Antigonus I › Antioch › Buddhism in Ancient Japan » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Antigonus I › Who was

- Antioch › Origins

- Buddhism in Ancient Japan › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Antigonus I › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Donald L. Wasson

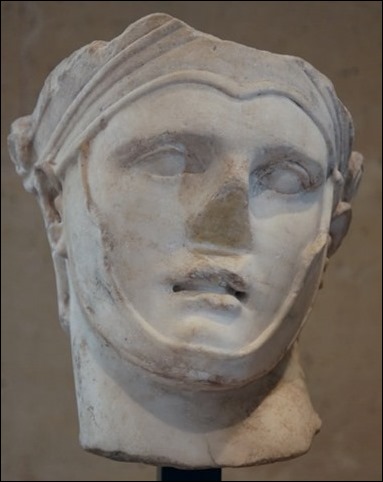

Antigonus I Monophthalmus ("the One-Eyed") (382 -301 BCE) was one of the successor kings to Alexander the Great, controlling Macedonia and Greece.

When Alexander the Great died in 323 BCE, a debate ensued over his massive kingdom stretching from Greece to India. It was eventually divided among three of his most loyal generals and their families -- Ptolemy I and his descendants (among them Queen Cleopatra ) would rule Egypt ; Seleucos and his family ruled Syria and the Near Eastern provinces, and lastly, the descendants of Antigonus ruled Macedonia and Greece. Although this was the way it ended, it was not how it began. The in-fighting that followed Alexander's death and the battle over his kingdom lasted over thirty years, and one of those who wished to be the successor to the great Alexander was Antigonus the one-eyed.

Antigonus was a Macedonian general and nobleman who served ably under both Alexander the Great and his father Phillip II.After Phillip's death by assassination at the hands of his former bodyguard Pausanias, Alexander decided to follow his father's dream and cross the Hellespont into Anatolia to meet and defeat Darius III and conquer the Persian Empire.Antigonus, at the age of sixty, followed Alexander on this campaign.

ANTIGONUS WAS A MACEDONIAN GENERAL AND NOBLEMAN WHO SERVED ABLY UNDER BOTH ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND HIS FATHER PHILLIP II.

After crossing the Hellespont, Alexander marched his troops northward, pausing briefly to give homage to the Homeric heroes, Achilles and the fallen Greeks at Troy. He then moved southward defeating the Persians at the Battle of Granicus in May 334 BCE. Before leaving to eventually meet and defeat Darius III at Issus (November 333 BCE), Alexander left Antigonus as satrap of Phrygia (western Anatolia) with a force of 1500 troops to help defend the satrapy, maintaining a capital at Celanae.He would remain there for the remainder of Alexander's war against the Persians. Antigonus' primary responsibility was to maintain Alexander's lines of supply and communication; however, his stay there did not go smoothly. After Alexander and his massive army moved further south into Syria, the Persians attempted to regain some of the territory they had lost. Antigonus and his army had to defend his domain in Phrygia on three different occasions, winning all three battles. One of these battles was against the Greek mercenary Memnon (loyal to Darius) who had recently been defeated at Granicus.

In 323 BCE Alexander died in Babylon, but just prior to dying, Alexander handed his signet ring to his senior cavalry officer Perdiccas, a possible indication to some that Alexander was naming him as a successor. Periccas immediately brought the other generals together to discuss the future of the empire. Meleager, an infantry leader, was considered (at least in his own mind) to be second in command -- a position he would not remain in for long. Perdiccas had him executed: an indication that a fight over regency of the empire lay ahead. The major question remained: Who was to rule? Perdiccas elected to wait until Roxanne and Alexander's child was born, the son who would become Alexander IV. However, the young Alexander would never rule, as both Roxanne and young Alexander were executed by Antipater ’s son Cassander in 310 BCE, solving the entire inheritance problem.

Alexander the Great

The generals finally agreed to divide Alexander's empire in the Partition of Babylon. The partition granted Antigonus the satrapy of Phrygia as well as Pamphylia and Lycia (northwestern Anatolia). Antipater remained as regent of Macedonia while his son, Cassander, received Caria (southwestern Anatolia). Ptolemy remained as regent in Egypt. Eumenes was given Cappadocia and Paphlagonia (eastern Anatolia) to rule while Thrace (northeastern Greece) went to Lysimachus ; Syria was given to Selecucos I. This division, however, was not to remain. There would be twenty more years of war. Alliances came and went, peace was inconsistent and jealousy remained throughout.

The arguments over territory began when Perdiccas became angry at Antigonus because he refused to help Eumenes keep control of his allotted territory. Antigonus wanted to avoid conflict with Periccas so he and his thirteen year old son Demetrius sought refuge in Macedonia, gaining favor of Antipater -- they united against Perdiccus and Eumenes. Eumenes was defeated and imprisoned in 321 BCE. Next, Antigonus allied himself with Antipater, Ptolemy, and Lysimachus against Perdiccas.Perdiccas died by assassination in 321 BCE thus ending the alliance.

Upon the death of his father Antipater in 319 BCE, Cassander was denied the regency of Macedonia; Antipater had believed him too young to oppose the other regents. Instead, he named Polyperchon as the new regent, who allied himself with Eumenes to maintain his regency (even though Eumenes was still imprisoned at the fortress at Nora). The other regents refused to recognize Polyperchon's authority, fearing a threat to their own regency. Eumenes escaped from his imprisonment, however, to aid Polypheron. Antigonus fought Eumenes twice, defeating him both times, with the result that Eumenes' famed Silver Shields, an elite Macedonian regiment, turned him over to Antigonus who summarily had him executed.

In order to gain the regency he felt he deserved, Cassander turned to Antigonus and Lysimachus for help. Antigonus wanted control of Macedonia, so he agreed to the alliance. Cassander gained control of Macedonia forcing Polypheron out. With Eumenes defeated, Antigonus controlled much of the eastern Mediterranean. He and his forces marched into Babylon causing Seleucos to flee to Egypt and form an alliance with Ptolemy. After Antigonus besieged the island city of Tyre, he moved his forces into Syria; however, his advances were stopped by Ptolemy and Seleucos.

Map of the Successor Kingdoms, c. 303 BCE

This desire to reunite Alexander's kingdom under his leadership brought Antigonus against the combined forces of Ptolemy, Lysimachus, Cassander, and Seleucos. After Antigonos ’s son Demetrius was defeated by Ptolemy at the Battle of Gaza, Seleucos took back Babylon. With this defeat, a limited peace was declared, lasting from 315 to 311 BCE. The peace agreement left Antigonus in control of all of Asia Minor and Syria. The uneasy peace ended when Antigonus decided to make another move at claiming Macedonia and Greece by extending a peace offering to the Greek city-states granting them self-government and withdrawal of all Macedonian troops.

The historian Diodorus spoke of this extension of a helping hand when he stated in his World History :

All the Greeks should be free, exempt from garrisons, and autonomous. The soldiers carried the motion and Antigonus dispatched messengers in every direction to announce the resolution. He calculated as follows: The Greeks' hopes for freedom would make them willing allies in the war, while the generals and satraps in the eastern satrapies, who suspected Antigonus of seeking to overthrow the kings who had succeeded Alexander, would change their minds and willingly submit to his orders when they saw him clearly taking up the war on their behalf.

While he gained support of the Greek city states, Antigonus incurred the wrath of the others who allied against him: Lysimachus invaded Asia Minor from Thrace, securing the old Greek Ionian cities and Seleucos marched through Mesopotamia and Cappadocia. The wars returned and continued for a number of years.

Seleucus I Nicator

Ptolemy, Seleucos, Cassander, and Lysimachus finally combined their forces and met Antigonus in Phrygia in 301 BCE. At the age of 80, Antigonus died in the Battle of Ipsus from the simple throw of a javelin. Demetrius fled back to Macedonia to hopefully secure his rule there. For almost two more decades, he and his son Antigonus Gonata fought for control of Macedonia, eventually gaining control, establishing the Antigonid dynasty.

How can one assess Antigonus? Was he a great general? Plutarch in his Life of Demetrios said:

If Antigonus could only have borne to make some trifling concessions, and if he had shown any moderation in his passion for empire, he might have maintained for himself till his death and left to his son behind him the first place among the kings. But he was of a violent and haughty spirit; and the insulting words as well as actions in which he allowed himself could not be borne by young and powerful princes, and provoked them into combining against him.

Plutarch later stated that as the armies of his enemies came toward him at the Battle of Ipsus, he was confident that Demetrius would still rescue him (Demetrius was engaged elsewhere in the battle). Antigonus remained that way “until he was borne down by a whole multitude of darts, and fell."

Antioch › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Donald L. Wasson

Antioch or Antiochia was an ancient city located on the Orontes River near the Amanus Mountains in Syria. The “land of four cities ”

--- Seleucia, Apamea, Laodicea, and Antiochia --- was founded by Seleucos I Nikator (Victor) between 301 and 299 BC. Some credit the city's initial founding as Antigoneia to Antigonus the One-Eyed who lost the area to Seleucos after the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE. According to some ancient sources, Seleucos was considered one of the more capable successors to the empire established by Alexander the Great. Seleucos was not one of the people in Alexander ’s inner circle, serving as one of the commanders of the hypaspists, an elect guard that served as a buffer between Alexander's cavalry and infantry. Although little mention is made of him and his relationship to Alexander, he and his descendants would rule an empire which included Antiochia for almost two hundred and fifty years.

--- Seleucia, Apamea, Laodicea, and Antiochia --- was founded by Seleucos I Nikator (Victor) between 301 and 299 BC. Some credit the city's initial founding as Antigoneia to Antigonus the One-Eyed who lost the area to Seleucos after the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE. According to some ancient sources, Seleucos was considered one of the more capable successors to the empire established by Alexander the Great. Seleucos was not one of the people in Alexander ’s inner circle, serving as one of the commanders of the hypaspists, an elect guard that served as a buffer between Alexander's cavalry and infantry. Although little mention is made of him and his relationship to Alexander, he and his descendants would rule an empire which included Antiochia for almost two hundred and fifty years.

SUCCESSOR WARS

After Alexander's death in 323 BC his empire and its future lay in ruin. Because Alexander had not named a successor, one of his generals, Perdiccos, wanted to delay any decision concerning the naming of a new leader until after the birth of Alexander and Roxanne ’s child. Another general, Ptolemy, on the other hand, wanted the empire divided immediately (he had his eye on Egypt ) --- the Wars of Successors began and would continue for almost three decades. After Ptolemy stole Alexander's body on its way to Macedonia and took it to Alexandria, Perdiccos and his army attacked Ptolemy and his forces in Egypt----- Seleucos, although initially loyal to Perdiccos, turned and sided with Ptolemy. After the defeat and death of Perdiccos, Seleucos was rewarded for his loyalty with the territory surrounding Babylon, an area east of Syria

Seleucos was unable to maintain control of his newly-acquired territory and when it was invaded by his nemesis Antigonosthe One-Eyed, he sought help from Ptolemy. In 312 BC Seleucos finally defeated Antigonos at the Battle of Gaza and regained his realm. After the Battle of Ipsus, he proved himself a very capable commander by expanding his empire into Syria, Asia Minor and India. His son, Antiochos I (281 – 261 BCE) faced a series of revolts after his father's assassination in 281 BCE and was forced to concede territory in order to maintain peace. Unfortunately, his son, Antiochos II, (261 – 247 BCE) inherited a war against the Ptolemys of Egypt, the Second Syrian War, from his father.

THE CITY WOULD MAINTAIN ITS STATUS AS A CAPITAL WELL INTO THE TIME OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE.

In an attempt to make peace, Antiochos II agreed to divorce and exile his wife Laodice and their sons to marry Ptolemy II's daughter, Berenice Syra. When he died, his wife (Berenice) and ex-wife (Laodice) fought over whose son should be named heir. Berenice, who had the support of the people of Antiochia, asked her brother and new ruler of Egypt, Ptolemy III, to help secure her infant son's right to sit on the throne. When Ptolemy arrived in Antiochia, he found his sister and nephew had been assassinated. A war, the third Syrian War or Laodicean War, erupted. Peace brought control of the port of Antioch, Seleucia, to Ptolemy, but Seleucos II (Antiochos and Laodice's son) inherited the throne and was able to retain Antiochia, making it his empire's new capital.

Mosaic of the Judgement of Paris

ROMAN ANTIOCH

The city would maintain its status as a capital well into the time of the Roman Empire. Because of its location on several major trade routes (primarily the spice trade), the city and its international population served as a strategic, economic and intellectual center for both the Seleucid as well as Roman Empires. The city's importance to the Roman Empire sometimes rivaled that of Egypt's chief city Alexandria.

Due to the reign of several feeble rulers, in 64 BCE Pompey made the region a Roman province. As with other Roman cities, the city would benefit from Roman rule. Antiochia would become Romanized containing aqueducts, public baths, and even an amphitheater. Its sumptuous palaces (built by the Selecuid monarchs) became vacation residences of many Roman emperors.Septimus Severus took away the city's independence when they supported Pescennius Niger of Syria instead of him for Roman emperor. Because it was located on a major fault, the city was damaged by both a great fire and several earthquakes (Earthquakes occurred under Tiberius, Caligula, Hadrian and Diocletian ).

Aureus from Antioch

Antiochia was rebuilt by the Roman emperor Trajan, serving as his army's winter quarters. After the Empire was divided during the reign of Diocletian, the city fell into the Byzantine or eastern half. Under the rule of Constantine when the empire was reunited, it would be a leading city in the rise of Christianity, even containing a school for Biblical studies. When the last pagan emperor, Julian the Apostate (361 – 363 CE) passed through Syria on his way to fight the Persians, he stopped at Antioch in 362 CE. The city was forced to house and feed his army. The resulting crisis over the price of grain eventually led to both a famine and food riots. Later, it would be sacked by the Huns in the 5 th century and eventually captured by the Arabs in the 7 th century.

Buddhism in Ancient Japan › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

Buddhism was introduced to ancient Japan via Korea in the 6th century CE with various sects following in subsequent centuries via China. It was readily accepted by both the elite and ordinary populace because it confirmed the political and economic status quo, offered a welcoming reassurance to the mystery of the afterlife, and complemented existing Shintobeliefs. Buddhist monasteries were established across the country, and they became powerful political players in their own right. Buddhism was also a key driver in fostering literacy, education in general, and the arts in ancient Japan.

Kokuzo Bosatsu, Todaiji

INTRODUCTION TO JAPAN

Buddhism was introduced into Japan in either 538 CE or 552 CE (traditional date) from the Korean kingdom of Baekje ( Paekche ). It was adopted by the Soga clan particularly, which had Korean roots and was practised by the significant Korean immigrant population in Japan at that time. Buddhism received official government support in 587 CE during the reign of Emperor Yomei (585-587 CE), even if some aristocratic clan groups (the Monobe and Nakatomi especially) opposed it and still adhered to purely Shinto beliefs. Buddhism reinforced the idea of a layered society with different levels of social status with the emperor very much at the top and protected by the Four Guardian Kings of Buddhist law. The aristocracy could also handily claim that they enjoyed their privileged position in society because they had accumulated merit in a previous life.

ONCE OFFICIALLY ADOPTED, MONKS, SCHOLARS & STUDENTS WERE REGULARLY SENT TO CHINA TO LEARN THE TENETS OF BUDDHISM IN MORE DEPTH.

In addition to the reinforcement, Buddhism gave to the status quo; the adoption of Buddhism, it was hoped, would be looked on favourably by the more advanced neighbouring cultures of Korea and China and enhance Japan's reputation as a rising civilised nation in East Asia. Once officially adopted, monks, scholars, and students were regularly sent to China to learn the tenets of Buddhism in more depth and bring back that knowledge, along with art and even sometimes relics, for the benefit of the Japanese people.

PRINCE SHOTOKU & THE SPREAD OF BUDDHISM

The man credited with really putting Buddhism at the forefront of Japanese religious practices is Prince Shotoku (574-622 CE), who ruled Japan as regent from 594 CE until his death. Shotoku famously drew up a new constitution (or, perhaps more accurately, an ethical code) in 604 CE called the Seventeen Article Constitution ( Jushichijo-kenpo ). The points made therein attempted to justify the centralisation of government and emphasised both Buddhist and Confucian principles, especially the importance of harmony ( wa ). Shotoku particularly emphasised the reverence of Buddhism, as seen in Article II of his constitution:

Sincerely reverence the three treasures. The three treasures, Buddha, the Law and the Priesthood, are the final refuge of the four generated beings, and are the supreme objects of faith in all countries. What man in what age can fail to reverence this law? Few men are utterly bad. They may be taught to follow it. But if they do not betake them to the three treasures, how shall their crookedness be made straight? (Henshall, 499)

True to his own declaration, Shotoku built many temples and monasteries, formed a body of artists to create Buddhist images, and he was himself a student of its teachings, writing commentaries on three sutras. During his reign, Shotoku built 46 Buddhist monasteries and temples, the most important of which were the Shitennoji, Hokoji (596 CE), and Horyuji.

Prince Shotoku

IMPERIAL FAVOUR

The spread continued with the full support of Emperor Temmu (r. 672-686 CE) and Empress Jito (r. 686-697 CE) who built yet more temples, had more copies of sutras made, and who used monasteries as depots for official population and tax records.Emperor Shomu (r. 724-749 CE) was even more ambitious and set out to build a temple in every province, each with its own seven-storied pagoda, a plan that raised taxation to brutal levels. Major temples were built at the then capital Nara, too, such as Todaiji, finally completed in 752 CE in a project supervised by the celebrated monk Gyogi (668-749 CE). Emperor Shomu was also important as he began the strategy of an emperor abdicating in favour of his chosen successor and then joining a monastery but still pulling political strings behind the latticed screens in what became known as 'cloistered government'.

At the same time as endorsing Buddhism, the Japanese elite was also wary of its powers and particularly concerned that a charismatic individual might abuse the reverence of the populace and form a following which could threaten the political stability of the state. For this reason, a body of laws was passed in the 8th century CE (the Taiho ritsuryo in 702 CE and Yoro ritsuryo in 757 CE) which forbade monks to have private chapels, practise divination, make any attempt to actively convert believers of one faith to another, and use magic to cure illness. Neither could monks or nuns accept gifts of slaves, cattle, or weapons, own land, buildings or valuables in their own name, trade, collect interest on loans, or even become a monk after the required period of study without official permission.

BUDDHIST MONKS COULD NOT MAKE ANY ATTEMPT TO ACTIVELY CONVERT BELIEVERS OF ONE FAITH TO ANOTHER OR USE MAGIC TO CURE ILLNESS.

In another precaution, Buddhist monasteries and monks were carefully monitored and their actions subject to the laws which applied to all citizens, even if their punishments were usually a little more lenient. These measures did not actually achieve their aim as there are many instances of monks and temples abusing their position, illegally acquiring land, committing fraud, practising exorbitant usury (which often rendered the peasantry unable to pay their taxes), and making a healthy living as pawnbrokers charging 180% per annum.

CO-EXISTENCE WITH SHINTO

The indigenous beliefs of the ancient Japanese included animism and Shinto and neither were particularly challenged by the arrival of Buddhism. Shinto, especially, with its emphasis on the here and now and this life, left a significant gap regarding what happens after death and here Buddhism was able to complete the religious picture for most people. As a consequence, both religions co-existed, many people practised both, and even temples of both faiths existed together on the same site. Many Buddhist deities and figures from Indian mythology were readily incorporated into the already vast Shinto pantheon. At the same time Shinto gods acquired Buddhist names (Ryobu Shinto) so that, for example, the sun goddess Amaterasu was considered an avatar of Dainichi; and Hachiman, the god of war and culture, was the avatar of the Amida Buddha.

Buddha, Todaiji Temple

Even artworks of one religion appeared in the buildings of the other and priests frequently administered the temples or shrines of their counterpart religion. An imperial edict in 764 CE did officially place Buddhism above Shinto, but for the majority of the ordinary population, the opposite was probably true. One area where Buddhism almost completely replaced older beliefs was in death rituals as the Buddhist practice of cremation was widely adopted by all levels of society.

BUDDHISM & WIDER SOCIETY

Buddhist monasteries were frequently given free land and an exemption from tax by emperors eager to have a blessing on their reign, and this resulted in them becoming both economically powerful and politically influential. Monasteries were able to pay for their own armed attendants, a necessary precaution in turbulent times when warlords and bandits frequently caused havoc far from the imperial capital and, more importantly, a useful source of muscle to bend local officials to their way of thinking. The monasteries became so powerful that Emperor Kammu (r. 781-806 CE) had even moved the capital from Nara in 784 CE to get away from the Buddhist temples around the city. This did not stop the monasteries, especially Kofukuji, Todaiji, Enryakuji, and Onjoji from using force many times throughout the 10th and 11th centuries CE to expand their domains and gain favourable conditions from local governors and administrators. Rivalries, inevitably, grew up between monasteries, notably between To-ji and Kyosan.

On a more peaceful note, monasteries were an important part of the local community, providing schools and facilities for higher studies, libraries, and food and shelter to the needy. Monks also helped in communal projects such as road, bridge, and irrigation building - even if this sometimes irked the imperial court when the monks received large donations from a grateful public and caused some emperors to ban monks from leaving their monasteries.

To-ji Pagoda, Kyoto

IMPORTANT BUDDHIST FIGURES

Buddhism continued to evolve as a faith in both India and China with new sects developing, which eventually made their way to Japan via monks who studied abroad. The first six important sects in Japan were the Kusha, Sanron, Ritsu, Jojitsu, Kegon, and Hosso. Two of the most noted scholar monks were Kukai (774-835 CE) and Saicho (767-822 CE), who founded two more sects, the Shingon and Tendai respectively, both of which belong to the Mahayana (Great Vehicle) branch of Buddhism.

Kukai & Shingon Buddhism

Kukai studied in China between 804 and 806 CE and became an advocate of esoteric Buddhism or mikkyo which meant that only the initiated, only those who gave up their worldly life and resided in a monastery could know the Buddha and so achieve enlightenment. The Shingon (or 'True Word') Sect which Kukai studied in China (there known as Quen-yen) held that Buddhist teachings came from the cosmic Buddha Mahavairocana (Dainichi to the Japanese). Kukai brought these ideas to Japan and wrote such works as the Shorai Mokuroku ('A Memorial Presenting a List of Newly Imported Sutras'). Crucially, Shingon Buddhism proposed that an individual could achieve enlightenment in their own lifetime and need not wait for death. Rituals included meditation carried out while the body was held in various postures, sacred hand gestures ( mudras ), and the repetition of secret formulas or mantras. Great importance was given to the power of prayer.

In 819 CE the monk created a centre for his esoteric doctrine on Mount Koya (in the modern Wakayama Prefecture). Here educated devotees could reach enlightenment not by the lifelong study of sutras but by viewing mandalas, the stylised visual representation of the teachings of Buddha. In 823 CE Emperor Saga (r. 809-823 CE) granted the founding of the Toji('Eastern') temple at Minami-ku in Kyoto thus indicating that Shingon Buddhism had become an accepted part of the official state religion. In 921 CE, almost a century after his death, Kukai was given the posthumous title of Kobo Daishi, meaning 'Great Teacher of Spreading the Law', by the emperor.

Kukai

Saicho & Tendai Buddhism

Saicho was a monk who decided to live as an ascetic hermit on the slopes of Mount Hiei near Kyoto, and in 788 CE, he built the first shrine of what would later become the huge Enryaku-ji temple complex and centre of learning. He began to study all he could on every variation of Buddhism and to attract followers, including two of his best-known disciples - Ensho and Gishin.Saicho then visited Tang China in 804 CE, where he studied four branches of Buddhism including Zen and Tiantai. He was initiated into the higher levels of the faith, studied texts of Mikkyo (Esoteric Buddhism), and brought back with him over 200 manuscripts and various implements for use in esoteric rituals.

Saicho sought to simplify the teachings of Buddhism, and on his return, he founded the eclectic Tendai Sect ( Tendaishu ) which taught that the best and quickest way to reach enlightenment was through esoteric ritual, that is rites which only the priesthood and initiated had access to. At the same time, it allowed for many different ways to reach enlightenment. The Tendai branch of Buddhism was eventually given royal approval by Kammu, and Saicho performed the first esoteric rites in Japan to receive official sponsorship in 805 CE. On his death in 822 CE, Saicho, given the honorary title Dengyo Daishi, was also considered a bodhisattva, that is, one who has reached nirvana but remains on earth to guide others.

Tendai, perhaps inevitably given its broad range of eclectic beliefs, would, over the centuries, spawn other important Buddhist offshoots such as those of the Pure Land (Jodo) with the immensely popular figure of Amida, the universal Buddha, at its head, which was founded by the monk Honen (1133-1212 CE) and the Nichiren sect. Into the medieval period, more sects would come along, especially related to Zen Buddhism, and the faith would continue to be widely practised right up to the 15th century CE (when Shinto made something of a comeback) and, of course, it continues today to be a popular religion in modern-day Japan.

This article was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License