Thuthmose III (1458-1425 BCE), however, is considered the greatest warrior king of the early New Kingdom, conquering Libya, expanding into Nubia, and securing regions throughout the Levant. Thuthmose III, leading at least 17 different campaigns in 20 years, established the Egyptian Empire at its height and, to do this, required a professional army. Bunson writes:

The army was no longer a confederation of nome levies but a first-class military force. The king was the commander in chief but the vizier and another administrative series of units handled the logistical and reserve affairs...The army was organized into divisions, both chariot and infantry. Each division numbered approximately 5,000 men. These divisions carried the names of the principal deities of the nation (170).

Under this new organization, the chain of command in a division, from the lowest to highest rung, was strictly hierarchical. In each division there was an officer in charge of 50 soldiers who reported to a superior officer in charge of 250 men. This officer, in turn, reported to a captain who was responsible to a troop commander. Above the troop commander was the troop overseer, a military official in charge of a garrison, who reported to the fortification overseer, a higher official in charge of the forts where the division was stationed, who reported to a lieutenant commander. The lieutenant commander reported to the general who was responsible to the vizier and the pharaoh.

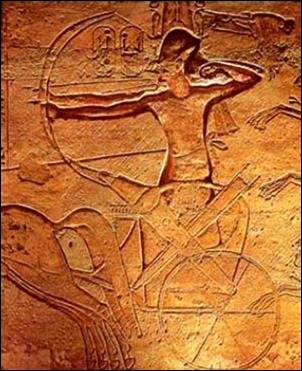

Ramesses II at The Battle of Kadesh

An important aspect of this new army was the horse-drawn chariot introduced by the Hyksos. Van de Mieroop notes how, "Charioteers were trained fighters and also men of wealth, who provided their own equipment. They received greater rewards than other soldiers and had a high social status" (158). The Egyptians modified the chariot of the Hyksos to make it lighter, more maneuverable, and faster. Each chariot held two men, a driver and a warrior. They wore scale armor on the upper body and a light kilt below. The driver was a highly trained charioteer who controlled the vehicle while the warrior, armed with bow, arrows, and a spear, engaged the enemy. Chariot forces were divided into squadrons of 12 chariots and 24 men with a thirteenth as squadron commander.

It was this army which expanded Egypt into an empire and allowed for the opulent reigns of pharaohs such as Amenhotep III(1386-1353 BCE) under whose rule Egypt enjoyed unprecedented peace and prosperity. This is not to say there were no conflicts during his reign but the army kept such unpleasantness far from the borders of the country. This is also the army, under Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE), which engaged the Hittites in 1274 BCE at the famous Battle of Kadesh.

Ramesses II moved the capital of Egypt from Thebes to a new city he built on the former site of Avaris in Lower Egypt, Per-Ramesses ("City of Ramesses"). As usual, this pharaoh spared no expense in lavishing his new capital with adornments and monuments, temples to the gods, and beautiful buildings but, as Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson explains, there was more going on at Per-Ramesses than architectural advancements and religious festivals:

While the court scribes and poets lauded Per-Ramesses as a great royal residence, filled with exuberance and joy, there was also a more menacing side to this most ambitious of royal projects. One of the largest buildings was a vast bronze-smelting factory whose hundreds of workers spent their days making armaments. State-of-the-art high-temperature furnaces were heated by blast pipes worked by bellows. As the molten metal came out, sweating laborers poured it into molds for shields and swords. In dirty, hot, and dangerous conditions, the pharaoh's people made the weapons for the pharaoh's army. Another large area of the city was given over to stables, exercise grounds, and repair works for the king's chariot corps...In short, Per-Ramesses was less pleasure dome and more military-industrial complex (314).

Ramesses II launched his campaign against the Hittites at Kadesh from Per-Ramesses, riding in his chariot at the head of four divisions of 20,000 men. According to his inscriptions, the battle was an overwhelming Egyptian victory but his opponent, Muwatalli II of the Hittite Empire, claimed precisely the same for his side. Scholars today have concluded that the Battle of Kadesh was more of a draw than a victory for either side but Ramesses had details of his great victory inscribed and read throughout the country and the conflict would result in the world's first peace treaty signed between the Egyptian and Hittite Empires in 1258 BCE.

Hittite War Chariot

THE EGYPTIAN NAVY

Besides the army and the chariotry, there was a third branch of the military, the navy. As noted, in the Old Kingdom the navy was used primarily to transport infantry. Even as late as the Second Intermediate Period, Kamose was using the navy simply as transport to bring his troops down the Nile for the sack of Avaris. In the New Kingdom, however, the navy became more prestigious as foreign invaders threatened Egypt's prosperity by sea.

The best documented, and most determined, of these invaders are known as the Sea Peoples, a mysterious group who have yet to be positively identified. They seem to have been a coalition of different ethnicities who harried the coasts of the Mediterranean between c. 1276-1178 BCE. Ramesses II, his successor Merenptah (1213-1203 BCE) and Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE) all fought off the Sea Peoples during their reigns.

Ramesses II, who had a very efficient intelligence network, learned of the coming invasion in time to place his navy along the coast at the mouth of the Nile. He then positioned a small fleet in a defensive position to draw the ships of the Sea Peoples into a trap. Once they were in position, he released his more numerous and larger ships from the sides and destroyed his opponent.

This engagement, like many others of the Egyptian navy, was fought at sea by land troops. Although the soldiers were trained to fight on water they were not seamen. The Egyptians were not a seafaring people and their navy gives evidence of this. The ships were often incredibly large with a crew of around 250 men. Smaller ships held a crew of 50 with 20 of these delegated to rowing, sailing, maneuvering the vessel and 30 assigned to combat. Although Ramesses II emphasized his victory in a sea battle, it was actually a land battle fought on water. The Egyptian ships closed with those of the Sea Peoples enabling boarding and then sinking of the enemy ships; the ships themselves did not do battle.

Egyptian Warship Model

This same is true of Ramesses III's engagement with the Sea Peoples. He incorporated his predecessor's trick of luring the Sea Peoples into a trap and then relied on guerilla warfare to destroy them. Merenptah avoided a sea engagement entirely and met the enemy on land at Pi-yer where his New Kingdom army slaughtered over 6,000 enemy soldiers.

The true value of the Egyptian navy was intimidation of potential invaders and transport of land troops quickly. Thuthmoses III used the navy to good effect in a number of campaigns and former cargo ships were frequently conscripted and turned into naval vessels for campaigns up or down the Nile. The ships would be outfitted with bulwarks to protect the crew from incoming missiles and would sometimes also be improved for maneuverability.

DECLINE OF THE EGYPTIAN MILITARY

Ramesses III was the last effective pharaoh of the New Kingdom and, after he died, great military successes became more and more a thing of the past. The pharaohs who followed him were not strong enough to hold the empire and it began to fall apart. A contributing factor to this decline was actually Ramesses II's decision to build Per-Ramesses and move his capital there from Thebes. Thebes was the site of the great Temple of Amun at Karnak and the priests of Amun, not just there but throughout Egypt, were very powerful. When the capital moved to Per-Ramesses the priests at Thebes found they had a good deal more freedom to amass even more wealth and power than before. By the time of the reign of Ramesses XI (1107-1077 BCE) the country was divided between his rule from Per-Ramesses and that of the priests of Amun at Thebes.

This division begins the era known as the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE). Whatever power Egypt had at sea was eclipsed by the Greek and Phoenician navies of the time which were much faster, better equipped, and manned by experienced seafarers. Egypt entered the so-called Iron Age II in c. 1000 BCE when they began producing iron tools and weapons. Forging iron required charcoal from burned lumber, however, and Egypt had few trees. In 671 BCE the country was invaded by the Assyrian king Esarhaddon who, with his professional army wielding weapons of iron, massacred the Egyptian army, burned the city of Memphis, and brought royal captives back to Nineveh. In 666 BCE his son Ashurbanipal invaded Egypt and conquered the land all the way past Thebes. Again, the iron weapons, better armor, and tactics of the Assyrians proved superior to the Egyptian military.

Assyrian Battle Scene

Egyptian history enters the Late Period (525-332 BCE) after the Assyrian invasions which is marked by dwindling power of Egyptian rulers and incessant warfare. The Egyptian royalty fought one another for supremacy using Greek mercenaries who would as easily fight for one side as another. Eventually many of these Greek soldiers stopped fighting entirely and just settled with families in Egypt.

The Egyptian military had acquired iron weapons by this time and developed a strong cavalry but these innovations were not enough to raise it to the level of efficiency and power it had before. Iron was very expensive because all the elements required had to be imported.

The Persians invaded in 525 BCE and defeated the Egyptian garrison at Pelusium but this had nothing to do with superior military might. The Persian general Cambyses II knew of the great veneration the Egyptians had for animals in general and cats in particular. He ordered his men to round up as many animals as possible and drive them before the army. Further, he had his soldiers paint the image of the goddess Bastet, among the most popular of all Egyptian deities, on their shields. He then marched on the city with the animals in front of him declaring that he would hurl cats over the walls if he did not receive an immediate surrender. The Egyptians, fearing for the safety of the animals (and also their own if they should offend Bastet), lay down their arms and surrendered. Afterwards, Cambyses II is said to have thrown cats from a sack into the faces of the Egyptians in contempt.

Alexander the Great took Egypt from the Persians in 331 BCE and, after his death, it came under the rule of his general Ptolemy who became Ptolemy I of Egypt (323-283 BCE). The Ptolemies were Macedonian-Greek rulers who employed the military tactics and weaponry of their own country. The history of ancient Egyptian warfare essentially ends with the New Kingdom. Whatever innovations and progress in weaponry were made after 1069 BCE no longer mattered on a large scale to the Egyptian military because there was no longer a strong central government to support it.

Ancient Egyptian Writing › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Ancient Egyptian writing is known as hieroglyphics ('sacred carvings') and developed at some point prior to the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 -2613 BCE). According to some scholars, the concept of the written word was first developed in Mesopotamia and came to Egypt through trade. While there certainly was cross-cultural exchange between the two regions, Egyptian hieroglyphics are completely Egyptian in origin; there is no evidence of early writings which describe non-Egyptian concepts, places, or objects, and early Egyptian pictographs have no correlation to early Mesopotamian signs. The designation 'hieroglyphics' is a Greek word;de Egyptenaren verwezen naar hun schrijven als medu-netjer, 'woorden van de god', zoals zij geloofden het schrijven was aan hen gegeven door de grote god Thoth.

Volgens een oude Egyptische verhaal, in het begin van de tijd Thoth aangemaakt zichzelf en, in de vorm van een ibis, lag het kosmische ei, dat de hele schepping gehouden. In een ander verhaal, Thoth voortgekomen uit de lippen van de zonnegod Ra aan het begin van de tijd, en in een ander, werd hij geboren uit de contendings van de goden Horus en Set, die de krachten van de orde en chaos. In al deze, maar de constante is dat Thoth werd geboren met een enorme breedte van kennis en, een van de belangrijkste, de kennis van de kracht van woorden.

Thoth gaf de mens deze kennis vrij, maar het was een verantwoordelijkheid hij hen verwacht dat zij serieus te nemen. Woorden zou kunnen kwetsen, genezen, verheffen, te vernietigen, te veroordelen, en zelfs iemand van de dood naar het leven te verhogen. Egyptoloog Rosalie David zegt hierover:

Het belangrijkste doel van het schrijven was niet decoratief, en het was niet oorspronkelijk bedoeld voor literaire of commercieel gebruik. Zijn belangrijkste taak was om een middel waarmee bepaalde begrippen of gebeurtenissen tot stand gebracht kon worden voorzien. De Egyptenaren geloofden dat als er iets werd comitted aan het schrijven van het kon worden herhaaldelijk "gemaakt te gebeuren" door middel van magie. (199)

Thoth

Dit concept is niet zo vreemd als het eerste gezicht zou lijken. Elke schrijver weet dat men vaak geen idee wat men wil zeggen tot het einde van het eerste ontwerp, en elke fervent lezer begrijpt de "magie" van het ontdekken van onbekende werelden tussen de covers van een boek en het maken van die magie weer gebeuren elke keer dat de boek wordt geopend. David's verwijzing naar "concepten of events" tot stand komen door middel van het schrijven is een gemeenschappelijk begrip tussen schrijvers. Amerikaanse schrijver William Faulkner verklaarde in zijn Nobelprijs-mailadres dat hij schreef "uit de materialen van de menselijke geest iets te creëren die niet bestond vóór" (1). Deze zelfde motivatie is met andere woorden uitgedrukt door vele schrijvers door de eeuwen heen, maar voordat een van hen zelfs bestond de oude Egyptenaren begrepen dit concept ook.De grote gift van Thoth was de mogelijkheid niet alleen te zijn zelf uit te drukken, maar om letterlijk in staat zijn om de wereld te veranderen door de kracht van woorden. Voordat dat kan gebeuren, echter, voordat de gave om zijn volle gebruik kan worden gebracht, het moest worden begrepen.

DE OPRICHTING VAN SCHRIJVEN

Hoezeer Thoth had te maken met het geven van de mensen hun systeem van schrijven (en, voor de Egyptenaren, 'de mensheid' gelijk 'Egyptische'), de oude Egyptenaren hadden uit te werken voor zichzelf wat dit cadeau was en hoe het te gebruiken. Ergens in het laatste deel van de Predynastic periode in Egypte (c 6000 -.. C 3150 BCE) begonnen zij symbolen eenvoudige concepten. Egyptoloog Miriam Lichtheim schrijft hoe deze vroege script"Beperkt tot de kortste notaties ontworpen om een persoon of een plaats, een gebeurtenis of een bal identificatie" (3). Waarschijnlijk is de vroegste doel het schrijven van gediend was in de handel, om informatie over producten, prijzen, aankopen over te brengen, tussen een punt en een ander. De eerste echte bestaande bewijs van de Egyptische schrijven, komt echter uit graven in de vorm van het aanbieden van lijsten in de vroeg-dynastieke periode.

Egyptische Hiërogliefen

Death was not the end of life for the ancient Egyptians; it was only a transition from one state to another. The dead lived on in the afterlife and relied upon the living to remember them and present them with offerings of food and drink. An Offering List was an inventory of the gifts due to a particular person and inscribed on the wall of their tomb. Someone who had performed great deeds, held a high position of authority, or led troops to victory in battle were due greater offerings than another who had done relatively little with their lives. Along with the list was a brief epitaph stating who the person was, what they had done, and why they were due such offerings. These lists and epitaphs might sometimes be quite brief but most of the time were not and became longer as this practice continued. Lichtheim explains:

The Offering List grew to enormous length till the day on which an inventive mind realized that a short Prayer for Offerings would be an effective substitute for the unwieldy list. Once the prayer, which may already have existed in spoken form, was put into writing, it became the basic element around which tomb-texts and representations were organized. Similarly, the ever lengthening lists of an official's ranks and titles were infused with life when the imagination began to flesh them out with narration, and the Autobiography was born. (3)

The autobiography and the prayer became the first forms of literature in Egypt and were created using the hieroglyphic script.

DEVELOPMENT & USE OF HIEROGLYPHIC SCRIPT

Hiërogliefen ontwikkeld uit het begin van de pictogrammen. Mensen gebruikte symbolen, afbeeldingen om concepten te vertegenwoordigen, zoals een persoon of gebeurtenis. Het probleem met een pictogram, is echter dat de informatie die het bevat is vrij beperkt. Men kan een beeld van een vrouw en een gelijkspel tempel en een schaap, maar heeft geen manier om het doorgeven van hun verbinding. Is de vrouw die vanuit of naar de tempel gaan? Is de schapen een offer dat ze leidt tot de priesters of een geschenk aan haar van hen? Is de vrouw zelfs naar de tempel op alle of is ze alleen maar loopt een schaap in de buurt? Zijn de vrouw en schapen zelfs met betrekking op alle? De vroege pictographic schrijven ontbrak elke mogelijkheid om deze vragen te beantwoorden.

De Egyptenaren ontwikkelde het hetzelfde systeem als SUMERIANS maar voegde logogrammen (symbolen die woorden) EN Ideogrammen HUN SCRIPT.

De Sumeriërs van het oude Mesopotamië was al komen over dit probleem schriftelijk en creëerde een geavanceerde script c. 3200 BCE in de stad van Uruk. De theorie dat de Egyptische script ontwikkeld van Mesopotamische schrijven sterkst wordt uitgedaagd door deze ontwikkeling, in feite, want als de Egyptenaren de kunst van het schrijven van de Sumeriërs had geleerd, zouden ze het stadium van pictogrammen omzeild en begonnen met de Sumerische creatie van fonogrammen - symbolen geluid representeren. De Sumeriërs geleerd om hun geschreven taal door middel van symbolen rechtstreeks vertegenwoordigt die taal, zodat als ze wilden een aantal specifieke informatie doorgeven over een vrouw, een tempel en een schaap, konden ze schrijven uit te breiden, "De vrouw nam de schapen als een offer aan de tempel," en de boodschap was duidelijk.

De Egyptenaren ontwikkelde dit zelfde systeem maar voegde logogrammen (symbolen die woorden) en ideogram hun script. Een ideogram een "sense teken dat een bepaalde boodschap duidelijk overbrengt via een herkenbaar symbool. Het beste voorbeeld van een ideogram is waarschijnlijk een minteken: men erkent dat het betekent aftrekken. De emoji is een modern voorbeeld vertrouwd aan iedereen kennis te maken met sms; het plaatsen van het beeld van een lachend gezicht aan het einde van zijn zin laat een lezer weten dat men een grapje of vindt het onderwerp grappig. De fonogrammen, logogram en ideogram vormden de basis voor het hiërogliefen script. Rosalie David legt uit:

Er zijn drie soorten van fonogrammen in hieroglypics: uniliteral of alfabetische tekens, waar men hiëroglief (foto) staat voor een enkele medeklinker of sound waarde; biliteral tekens, waar men heiroglyphs vertegenwoordigt twee medeklinkers; en triliteral tekenen waar men hiëroglief vertegenwoordigt drie medeklinkers. Er zijn vierentwintig herioglyphic borden in de Egyptische alfabeten dit zijn de fonogrammen meest gebruikte. Maar aangezien er was nooit een puur alfabetisch systeem, werden deze borden langs andere fonogrammen (biliterals en triliterals) en ideogrammen geplaatst. Ideogrammen werden vaak geplaatst aan het eind van een woord (gespeld in fonogrammen) om de betekenis van dat woord te verduidelijken en, wanneer op deze manier gebruikt, verwijzen we naar hen als "determinatives." Dit helpt op twee manieren: de toevoeging van een bepalend helpt om de betekenis van een bepaald woord te verduidelijken, omdat sommige woorden er hetzelfde uitzien of identiek zijn aan elkaar wanneer gespeld en neer alleen in de fonogrammen geschreven; en beacuse determinatives staan aan het einde van het woord dat ze kunnen aangeven waar een woord eindigt en de andere begint. (193)

Egyptische Stela van Horemheb

A modern-day example of how hieroglyphics were written would be a text message in which an emoji of an angry face is placed after an image of a school. Without having to use any words one could convey the concept of "I hate school" or "I am angry about school." If one wanted to make one's problem clearer, one could place an image of a teacher or fellow student before the angry-face-ideogram or a series of pictures telling a story of a problem one had with a teacher. Determinatives were important in the script, especially because hieroglyphics could be written left-to-right or right-to-left or down-to-up or up-to-down. Inscriptions over temple doors, palace gates, and tombs go in whatever direction was best served for that message.The beauty of the final work was the only consideration in which direction the script was to be read. Egyptologist Karl-Theodor Zauzich notes:

The placement of hieroglyphs in relation to one another was governed by aesthetic rules. The Egyptians always tried to group signs in balanced rectangles. For example, the word for "health" was written with the three consonants snb. These would not be written [in a linear fashion] by an Egyptian because the group would look ugly, it would be considered "incorrect". The "correct" writing would be the grouping of the signs into a rectangle...The labor of construction was lightened somewhat by the fact that individual hieroglyphs could be enlarged or shrunk as the grouping required and that some signs could be placed either horizontally or vertically.Scribes would even reverse the order of signs if it seemed that a more balanced rectangle could be obtained by writing them in the wrong order. (4)

The script could easily be read by recognizing the direction the phonograms were facing. Images in any inscription always face the beginning of the line of text; if the text is to be read left-to-right then the faces of the people, birds, and animals will be looking to the left. These sentences were easy enough to read for those who knew the Egyptian language but not for others.Zauzich notes how "nowhere among all the hieroglyphs is there a single sign that represents the sound of a vowel" (6). Vowels were placed in a sentence by the reader who understood the spoken language. Zauzich writes:

This is less complicated than it sounds. For example, any of us can read an that consists almost entirely of consonants:

3rd flr apt in hse, 4 lg rms, exclnt loc nr cntr, prkg, wb-frpl, hdwd flrs, skylts, ldry, $600 incl ht (6).

In this same way, the ancient Egyptians would be able to read hieroglyphic script by recognizing what 'letters' were missing in a sentence and applying them.

OTHER SCRIPTS

Hieroglyphics were comprised of an 'alphabet' of 24 basic consonants which would convey meaning but over 800 different symbols to express that meaning precisely which all had to be memorized and used correctly. Zauzich answers the question which may immediately come to mind:

It may well be asked why the Egyptians developed a complicated writing system that used several hundred signs when they could have used their alphabet of some thirty signs and made their language much easier to read and write. This puzzling fact probably has a historical explanation: the one-consonant signs were not "discovered" until after the other signs were in use. Since by that time the entire writing system was established, it could not be discarded, for specific religious reasons. Hieroglyphics were regarded as a precious gift of Thoth, the god of wisdom. To stop using many of these signs and to change the entire system of writing would have been considered both a sacrilege and an immense loss, not to mention the fact that such a change would make all the older texts meaningless at a single blow. (11)

Even so, hieroglyphics were obviously quite labor-intensive for a scribe and so another faster script was developed shortly after known as hieratic ('sacred writing'). Hieratic script used characters which were simplified versions of hieroglyphic symbols. Hieratic appeared in the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt after hieroglyphic writing was already firmly developed.

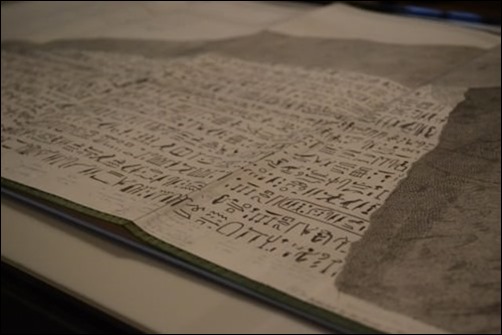

Hieratic Book of the Dead of Padimin

Hieroglyphics continued to be used throughout Egypt's history in all forms of writing but came primarily to be the script of monuments and temples. Hieroglyphics, grouped in their beautifully formed rectangles, leant themselves to the grandeur of monumental inscriptions. Hieratic came to be used first in religious texts but then in other areas such as business administration, magical texts, personal and business letters, and legal documents such as wills and court records. Hieratic was written on papyrus or ostraca and practiced on stone and wood. It developed into a cursive script around 800 BCE (known as 'abnormal hieratic') and then was replaced c. 700 BCE by demotic script.

Demotic script ('popular writing') was used in every kind of writing while hieroglyphics continued to be the script of monumental inscriptions in stone. The Egyptians called demotic sekh-shat, 'writing for documents,' and it became the most popular for the next 1,000 years in all kinds of written works. Demotic script seems to have originated in the Delta region of Lower Egypt and spread south during the 26th Dynasty of the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE). Demotic continued in use through the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE) and the Ptolemaic Dynasty (332-30 BCE) into Roman Egypt when it was replaced by Coptic script.

Rosetta Stone Detail, Demotic Text

Coptic was the script of the Copts, Egyptian Christians, who spoke Egyptian dialects but wrote in the Greek alphabet with some additions from demotic script. Since the Greek language had vowels, the Copts incorporated them in their script to make the meaning clear to anyone reading it, no matter what their native language. Coptic script was used to copy and preserve a number of important documents, most notably the books of the Christian New Testament, and also served to provide the key to later generations for understanding hieroglyphics.

LOSS & DISCOVERY

It has been argued that the meaning of hieroglyphics was lost throughout the later periods of Egyptian history as people forgot how to read and write the symbols. Actually, hieroglyphics were still in use as late as the Ptolemaic Dynasty and only fell out of favor with the rise of the new religion of Christianity during the early Roman Period. There were lapses throughout the country's history in the use of hieroglyphics, but the art was not lost until the world the script represented changed. As Coptic script continued to be used in the new paradigm of Egyptian culture ; hieroglyphic writing faded into memory. By the time of the Arab Invasion of the 7th century CE, no one living in Egypt knew what the hieroglyphic inscriptions meant.

When the European nations began exploring the country in the 17th century CE, they had no more of an idea that the hieroglyphics were a written language than the Muslims had. In the 17th century CE, hieroglyphics were firmly claimed to be magical symbols and this understanding was primarily encouraged through the work of the German scholar and polymath Athanasius Kircher (1620-1680 CE). Kircher followed the lead of ancient Greek writers who had also failed to understand the meaning of hieroglyphics and believed they were symbols. Taking their interpretation as fact instead of conjecture, Kircher insisted on an interpretation where each symbol represented a concept, much in the way the modern peace sign would be understood. His attempts to decipher Egyptian writing failed, therefore, because he was operating from a wrong model.

Rosetta Stone

Many other scholars would attempt to decipher the meaning of the ancient Egyptian symbols without success between Kircher's work and the 19th century CE but had no basis for understanding what they were working with. Even when it seemed as though the symbols suggested a certain pattern such as one would find in a writing system, there was no way to recognize what those patterns translated to. In 1798 CE, however, when Napoleon's army invaded Egypt, the Rosetta Stone was discovered by one of his lieutenants, who recognized its potential importance and had it sent to Napoleon's institute for study in Cairo. The Rosetta Stone is a proclamation in Greek, hieroglyphics, and demotic from the reign of Ptolemy V (204-181 BCE). All three texts relay the same information in keeping with the Ptolemaic ideal of a multi-cultural society; whether one read Greek, hieroglyphic, or demotic, one would be able to understand the message on the stone.

Work on deciphering hieroglyphics with the help of the stone was delayed until the English defeated the French in the Napoleonic Wars and the stone was brought from Cairo to England. Once there, scholars set about trying to understand the ancient writing system but were still working from the earlier understanding Kircher had so convincingly advanced. The English polymath and scholar Thomas Young (1773-1829 CE) came to believe that the symbols represented words and that hieroglyphics were closely related to demotic and later Coptic scripts. His work was built upon by his sometimes-colleague-sometimes-rival, the philologist and scholar Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832 CE).

Champollion's notes from the Rosetta Stone

Champollion's name is forever linked with the Rosetta Stone and the decipherment of hieroglyphics because of the famous publication of his work in 1824 CE which conclusively showed that Egyptian hieroglyphics were a writing system composed of phonograms, logograms, and ideograms. Contention between Young and Champollion over who made the more significant discoveries and who deserves the greater credit is reflected in the same ongoing debate in the present day by scholars. It seems quite clear, however, that Young's work lay the foundation on which Champollion was able to build but it was Champollion's breakthrough which finally deciphered the ancient writing system and opened up Egyptian culture and history for the world.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License