Anubis › Aphrodite › A Brief History of Egyptian Art » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Anubis › Who was

- Aphrodite › Who was

- A Brief History of Egyptian Art › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Anubis › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Anubis is the Egyptian god of mummification and the afterlife as well as the patron god of lost souls and the helpless. He is one of the oldest gods of Egypt , who most likely developed from the earlier (and much older) jackal god Wepwawet with whom he is often confused. Anubis' image is seen on royal tombs from the First Dynasty of Egypt (c. 3150-2890 BCE) but it is certain he had already developed a cult following prior to this period in order to be invoked on the tomb 's walls for protection. He is thought to have developed in response to wild dogs and jackals digging up newly buried corpses at some point in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000-3150 BCE) as the Egyptians believed a powerful canine god was the best protection against wild canines.

DEPICTION & ASSOCIATIONS

He is depicted as a black canine, a jackal-dog hybrid with pointed ears, or as a muscular man with the head of a jackal. The color black was chosen for its symbolism, not because Egyptian dogs or jackals were black. Black symbolized the decay of the body as well as the fertile soil of the Nile River Valley which represented regeneration and life. The powerful black canine, then, was the protector of the dead who made sure they received their due rights in burial and stood by them in the afterlife to assist their resurrection. He was known as "First of the Westerners" prior to the rise of Osiris in the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) which meant he was king of the dead (as "westerners" was the Egyptian term for departed souls in the afterlife which lay westward, in the direction of sunset). In this role, he was associated with eternal justice and maintained this association later, even after he was replaced by Osiris who was then given the honorary title 'First of the Westerners'.

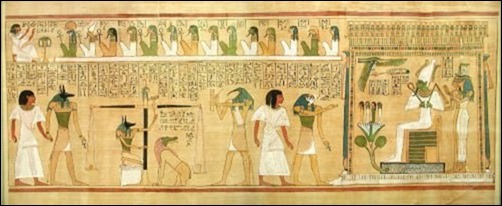

In earlier times, Anubis was considered the son of Ra and Hesat (associated with Hathor ), but after his assimilation into the Osiris myth he was held to be the son of Osiris and his sister-in-law Nephthys . He is the earliest god depicted on tomb walls and invoked for protection of the dead and is usually shown tending to the corpse of the king, presiding over mummification and funerals, or standing with Osiris, Thoth , or other gods at the Weighing of the Heart of the Soul in the Hall of Truth in the afterlife. A popular image of Anubis is the standing or kneeling man with the jackal's head holding the golden scales on which the heart of the soul was weighed against the white feather of truth. His daughter is Qebhet (also known as Kabechet) who brings cool water to the souls of the dead in the Hall of Truth and comforts the newly deceased. Anubis' association with Nephthys (known as "Friend to the Dead") and Qebhet emphasizes his long-standing role as protector of the dead and a guide for the souls in the afterlife.

Book of the Dead

NAME & ROLE IN RELIGION

The name "Anubis" is the Greek form of the Egyptian Anpu (or Inpu ) which meant "to decay" signifying his early association with death. He had many epithets besides "First of the Westerners" and was also known as "Lord of the Sacred Land" (referencing the area of the desert where necropoleis were located), "He Who is Upon his Sacred Mountain" (referencing the cliffs around a given necropolis where wild dogs and jackals would congregate), "Ruler of the Nine Bows" (a reference to the phrase used for traditional enemies of Egypt who were represented as nine captives bowing before the king), "The Dog who Swallows Millions" (simply referring to his role as a god of death), "Master of Secrets" (since he knew what waited beyond death), "He Who is in the Place of Embalming" (indicating his role in the mummification process), and "Foremost of the Divine Booth" referencing his presence in the embalming booth and burial chamber.

As his various epithets make clear, Anubis was central to every aspect of an individual's death experience in the role of protector and even stood with the soul after death as a just judge and guide. Scholar Geraldine Pinch comments on this, writing , "Anubis helped to judge the dead and he and his army of messengers were charged with punishing those who violated tombs or offended the gods" (104). He was especially concerned with controlling the impulses of those who sought to sow disorder or aligned themselves with chaos. Pinch writes:

A story recorded in the first millenium BCE tells how the wicked god Set disguised himself as a leopard to approach the body of Osiris. He was seized by Anubis and branded all over with a hot iron. This, according to Egyptian myth, is how the leopard got its spots. Anubis then flayed Set and wore his bloody skin as a warning to evildoers. By this era, Anubis was said to command an army of demon messengers who inflicted suffering and death. (105)

Anubis, Thoth, & Horus

In the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-2613 BCE) and Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) Anubis was the sole Lord of the Dead and righteous judge of the soul, but as the Osiris myth became more popular, the latter god took on more and more of Anubis' attributes. Anubis remained a very popular god, however, and so was assimilated into the Osiris myth by discarding his earlier parentage and history and making him the son of Osiris and Nephthys born of their affair. According to this story, Nephthys (Set's wife) was attracted by the beauty of Osiris (Set's brother) and transformed herself to appear to him as Isis(Osiris' wife). Osiris slept with Nephthys and she became pregnant with Anubis but abandoned him shortly after his birth in fear that the affair would be discovered by Set. Isis found out about the affair and went searching for the infant and, when she found him, adopted him as her own. Set also found out about the affair, and this is given as part of the reason for his murder of Osiris.

BESIDES HIS EARLY ROLE AS LORD OF THE DEAD, ANUBIS WAS REGULARLY SEEN AS OSIRIS' "RIGHT-HAND MAN" WHO GUARDED THE GOD'S BODY AFTER DEATH, OVERSAW THE MUMMIFICATION, AND ASSISTED OSIRIS IN THE JUDGMENT OF THE SOULS OF THE DEAD.

After his assimilation into the Osiris myth, Anubis was regularly seen as Osiris' protector and "right-hand man" who guarded the god's body after death, oversaw the mummification, and assisted Osiris in the judgment of the souls of the dead. Anubis was regularly called upon (as attested to from amulets, tomb paintings, and in written works) for protection and vengeance;especially as a powerful ally in enforcing curses placed on others or defending one's self from such curses.

Although Anubis is very well represented in artwork throughout Egypt's history he does not play a major role in many myths.His early role as Lord of the Dead, prior to assimilation into the Osiris myth, was static as he only performed a single solemn function which did not lend itself to elaboration. As the protector of the dead, who invented mummification and so the preservation of the body, he seems to have been considered too busy to have involved himself in the kinds of stories told about the other Egyptian gods. Stories about Anubis are all along the lines of the one Geraldine Pinch relates above.

WORSHIP OF THE GOD

The priests of Anubis were male and often wore masks of the god made of wood in performing rituals. The god's cult center was in Upper Egypt at Cynopolis ("the city of the dog"), but there were shrines to him throughout the land and he was universally venerated in every part of the country. Scholar Richard H. Wilkinson writes:

The chapel of Anubis in the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri may have given continuity to an earlier shrine of the god in that area and provides an excellent example of the continuing importance of the god long after his assimilation into the cult of Osiris. Because he was said to have prepared the mummy of Osiris, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers and in the Memphite necropolis an area associated with the embalmers seems to have become something of a focal point for the cult of Anubis in the Late Period and Ptolemaic times and has been termed 'the Anubeion' by modern Egyptologists. Masks of the god are known, and priests representing Anumbis at the preparation of the mummy and the burial rites may have worn these jackal-headed masks in order to impersonate the god; they were certainly utilized for processional use as this is depicted representationally and is mentioned in late texts. The many two- and three-dimensional representations of Anubis which have survived from funerary contexts indicate the god's great importance in this aspect of Egyptian religion and amulets of the god were also common. (190)

Roman Statue of Anubis

Although he does not play a major role in many myths, his popularity was immense, and as with many Egyptian deities, he survived on into other periods through association with the gods of other lands. The Greeks associated him with their god Hermes who guided the dead to the afterlife and, according to Egyptologist Salima Ikram,

[Anubis] became associated with Charon in the Graeco- Roman period and St. Christopher in the early Christian period...It is probable that Anubis is represented as a super-canid, combining the most salient attributes of serveral types of canids, rather than being just a jackal or a dog. (35-36)

This "super-canid" offered people the assurance that their body would be respected at death, that their soul would be protected in the afterlife, and that they would receive fair judgment for their life's work. These are the same assurances sought by people in the present day, and it is easy to understand why Anubis was such a popular and enduring god. His image is still among the most recognizable of all the Egyptian gods, and replicas of his statuary and tomb paintings remain popular, especially among dog owners, in the modern day.

Aphrodite › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Ancient Greek goddess of love, beauty, and desire, Aphrodite ( Roman name: Venus ) could entice both gods and men into illicit affairs with her good looks and whispered sweet nothings.

In mythology the goddess was born when Cronos castrated his father Uranus and cast the genitalia into the sea from where Aphrodite appeared amidst the resulting foam ( aphros ). Believed to have been born close to Cyprus , she was worshipped in Paphos on the island (a geographic location which hints at her eastern origins as a fertility goddess and possible evolution from the Phoenician goddess Astarte).

Compelled by her mother Hera to marry Hephaistos , she was less than faithful, having notorious affairs with Ares , Hermes , and Dionysos . She was the mother of Eros , Harmonia (with Ares), and the Trojan hero Aeneas (with Anchises). The goddess had a large retinue of lesser deities such as Hebe (goddess of youth), the Hours, Dike, Eirene, Themis, the Graces , Aglaia, Euphrosyne, Theleia, Eunomia, Daidia, Eudaimonia, and Himeros.

In mythology Aphrodite is cited as partly responsible for the Trojan War . At the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, Eris (goddess of strife) offered a golden apple for the most beautiful goddess. Hera, Athena , and Aphrodite vied for the honour, and Zeusappointed the Trojan prince Paris as judge. To influence his decision, Athena promised him strength and invincibility, Hera offered the regions of Asia and Europe , and Aphrodite offered the most beautiful woman in the world. Paris chose Aphrodite and so won fair Helen of Sparta . However, as she was already the wife of Menelaos, Paris's abduction of Helen provoked the Spartan king to enlist the assistance of his brother Agamemnon and send an expedition to Troy to take back Helen.

Terracotta Aphrodite, Brundisium

Hesiod describes the goddess as 'quick-glancing', 'foam-born', 'smile-loving', and most often as 'golden Aphrodite'. Similarly, in Homer ’s description of the Trojan War in the Iliad , she is described as 'golden' and 'smiling' and supports the Trojans in the war, in notable episodes, protecting Aeneas from Diomedes and saving the hapless Paris from the wrath of Menelaos.

The birth of Aphrodite from the sea (perhaps most famously depicted on the throne base of the great statue of Zeus at Olympia ) and the judgment of Paris were popular subjects in ancient Greek art. The goddess is often identified with one or more of the following: a mirror, an apple, a myrtle wreath, a sacred bird or dove, a sceptre, and a flower. On occasion, she is also depicted riding a swan or goose. She is usually clothed in Archaic and Classical art and wears an elaborately embroidered band across her chest which held her magic powers of love, desire, and seductive allurement. It is only later (from the 4th century BCE) that she is depicted naked or semi-naked.

A Brief History of Egyptian Art › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Art is an essential aspect of any civilization . Once the basic human needs have been taken care of such as food, shelter, some form of community law, and a religious belief, cultures begin producing artwork, and often all of these developments occur more or less simultaneously. This process began in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE) through images of animals, human beings, and supernatural figures inscribed on rock walls. These early images were crude in comparison to later developments but still express an important value of Egyptian cultural consciousness: balance.

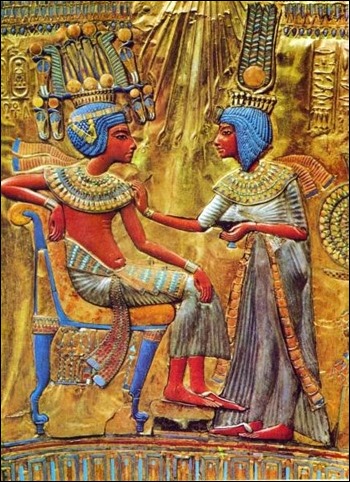

Tutankhamun & Ankhsenamun

Egyptian society was based on the concept of harmony known as ma'at which had come into being at the dawn of creation and sustained the universe. All Egyptian art is based on perfect balance because it reflects the ideal world of the gods. The same way these gods provided all good gifts for humanity, so the artwork was imagined and created to provide a use. Egyptian art was always first and foremost functional. No matter how beautifully a statue may have been crafted, its purpose was to serve as a home for a spirit or a god. An amulet would have been designed to be attractive but aesthetic beauty was not the driving force in its creation, protection was. Tomb paintings, temple tableaus, home and palace gardens all were created so that their form suited an important function and, in many cases, this function was a reminder of the eternal nature of life and the value of personal and communal stability.

EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD ART

The value of balance, expressed as symmetry, infused Egyptian art from the earliest times. The rock art from the Predynastic Period establishes this value which is fully developed and realized in the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE). Art from this period reaches its height in the work known as The Narmer Palette (c. 3200-3000 BCE) which was created to celebrate the unity of Upper and Lower Egypt under King Narmer (c. 3150 BCE). Through a series of engravings on a siltstone slab, shaped as a chevron shield, the story is told of the great king's victory over his enemies and how the gods encouraged and approved his actions. Although some of the images of the palette are difficult to interpret, the story of unification and the celebration of the king is quite clear.

Narmer Palette

On the front, Narmer is associated with the divine strength of the bull (possibly the Apis Bull) and is seen wearing the crown of Upper and Lower Egypt in a triumphal procession. Below him, two men wrestle with entwined beasts which are often interpreted as representing Upper and Lower Egypt (though this view is contested and there seems no justification for it). The reverse side shows the king's victory over his enemies while the gods look on approvingly. All these scenes are carved in low-raised relief with incredible skill.

This technique would be used quite effectively toward the end of the Early Dynastic Period by the architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE) in designing the pyramid complex of King Djoser (c. 2670 BCE). Images of lotus flowers, papyrus plants, and the djed symbol are intricately worked into the architecture of the buildings in both high and low relief. By this time the sculptors had also mastered the art of working in stone to created three-dimensional life-sized statues. The statue of Djoser is among the greatest works of art from this period.

OLD KINGDOM ART

This skill would develop during the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) when a strong central government and economic prosperity combined to allow for monumental works like the Great Pyramid of Giza , the Sphinx , and elaborate tomb and temple paintings. The obelisk, first developed in the Early Dynastic Period, was refined and more widely used during the Old Kingdom. Tomb paintings became increasingly sophisticated but statuary remained static for the most part. A comparison between the statue of Djoser from Saqqara and a small ivory statue of King Khufu (2589-2566 BCE) found at Gizadisplay the same form and technique. Both of these works, even so, are exceptional pieces in execution and detail.

Djoser

Art during the Old Kingdom was state mandated which means the king or a high-ranking nobility commissioned a piece and also dictated its style. This is why there is such uniformity in Old Kingdom artwork: different artists may have had their own vision but they had to create in accordance with their client's wishes. This paradigm changed when the Old Kingdom collapsed and initiated the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE).

ART IN THE FIRST INTERMEDIATE PERIOD

The First Intermediate Period has long been characterized as a time of chaos and darkness and artwork from this era has been used to substantiate such claims. The argument from art rests on an interpretation of First Intermediate Period works as poor quality as well as an absence of monumental building projects to prove that Egyptian culture was in a kind of free fall toward anarchy and dissolution. In reality, the First Intermediate Period of Egypt was a time of tremendous growth and cultural change. The quality of the artwork resulted from a lack of a strong central government and the corresponding absence of state-mandated art.

THE QUALITY OF THE ARTWORK RESULTED FROM A LACK OF A STRONG CENTRAL GOVERNMENT & THE CORRESPONDING ABSENCE OF STATE-MANDATED ART.

The different districts were now free to develop their own vision in the arts and create according to that vision. There is nothing 'low quality' about First Intermediate Period art; it is simply different from Old Kingdom artwork. The lack of monumental building projects during this time is also easily explained: the dynasties of the Old Kingdom had drained the government treasury in creating their own grand monuments and, by the time of the 5th Dynasty, there were no resources left for such projects. The collapse of the Old Kingdom following the 6th Dynasty certainly was a time of confusion, but there is no evidence to suggest the era which followed was any kind of 'dark age'.

The First Intermediate Period produced a number of fine pieces but also saw the rise of mass-produced artwork. Items which had previously been made by a single artist were now assembled and painted by a production crew. Amulets, coffins, ceramics, and shabti dolls were among these crafts . Shabti dolls were important funerary objects which were buried with the deceased and were thought to come to life in the next world and tend to one's responsibilities. These were made of faience , stone, or wood but, in the First Intermediate Period, are mostly of wood and mass produced to be sold cheaply. Shabti dolls were important items because they would allow the soul to relax in the afterlife while the shabti did one's work. Previously, only the wealthy could afford shabti dolls, but in this era, they were available to those of more modest means.

MIDDLE KINGDOM ART

The First Intermediate Period ended when Mentuhotep II (c. 2061-2010 BCE) of Thebes defeated the kings of Herakleopolis and initiated the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE). Thebes now became the capital of Egypt and a strong central government again had the power to dictate artistic taste and creation. The rulers of the Middle Kingdom, however, encouraged the different styles of the districts and did not mandate that all art conform to the tastes of the nobility. Although there was great reverence for Old Kingdom art and, in many cases, an obvious attempt to reflect it, Middle Kingdom Art is distinctive in the themes explored and the sophistication of the technique.

The Middle Kingdom is usually regarded as the high point of Egyptian culture. The tomb of Mentuhotep II is itself a work of art, sculpted from the cliffs near Thebes, which merges seamlessly with the natural landscape to create the effect of a wholly organic work. The paintings, frescoes, and statuary which accompanied the tomb also reflect a high level of sophistication and, as always, symmetry. Jewelry was also refined greatly at this time with some of the finest pieces in Egyptian history dated to this era. A pendant from the reign of Senusret II (c. 1897-1878 BCE) which he gave to his daughter is fashioned of thin goldwires attached to a solid gold backing inlaid with 372 semi-precious stones. The statues and busts of kings and queens are intricately carved with a precision and beauty lacking in much of the Old Kingdom artwork.

Pectoral of Senusret II

The most striking aspect of Middle Kingdom art, however, is the subject matter. Common people, instead of nobility, feature more often in art from this period than any other. The influence of the First Intermediate Period continues to be seen in all the art from the Middle Kingdom, where laborers, farmers, dancers, singers, and domestic life receive almost as much attention as kings, nobles, and the gods. Artwork in tombs continued to reflect the traditional view of the afterlife, but literature from the time questioned the old belief and suggested that one should concentrate on the only life one could be sure of, the present.

This emphasis on life on earth is reflected in less idealistic and more realistic artwork. Kings like Senusret III (c. 1878-1860 BCE) are depicted in statuary and art as they really were instead of as ideal kings. Scholars recognize this by the uniformity and detail of the representations. Senusret III is seen in different works at different ages, sometimes looking careworn, sometimes victorious, whereas kings of earlier eras were always shown at the same age (young) and in the same way (powerful). Egyptian art is famously expressionless because the Egyptians recognized that emotions are fleeting and one would not want one's eternal image to reflect only one moment in life but the totality of one's existence.

Head of Senusret III

Middle Kingdom art adheres to this principle while, at the same time, hinting more at the subject's emotional state than in earlier eras. However the afterlife was viewed at this time, the emphasis in art always gravitates to the here-and-now. Images of the afterlife include people enjoying the simple pleasures of life on earth like eating, drinking, and sowing and harvesting a field. The detail of these scenes emphasizes the pleasures of life on earth, which one should make the most of. Dog collars during this time also become more sophisticated which suggests more leisure time for hunting and greater attention to the ornamentation of simple daily objects.

The Middle Kingdom began to dissolve during the 13th Dynasty when the rulers had grown too comfortable and neglected the affairs of state. The Nubians encroached from the south while a foreign people, the Hyksos , gained a substantial foothold in the Delta region of the north. The government at Thebes lost control of large sections of the Delta to the Hyksos and could do nothing about the growing power of the Nubians; it became increasingly obsolete and ushered in the era known as the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE). During this time the government at Thebes continued to commission artwork but on a smaller scale while the Hyksos either appropriated earlier works for their temples or commissioned for grander works.

SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD/NEW KINGDOM ART

The art of the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt continued the traditions of the Middle Kingdom but often less effectively.The best artists were available to the nobility at Thebes and produced high-quality work, but non-royal artists were less skilled.This era, like the first, is also often characterized as disorganized and chaotic, and the artwork held up as proof, but there were many fine works created during this time; they were simply on a smaller scale.

Tomb paintings, statuary, temple reliefs, pectorals, headdresses, and other jewelry of high quality continued to be produced and the Hyksos, though often vilified by later Egyptian writers, contributed to cultural development. They copied and preserved many of the written works of earlier history which are still extant and also copied statuary and other artworks.

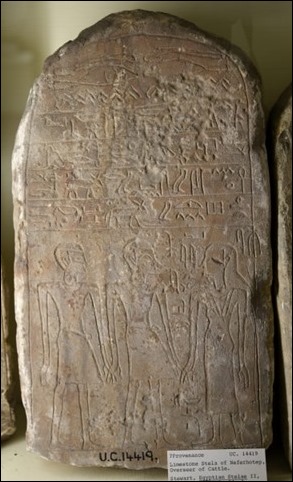

Egyptian Stela of Neferhotep

The Hyksos were finally driven out by the Theban prince Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) whose rule begins the period of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE). The New Kingdom is the most famous era of Egyptian history with the best-known rulers and most recognizable artwork. The colossal statues which were initiated in the Middle Kingdom became more common during this time, the temple of Karnak with its great Hypostyle Hall was expanded regularly, the Egyptian Book of the Dead was copied with accompanying illustrations for more and more people, and funerary objects like shabti dolls were of higher quality.

Egypt of the New Kingdom is the Egypt of empire . As the borders of the country expanded, Egyptian artists were introduced to different styles and techniques which improved their skills. The metalwork of the Hittites which the Egyptians made use of in weaponry also influenced art. The wealth of the country was reflected in the enormity of individual artworks as well as their quality. The pharaoh Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE) built so many monuments and temples that later scholars attributed to him an exceptionally long reign. Among his greatest works are the Colossi of Memnon , two enormous statues of the seated king rising 60 ft (18 m) high and weighing 720 tons each. When they were built they stood at the entrance to Amenhotep III's mortuary temple, which is now gone.

Amenhotep III's son, Amenhotep IV, is better known as Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE), the name he chose after devoting himself to the god Aten and abolishing the ancient religious traditions of the country. During this time (known as the Amarna Period ) art returned to the realism of the Middle Kingdom. From the beginning of the New Kingdom, artistic representations had again moved toward the ideal. During the reign of Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE), although the queen is depicted realistically, most portraits of nobility show the idealism of Old Kingdom sensibilities with heart-shaped faces and smiles. The art of the Amarna period is so realistic that modern-day scholars have been able to reasonably suggest what physical ailments people in the pictures probably suffered from.

Two of the most famous works of Egyptian art come from this time: the bust of Nefertiti and the golden death mask of Tutankhamun . Nefertiti (c. 1370-1336 BCE) was Akhenaten's wife and her bust, discovered at Amarna in 1912 CE by the German archaeologist Borchardt is almost synonymous with Egypt today. Tutankhamun (c.1336-1327 BCE) was Akhenaten's son (but not Nefertiti's) who was in the process of dismantling his father's religious reforms and returning Egypt to traditional beliefs when he died before the age of 20. He is best known for his famous tomb, discovered in 1922 CE, and the vast number of artifacts it contained.

Nefertiti

The golden mask and other metal objects found in the tomb were all the result of innovations in metalwork learned from the Hittites. The art of the Egyptian Empire is among the greatest of the civilization because of the Egyptian's interest in learning new techniques and styles and incorporating them. Prior to the arrival of the Hyksos in Egypt, Egyptians thought of other nations as barbaric and uncivilized and did not consider them worthy of any special attention. The Hyksos 'invasion' forced the people of Egypt to recognize the contributions of others and make use of them.

LATER PERIODS & LEGACY

The skills acquired would continue through the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1069-525 BCE) and Late Period (525-332 BCE), which are also negatively compared with the grander eras of a strong central government. The style of these later periods was affected by the times and the limited resources, but the art is still of considerable quality. Egyptologist David P. Silverman notes how "the art of this era reflects the opposing forces of tradition and change" (222). The Kushite rulers of the Late Period of Ancient Egypt revived Old Kingdom art in an effort to identify themselves with Egypt's oldest traditions while native Egyptian rulers and nobility sought to advance artistic representation from the New Kingdom.

This same paradigm holds with Persian influence following their invasion of 525 BCE. The Persians also had great respect for Egyptian culture and history and identified themselves with Old Kingdom art and architecture. The Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE) blended Egyptian with Greek art to create statuary like that of the god Serapis - himself a combination of Greek and Egyptian gods - and the art of the Roman Egypt (30 BCE - 646 CE) followed this same model. Romans would draw on the older Egyptian themes and techniques in adapting Egyptian gods to Roman understanding. Tomb paintings from this time are distinctly Roman but follow the precepts begun in the Old Kingdom.

Egyptian Oil Lamp with Serapis

The art of these later cultures would come to influence European understanding, technique, and style which would be adhered to for over 1,000 years until artists in the late 19th century CE, such as the Futurists of Italy , began breaking with the past. So-called Modern Art in the early 20th century CE was an attempt to force an audience to see traditional subjects in a new light.Artists like Picasso and Duchamp were interested in forcing people to recognize their preconceptions about art and, by extension, life in creating unexpected and unprecedented compositions which broke from the past in style and technique. Their works and those of others were only possible, however, because of the paradigm created by the ancient Egyptians.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License