Works and Days » Romanos I » The Early Three Kingdoms Period » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions » Contents

- Works and Days » Origins

- Romanos I » Who was

- The Early Three Kingdoms Period » Origins

Ancient civilizations » Historical places, and their characters

Works and Days » Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Donald L. Wasson

Works and Days is an epic poem written in dactylic hexameter, credited to the 8th-century BCE Greekpoet Hesiod. Hesiod is generally remembered for two epic works, Theogony and Works and Days but, like his contemporary Homer, he was part of an oral tradition and his works were only put into written form decades after his death. Work and Daysis a tribute to the benefits of a life devoted to work and prudence. In the poem, Hesiod speaks directly to his brother Perses on how to conduct his life; a brother who had taken a larger share of their inheritance.

AUTHORSHIP

Very little is known of Hesiod’s life. His father emigrated from Cyme in Asia Minor and settled in Boeotia, a small state in central Greece. His earliest known work Theogony traced the history of creation, Chaos, to the ascension of Zeus as the absolute ruler of the Olympian gods. Although there is some dispute concerning his authorship of Works and Days, classicist Dorothea Wender in her translation of Hesiod believes him to the author of the later and far superior work. While Theogony has historical interest, “… if the reader wants to find the work of a real poet, he should turn to the Works and Days” (19). Centuries later, both poems would have a substantial effect on the Roman poet Ovid and his Metamorphoses.JUSTICE OF ZEUS

Speaking from his own personal experiences, Hesiod praises the benefits of an agrarian life while condemning his brother’s wasted life at sea. Although Wender considers his advice to be both sincere and probably correct, she still referred to Hesiod as “grouchy.” However, while he may seem grouchy, he believed in justice, honesty, piety, self-reliance, and most of all work. He disliked city people, the sea, women, gossip, and laziness. In the opening lines of the poem, he made a plea to Zeus, the Thunderer, to let his brother, who at that time was on a merchant ship, to hear the truth.Primary among Hesiod’s sacred principles was the concept of justice, and to him, Zeus was the utmost representation of justice. According to historian Thomas Martin in his book Ancient Greece, Hesiod viewed justice as a divine quality – embodied in Zeus – that would punish evildoers. However, to Martin, Homer’s Zeus was only concerned with the fate of his beloved warriors in battle; a trait evident in both the Iliad and Odyssey. Historian Norman Cantor in his book Antiquity said that while Homer may be credited with creating the Greek image of the gods and giving them both personality and function, Hesiod demonstrated that they were a moral force, champions of justice. Concerning the power of Zeus, Hesiod wrote:HESIOD BELIEVED IN JUSTICE, HONESTY, PIETY, SELF-RELIANCE, & MOST OF ALL WORK.

With ease he strengthens any man; with easeLater in the poem, Hesiod would lament about the sad times in which he lived, appealing to Zeus “to set our fallen laws upright.” To show the authority of Zeus and teach his brother a lesson, Hesiod turned his attention to Prometheus, considered the craftiest of all. He had stolen fire from the gods and given it to humanity. Having earned a reputation for being vengeful, Zeus wanted to punish the arrogance of man, so he gave them “an evil thing for their delight,” Pandora.

He makes the strong man humble and with ease

He levels mountains and exalts the plain. (59)

Pandora

Pandora first appeared in the Theogony although not by name. She was created in the image of an immortal goddess. Athena taught her to weave. Aphrodite gave her charm and desire. Hermes furnished her with sly manners as well as persuasive words and cunning ways. Adorned by the gods, she was given to Epimetheus (Prometheus’s brother) as his wife. Prometheus had warned him not to accept any gift from Zeus, but he did not listen. Before Pandora, humans had lived free from sorrow, painful work, and disease. However, this gift from the gods became the ruin of humanity, and, according to myth, released countless evils upon the earth, leaving only hope. Hesiod concluded his lesson by saying that there was no way to escape the mind of Zeus, for according to Hesiod, Zeus was all-seeing.THE FIVE RACES

Hesiod next spoke of the five races of humanity. Still speaking to his brother, Hesiod asked to take his tale to heart. The first race was during the time of Cronus, the golden race, and saw humans living with happy hearts without sorrow or work. They never grew old only to die peacefully in their sleep, every want was given to them. At the end of their time on earth, they were to become unseen, living as spirits of the earth.They were replaced by the brief and far inferior silver race, a people who lived anguished lives unable to control themselves, forsaking the gods by leaving the altars bare. Zeus became angry and hid them away to become, in the words of Hesiod, the “spirits of the underworld.” The next race, the aptly named bronze, used bronze weapons and tools, even living in bronze homes.

… and they lovedThey were thought to be invincible only to eventually die by their own hands, nameless, to join Hades, leaving the brightness of the sun. After the bronze, Zeus created a fourth race; a race of godlike heroes. This was the race before Hesiod’s own time; a time of terrible wars and frightful battles. It was the time when Paris stole Helen, initiating the Trojan War. Next came the time of Hesiod – the iron race – a period of hardship and toil.

The groans and violence of war; they ate

no bread; their hearts were flinty-hard; they were

Terrible men. (63)

I wish I were not of this race, that IHe said that during the day people work and grieve but at night they waste away and die. He viewed them as wretched and godless, believing Zeus would eventually destroy them all.

Had died before, or had not yet been born. (64)

ADVICE TO A BROTHER

Hesiod spent the most of the remaining poem giving guidance to his brother. Much of the advice given to Perses centered on the benefits of the agrarian life. He opens the dialogue with a plea:O Perses, think about these things:Hesiod claims that if one is just, Zeus will make him prosperous and not punish him with blight or famine; however, he will admonish those who till the fields of pride. Hesiod further lectures his brother on the evils of idleness, saying that a person who works will be the envy of others, but a greedy person who gains his wealth through lies will be punished by the gods. The best man is one who thinks for himself although he should still listen to another person’s good advice. If he does not think for himself or learn from others, he is a failure as a man.

Follow the just, avoiding violence.

The son of Kronos made this law for men:

That animals and fish and winged birds

Should eat each other for they have no law

But mankind has the law of Right from him,

Which is the better way. (67)

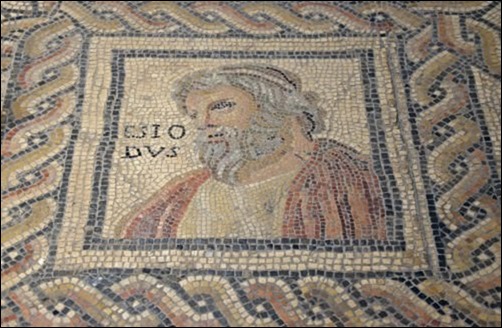

Portrait of Hesiod

In both of his poems, Hesiod does not speak highly of women. In Works and Days, he tells his brother to not be taken in by a woman for she only wants your barn. He warns against women being a cheat and advises his brother to marry when he is ready around the age of thirty. “You must teach her sober ways.” (pg. 81) Repeating his warning from Theogony, he claims that a worthy wife is a prize, but a bad one makes a person shiver in the cold, and a greedy one will bring him “to a raw old age." While he may give his brother advice against marriage, he counsels him to get a house, a woman (a slave), and an ox for plowing, but be sure the woman is unmarried and can help in the field and around the house. Hesiod even describes in detail the plowing of the fields.When ploughing-time arrives, make haste to ploughHesiod warns to be sure to offer a pray to Zeus, the farmer’s god, and Demeter for her sacred grain. He also speaks of the holy days of the month that should be respected for they come from Zeus.

You and your slaves alike, on rainy days

And dry ones, while the season lasts.” (73)

These days are blessings to the men on earth; The rest are fickle, bland, and bring to luck. (86)He advises his brother not to spend time listening to gossip at the blacksmith’s shop for they keep a man from work and consequently helpless and poor in winter.

The idle man who lives on empty hopeWhile he sings the praises of the farm life, he also speaks of the simpler things: owning a fleecy coat, tunic, and ox-hide boots (lined with felt). His advice is not to be too hospitable, yet one should not be seen as unfriendly. One should not be rude at a common feast, and never forget to wash hands before offering wine to the gods. Most wisely, one should never urinate towards the sun or, while traveling, along the side of the road. And, one should never eat from an unblessed pot.

And has no way to earn a living, turns

His mind to crime: hope is not good for him

Who sits and gossips when he has no job. (75)

Fish Plate

Perses is reminded that all work has a season, even sailing. He should admire small ships but put his cargo in a larger one. If he must sail, he should do it after the solstice to avoid the summer heat. Hesiod tells his brother that he, himself, had sailed long ago from Aulis to Euboea. He tells of his experiences with the Muses. It was there that he was taught how to sing.And there, I say, I conquered with a song

And carried home a two-eared tripod, which

I set up for the Muses

in that place

On Helicon, the place where I embarked

On lovely singing, first at their command. (60)

LEGACY

Whether or not Perses gave up his misdirected life and followed his brother’s advice is unknown. Wender believed that while Hesiod may be viewed as conservative and pessimistic, his advice to his brother is sincere and serious. In a comparison of Hesiod to his contemporary Homer, she wrote that Homer’s gods were not very admirable ethically; they lied, cheated, and stole, but they were still quite civilized. Hesiod, on the other hand, let his gods remain primitive and disordered. Norman Cantor believed that both of these Dark Age poets Hesiod and Homer had a profound effect on Greek religion. Cantor wrote that the Greeks had never adopted a code of behavior or any theological beliefs. Their religionwas mostly composed of myths, cults, and rituals. The Greeks accepted the perceptions presented by Homer and Hesiod’s works, creating a unique Greek religion. Hesiod’s poems, while forgotten by many modern readers, had an immense effect on both the Greek people of his time as well as a young poet centuries later, the Roman Ovid.Romanos I » Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

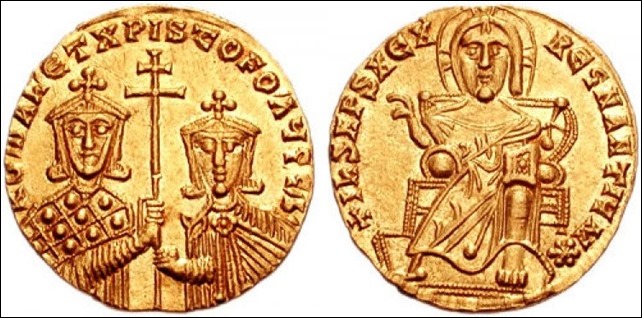

Romanos I Lekapenos (“the Ignorant”) was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 920 to 944 CE. Of Armenian descent, he was a military commander who usurped the throne to rule as co-emperor with the rightful heir, but still minor, Constantine VII (r. 945-959 CE). Achievements made during his reign include peace with Bulgaria, a reconciliation between the conflicting sides of the church over how many marriages an emperor could have, and the instigation of land reforms to prevent the aristocracy gobbling up peasant lands. There were also significant gains made in expanding the empire in Mesopotamia and Armenia, including the acquisition of Melitene and several frontier fortresses.

SUCCESSION

Romanos’ father, Theophylact the Unbearable, was an Armenian peasant who had once helped rescue Basil I (r. 867-886 CE) from the Arabs. In return for this act, Theophylact was given an appointment in the imperial guard. Romanos was born c. 870 CE and, like his father, he enjoyed a career in the Byzantine military and steadily made his way up the ranks on merit to become the strategos or military commander of the Samian province of the empire. He then went on to achieve the lofty position of commander of the imperial fleet in 912 CE. The Armenian, though, harboured even higher ambitions: the throne itself.When Emperor Leo VI died in 912 CE, his chosen heir Constantine VII was still a minor at 6 years of age and so the young ruler’s uncle Alexander seized his opportunity and declared himself emperor. Alexander’s reign would last only one year as his debauched lifestyle finally caught up with him, and he died in the Hippodrome of Constantinople in 913 CE. Two more regents followed: Nicholas I Mystikos, the Patriarch (bishop) of Constantinople and then Zoe, Constantine’s mother. Neither was successful in preventing damaging attacks from the Bulgars and, in 919 CE, Romanos took his chance to become yet another regent for Constantine while Zoe was banished to a nunnery. Romanos would have a few more obstacles yet, though, until he could comfortably seat himself on the Byzantine throne.

Known by the tag Lekapenos, which translates as “an ignorant fellow”, because of his humble origins, Romanos had received the backing of the supporters of the young Constantine because they feared Zoe was planning to marry herself into the powerful but treacherous Phokas family. Once Zoe married the general Leo Phokas it was unlikely that Constantine would ever rule in his own right. Romanos stepped up to the plate promising to protect the emperor’s interests, appointing himself head of the imperial guard in the royal palace. Romanos then cemented his position by marrying his daughter Helena to Constantine in 919 CE.TRIUMPHANT, IN 920 CE ROMANOS AWARDED HIMSELF THE TITLE OF CAESAR & THEN, THREE MONTHS LATER, CO-EMPEROR.

Leo Phokas did not stand idle at this manoeuvre, and he sought to take by force what might have been his through marriage. A rebellion was whipped up, but Romanos responded with a cunning propaganda coup. The admiral, now calling himself basileopater or “father of the emperor”, had a letter spread amongst Leo’s troops which showed in writing Constantine’s support and trust of Romanos. Copies of the letter were circulated in Leo’s camp by a priest and a prostitute, and they convinced the soldiers that Constantine was the legitimate ruler. Leo Phokas’ supporters deserted him, and the general was captured and blinded in the usual horrific Byzantine punishment for those who had tried take power by force.

Triumphant, in 920 CE Romanos awarded himself the title of Caesar and then, three months later, co-emperor. Going a step further, Romanos then crowned his own three sons co-emperors with a higher status than Constantine. It looked very much like Romanos was intent on founding his own dynasty of emperors. To further consolidate his position and that of his family in Byzantine society, the emperor had several of his daughters marry into powerful noble aristocratic clans such as the Argyroi and Musele.

THE TETRAGAMY

One of the first important domestic acts of Romanos’ reign was the reconciliation between the two camps in the Byzantine Church who had argued fiercely over the third and fourth marriages of Leo VI (r. 886-912 CE). Previously, a third marriage by an emperor was regarded as unacceptable, and so when Leo, struggling to find himself a male heir, married for a third time, the crisis known as the tetragamy erupted. The ecclesiastical decree, called the Tome of Union, was passed in 920 CE and, while not posthumously condemning Leo, it did rule that his fourth marriage was illegal. Romanos’ influence on Church policy was further consolidated when he made one of his sons the Patriarch in 925 CE, following the death of Nichols I Mystikos.LAND REFORMS

Romanos was the first of a line of emperors who tried to improve the state treasury and the lot of the peasantry by curbing the growth of the wealthy landed estate owners known as the dynatoi. These landowners had been gobbling up small parcels of peasant holdings, which often meant a reduction in the state’s tax revenue as the landed aristocracy were sometimes exempt from tax duties because of their military or political service. In addition, many peasants, having lost their land, now worked on those estates and so were a tax loss to the state. Accordingly, Romanos passed a law in 922 CE which forbade anyone to buy new land unless they already owned some in that particular village or had some other connection, as the historian T. E. Gregory here explains:[Romanos] devised a system of protimesis (priority) which laid out clearly the order in which peasant land could be purchased. Thus, relatives, joint-holders, and neighbours were given priority, in carefully designated order; only when no one in these categories was able to purchase the land could it be sold to outsiders. Romanos even realised that there would certainly be violation of these principles and he declared that property acquired illegally would have to be returned, without compensation. (257)The measures were not as successful as hoped and another edict was passed in 934 CE which noted that estate owners were, in any case, continuing to acquire new lands and that land must be returned to the peasantry. The problem of large landowners circumventing the law would continue to dog the land reforms of Romanos’ successors, and the real underlying problem of extreme poverty which drove peasants to sell their land or which prevented them from purchasing any remained, too.

DEFENDING THE EMPIRE

The Byzantine Empire had long been struggling with the ambitious Symeon of the Bulgars (r. 893-927 CE), and he moved to attack Constantinople during the chaotic years after Leo VI’s death. Protected by the massive Theodosian Walls, both sides knew that the capital could withstand any siege, and when Symeon’s attempt to enlist the naval help of the Fatamid Caliph in North Africa failed - Romanos had bribed them to remain neutral - the Bulgar leader accepted a generous tribute, the title of Emperor of Bulgaria, and went back home. The wars with the Bulgars finally ended with Symeon’s death in 927 CE, which allowed Romanos to concentrate on offensives elsewhere. To ensure a lasting peace with Bulgaria, Romanos, besides paying another handsome tribute, was prepared to offer Symeon’’s successor, Peter, his own granddaughter, Maria, in marriage.Greek Fire

The gifted general John Kourkouas (aka John Curcuas) was charged with campaigns in Armenia and Mesopotamia to consolidate and expand the Byzantine’s interests there. Inconclusive confrontations finally led to a significant victory and the capture of Melitene in eastern Cappadocia in 934 CE. The Arab general who became Byzantium’s nemesis was Sayf Al-Dawla (aka Saif-ad-Daulah), the Hamdanid emir of Mosul and Aleppo. Despite a Byzantine-Abbasid Caliphate alliance, Sayf inflicted a defeat on Kourkouas in 938 CE on the upper Euphrates and won another important victory near Aleppo in 944 CE. However, in the previous year, Kourkouas had managed to capture the Mesopotamian frontier fortresses of Nisibis, Dara, Amida, and Martyropolis. Finally, in 944 CE, the Byzantine general besieged Edessa in Upper Mesopotamia and forced the city to relinquish the celebrated mandylion, a shroud believed to carry the impression of Jesus Christ. Romanos’ sons proudly paraded the mandylion through the streets of Constantinople, after which it was stored in the royal palace where it remained for the next 250 years.In 941 CE the Rus (descendants of Vikings who had settled around Kiev) launched a failed attack on the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople. Greek Fire, the secret Byzantine weapon of inflammable liquid ensured the Viking ships were easily dealt with at sea, and the arrival of John Kourkouas - recalled from Asia - ensured they were also routed on land.

DEATH & SUCCESSORS

Unfortunately for Romanos’ dynastic plans, his eldest and most able son, Christopher, died in 931 CE and the two remaining sons, not quite so bright, made a poor political move when they invited Constantine to join them in 944 CE to oust their father. Romanos had made signs that given Christopher’s untimely death it was perhaps in the empire’s best interests to have Constantine as full emperor with Romanos’ daughter as his consort maintaining a family connection and perpetuating the Romanos line. When his two sons got wind of the plans to name Constantine as the official heir, they staged a coup against their father in December 944 CE and banished him to a monastery. Fortunately for Constantine, there was significant support at court to return the throne to the legitimate line of descent, and the Romanos boys were kicked out of Constantinople on 27 January 945 CE. Constantine could finally take the throne in his own right, aged 39: it was better late than never. Romanos, still in a monastery in the Princes’ Islands off the coast of Constantinople, died on 15 June 948 CE.This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.

The Early Three Kingdoms Period » Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

The Early Three Kingdoms Period in ancient China, from 184 CE to 190 CE for the purposes of this article, was one of the most turbulent in China’s history. With an ailing Han government unable to control its empire, brutal localised wars, rebellions and uprisings were rife. The capital would soon fall, followed by the Han dynasty itself, split asunder by rival dynastic factions at court, scheming eunuchs, and intractable Confucian literati. The order of the Emperor’s rule was replaced by the chaos of competing warlords, men such as Dong Zhuo, Lu Bu, and Cao Cao, all ruthless and possessing one ambition: to alone rule all of China.Dong Zhuo & Lu Bu

The period has long captured the public imagination beginning in the Sung Dynasty (960-1279 CE) and reaching a fever pitch of interest with The Romance of the Three Kingdoms(Sanguo yanyi), a historical novel written during the Ming Dynasty, either in the 14th or 15th century CE. Attributed by some to Luo Guanzhong, the romanticised and much-embroidered version of events has created lasting cultural heroes and sometimes even figures of worship such as Liu Bei, the Confucianist ruler of the Shu state, and his general Guan Yu, who became the God of War, Guan Di, as well as Sun Quan, the founder of Eastern Wu. The novel covers China’s history from 168 CE to 280 CE and remains wildly popular today, inspiring films, theatre, literature, and computer games.SPONSORSHIP MESSAGE

This article was sponsored by Total War™

Total War: THREE KINGDOMS is the next major historical strategy game in the award-winning Total War series. Forge your legacy. Rewrite history. Shape the future of China.GET THE GAMETHE DECLINE OF THE HAN

The Han dynasty had been ruling China since 206 BCE as its most successful dynasty yet. Still, by the 2nd century CE, the emperors were facing troubled times. The central government, dominated by a secretive Inner Court with access to it strictly controlled by the scheming court eunuchs, was ever-more remote from the affairs of the everyday people in the provinces. Rebellions had already popped up in the 140s CE when they had been dealt with by sending officials to bribe local strongmen. No longer commanding an army of significance, the emperor could do little more.The military forces still under a token allegiance to the Han rulers were permanently stationed on the frontiers, and they had little motivation to remain loyal to their distant commander-in-chief. The Han decision to change the age-old policy of giving only temporary commands of armies for specific campaigns and then recalling generals back to the capital before they got any big ideas would be a fateful one.IT WAS THE INDIVIDUAL COMMANDERS IN THE FIELD WHO EARNED THE RESPECT & LOYALTY OF THEIR TROOPS - A MIX OF PROFESSIONALS, CONVICTS, & LOCAL TRIBESMEN.

It was the individual commanders in the field who earned the respect and loyalty of their troops - a mix of professionals, convicts, and local tribesmen - and not the distant and never-seen emperor. The fact that they received their pay directly from their commander, no doubt, had much to do with this transfer of allegiance. As one local landlord noted:

Orders from the provincial and commandery governments arrive like thunderbolts; imperial edicts are merely hung upon the wall as decoration. (Lewis, 27)Meanwhile, the peasantry at large was suffering from the usual and sadly regular natural disasters that beset China, especially floods and earthquakes, as well as the ongoing war with the people known as the Xianbi. The Xianbi, north of the Great Wall, felt threatened by Chinese expansion and, while they valued Chinese luxury goods through trade and at first welcomed interaction, they came to value their freedom more highly. As Xianbi resistance to Chinese encroachment grew, the Chinese government simply sent more and more military expeditions against them. This policy contributed greatly to undermining imperial authority because so few gains were apparent when compared with considerable losses.

China Warlords, 2nd-3rd century CE.

Little was or could be done to improve the lives of the peasants because the state coffers were emptied by these unsuccessful wars against the Xianbi who, in 177 CE, led the Chinese army into an ambush in the northern steppes which was so successful that “three quarters of the men failed to return” (De Crespigny, 5). Further, the fact that tax was all too often avoided or syphoned off by corrupt officials complicated the lives of the peasantry even more.Regional governors had to find their own way of raising revenue, and there was no guiding policy handed down from the capital. Locals had only one course of action: arm oneself as best as possible for self-defence. Landlords with the means to do so organised their own private armies, recruited from their tenants and local farmers. Those who could not rely on a rich benefactor fled to the hills or elsewhere - resulting in large-scale migrations and attendant instability - and sometimes even whole villages relocated to higher ground where they surrounded themselves with fortifications and hoped for the best. China was very quickly becoming a free-for-all.

THE YELLOW TURBAN REBELLION

In the final two decades of the 2nd century CE, the steady decline of the Han and the now constant rumblings of provincial discontent suddenly burst out of control with one of the most serious and long-lasting rebellions ever witnessed by shocked Chinese rulers and quivering local bureaucrats. The Yellow Turban Rebellion exploded in 184 CE, led by the charismatic Taoist mystic Zhang Jue (died 184 CE), and wreaked havoc on the land.A popular religious movement, the Yellow Turban cult was closely associated with Taoism. Amongst its more appealing principles was the belief that illness came from sin but, especially good news to a peasantry short on medicines, diseases could be removed by confession of those sins. The rebellion was so called because the protagonists wore a turban whose colour represented earth, an element they identified with and which they hoped would put out the fire element associated with their enemy the Han.

Taoist philosophy understood the workings of the universe through the operation of the principle of Yin-Yang and the interaction of the Five Elements: earth, wood, metal, fire, and water. Above the five elements was Tian (heaven) which was represented by the color blue. Taoism was favored by most of the Han emperors and, when the Han first came to power, they associated their dynasty with heaven/blue but at some point changed to earth/yellow and, by the time of the Yellow Turban Rebellion, claimed rule by the power of fire/red. These changes in association with the elements may have to do with the focus of the dynasty at different times but this is unclear.

It is an interesting aspect of the rebellion that, philosophically, the two sides were operating from the same principles of Taoism and the same understanding of what was right and true. The Han claimed justification for rule based on the same principles the rebels were espousing to overthrow them but Zhang Jue and the rebels insisted they were fully justified in that they were identified with the earlier principle of earth/yellow which they claimed the Han had forsaken and betrayed in favor of fire/red.

In this, the rebels were invoking the spiritual concept of jiazhi which had to do with the fundamental value of an individual or action. The jiazhi (literally “worth” or “value”) of the earth - represented by the rebels - was claimed by them as inherently more powerful - and just - than that of their adversaries. By invokingjiazhi in their struggle, the rebels hoped to not only justify their cause but attract more support for the Yellow Turban Rebellion.THE YELLOW TURBAN’S POPULARITY BEGAN IN THE EAST, & IT QUICKLY SPREAD, HELPED BY A TURN TOWARDS POLITICS & THE PROMOTION OF AID TO THE POOR.

The movement’s popularity began in the east, and it quickly spread, helped by a turn towards politics and the promotion of aid to the poor. The movement was vociferous in its criticism of the discrimination against women and the lower classes, which was rife in Chinese society. The cult eventually turned into a major military rebellion, which was rather ironic considering its leader Zhang Jue preached the objective of a Great Peace. The Yellow Turbans were organised into military units and prepared for action. Local government offices were targeted and smashed by the rebels across China. The rebellion seemed to crop up everywhere like cancer - out of control and fatal for the regime. Sixteen commanderies succumbed to the rebels, imperial armies were defeated, rulers kidnapped, and cities captured.

Han Dynasty Sword

The whole of the country was now split into pockets held by rebels, warlords, or regional governors still loyal to the state. The confusion, constant warring, and deprivation of the Chinese people were summarised in a poem attributed to the warlord Cao Cao (c. 155-220 CE), who, like many leaders of the period, had a serious literary bent.My armour has been worn so long that lice breed in it,The rebellion was brutally quashed within a year by an army sent by Cao Cao, then one of the Han emperor Lingdi’s (r. 168-189 CE) foremost generals. Cao Cao had managed to organise a military coalition of the private armies of important nobles at court, and he moulded them into an efficient professional fighting force. The rebel leader Zhang Jue was either killed in battle or executed. The rebellion would, though, rumble on, albeit more quietly, under new leadership in eastern Sichuan province. The damage had been done, though, and now there was very little difference between local governors and local warlords right across China. The Han had dropped the reins of power in the provinces.

Myriad lineages have perished.

White bones exposed in the fields,

For a thousand li not even a cock is heard.

Only one out of a hundred survives,

Thinking of it rends my entrails.

(Lewis, 28)

CAO CAO

Cao Cao had started his career as a commandant and police chief at the Han capital Luoyang during the 170s CE. He early-on established a reputation for being a stickler for the law and was not afraid to challenge the rich and powerful. Cao Cao is portrayed as a deliciously Machiavellian villain in later literature, and Chinese operas, too, cast him as a thoroughly nasty piece of work, with actors portraying the dictator usually wearing a snarling white mask with sinister eyebrows. Indicative of the dubious reputation of the warlord, his name lives on in the Chinese expression “Speak of Cao Cao and he appears” which is broadly equivalent to “Speak of the devil” in English.Cao Cao

There were many other military leaders besides Cao Cao, though, as an unfortunate consequence of the Yellow Turban Rebellion was that several local warlords had been backed by the emperor to raise their own armies and deal with the Yellow Turbans in their particular region. When the rebels were dealt with, these armies then clashed with each other and there followed a sustained period of civil war during which the capital at Luoyang was sacked by one Dong Zhuo (189-192 CE).DONG ZHUO

Dong Zhuo, aka Zhongying, was a frontier general turned warlord based in the northwest of China. He had a long military career, working up the ranks from his starting point as a member of the imperial guards; Zhuo’s unit was the elite corps, the Gentlemen of the Feathered Forest, whose members were composed of sons and grandsons who had lost their fathers in battle. Zhuo was exactly the kind of Han general described above - permanently stationed on the frontiers for a decade and left to his own devices.He was recalled to court in 189 CE but refused on the grounds that his men not only needed him but had forcibly pulled back his carriage and would not let him go. He was fully aware of their loyalties to him alone, as he stated in the following extract from a letter to the court:

My soldiers both great and small have grown familiar with me over a long time, and cherishing my sustaining bounty they will lay down their lives for me. (Lewis, 262)In 189 CE, taking full advantage of the chaos and responding to the call for assistance by the court’s “Grand General” He Jin, half-brother of He, the Empress Dowager, Zhuo moved to within 110 km (70 miles) of Luoyang. At the imperial court, high-ranking officials and military leaders, tired of the ineptitude of government and dominance of the eunuchs, were forced into action when He Jin was murdered in the palace. They thus conspired to assassinate all 2000 of the eunuchs who had been pulling the strings of power for so long.

Chinese Terracotta Warrior

The perpetrators of the coup then made the monumental miscalculation of inviting Zhuo into the city, which then had a population of around 500,000. This the warlord did with relish, burning the capital’s wooden buildings to the ground (including the library and state archives), and kidnapping the young emperor Shaodi. Zhuo was far from his base in the west, though, and so he withdrew, emperor in tow, back to Chang’an. The former Han capital, surrounded by mountains, was a much more easily defendable headquarters. It would take a long time before Luoyang rose again, its sad abandonment noted here a century after Zhuo’s attack by the poet Cao Zhi:Luoyang, how lonesome and still!Dong Zhuo, meanwhile, enjoyed his success. A thorough scoundrel, if later sources are to be believed, Zhuo would go down in history as a mad despot, as this oft-quoted passage from The Romance of the Three Kingdoms reveals:

Palaces and houses all burnt to ashes.

Walls and fences all broken and gaping.

Thorns and brambles rising to the sky.

(Lewis, 101)

On one occasion Dong Zhuo spread a great feast for all those assembled to witness his departure; and while it was in progress, there arrived a large number of rebels from the north who had voluntarily surrendered. The tyrant had them brought before him as he sat at table and meted out to them wanton cruelties. The hands of this one were lopped off, the feet of that; one had his eyes gouged out; another lost his tongue. Some were boiled to death. Shrieks of agony arose to the very heavens, and the courtiers were faint with terror. But the author of the misery ate and drank, chatted and smiled as if nothing was going on. (167)

A BROKEN CHINA

The destruction of Luoyang was another serious blow to the already toppling Han government. Men like Cao Cao and Zhou would continue to battle for control of China and the right to pull the strings of the puppet emperor who remained so necessary for whoever wished to claim a legitimate right to rule. The chaotic Three Kingdoms period witnessed the total break up of China and the country would not be reunified for another three centuries.License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License