Ancient Greek Warfare › Ancient Greek Theatre › Chinese Lacquerware » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Ancient Greek Warfare › Origins

- Ancient Greek Theatre › Origins

- Chinese Lacquerware › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Ancient Greek Warfare › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

In the ancient Greek world, warfare was seen as a necessary evil of the human condition. Whether it be small frontier skirmishes between neighbouring city -states, lengthy city-sieges, civil wars, or large-scale battles between multi-alliance blocks on land and sea, the vast rewards of war could outweigh the costs in material and lives. Whilst there were lengthy periods of peace and many examples of friendly alliances, the powerful motives of territorial expansion, war booty, revenge, honour, and the defence of liberty ensured that throughout the Archaic and Classical periods the Greeks were regularly engaged in warfare both at home and abroad.

TOWARDS PROFESSIONAL WARFARE

Evolving from armed bands led by a warrior leader, city militia of part-time soldiers, providing their own equipment and perhaps including all the citizens of the city-state or polis, began to move warfare away from the control of private individuals and into the realm of the state. Assemblies or groups of elite citizens sanctioned war, and generals ( strategoi ) came to be accountable for their actions and were often elected for fixed terms or specific military operations.

WAR IS THE FATHER OF ALL AND KING OF ALL.HERACLEITUS FR. 53

In the early stages of Greek Warfare in the Archiac period, training was haphazard and even weapons could be makeshift, although soldiers were usually paid, if only so that they could meet their daily needs. There were no uniforms or insignia and as soon as the conflict was over the soldiers would return to their farms. By the 5th century BCE the military prowess of Spartaprovided a model for all other states to follow. With their professional and well-trained full-time army dressed in red cloaks and carrying shields emblazoned with the letter lambda (for Lacedaemonians), the Spartans showed what professionalism in warfare could achieve. Many states such as Athens, Argos, Thebes, and Syracuse began to maintain a small professional force ( logades or epilektoi ) which could be augmented by the main citizen body if necessary. Armies became more cosmopolitan with the inclusion of resident foreigners, slaves, mercenaries, and neighbouring allies (either voluntary or through compulsion in the case of Sparta's perioikoi ). Warfare moved away from one-off battles fought in a few hours to long-drawn-out conflicts which could last for years, the most important being the Persian Wars (first half of the 5th century BCE), the Peloponnesian Wars (459-446 & 431-404 BCE), and the Corinthian Wars (394-386 BCE).

Greek Hoplite

ARMIES, SOLDIERS, & WEAPONS

The mainstay of any Greek army was the hoplite. His full panoply was a long spear, short sword, and circular bronze shield and he was further protected, if he could afford it, by a bronze helmet (with inner padding for comfort), bronze breastplate, greaves for the legs and finally, ankle guards. Fighting was at close-quarters, bloody, and lethal. This type of warfare was the perfect opportunity for the Greek warrior to display his manliness ( andreia ) and excellence ( aretē ) and generals led from the front and by example.

To provide greater mobility in battle the hoplite came to wear lighter armour such as a leather or laminated linen corselet ( spolades ) and open-faced helmet ( pilos ). The peltast warrior, armed with short javelins and more lightly-armoured than the hoplite became a mobile and dangerous threat to the slower moving hoplites. Other lighter-armed troops ( psiloi ) also came to challenge the hoplite dominance of the battlefield. Javelin throwers ( akonistai ), archers ( toxotoi ) and slingers ( sphendonētai) using stones and lead bullets could harry the enemy with attacks and retreats. Cavalry ( hippeis ) was also deployed but due to the high costs and difficult terrain of Greece, only in limited numbers eg, Athens, possessing the largest cavalry force during the Peloponnesian Wars had only 1,000 mounted troops. Decisive and devastating cavalry offensives would have to wait until the Macedonians led by Philip and Alexander in the mid-4th century BCE.

FOR CENTURIES IT WAS THE HOPLITE WHO MONOPOLISED HONOUR ON THE GREEK BATTLEFIELD.

Armies also became more structured, spilt into separate units with hierarchies of command. The lochoi was the basic unit of the phalanx - a line of well-armed and well-armoured hoplite soldiers usually eight to twelve men deep which attacked as a tight group. In Athens the lochos was led by a captain ( lochagos ) and these combined to form one of ten regiments ( taxeis ) each led by a taxiarchos. A similar organisation applied to the armies of Corinth, Argos, and Megara. In 5th century Sparta the basic element was the enomotiai (platoon) of 32 men. Four of these made up a pentekostys (company) of 128 men. Four of these made up a lochos (regiment) of 512 men. A Spartan army usually consisted of five lochoi with separate units of non-citizen militia -- perioikoi. Units might also be divided by age or speciality in weaponry and, as warfare became more strategic, these units would operate more independently, responding to trumpet calls or other such signals mid-battle.

NAVAL WARFARE

Some states such as Athens, Aegina, Corinth, and Rhodes amassed fleets of warships, most commonly the trireme, which could allow these states to forge lucrative trading partnerships and deposit troops on foreign territory and so establish and protect colonies. They could even block enemy harbours and launch amphibious landings. The biggest fleet was at Athens, which could amass up to 200 triremes at its peak, and which allowed the city to build and maintain a Mediterranean-wide empire.

Trireme Ramming

The trireme was a light wooden ship, highly manoeuvrable and fitted with a bronze battering ram at the bow which could disable enemy vessels. Thirty-five metres long and with a 5 metre beam, some 170 rowers ( thetes - drawn from the poorer classes) sitting on three levels could propel the ship up to a speed of 9 knots. Also on board were small contingents of hoplites and archers, but the principal tactic in naval warfare was ramming not boarding. Able commanders arranged their fleets in a long front so that it was difficult for the enemy to pass behind ( periplous ) and ensure his ships were sufficiently close to prevent the enemy going through a gap ( diekplous ). Perhaps the most famous naval battle was Salamis in 480 BCE when the Athenians were victorious against the invading fleet of Xerxes.

However, the trireme had disadvantages in that there was no room for sleeping quarters and so ships had to be dry-docked each night, which also prevented the wood becoming water-logged. They were also fantastically expensive to produce and maintain; indeed the trireme was indicative that now warfare had become an expensive concern of the state, even if rich private citizens were made to fund most of the expense.

STRATEGIES

NOTHING EQUALS THE SHEER DELIGHT OF ROUTING, PURSUING AND KILLING AN ENEMY.XENOPHON, HIERO 2.15

The first strategy was actually employed before any fighting took place at all. Religion and ritual were important features of Greek life, and before embarking on campaign, the will of the gods had to be determined. This was done through the consultation of oracles such as that of Apollo at Delphi and through animal sacrifices ( sphagia ) where a professional diviner ( manteis ) read omens ( ta hiera ), especially from the liver of the victim and any unfavourable signs could certainly delay the battle. Also, at least for some states like Sparta, fighting could be prohibited on certain occasions such as religious festivals and for all states during the great Panhellenic games (especially those at Olympia ).

When all of these rituals were out of the way, fighting could commence but even then it was routine to patiently wait for the enemy to assemble on a suitable plain nearby. Songs were sung (the paian - a hymn to Apollo) and both sides would advance to meet each other. However, this gentlemanly approach in time gave way to more subtle battle arrangements where surprise and strategy came to the fore. What is more, conflicts also became more diverse in the Classical period with sieges and ambushes, and urban fighting becoming more common, for example at Solygeia in 425 BCE when Athenian and Corinthian hoplites fought house to house.

Strategies and deception, the 'thieves of war' ( klemmata ), as the Greeks called them, were employed by the more able and daring commanders. The most successful strategy on the ancient battlefield was using hoplites in a tight formation called the phalanx. Each man protected both himself and partially his neighbour with his large circular shield, carried on his left arm.Moving in unison the phalanx could push and attack the enemy whilst minimising each man's exposure. Usually eight to twelve men deep and providing the maximum front possible to minimise the risk of being outflanked, the phalanx became a regular feature of the better trained armies, particularly the Spartans. Thermopylae in 480 BCE and Plataea in 479 BCE were battles where the hoplite phalanx proved devastatingly effective.

Greek Phalanx

At the Battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE Theban general Epaminondas greatly strengthened the left flank of his phalanx to about 50 men deep which meant he could smash the right flank of the opposing Spartan phalanx, a tactic he used again with great success at Mantineia in 362 BCE. Epaminondas also mixed lighter armed troops and cavalry to work at the flanks of his phalanx and harry the enemy. Hoplites responded to these developments in tactics with new formations such as the defensive square ( plaision ), used to great effect (and not only in defence) by Spartan general Brasidas in 423 BCE against the Lyncestians and again by the Athenians in Sicily in 413 BCE. However, the era of heavily armoured hoplites neatly arranged in two files and slashing away at each other in a fixed battle was over. More mobile and multi-weapon warfare now became the norm. Cavalry and soldiers who could throw missiles might not win battles outright but they could dramatically affect the outcome of a battle and without them the hoplites could become hopelessly exposed.

SIEGES

From an early stage most Greek city-states had a fortified acropolis (Sparta and Elis being notable exceptions) to protect the most important religious and civic buildings and provide refuge from attack. However, as warfare became more mobile and moved away from the traditional hoplite battle, cities sought to protect their suburbs with fortification walls. Independent lookout towers in the surrounding countryside and even frontier forts and walls sprang up in response to the increased risk of attacks. Many poleis also built fortifications to create a protective corridor between the city and their harbour, the most famous being the Long Walls which spanned the 7 km between Athens and Piraeus.

Sieges were usually long-drawn out affairs with the principal strategy being to starve the enemy into submission. Offensive strategies using battering rams and ramps proved largely unsuccessful. However, from the 4th century BCE technical innovations gave the attackers more advantages. Wheeled siege towers, first used by the Carthaginians and copied by Dionysius I of Syracuse against Motya in 397 BCE, bolt-throwing artillery ( gastraphetes ), stone throwing apparatus ( lithoboloi) and even flame-throwers (at Delion in 424 BCE) began a trend for commanders to be more aggressive in siege warfare.However, it was only with the arrival of torsion artillery from 340 BCE, which could propel 15 kg stones over 300 metres, that city walls could now be broken down. Naturally, defenders responded to these new weapons with thicker and stronger walls with convex surfaces to better deflect missiles.

Greek Warriors Stele

LOGISTICS

The short duration of conflicts in the Greek world was often because of the poor logistics supplying and maintaining the army in the field. Soldiers were usually expected to provide their own rations (dried fish and barley porridge being most common) and the standard for Athens was three-days' worth. Most hoplites would have been accompanied by a slave acting as a baggage porter ( skeuophoroi ) carrying the rations in a basket ( gylion ) along with bedding and a cooking pot. Slaves also acted as attendants to the wounded as only the Spartan army had a dedicated medical officer ( iatroi ). Fighting was usually in the summer so tents were rarely needed and even food could be pillaged if the fighting was in enemy territory. Towards the end of the Classical period armies could be re-supplied by ship and larger equipment could be transported using wagons and mules which came under the responsibility of men too old to fight.

VICTOR'S SPOILS

...LET HIM KILL HIS ENEMY AND BRING HOME THE BLOODIED SPOILS, AND DELIGHT THE HEART OF HIS MOTHER.HEKTOR'S PRAYER TO HIS SON, ILIAD 6.479-81

War booty, although not always the primary motive for conflict, was certainly a much-needed benefit for the victor which allowed him to pay his troops and justify the expense of the military campaign. Booty could come in the form of territory, money, precious materials, weapons, and armour. The losers, if not executed, could expect to be sold into slavery, the normal fate for the women and children of the losing side. It was typical for 10% of the booty (a dekaten ) to be dedicated in thanks to the gods at one of the great religious sanctuaries such as Delphi or Olympia. These sites became veritable treasuries and, effectively, museums of weapons and armour. They also became too tempting a target for more unscrupulous leaders in later times, but still the majority of surviving military material comes from archaeological excavations at these sites.

Corinthian Helmet

Important rituals had to be performed following victory which included the recovering of the dead and the setting up of a victory trophy (from tropaion, meaning turning point in the conflict) at the exact place on the battlefield where victory became assured.The trophy could be in the form of captured weapons and armour or an image of Zeus ; on occasion memorials to the fallen were also set up. Speeches, festivals, sacrifices and even games could also be held following a victory in the field.

CONCLUSION

Greek warfare, then, evolved from small bands of local communities fighting for local territory into massive set-piece battles between multi-allied counterparts. War became more professional, more innovative, and more deadly, reaching its zenith with the Macedonian leaders Philip and Alexander. Learning from the earlier Greek strategies and weapons innovations, they employed better hand weapons such as the long sarissa spear, used better artillery, successfully marshalled diverse troop units with different arms, fully exploited cavalry, and backed all this up with far superior logistics to dominate the battlefield not only in Greece but across vast swathes of Asia and set the pattern for warfare through Hellenistic and into Roman times.

Ancient Greek Theatre › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Greek theatre began in the 6th century BCE in Athens with the performance of tragedy plays at religious festivals. These, in turn, inspired the genre of Greek comedy plays. The two types of Greek drama would be hugely popular and performances spread around the Mediterranean and influenced Hellenistic and Roman theatre. Thus the works of such great playwrights as Sophocles and Aristophanes formed the foundation upon which all modern theatre is based.

THE ORIGINS OF TRAGEDY

The exact origins of tragedy ( tragōida ) are debated amongst scholars. Some have linked the rise of the genre to an earlier art form, the lyrical performance of epic poetry. Others suggest a strong link with the rituals performed in the worship of Dionysossuch as the sacrifice of goats - a song ritual called trag-ōdia - and the wearing of masks. Indeed, Dionysos became known as the god of theatre and perhaps there is another connection - the drinking rites which resulted in the worshippers losing full control of their emotions and in effect becoming another person, much as actors ( hupokritai ) hope to do when performing.The music and dance of Dionysiac ritual was most evident in the role of the chorus and the music provided by an aulos player, but rhythmic elements were also preserved in the use of first, trochaic tetrameter and then iambic trimeter in the delivery of the spoken words.

A TRAGEDY PLAY

Plays were performed in an open-air theatre ( theatron ) with wonderful acoustics and seemingly open to all of the male populace (the presence of women is contested). From the mid-5th century BCE entrance was free. The plot of a tragedy was almost always inspired by episodes from Greek mythology, which we must remember were often a part of Greek religion.As a consequence of this serious subject matter, which often dealt with moral right and wrongs and tragic no-win dilemmas, violence was not permitted on the stage, and the death of a character had to be heard from offstage and not seen. Similarly, at least in the early stages of the genre, the poet could not make comments or political statements through his play.

DUE TO THE RESTRICTED NUMBER OF ACTORS EACH PERFORMER HAD TO TAKE ON MULTIPLE ROLES WHERE THE USE OF MASKS, COSTUMES, VOICE & GESTURE BECAME EXTREMELY IMPORTANT.

The early tragedies had only one actor who would perform in costume and wear a mask, allowing him to impersonate gods.Here we can see perhaps the link to earlier religious ritual where proceedings might have been carried out by a priest. Later, the actor would often speak to the leader of the chorus, a group of up to 15 actors (all male) who sang and danced but did not speak. This innovation is credited to Thespis c. 520 BCE (origin of the word thespian). The actor also changed costumes during the performance (using a small tent behind the stage, the skēne, which would later develop into a monumental façade) and so break the play into distinct episodes. Later, these would develop into musical interludes. Eventually, three actors were permitted on stage but no more - a limitation which allowed for equality between poets in competition. However, a play could have as many non-speaking performers as required, so that plays with greater financial backing could put on a more spectacular production. Due to the restricted number of actors then, each performer had to take on multiple roles where the use of masks, costumes, voice, and gesture became extremely important.

COMPETITION & CELEBRATED PLAYWRIGHTS

The most famous competition for the performance of tragedy was as part of the spring festival of Dionysos Eleuthereus or the City Dionysia in Athens. The archon, a high-ranking official of the city, decided which plays would be performed in competition and which citizens would act as chorēgoi and have the honour of funding their production while the state paid the poet and lead actors. Each selected poet would submit three tragedies and one satyr play, a type of short parody performance on a theme from mythology with a chorus of satyrs, the wild followers of Dionysos. The plays were judged on the day by a panel, and the prize for the winner of such competitions, besides honour and prestige, was often a bronze tripod cauldron. From 449 BCE there were also prizes for the leading actors ( prōtagōnistēs ).

Theatre of Dionysos Eleuthereus, Athens

Playwrights who regularly wrote plays in competition became famous, and the three most successful were Aeschylus (c. 525 - c. 456 BCE), Sophocles (c. 496-406 BCE), and Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE). Aeschylus was known for his innovation, adding a second actor and more dialogue, and even creating sequels. He described his work as 'morsels from the feast of Homer ' (Burn 206). Sophocles was extremely popular and added a third actor to the performance as wells as painted scenery.Euripides was celebrated for his clever dialogues, realism, and habit of posing awkward questions to the audience with his thought-provoking treatment of common themes. The plays of these three were re-performed and even copied into scripts for 'mass' publication and study as part of every child's education.

GREEK COMEDY - ORIGINS

The precise origins of Greek comedy plays are lost in the mists of prehistory, but the activity of men dressing as and mimicking others must surely go back a long way before written records. The first indications of such activity in the Greek world come from pottery, where decoration in the 6th century BCE frequently represented actors dressed as horses, satyrs, and dancers in exaggerated costumes. Another early source of comedy is the poems of Archilochus (7th century BCE) and Hipponax (6th century BCE) which contain crude and explicit sexual humour. A third origin, and cited as such by Aristotle, lies in the phallic songs which were sung during Dionysiac festivals.

A COMEDY PLAY

Although innovations occurred, a comedy play followed a conventional structure. The first part was the parados where the Chorus of as many as 24 performers entered and performed a number of song and dance routines. Dressed to impress, their outlandish costumes could represent anything from giant bees with huge stingers to knights riding another man in imitation of a horse or even a variety of kitchen utensils. In many cases the play was actually named after the Chorus, eg, Aristophanes' The Wasps.

Greek Comedy Mask

The second phase of the show was the agon which was often a witty verbal contest or debate between the principal actors with fantastical plot elements and the fast changing of scenes which may have included some improvisation. The third part of the play was the parabasis, when the Chorus spoke directly to the audience and even directly spoke for the poet. The show-stopping finale of a comedy play was the exodos when the Chorus gave another rousing song and dance routine.

As in tragedy plays, all performers were male actors, singers, and dancers. One star performer and two other actors performed all of the speaking parts. On occasion, a fourth actor was permitted but only if non-instrumental to the plot. Comedy plays allowed the playwright to address more directly events of the moment than the formal genre of tragedy. The most famous comedy playwrights were Aristophanes (460 - 380 BCE) and Menander (c. 342-291 BCE) who won festival competitions just like the great tragedians. Their works frequently poked fun at politicians, philosophers, and fellow artists, some of whom were sometimes even in the audience. Menander was also credited with helping to create a different version of comedy plays known as New Comedy (so that previous plays became known as Old Comedy). He introduced a young romantic lead to plays, which became, along with several other stock types such as a cook and a cunning slave, a popular staple character. New Comedy also saw more plot twists, suspense, and treatment of common people and their daily problems.

LEGACY

New plays were continuously being written and performed, and with the formation of actors' guilds in the 3rd century BCE and the mobility of professional troupes, Greek theatre continued to spread across the Mediterranean with theatres becoming a common feature of the urban landscape from Magna Graecia to Asia Minor. In the Roman world plays were translated and imitated in Latin, and the genre gave rise to a new art form from the 1st century BCE, pantomime, which drew inspiration from the presentation and subject matter of Greek tragedy. Theatre was now firmly established as a popular form of entertainment and it would endure right up to the present day. Even the original 5th-century BCE plays have continued to inspire modern theatre audiences with their timeless examination of universal themes as they are regularly re-performed around the world, sometimes, as at Epidaurus, in the original theatres of ancient Greece.

Chinese Lacquerware › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

Lacquer was a popular form of decoration and protective covering in ancient China. It was used to colour and beautify screens, furniture, bowls, cups, sculpture, musical instruments, and coffins, where it could be carved, incised, and inlaid to show off scenes from nature, mythology, and literature. Time-consuming to produce, Chinese lacquerware became highly sought after by those who could afford it and by neighbouring cultures.

MATERIALS & TECHNIQUES

Lacquerware describes objects made of wood, metal, or just about anything similar which have been covered in a liquid made of shellac or melted resin flakes dissolved in alcohol (or a synthetic substance), which forms a hard protective smooth coating when dry which remains relatively light in weight. The ancient Chinese artists used the sap of the tree Rhus vernicefera ( Toxicodendron vernicifluum ), which was native to eastern and southern China and was sometimes referred to as the 'Lacquer Tree'. The resin is drained from a cut in the living tree and becomes an opaque white liquid on contact with the air. Lacquer existed in many colours by adding certain chemicals to the resin, for example, black was made by adding carbon, yellow by adding ochre, and a brilliant red was achieved by mixing in mercuric sulphide (aka cinnabar). These were the three most popular colours in ancient Chinese lacquer painting.

Han Lacquered Bowl

The resulting lacquer, when dried slowly in humid conditions, is remarkably resistant to heat, damp, and chemicals. For this reason, lacquer was often used to coat and protect goods of more perishable material which might be easily damaged such as bamboo, silk, and wood. Lacquer can quickly degrade, though, if it cracks, and this has led to a scarcity of finds in ancient tombs and other buried contexts.

LACQUER CAN BE USED TO COVER, PROTECT & DECORATE ALMOST ANY TYPE OF SURFACE, UNEVEN OR OTHERWISE.

As the lacquer is very thin when applied it requires many coats to provide an even finish, but an advantage is that the lacquer can be used to cover almost any type of surface, uneven or otherwise. The preceding coat must be absolutely dry and be highly polished before applying the next one, with some objects having as many as 100 such layers, illustrating that the production of lacquerware was a time-consuming and expensive business.

By the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) a new technique became popular where a wooden or textile base material was repeatedly covered in lacquer until it was thick enough to be sculpted and carved. If different colours of lacquer were used in different applied layers then cutting through them could reveal the contrasting colours to pick out designs. Another effect was to have the surface and lowest level of lacquer in the same colour but have the sides of the cut display a marble effect from the use of different coloured intermediate layers.

Chinese Lacquered Guardian Figure

The Guri technique creates schematic scroll designs by cutting through layers of different colours, and the deep cuts are often bevelled. Sometimes fine gold wiring or leaf was used as an inlay in carved lacquer or studs of semi-precious material such as turquoise, mother-of-pearl and ivory were pressed into the surface. Intricate linear and floral designs, images of humans, animals, birds and mythical creatures, and even sculpted landscape scenes were thus rendered in lacquer. Although great artistry was employed in lacquerware, it was not common for pieces to be signed by the artist until the 14th century CE.

LACQUERWARE EVOLUTION

The earliest Chinese lacquerware yet discovered dates to the Late Neolithic period (3rd millennium BCE) and comes from the Hemudu site in a waterlogged area of the lower Yangtse region which has preserved many such artefacts. Production of lacquerware continued into the Bronze Age of the 2nd millennium BCE when it began to be traded to other areas of China which did not have the Rhus vernicefera tree.

From the 5th century BCE and the Warring States Period lacquer production greatly intensifies and even small-scale burials have some lacquerware - typically cups and bowls - placed in them while larger tombs can have hundreds of examples. This suggests that production scale had increased and the product had become affordable to even those with a modest income.The artists of the Chu state were particularly imaginative and produced distinctive lacquered sculptures of mythical creatures which may have acted as tomb guardians.

Han Lacquered Box

By the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) lacquer was being used on cups, bowls, small boxes, figure sculpture, musical instruments and their stands, bows (to make the wood and bindings waterproof), wooden wall panels showing narrative scenes, and fans. During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) the state sponsored and supervised the production of lacquerware which now had different schools of lacquer art producing common forms but with recognisably distinct designs.

THE MOST COMMON FORMS OF LACQUERWARE ARE CUPS, BOWLS, BOXES, & STATUES.

LACQUERWARE FORMS

The most common lacquered goods were shallow stemmed cups (circular or oval) with varieties of handles, cups shaped into birds, beakers, and bowls (sometimes with winged rims) which often imitated the decorative designs seen in contemporary bronze work and embroidery. Typical motifs include lozenge patterns, monsters, stylistic dragons, circles, close spirals, zig-zags, triangles and curved lines and asymmetrical shapes to fill the blank areas in-between. Small lacquered boxes were also popular and could be round, rectangular or L-shaped. A third main group in the lacquer artist's armoury was wooden animal sculptures depicting tigers, deer, peacocks, cranes, and monsters with antlers and protruding tongues, amongst others.Statues of Buddhist figures which appeared in temples would come to be lacquered, too, especially during the Tang Dynasty.

Paper or wooden screens were an ideal medium for the lacquer worker. Painted on both sides with scenes and sometimes also with extracts from famous texts, they were used not only to divide living space in private homes but also in tombs to surround the coffin of the deceased. One such example is from the tomb of Sima Jinlong, a Tuoba ruler of Wei, the northern Chinese state, who died in 484 CE. The lacquered screen was divided into four sections arranged vertically and had scenes and text from the 1st-century BCE Lienu zhuan ('Biographies of Exemplary Women'). The screen is 80 cm high (it was not necessary for screens to be taller because people then sat on mats on the floor) and has the figures and text in yellow on a bright red background.

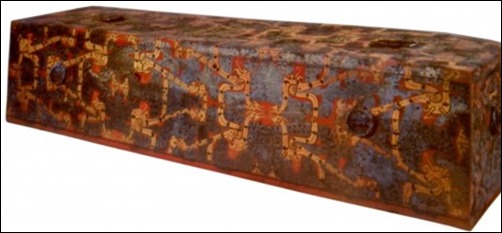

Chinese Lacquered Coffin

Ataúdes para los que podían pagarlos se barnizan y un ejemplo sobresaliente proviene de la tumba cuarto siglo BCE en Baoshan en la provincia de Hubei. El ataúd rectangular fue la más interna de tres y se cubre completamente en laca negro con 72 representaciones amarillo y rojo de serpientes dragón interconectados y un número similar de aves míticas. En la actualidad se encuentra en exhibición en el Museo Provincial de Hubei, China.

Instrumentos musicales fueron lacado tanto para protegerlos y para agregar la decoración. Una famosa pipa, un tipo de laúd, desde el siglo octavo CE tiene una pintura de paisaje budista con las montañas y los ríos. Se cree que es uno de los más antiguos tales representaciones. El instrumento está ahora en Shosoin, Nara, Japón y es uno de los muchos elementos dados como regalos o negociados e ilustra el gran atractivo de laca china en Asia Oriental.

Pequeñas piezas de mobiliario como mesas bajas eran frecuentemente lacado y tallados con diseños decorativos. Un excelente ejemplo, aunque tarde (dinastía Ming, CE del siglo 15a), es una tabla de laca tallada rojo que cubre un núcleo de madera, que se encuentra ahora en el Victoria and Albert Museum de Londres. Las técnicas de trabajo de la laca no cambió durante los siglos pero artistas posteriores hizo finalmente llegan a ser más ambicioso, y por la Ming y Qing (1644-1912 dC) enormes escenas estaban siendo talladas en relieve alto y preciso con muchos niveles diferentes de perspectiva.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License