Enemies of Rome in the 3rd Century CE » Adad Nirari I » Adonis » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions » Contents

- Enemies of Rome in the 3rd Century CE » Origins

- Adad Nirari I » Who was

- Adonis » Who was

Ancient civilizations » Historical places, and their characters

Enemies of Rome in the 3rd Century CE » Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

It has been said that the greatest enemy of Rome was Rome itself, and this is certainly true of the period known as the Crisis of the Third Century (also known as the Imperial Crisis, 235-284 CE). During this time of almost 50 years, over 20 different emperors ruled in quick succession; a statistic which becomes more alarming when compared with the 26 who reigned between 27 BCE and 235 CE. These rulers – known as the “barracks emperors” because they were supported by and largely came from the army – were generally motivated by their own ambition and personal interests and so served themselves before the interests of the state.

Although a few of these emperors proved themselves worthy of rule, they could not escape the climate of the times which rewarded direct and discernible results on the part of leadership, even if those results were not always in the people’s best interest. The Crisis of the Third Century began when the emperor Alexander Severus (222-235 CE) decided to pay the German tribes for peace instead of meeting them in battle and his troops, considering this course dishonorable, killed him. Such an action against a sitting emperor would have been considered unthinkable in the past but became so commonplace during this period that elevating a man to the position of emperor was almost a death sentence.

Valerian Defeated by Shapur I

After the death of Alexander Severus, a new paradigm for a ruler became standard – of emperors relying on the goodwill of the military in general and their own commands specifically – and this would characterize the whole of the period. Emperors could no longer rule according to their vision of the best version of Rome; they now had to make policy with their popularity among the army in mind.

At this same time, when Rome was, for the most part, lacking strong leadership, suffering plague, inflation, and other domestic difficulties, external threats presented themselves in the form of so-called “barbarian tribes” and others who either sought to topple Rome or simply remove themselves from the confusion and disorder which had come to characterize the Roman Empire. Chief among Rome’s enemies during this period were:

• King Cniva of the Goths (and later King Cannabaudes, claimed by some scholars as the same man c. 251-270? CE)

• King Shapur I (240-270 CE) of the Sassanid Persians as well as his son, Hormizd I (270 - c. 273)

• Postumus of the Gallic Empire (260-269 CE) and those who ruled after him (Marius, Victorinus, Domitianus, and Tetricus I), most notably Tetricus I (271-274 CE)

• Zenobia of the Palmyrene Empire (267-272 CE) and her Egyptian general Zabdas (c. 267- c. 273 CE)

All of these rulers played a part in the crisis which beset Rome in the 3rd century CE. Cniva was the first barbarian king to kill a sitting emperor in battle; Shapur I was the first to capture one; Postumus was a Roman governor who decided he could do better creating his own empire, and Queen Zenobia of Palmyra did the same.

SPONSORSHIP MESSAGE

This article was sponsored by Total War™

Empire Divided is a new campaign pack for Total War: ROME II, focused on the Crisis of the Third Century. Can you restore the Roman Empire to its former glory or will you tear it down? Play from the 30th of November 2017.GET THE GAME

From 235 CE until Emperor Aurelian came to power in 270 CE there were very few Roman leaders capable of meeting these threats. At war with each other, and surrounded by pressing challenges, most of the emperors of the 3rd century CE failed the state and the people they were supposed to protect and lead.

Many of the problems they faced were not at all new; what made them seem so was the inability of the emperor to resolve any of them. The vast scope of the empire at this time, which made the old model of rule by one emperor obsolete, and an inability to imagine one more effective and practical, left Rome in a position of weakness, where any man promising results was elevated at the expense – and life – of his predecessor.

Due to the various emperors’ failings – as well as other serious problems with the bureaucracy and general function of the Roman state – adversaries like Cniva and Shapur I, as well as former friends like Postumus and Zenobia – were able to gain significant advantages and, in the case of the latter two, even form their own empires.

CNIVA

Cniva (also given as Kniva) was the king of the Goths who defeated the emperor Decius at the Battle of Abritus in 251 CE. Scholar Michael Grant observes that “in Kniva the Goths had a leader of unprecedented caliber, whose large-scale strategy created the gravest perils the empire had yet undergone” (31). Cniva may have learned his strategies through service in the Roman army or may have simply been a careful observer of his adversary. Little is known of him outside of his campaign in 251 CE in which he lay siege to the Roman city of Nicopolis and successfully took Philipopolis, killing over one hundred thousand Roman citizens and enslaving survivors.

CNIVA MAY HAVE LEARNED HIS STRATEGIES THROUGH SERVICE IN THE ROMAN ARMY OR MAY HAVE SIMPLY BEEN A CAREFUL OBSERVER OF HIS ADVERSARY.

Emperor Decius was driven from the field by Cniva once and, when he regrouped and attacked again, Cniva had all the advantages. Cniva knew the terrain, was able to position his troops effectively, and lured Decius and his army into the marshy ground of a swamp. The Roman formations were rendered ineffective on this ground, and Cniva slaughtered most of them, including Decius and his son. Afterwards, the Romans had no choice but to allow Cniva to go on his way with his many prisoners and all the treasures of Philipopolis.

After the Battle of Abritus, Cniva is not heard from again but is associated with the later King Cannabaudes (also given as Cannabas, c. 270 CE) of the Goths, who was killed in battle, along with 5,000 of his troops, in an engagement with Aurelian (270-275 CE) in c. 270 CE. It would not be impossible for the same man to have led the Goths in 251 and in 270 CE. The Battle of Naissus (268 or 269 CE) pit the emperor Claudius II against a Gothic force led by an unnamed king who could have been Cniva.

Whether Cniva was the same leader as Cannabaudes, his ability to strategize and his skills in warfare were not handed down to the next generation. The identification of Cniva with Cannabaudes makes sense in that, according to reports, the Gothic king was killed along with 5,000 of his men and the secrets of his success would thus have been lost with those soldiers who had planned and fought with him. After Cniva’s successes, there are no other reports of Goths taking Roman cities by siege nor in any other manner. The later Gothcommander Fritigern (c. 380 CE) famously avoided engagements involving cities, preferring guerilla warfare tactics.

SHAPUR I & HORMIZD I

In the east, however, there was another ruler who had no such problem: Shapur I. Shapur I was the son of Ardashir (224-242 CE), the founder of the Sassanian dynasty, who elevated Shapur I to co-ruler and instructed him in warfare. Although Shapur I was an able administrator and ruler whose reign is recorded in glowing phrases by everyone except Roman writers, he thought of himself as a warrior-king first and tried to embody this ideal.

Roman Coin of Philip the Arab

Shapur I continued his father’s policies of aggression toward Rome and took Roman fortresses and cities in Mesopotamiaearly in his reign. He was met in battle by the emperor Gordian III, who was only 17 years old at the time, and who relied heavily on the advice and strategies of his father-in-law and Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Timesitheus. Shapur I was driven back by the Roman forces at first, but when Timesitheus died of the plague the situation reversed; Gordian III had little military experience and lacked the skill to counter Shapur I’s strategies. When Gordian III failed to meet the expectations of his troops, they killed him, and he was replaced by Philip the Arab.

Philip quickly made peace with Shapur I and paid him 500,000 denars as part of the treaty. Philip ceded the disputed territory of Armenia to Shapur I, who sent his son Hormizd I (who had fought with him against the Romans) to rule it. Hormizd I ruled well as viceroy of Armenia, maintaining his father’s policies regarding freedom of religion and establishing a peaceful and prosperous reign. An able administrator, as well as a courageous and skilled warrior, Hormizd I was widely respected for his initiatives in the short time he ruled over Armenia. Fairly quickly, however, Philip discarded the treaty and reclaimed the region; this action obviously broke the peace and plunged the region back into war.

Shapur I ravaged through Mesopotamia and conquered the Roman province of Syria, taking the city of Antioch. Hormizd I accompanied his father on this campaign and held important positions of command and administration throughout the course of it. The emperor Valerian marched against Shapur I and Hormizd I and drove them from the city, but in the course of pursuit, the plague struck the Roman army and they had to withdraw back into Antioch.

Hormizd I in Battle

Shapur I and Hormizd I lay siege to the city and Valerian had no choice but to seek terms. He and his senior staff went out to meet the Persian leaders to discuss the city’s surrender but were taken captive instead and the city fell to the Sassanid forces. According to legend, Shapur I used Valerian as a footstool to mount his horse and, when the emperor died, had his body stuffed with straw and put on display.

Thus far, Shapur I’s instincts, skill, and simple good fortune had brought him close to realizing his ambition of conquering all the eastern Roman provinces, but at this point, he made a grave mistake. Odaenthus, the Roman governor of the Syrian city of Palmyra, wrote Shapur I an offer of alliance; Shapur I rejected this in the clearest terms possible.

In the chaos which characterized the 3rd century in Rome, Odaenthus was probably hoping for some semblance of order for his home region and Shapur I would have seemed a better choice than any of the Roman emperors. Shapur I rebuffed the offer, stating that Odaenthus was nowhere near his equal and should look forward to becoming his vassal. Odaenthus, insulted and enraged, then mobilized a force and drove Shapur I out of Roman territory.

Defeat of Valerian by Shapur

Shapur I’s victory over Valerian was among his last. Odaenthus defeated the Sassanid Persians in every encounter. Regarding this, scholar Philip Matyszak observes how Shapur I “discovered that a well-led Roman army was still the world’s finest fighting force” (239). After Odaenthus’ campaigns, Shapur I lost any gains he had made and retreated back to his own borders. The rest of his reign focused chiefly on domestic issues while keeping a wary peace with Rome. When he died, he was succeeded by Hormizd I who continued his policies, resulting in a kind of cold war between the Sassanids and Rome. Hormizd I made no overt hostile gestures toward Rome but certainly offered no sign of cordial relations between the two states.

Odaenthus, having beaten back the Persian threat, was rewarded by Emperor Gallienuswith greater power and authority as governor of all of Rome’s eastern provinces. He was killed while hunting in 267/268 CE, and his wife, Queen Zenobia, took over as regent for their young son Vaballathus. Soon, however, it would be clear that Zenobia had grander plans than simply place-holding for another.

ZENOBIA & POSTUMUS

Zenobia inherited Odaenthus’ territory as well as his army and their brilliant Egyptian general Zabdas. Although careful not to antagonize the Roman emperor Gallienus, or show herself officially in any light other than as an acceptable Roman regent, she expanded her territory and entered into negotiations without Rome’s consent. In every way but official title, she reigned as supreme empress over the eastern regions of what had been the Roman Empire.

One of her most impressive moves was against Roman Egypt. Egypt was Rome’s breadbasket, supplying the empire with grain, and was among its most prized provinces. Zenobia sent Zabdas to Egypt to put down a revolt – which she most likely instigated to give herself just cause – and then annexed the country. Officially, she could claim that this action was in Rome’s best interest and she had only been keeping the peace, but she acted without consulting the emperor, and her annexation of Egypt certainly elevated her reputation at Rome’s expense.

She also issued her own currency, gave herself and her son royal titles reserved for the emperor and his family, and entered into negotiations with the Sassanid Persians. All of these initiatives strengthened her position as empress of her own realm, but if Rome objected, she could justify each one as being for Rome’s benefit.

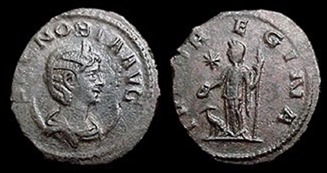

Zenobia Denarius

At the same time Zenobia was consolidating her power in the east, another former friend of Rome, and a sitting provincial governor, did the same in the west. Postumus was the Roman governor of Upper and Lower Germany under the co-rule of Gallienus and Valerian. Postumus had already defended the provinces in the west from barbarian incursions and felt he needed more power and authority to perform his duties more efficiently. Valerian was fighting in the east and Gallienus was busy with his own campaigns in the west and north. Frustrated by the inability to do what he felt he should, Postumus marched on the Roman city of Cologne, where the son and heir of Gallienus had been sent for his own safety, and killed him as well as his bodyguard.

Postumus then declared himself emperor of his own realm – the Gallic Empire – which comprised Germany, Gaul, Hispania, and Britannia. He set up his own senate, mobilized his own troops, and entered into his own negotiations but insisted, all the while, that he was acting in Rome’s interests. After Valerian was captured by Shapur I, Postumus grew bolder and Gallienus made time from his campaigns to launch an attack on the Gallic Empire but was driven back. Gallienus was killed by his own troops shortly after this event, and Claudius Gothicus and then his brother Quintillus were emperor before Aurelian took power.

AURELIAN’S RESTORATION & TETRICUS I

Aurelian was a soldier, not a politician, and had neither the time nor the patience for inquiries into why Zenobia or Postumus had acted as they did. As soon as he had defeated the Goths (killing Cannabaudes/Cniva), as well as the Vandals, Jugunthi, Alammani, and others, he marched on the Palmyrene Empire. At the Battle of Immae in 272 CE he had his cavalry engage and then feign retreat in a rout, and when the Palmyrene cavalry pursued, he led them into a trap in which his forces wheeled about and drove into the opposing forces, killing most of them and scattering the rest.

Immae was a stunning victory for Aurelian, but Zenobia and Zabdas escaped and reformed their troops against him. At the Battle of Emessa, using the same tactic he had at Immae, Aurelian defeated Zenobia’s forces and Zabdas was probably killed; he is not mentioned in any later reports. Zenobia, after trying to escape again, was caught and brought to Rome. Aurelian showed mercy to Palmyra and many of the ringleaders of the Palmyrene Empire, but when the city rebelled a second time, he hurriedly returned and destroyed it, massacring the inhabitants.

Queen Zenobia before Emperor Aurelianus

After taking care of Palmyra, Aurelian marched west for the Gallic Empire. Postumus was dead by this time, killed by his own troops in 269 CE when he tried to prevent them from sacking the Roman city of Mainz which had rebelled. The position of emperor had passed to others (Marius, Victorinus, and Domitianus) before Tetricus I was nominated by Victorinus’ mother.

Postumus had been an able administrator and commander, but Marius, Victorinus, and Domitianus were much weaker and far less effective. Marius was a blacksmith and possibly a foot soldier who was chosen by the troops at Mainz, most likely because he led the opposition to Postumus’ command to spare the city. He was only in power briefly before being assassinated. Victorinus, a Praetorian tribune, then became emperor and although he was an able military leader, he could not control his lust for women. He was murdered after trying to seduce the wife of one of his commanders. The usurper Domitianus then seized power but was overthrown by Tetricus I. Tetricus I is considered the only true successor to Postumus owing to his personal character and his strong military and administrative skills.

After the assassination of Postumus, Hispania left the Gallic Empire and declared their allegiance to Rome. At this same time, more German tribes rebelled against the Gallic rule from Trier. Victorinus had attempted to control these revolts with more or less success but was not able to restore stability to the region. This was the volatile situation Tetricus I inherited when he became emperor. He made his son (also named Tetricus) his co-emperor in order to share the burden of responsibility for the military and government administration and then went to work to restore the empire. He put down the rebellions and stabilized Germania and Gaul but any further initiatives were halted when word came that Aurelian had defeated Zenobia and was coming for the Gallic Empire next.

Tetricus I

When Tetricus I heard that Aurelian was marching against him, he allegedly sent him a letter asking the emperor to save him and his son and offering to surrender. Much debate has gone on surrounding this allegation, and it is thought by some scholars to be a later invention of Aurelian to discredit Tetricus I by accusing him of betraying his troops to save himself. It is clear that Tetricus I was an able leader and was popular among his troops; it seems unlikely he would have brokered a deal to surrender before battle while still committing his army to the field.

Whether Tetricus I made such a deal with Aurelian or not, the Roman forces slaughtered those of the Gallic Empire at the Battle of Chalons in 274 CE, and Tetricus I and his son were taken captive. They were spared, as were other officials in the Gallic government, which gave rise to the rumors that he had betrayed his troops. Tetricus I was given an administrative office in a Roman province (as was his son) and, just like Zenobia, lived comfortably for the rest of his life. Aurelian had now restored the empire but would not live much longer to enjoy his accomplishments.

Aurelian had defeated the Goths as well as a number of other invading tribes, kept the Persians at bay, brought both the Gallic and Palmyrene empires back into the Roman fold, and reformed abuses of the mint at Rome, thus stabilizing the currency. Aurelian’s reign shows every indication of continuing on this trajectory toward reform and restoration, but it was cut short by those he mistakenly believed he could trust. In keeping with the spirit of the times, even a great emperor like Aurelian could not finally triumph over his own people, and he was killed by his commanders who mistakenly believed he was planning to execute them.

ROME’S GREATEST ENEMY

Even though Rome had many enemies throughout the 3rd century CE, the greatest threat to its continued existence was itself. The problems Rome faced at this time, as noted earlier, were not new – there were invasions and internal difficulties decades and even centuries earlier – what was new was Rome’s inability to deal with these issues. A lack of patience and policy defined the period of 3rd-century CE Rome, and many decisions were made based on fear rather than hope.

This climate invited problems from external sources like the Goths and the Sassanid Persians and others and encouraged leaders like Zenobia and Postumus to create their own empires, but these kinds of situations would have once been dealt with decisively and swiftly. In the 3rd century CE, they were handled inefficiently or not at all until the reign of Aurelian.

It is in this way that Rome was its own greatest enemy during this period. By the time of the 3rd century CE the corruption of the state, the decline in a moral and social paradigm once provided by the pagan religion, and the migration of other peoples across and around the borders of the empire all led to imperial decisions made in the interests of immediate and popular results. The external enemies of Rome were certainly a very real threat, but on a certain level, their victories were simply manifestations of the decay of what was once the Roman Empire.

Adad Nirari I » Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Adad Nirari I (reigned 1307-1275 BCE) was the king of the Assyrian Empire who initiated the first major expansion of the Assyrian kingdom from the city of Ashur throughout the region of Mesopotamia. He also instituted what would become standard Assyrian procedure: relocating large segments of the population in conquered regions. Adad Nirari I ruled during the period known to modern-day scholars as the Middle Empire and expanded the borders significantly. He is best known as the king who conquered the Mitanni and established the Assyrian Empire as a national entity equal to the other great powers in the region.

REIGN & MILITARY CAMPAIGNS

The kingdom of Mitanni had risen from the land of the Hurrians in eastern Anatolia and was powerful enough to suppress Assyrian hopes of autonomy. When the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (1344-1322 BCE) broke Mitanni’s power, the Assyrians saw an opportunity to launch their own initiatives and tried to take it. They were blocked, however, by Suppiluliuma I’s tactic of placing Hittite rulers on the Mitanni throne and holding the region firmly under Hittite control. The Assyrian king Ashur-UballitI (1353-1318 BCE) defeated the Hittites and expanded the Assyrian kingdom outward from their capital of the city of Ashur, but the next two kings did nothing to capitalize on these successes and the Hittites took back the land. Adad Nirari I succeeded his father, Arik-Den-Ili, who had maintained the Assyrian kingdom but had done nothing to expand or develop it. Adad Nirari I showed himself an ambitious ruler from the beginning of his reign by revitalizing the military and launching campaigns that would lay the foundation for the future grandeur of the Assyrian state. Assyria was not even considered a serious political entity by the other nations in the region before Adad Nirari I, since Ashur had for so long been subject to the rule of the super-power Mitanni and then subject to domination by the Hittites.

ADAD NIRARI I INITIATED WHAT WOULD BECOME STANDARD PROCEDURE FOR THE ASSYRIAN EMPIRE: THE DEPORTATION OF LARGE SEGMENTS OF THE POPULATION.

Adad Nirari I campaigned widely at the head of his army and wanted to make sure that future generations knew of his triumphs. He is the first Assyrian king about whom anything is known with certainty because of his habit of making inscriptions detailing his military victories and accomplishments. His memorial stele reads, in part:

Adad Nirari, illustrious prince, honored of the gods, lord, viceroy of the gods, city-founder, destroyer of the mighty hosts of Kassites, Kuti, Lulumi, Shubari, who destroys all foes north and south, who tramples down their lands from Lubdu and Rapiku to Eluhat, who conquers the whole Kashiaeri region (Luckenbill, 27).

In addition to the peoples and areas he mentions above, he completely conquered the region once held by the Mitanni and brought it securely under Assyrian control by abducting the king, forcing him to swear loyalty, and then releasing him to rule Mitanni as an Assyrian vassal state. He then initiated what would later become standard procedure for the Assyrian Empire: the deportation of large segments of the population. This was not only a punishment inflicted upon a conquered people but a means of adding to the growth and stability of the empire in that those who were re-located were assimilated into pre-existing communities which profited from their labor or area of expertise. If scribes were needed in a certain city then literate people were relocated there while if manual labor was required on building projects in another city, laborers were sent to that location. The relocation of the native population certainly also had the effect of decreasing the likelihood of an uprising, but it seems to have been primarily geared toward the overall improvement of the empire as a whole. Historian Karen Radner comments on this, writing,

The deportees, their labour and their abilities were extremely valuable to the Assyrian state, and their relocation was carefully planned and organised. We must not imagine treks of destitute fugitives who were easy prey for famine and disease: the deportees were meant to travel as comfortably and safely as possible in order to reach their destination in good physical shape. Whenever deportations are depicted in Assyrian imperial art, men, women and children are shown travelling in groups, often riding on vehicles or animals and never in bonds. There is no reason to doubt these depictions as Assyrian narrative art does not otherwise shy away from the graphic display of extreme violence (1).

Following his triumph over Mitanni, Adad Nirari I extended the boundaries of his kingdom south through Babylonia, defeating the Kassite king of Babylon, and demanding tribute from the regions which had been under his control.

Stele of the Assyrian king Adad-Nirari III

THE GREAT KING

Having now conquered the regions that had once dominated Assyria, Adad Nirari I felt he was entitled to the same rights and privileges as the other kings of the region. The great kings of Egypt, of the Hittites, and those formerly of Mitanni, all addressed each other as 'brother' in correspondence and, accordingly, Adad Nirari I saw no reason why he should not now do the same. However, as the historian Trevor Bryce notes,

The mere fact of achieving the status of Great King did not automatically carry with it the right to address one’s peers as `brother’. Nor did securing the right to address one great king as brother automatically confer upon the beneficiary the right to address all Great Kings this way. Urhi-Teshub made this abundantly clear, during his relatively brief occupation of the Hittite throne, to the Assyrian King Adad Nirari I (76).

Mitanni had, of course, been under Hittite control and when Adad Nirari I conquered the region, he wanted to ensure peaceful relations with the Hittites to the north and west. He therefore wrote to the Hittite king Urhi-Teshub (also known as Mursilli III), addressing him as 'brother' and inviting himself to visit the Hittite king so that cordial relations between the two of them could now commence (though it has been suggested that Adad Nirari I was actually threatening Urhi-Teshub and the suggested 'visit' meant a military action). Urhi-Teshub responded, writing,

Why do you continue to speak about brotherhood? For what reason should I write you about brotherhood? Do those who are not on good terms customarily write to one another about brotherhood? On what account should I write to you about brotherhood? Were you and I born from one mother? As my grandfather and my father did not write the King of Assyria about brotherhood, you shall not keep writing to me about brotherhood and Great Kingship. It is not my wish (Bryce, 76-77).

This insult did not seem to bother Adad Nirari I who continued to comport himself as a Great King worthy of the respect of his peers until it became apparent to the other rulers in the region that he was, in fact, one of them and deserved the same honors.

Urhi-Teshub was overthrown by Hattusili III who swiftly made every effort to respect the envoys of the Assyrian king and to write asking him for help in handling a problem with the town of Turira on the upper Euphrates (formerly a Mitanni village, now on the border between the lands of the Hittites and those of the Assyrians) which was harassing the people of the Hittite city of Carchemish. There seems to be no record indicating Adad Nirari I sent any aid to Carchemish and the rest of Hattusilli III’s letter may explain why. The Hittite king apologizes for the way his predecessor treated Adad Nirari I’s envoys and makes mention of their "sad experiences" at the Hittite court. Hattusilli III then rather petulantly complains that Adad Nirari I did not send him gifts at his coronation, which was expected from one great king to another. It could be that Adad Nirari I, now in a secure position of power, no longer felt compelled to seek friendly relations with the kings of the Hittites. He did not need them anymore.

When he had conquered Mitanni, Adad Nirari I took the king Shattuara I back to Ashur in chains, made him swear his allegiance to Assyria, and then released him to rule as an Assyrian vassal. When Shattuara I died, his son Wasashatta mounted a revolt and appealed to the Hittites for aid. The Hittites accepted Wasashatta’s gifts (which would have meant they would grant his request for assistance), but at the time were preoccupied with their relationship with Egypt and, presumably for this reason, never sent the support. It is entirely possible that, recognizing Adad Nirari I’s strength and tallying up his victories in the region, the Hittites simply thought it more prudent not to prompt an Assyrian action against them and to leave Wasashatta to his fate. Adad Nirari I marched his troops into the former Mitanni kingdom, defeated the forces of Wasashatta at the village of Irrite (later known as Ordi), and then continued through the region sacking and plundering the citiesthat had supported the rebellion. He brought the royal family back to Ashur as slaves.

BUILDING PROJECTS & LEGACY

Adad Nirari I ruled for 33 years and, in that time, not only campaigned widely with his army but initiated impressive building projects. After his destruction of the cities in the region of Mitanni, he ordered them re-built on a grander scale. He extended and enlarged the walls of his capital city of Ashur, had larger and longer canals dug, and improved irrigation methods in the region. Temples that had fallen in disrepair or had been damaged by military engagements were restored, and roads were built or improved upon (mainly in order to move his army more quickly through the regions he conquered). By relocating certain segments of the population, he was able to maximize the efficiency of communities in manufacturing necessary commodities, which increased their individual wealth and the wealth of the empire through trade.

After his death, his son Shalmaneser I (1274-1245 BCE) assumed the throne and continued his father’s policies. Shalmaneser I’s son, Tikulti Ninurta I (1244-1208 BCE), would expand on these policies and campaign with his army further than even Adad Nirari I had done. Adad Nirari I’s accomplishments provided these later kings with the resources to further expand the empire and, more importantly, to sustain it through the period which has come to be known as the Bronze Age Collapse (c. 1200 BCE). While other civilizations fell apart, the Assyrian Empire remained relatively intact and, with the rise of the great Tiglath Pileser I (1115-1076 BCE), would continue on to become the greatest empire of the ancient Near East.

Adonis » Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Elias N. Azar

The myth of Adonis, a tale as old as time, is a legendary love story that combines tragedy and death on the one hand, and the joy of coming back to life on the other. The story of the impossibly handsome Adonis and his lover the goddess Aphroditeoriginally dates back to the ancient civilizations of the Near East. It was popular among the Canaanites, and very well-known to the people of Mesopotamia and Egypt as well, though referred to by different names in each civilization. It is the legend of the god of beauty who faced death when he was young, but came back to life for the sake of his beloved Aphrodite. The myth has been a source of great inspiration for many poets, artists and historians alike, leading to its widespread use as a major theme in literary and intellectual productions.

FROM THE CANAANITE ADON TO THE GREEK ADONIS

The god Adon was considered one of the most important Canaanite gods: he was the god of beauty, fertility and permanent renewal. The name itself, “Adon”, means “The Lord” in Canaanite. In Greek mythology and the Hellenic world generally, he was called Adonis, and became known by that name among those nations. Other adaptations of Adon in various civilizations include the Canaanite god Baal who was worshipped in Ugarit, and Tammuz or Dumuzi (meaning July) as he was known to the Babylonians. In Egypt, he was Osiris, the god of resurrection.

In addition to the god Adonis, the myth involves his everlasting mistress Astarte, the goddess of love and beauty. She was known as Aphrodite to the Greeks, and Venus to the Romans. Their stories were so intertwined that Adonis’ myth would be incomplete without mentioning Astarte and the legendary love story that brought them together.

WHEN APHRODITE SAW ADONIS SHE WAS SO AMAZED BY HIS BEAUTY THAT SHE DECIDED TO HIDE HIM FROM THE REST OF THE GODDESSES.

The role that Cyprus played in transferring the myth of Adonis and Astarte from the Canaanite regions to the Greeks – and from the latter to the Romans – is a very significant one. However, perhaps due to the lack of Mesopotamian and Canaanite sources written about this legend (and often the ambiguity of such sources), the late Greek writings are the main references for this tale of eternal love. Hence, the myth is most popularly known as that of Adonis and Aphrodite, rather than Adon and Astarte.

ADONIS IN GREEK MYTHOLOGY

Based on the different Greek sources (such as Bion of Smyrna) and the other Romanreferences (like Ovid's Metamorphoses) a general consensus on the story of Adonis and Aphrodite is as follows:

A great king called Cinyras (in some sources known as Theias, the king of Assyria) had a daughter named Myrrha, who was very beautiful. The king used to boast about his daughter being more beautiful than Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty. When Aphrodite heard of this, she became angry and decided to retaliate. She used her son Eros, the god of desire and attraction, to make Myrrha fall in love with her father, and even deceived him into committing incest. When Cinyras discovered the trick, he swore to kill Myrrha, who in turn escaped from her father after realizing she was pregnant. Myrrha was ashamed and regretful of her heinous act, and pleaded to the gods to protect her. They answered her prayers by turning her into a Myrrh tree.

Nine months later, the Myrrh tree split off, and Adonis was born; he had inherited the beauty of his mother. When Aphrodite saw the boy, she was so amazed by his beauty that she decided to hide him from the rest of the goddesses, and entrusted him to Persephone, goddess of the underworld. Persephone began looking after the boy, and when he grew older and became more and more attractive, she fell in love with him.

A conflict then rose between Aphrodite and Persephone, who refused to give Adonis back to Aphrodite. Zeus, the king of the gods, intervened and ruled that Adonis to spend four months of the year with Persephone in Hades, the Underworld, then four months with Aphrodite, and the remaining four months however he wished. Because Adonis was so taken with the charm of Aphrodite, he devoted his free four months to her as well.

Adonis was well-known for his hunting skills, and in one of the hunting journeys in the Afqa Forest (near Byblos), Adonis was attacked by a wild boar and began bleeding in the hands of Aphrodite, who poured her magical nectar on his wounds. Although Adonis died, the blood blended with the nectar and flowed onto the soil where a flower sprouted from the ground, its scent the same as Aphrodite’s nectar, and its color that of Adonis’ blood – the Anemone flower. The blood reached the river and colored the water red, and the river became known as the "Adonis River" (currently known as Nahr Ibrahim or River Abraham), which is located in the Lebanese village of Afqa.

WORSHIP OF ADONIS

Byblos was one of the main places in the ancient world that used to observe the rituals of Adonis, and actually brought back the practice of these ceremonies and rites well into the early centuries of Christianity. The writings of Lucian of Samosata in the second century CE played a major role in shedding light on the rituals that were widely practiced by the people of Byblos. His book On The Syrian Goddess (De Dea Syria) recounts his visit to the village Afqa, where he explains what he encountered.

According to Lucian, the people of Byblos believed the wild boar incident that befell Adonis happened in their country. To commemorate this event, they would smite themselves each year, mourn, and celebrate religious rituals and orgies while a great mourning prevailed over the entire country. When their beating and bewailing stopped, they would celebrate the funeral of Adonis, as if he had died, and then the next day announce that he had returned to life and was sent to heaven.

Another one of the Byblos region’s marvels is the river that runs from Mount Lebanon and flows into the sea. The River Adonis is said to lose its color every year and take on a bloody red hue, pouring into the sea and dyeing a large part of the beach red – a sign to the people of Byblos to start their time of mourning. It is believed that at this time of year, Adonis was wounded in Lebanon, and his blood went to the riverbed. One of the reasons given by Lucian – as told to him by one of Byblos’ wise men – explaining why the river turns red at this time of the year is the strong wind blowing soil into the river. The soil of Lebanon (and of this region particularly) is known for its red color, which, when mixed with the river water, turns it purple.

THE IMMORTAL MYTH

The popularity of the story of Adonis and his mistress Aphrodite led to a revival of its rituals in many other Phoenician cities as well. It also spread across to the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, but with minor differences in adaptation, depending on the characteristics and features of each civilization. The essence of the legend, however, remains intact across all adaptations: a god of beauty and youth and his relationship with the goddess of love, along with the young god’s death and return to life being a metaphor of nature’s annual rebirth.

The myth of Adonis is closely related to the concept of vegetation and agricultural civilizations, such as Mesopotamia or the Canaanite areas (as the story originated in the Near East). The winter was a season of gloom and sadness for the inhabitants of these areas, whereas the spring and summer brought them the joy of new life. This myth is commonly believed to be an expression of its people's thinking, reflections, and psychological perceptions.

Remnants of Adonis worship are still present in this day and age among some nations of the Levant, Mesopotamia, and even Persia/Iran, where it is manifested as part of spring folklore celebrations, like the Feast of Nauroz.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License