Apophis › Apsaras and Gandharvas › Jobs in Ancient Egypt » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Apophis › Who was

- Apsaras and Gandharvas › Who was

- Jobs in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Apophis › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Apophis (also known as Apep) is the Great Serpent, enemy of the sun god Ra, in ancient Egyptian religion . The sun was Ra's great barge which sailed through the sky from dawn to dusk and then descended into the underworld. As it navigated through the darkness of night, it was attacked by Apophis who sought to kill Ra and prevent sunrise. On board the great ship a number of different gods and goddesses are depicted in differing eras as well as the justified dead and all of these helped fend off the serpent.

Ancient Egyptian priests and laypeople would engage in rituals to protect Ra and destroy Apophis and, through these observances, linked the living with the dead and the natural order as established by the gods. Apophis never had a formal cult and was never worshiped, but he would feature in a number of tales dealing with his efforts to destroy the sun god and return order to chaos. Apophis is associated with earthquakes, thunder, darkness, storms, and death, and is sometimes linked to the god Set, also associated with chaos, disorder, storms, and darkness. Set was originally a protector god, however, and appears a number of times as the strongest of the gods on board the sun god's barque, defending the ship against Apophis.

Although there were probably stories about a great enemy-serpent earlier in Egypt 's history, Apophis first appears by name in texts from the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) and is acknowledged as a dangerous force through the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE), especially, and on into the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE) and Roman Egypt . Most of the texts which mention him come from the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE), including the one known as The Book of Overthrowing Apophis which contains the rituals and spells for defeating and destroying the serpent. This work is among the best known of the so-called Execration Texts, works written to accompany rituals denouncing and cursing a person or entity which remained in use throughout ancient Egypt's history.

Ra Travelling Through the Underworld

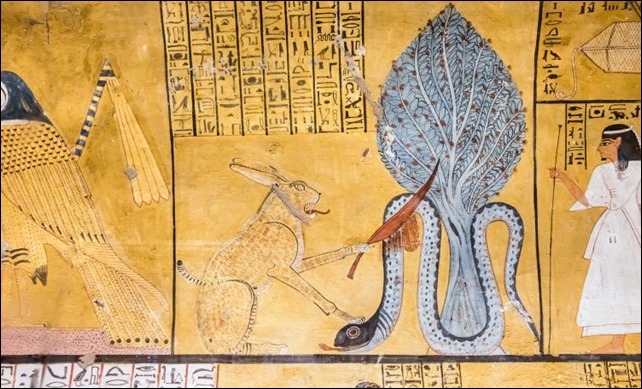

Apophis is sometimes depicted as a coiled serpent but, often, as dismembered, being cut into pieces, or under attack. A famous depiction along these lines comes from Spell 17 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead in which the great cat Mau kills Apophis with a knife. Mau was the divine cat, a personification of the sun god, who guarded the Tree of Life which held the secrets of eternal life and divine knowledge. Mau was present at the act of creation, embodying the protective aspect of Ra, and was considered among his greatest defenders during the New Kingdom of Egypt .

Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson reprints an image in his book The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt from the tomb of Inerkhau at Deir el-Medina in which Mau is seen defending the Tree of Life from Apophis as he slices into the great serpent's head with his blade. The accompanying text, from Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead , relates how the cat defends Ra and also provides the origin of the cat in Egypt; it was divinely created at the beginning of time by the will of the gods.

MYTHOLOGICAL ORIGINS

According to the most popular creation myth, the god Atum stood on the primordial mound, amidst the swirling waters of chaos, and began the work of creation. The god Heka , personification of magic, was with him, and it was through the agency of magic that order rose from chaos and the first sunrise appeared. A variation on this myth has the goddess Neith emerge from the primal waters and, again with Heka, initiate creation. In both versions, which come from the Coffin Texts , Apophis makes his earliest mythological appearance.

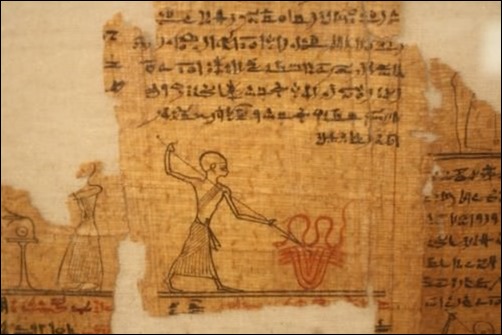

Book of the Dead

In the story concerning Atum, Apophis has always existed and swam in the dark waters of undifferentiated chaos before the ben-ben (the primordial mound) rose from them. Once creation was begun, Apophis was angered because of the introduction of duality and order. Prior to creation, everything was a unified whole, but after, there were opposites such as water and land, light and dark, male and female. Apophis became the enemy of the sun god because the sun was the first sign of the created world and symbolized divine order, light, life, and if he could swallow the sun god, he could return the world to a unity of darkness.

The version in which Neith creates the ordered world is similar but with a significant difference: Apophis is a created being who is given life at the same moment as creation. He is, therefore, not the equal of the earliest gods but their subordinate. In this story, Neith emerges from the chaotic waters of darkness and spits some out as she steps onto the ben-ben . Her saliva becomes the giant serpent who then swims away before it can be caught. When Neith was a part of the waters of darkness, as in the other tale, everything was unified; now, though, there was diversity. Apophis goal was to return the universe to its original, undifferentiated state.

ORDER VS. CHAOS

THE APOPHIS MYTH EPITOMIZES THE MOTIF WHERE THE GODS, THE FORCES OF ORDER, ENLIST THE AID OF HUMANITY TO DEFEND LIGHT AGAINST DARKNESS & LIFE AGAINST DEATH.

One of the most popular literary motifs of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt was order vs. chaos which can be seen in a number of the most famous works. The Admonitions of Ipuwer , for example, contrasts the chaos of the narrator's present with a perfect 'golden age' of the past and the Discourse Between a Man and his Soul does the same on a more personal level. It is not surprising, therefore, to find the Apophis myth emerging during this period because it epitomizes this motif. The gods, the forces of order, enlist the aid of humanity to defend light against darkness and life against death; in essence, to maintain duality and individuality against unity and collectivity.

The personality of an individual was highly valued in Egyptian culture . All the gods were depicted with their own characters and even lesser deities and spirits had their own distinct personalities. The autobiographies inscribed on stelae and tombs was to ensure that the person buried there, that specific individual and their accomplishments, would never be forgotten. Apophis, then, represented everything the Egyptians feared: darkness, oblivion, and the loss of one's identity.

OVERTHROWING APOPHIS

The Egyptians believed that all of nature was imbued with divinity and this, of course, included the sun which gave life.Eclipses and cloudy days were concerning because it was thought the sun god was having problems bringing his ship back up into the sky. The cause of these problems was always Apophis who had somehow gotten the better of the gods on board.During the latter part of the New Kingdom era, the text known as The Book of Overthrowing Apophis was set down from earlier oral traditions in which, according to Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch:

The most terrifying deities in the Egyptian pantheon were evoked to combat the chaos serpent and destroy all the aspects of his being, such as his body, his name, his shadow, and his magic. Priests acted out this unending war by drawing pictures or making models of Apophis. These were cursed and then destroyed by stabbing, trampling, and burning. (108)

Long before the text was written, however, the ritual was enacted. No matter how many times Apophis was defeated and killed, he always rose again to life and attacked the sun god's boat. The most powerful gods and goddesses would defeat the serpent in the course of every night, but during the day, as the sun god sailed slowly across the sky, Apophis regenerated and was ready again by dusk to resume the war. In a text known as the Book of Gates , the goddesses Isis , Neith, and Serket , assisted by other deities, capture Apophis and restrain him in nets held down by monkeys, the sons of Horus , and the great earth god Geb, where he is then chopped into pieces; the next night, though, the serpent is whole again and waiting for the barge of the sun when it enters the underworld.

Mehen

Although the gods were all-powerful, they needed all the help they could get when it came to Apophis. The justified dead who had been admitted to paradise are often seen on the celestial ship helping to defend it. Spell 80 of the Coffin Texts enables the deceased to join in the defense of the sun god and his ship. Set, as noted earlier, is one of the first to drive Apophis off with his spear and club. The serpent god Mehen is also seen on board springing at Apophis to protect Ra. The Egyptian board game mehen , in fact, is thought to have originated from Mehen's role aboard the sun barque. Along with the souls of the dead, however, the living also played a part. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson describes the ritual:

The Egyptians assembled in the temples to make images of the serpent in wax. They spat upon the images, burned them and mutilated them. Cloudy days or storms were signs that Apophis was gaining ground, and solar eclipses were particular times of terror for the Egyptians, as they were interpreted as a sign of Ra's demise. The sun god emerged victorious each time, however, and the people continued their prayers and anthems. (198)

Each morning the sun rose again and moved across the sky and, watching it, the people would know they had played a part in the gods' victory over the forces of darkness and chaos. The first act of the priests in the temples across Egypt was the ritual of Lighting the Fire which re-enacted the first sunrise. This was performed just before dawn in defiance of Apophis' desire to snuff out the light of creation and return all to darkness.

Following Lighting the Fire came the second most important morning ritual, Drawing the Bolt , in which the high priests unlocked and opened the doors to the inner sanctum where the god lived. These two rituals both had to do with Apophis: Lighting the Fire called upon the light of creation to empower Ra and Drawing the Bolt woke the god of the temple from sleep to join in defending the barque of the sun against the great serpent.

CONCLUSION

Rituals surrounding Apophis continued through the Late Period, in which they seem to be taken more seriously than they were previously, and on through the Roman Period. These rituals, in which the people struggled alongside the gods against the forces of darkness, were not particular only to Apophis. The festivals celebrating the resurrection of Osiris included the entire community who participated as two women, playing the parts of Isis and Nephthys , called on Osiris to wake and return to life.At the king's Sed Festival, and others, participants played the parts of the armies of Horus and Set in mock battles re-enacting the victory of Horus (order) over Set (chaos). At Hathor 's festival, people were encouraged to drink to excess in re-enacting the time of disorder and destruction when Ra sent Sekhmet to destroy humanity but then repented. He had a large vat of beer, dyed red, set down in Sekhmet's path at Dendera, and she, thinking it was blood, drank it, became drunk, and passed out.When she woke, she was the gentle Hathor who then restored order and became a friend to humanity.

Set Defeated by Horus

These rituals encouraged the understanding that human beings played an important role in the workings of the universe. The sun was not just an impersonal object in the sky which appeared to rise every morning and set each evening but was imbued with character and purpose: it was the barge of the sun god who, throughout the day, ensured the continuation of life and, at night, required the prayers and support of the people to ensure they would see him the next day. The rituals surrounding the overthrow of Apophis represented the eternal struggle between good and evil, order and chaos, light and darkness, and relied upon the daily attention and efforts of human beings to succeed. Humanity, then, was not just a passive recipient of the gifts of the gods but a vital component in the operation of the universe.

This understanding was maintained, and these rituals observed, until the rise of Christianity in the 4th century CE. At this time, the old model of humanity as co-workers with the gods was replaced by a new one in which human beings were fallen creatures, unworthy of their deity, and utterly dependent upon their god's son and his sacrifice for their salvation. Humans were now considered recipients of a gift they had not earned and did not deserve, and the sun lost its distinct personality and purpose to become another of the Christian god's creations. Apophis, however, would live on in Christian iconography and mythology , merged with other deities such as Set and the benign serpent Sata, as the adversary of God, Satan, who also worked tirelessly to overturn divine order and bring chaos.

Apsaras and Gandharvas › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Anindita Basu

In the Vedas , the apsaras are water nymphs, often married to the gandharvas. By the time the Puranas and the two epics were composed, the apsaras and gandharvas had become performing artists to the gods; the apsaras are singers, dancers, and courtesans, while the gandharvas are musicians. They are somewhat semi-divine; we do not see them as being able to curse humans (except on one occasion) or grant them boons as gods can, but we do see them as adept in magic and knowledgeable in all of the 64 performing arts; additionally, we see many gandharvas skilled in warfare .

IN THE VEDAS

The oldest conception of the apsaras is as river nymphs, and companions to the gandharvas. They are also seen to live on trees, such as the banyan and the sacred fig, and are entreated to bless wedding processions. Apsaras dance, sing, and play around. They are exceedingly beautiful, and because they can cause mental derangement, they are beings who are to be feared. The Rig Veda mentions one apsara by name; she is Urvasi, wife to Pururava, who is an ancestor of the Kauravas and Pandavas . The story is that Urvasi lived with Pururava, a human king, for a while and then left him to return to her apsara and gandharva companions. The distraught Pururava, while wandering around in a forest, spotted Urvasi playing in a river with her friends, and begged her to return to the palace with him. She refused.

किमेता वाचा कृणवा तवाहं प्राक्रमिषमुषसामग्रियेव । पुरूरवः पुनरस्तं परेहि दुरापना वात इवाहमस्मि ॥

...

न वै स्त्रैणानि सख्यानि सन्ति सालावृकाणां हृदयान्येता ॥

I have moved on from you like the first rays of dawn. Go home, Pururava; I am as hard to catch as the wind.

...

Female friendship does not exist; their hearts are the hearts of jackals. [Rig Veda, 10.95]

The gandharvas are companions to the apsaras. They are handsome, possess brilliant weapons, and wear fragrant clothes.They guard the Soma but do not have the right to drink it. How they lost this right has a story: in one version, the gandharvas failed to guard the Soma properly, resulting in it being stolen. Indra brought back the Soma and, as a punishment for their dereliction of duty, the gandharvas were excluded from the Soma draught. In another version, the gandharvas were the original owners of the Soma. They sold it to the gods in exchange for a goddess - the goddess Vach (speech) - because they are very fond of female company.

Apsara

Some scholars trace the origin of the gandharvas to the Indo-Iranian period because the Avesta contains references to a similar being (although in the singular, not plural) called Gandarewa who lives in the sea of white Haoma (Soma).

IN LATER LITERATURE

DUE TO THEIR FRIVOLOUS NATURE AS PERFORMING ARTISTS, APSARAS & GANDHARVAS ARE OFTEN CURSED BY SAGES TO BE BORN ON EARTH AS TREES, ANIMALS, OR DEFORMED BEINGS.

In the epics and the Puranas, the apsaras and gandharvas are artistes who perform at the court of Indra and other gods. They are also seen to sing and dance on other happy occasions such as births and weddings of the gods and also of humans particularly favoured by the gods. Additionally, the apsaras are courtesans to the gods and are frequently employed by Indra to distract kings and sages who Indra fears to be progressing along the path of divinity (and hence capable of depriving Indra of his throne). The Kuru-Pandava teacher Drona was born because his father lost control on seeing an apsara; the famous queen Shakuntala was born of an apsara whom Indra sent to seduce the great sage Vishwamitra (Shakuntala's son Bharat was an ancestor of the Kuru-Pandavas; the country, India , is named after Bharat). An apsara called Tilottama was specially created from the essence of all that is good in all the objects of the universe ( til = particle, uttam = best, tilottama = she of the best of all materials) to distract two demon brothers who were causing major grief to the gods; the brothers fought over her and, in the duel, killed each other.

The gandharvas are musicians par excellence . When Arjuna , the third Pandava, went to the heavens in search of celestial weapons, the gandharvas at Indra's court taught him singing and dancing. The gandharvas are good warriors as well. The Kuru prince and heir apparent, Chitrangad, was killed in a battle by a gandharva of the same name. Another gandharva gave an enchanted war chariot and some divine weapons to Arjuna, and on another occasion, imprisoned Duryodhana and his whole pleasure camp when the two groups entered into a dispute over the rights to a picnic spot.

Gandharva

Perhaps because of their somewhat frivolous nature, both apsaras and gandharvas frequently run afoul of the more staid sages and are cursed by them to be born on earth as trees, animals, or deformed beings, redeemable after thousands of years by the touch or grace of an incarnate god or a human hero.

IN MODERN TIMES

The word apsara is used in Hindi, and other similar languages descended from the Indo-European, to generally denote an exceedingly beautiful woman or a talented dancer.

Jobs in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

In ancient Egypt , the people sustained the government and the government reciprocated. Egypt had no cash economy until the coming of the Persians in 525 BCE. The people worked the land, the government collected the bounty and then distributed it back to the people according to their need and merit. Although there were many more glamorous jobs than farming, farmers were the backbone of the Egyptian economy and sustained everyone else. These farmers knew how to enjoy themselves, greeting the day as another opportunity to make the earth yield food, but looked forward to relaxation time at festivals because they worked so hard, so long, every day; but, in ancient Egypt, so did everyone else.

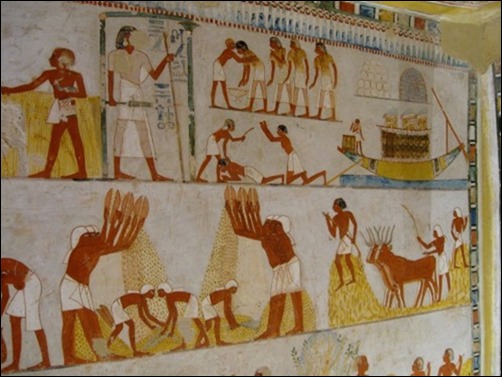

Egyptian Workers

Egypt operated on a barter system up until the Persian invasion of 525 BCE and the economy was based on agriculture. The monetary unit of ancient Egypt was the deben which, according to historian James C. Thompson, "functioned much as the dollar does in North America today to let customers know the price of things, except that there was no deben coin " (Egyptian Economy, 1). A deben was "approximately 90 grams of copper ; very expensive items could also be priced in debens of silveror gold with proportionate changes in value" (ibid). Thompson continues:

Since seventy-five litters of wheat cost one deben and a pair of sandals also cost one deben, it made perfect sense to the Egyptians that a pair of sandals could be purchased with a bag of wheat as easily as with a chunk of copper. Even if the sandal maker had more than enough wheat, she would happily accept it in payment because it could easily be exchanged for something else. The most common items used to make purchases were wheat, barley, and cooking or lamp oil, but in theory almost anything would do. (1)

Laborers were often paid in bread and beer , the staples of the Egyptian diet. If they wanted something else, they needed to be able to offer a skill or some product of value, as Thompson points out. Fortunately for the people, there were many needs which had to be met.

THE SATIRE OF THE TRADES

The commonplace items taken for granted today - a brush, a bowl, a cup - had to be made by hand. In order to have paper to write on, papyrus plants had to be harvested, processed, and distributed, laundry had to be washed by hand, clothing sewn, sandals made, and each of these jobs had their own rewards but also difficulties. Simply doing laundry could mean risking one's life. Laundry was washed by the banks of the Nile River which was home to crocodiles, snakes, and the occasional hippopotamus. The reed cutter, who harvested papyrus plants along the Nile, also had to face these same hazards daily.

These jobs were all held by those at the bottom of the Egyptian social hierarchy and are described in withering detail in a famous literary work from the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE) known as The Satire of the Trades . This piece (also known as The Instructions of Dua-Khety ) is a monologue in which a father, bringing his son to school, describes for the boy all of the difficult and nasty jobs which people have to do every day and compares these to the comfortable and rewarding life of the scribe. Although the piece is obviously satirical in its exaggerated depictions, the description of jobs and their difficulty is accurate.

Satire of the Trades

The father characterizes the life of the carpenter as "miserable" and how the field hand on farms "cries out forever" while the weaver is "wretched" (Simpson, 434). The arrow maker wears himself out trying to gather raw materials and the merchant has to leave home with no guarantee of returning and finding his family intact. The washerman "launders at the riverbank in the vicinity of the crocodile" and his children want nothing to do with him because he is always covered in other people's filth. The fisherman is "more miserable than any other profession" because he must count on his good catch in a day to make a living and must also contend with the dangers in the water which often catch him unawares as "no one told him that a crocodile was standing there" and he is swiftly taken (Simpson, 435). All of these jobs are described in great detail in order to impress on the boy that he should embrace the life of the scribe, the greatest job one could have, as he tells his son:

It is to writings that you must set your mind. See for yourself, it saves one from work. Behold, there is nothing that surpasses writings!...I do not see an office to be compared with it, to which this maxim could relate: I shall make you love books more than your mother and I shall place their excellence before you. It is indeed greater than any office. There is nothing like it on earth. (Simpson, 432-433)

The writer of the Satire , obviously a scribe himself, may have exaggerated somewhat for effect but his argument is basically sound: the occupation of scribe was among the most comfortable in ancient Egypt and certainly compared favorably with most jobs.

UPPER-CLASS JOBS

The jobs of the upper class are fairly well known. The king ruled by delegating responsibility to his vizier who then chose the people beneath him best suited to the job. Bureaucrats, architects, engineers, and artists carried out domestic building projects and the implementation of policies, and the military leaders took care of defense. The priests served the gods, not the people, and cared for the temple and the gods' statues while doctors, dentists, astrologers, and exorcists dealt directly with clients and their needs through their particular (and usually high-priced) skills in magic.

The Seated Scribe

In order to be a member of most of these professions, one had to be literate and so first had to become a scribe. This job required many years of training, apprenticeship, and hard work in memorizing hieroglyphic symbols and practicing calligraphy, but this kind of work would hardly have been thought difficult by many of the lower classes.

As with most if not all civilizations from the beginning of recorded history, the lower classes provided the means for those above them to live comfortable lives, but in Egypt, the nobility took care of those under them by providing jobs and distributing food. One needed to work if one wanted to eat, but there was no shortage of jobs at any time in Egypt's history, and all labor was considered noble and worthy of respect.

LOWER-CLASS JOBS

The details of these jobs are known from medical reports on the treatment of injuries, letters, and documents written on various professions, literary works (such as The Satire on the Trades ), tomb inscriptions, and artistic representations. This evidence presents a comprehensive view of daily work in ancient Egypt, how the jobs were done, and sometimes how people felt about the work.

EVERYONE HAD SOMETHING TO CONTRIBUTE TO THE COMMUNITY, & NO SKILLS SEEM TO HAVE BEEN CONSIDERED NON-ESSENTIAL.

In general, the Egyptians seem to have felt pride in their work no matter their occupation. Everyone had something to contribute to the community, and no skills seem to have been considered non-essential. The potter who produced cups and bowls was as important to the community as the scribe, and the amulet-maker as vital as the pharmacist and, sometimes, as the doctor.

Part of making a living, regardless of one's special skills, was taking part in the king's monumental building projects. Although it is commonly believed that the great monuments and temples of Egypt were achieved through slave labor - specifically that of Hebrew slaves - there is absolutely no evidence to support this claim. The pyramids and other monuments were built by Egyptian laborers who either donated their time as community service or were paid for their labor.

It is also a misconception that slaves in Egypt were routinely beaten and only worked as unskilled laborers. Slaves in ancient Egypt came from many different ethnicities and served their masters in many different capacities according to their skills.Unskilled slaves were used in the mines, as domestic help, and in other menial capacities but were not employed in actually building tombs and monuments like the pyramids.

THE PYRAMID BUILDERS

Egyptians from every occupation could be called on to labor on the king's building projects. Stone had to first be quarried from the mines and this required slaves to split the blocks from the rock cliffs. This was done by inserting wooden wedges in the rock which would swell and cause the stone to break from the face. The often huge blocks were then pushed onto sleds and rolled to a different location where they could be cut and shaped.

The Great Pyramid of Giza is comprised of 2,300,000 blocks of stone and each of these had to be quarried and shaped. This job was done by skilled stonemasons working with copper chisels and wooden mallets. As the chisels would blunt, a specialist in sharpening would take the tool, sharpen it, and bring it back. This would have been constant daily work as the masons could wear down their tools on a single block.

Great Pyramid of Giza

The blocks were then moved into position by unskilled laborers. These people were mostly farmers who could do nothing with their land during the months when the Nile River overflowed its banks. Egyptologists Bob Brier and Hoyt Hobbs explain:

For two months annually, workmen gathered by the tens of thousands from all over the country to transport the blocks a permanent crew had quarried during the rest of the year. Overseers organized the men into teams to transport the stones on sleds, devices better suited than wheeled vehicles to moving weighty objects over shifting sand. (17)

Once the pyramid was complete, the inner chambers needed to be decorated by artists. These were scribes who painted the elaborate images known as the Pyramid Texts , Coffin Texts , and scenes from The Egyptian Book of the Dead . Interior work on tombs and temples also required sculptors who could expertly cut away the stone around certain figures or scenes to leave them in relief. While these artists were highly skilled, everyone - no matter their job the rest of the year - was expected to contribute to communal projects. This practice was in keeping with the value of ma'at (harmony and balance) which was central to Egyptian culture . One was expected to care for others as much as one's self and contributing to the common good was an expression of this.

The jobs people held throughout the year were as varied as occupations are today. When one was not being called upon by community or king to participate in a project, one worked jobs as varied as beer brewer, jewelry maker, sandal maker, basket weaver, armorer, blacksmith, baker, reed cutter, landscaper, wig maker, barber, manicurist, coffin maker, canal digger, painter, carpenter, merchant, chef, entertainer, servant, and many other occupations. The upper class relied heavily upon their servants, and one could make a good living and find advancement in domestic service.

SERVANTS

A servant in a noble or upper-class home might be a slave but usually was a young man or woman of good character who worked diligently. Girls served female mistresses, and boys served male masters. A young person would enter service around the age of 13 and could rise to a prominent position in the household. Personal letters, as well as Letters to the Dead , make clear that a good servant was highly valued and considered vital to the maintenance of the home.

A male servant would serve as his master's messenger and personal butler but could also rise to the position of overseeing other servants in the house and holding considerable authority. Servants could sometimes find themselves working for unpleasant and demanding masters, but they were usually treated well. There is an often-repeated story of Pepi II (2278-2284 BCE) and his aversion to flies: he would smear servants with honey and set them at distances around him to attract the insects. This story is inaccurate, however, as Pepi II actually used slaves as his human insect repellents, not servants. The purposeful mistreatment of a servant would have been considered unacceptable behavior.

Female servants were directly under the supervision of the woman of the house unless she could afford to hire a household manager. This position was usually given to a woman who had proven her worth through years of devoted service. A household manager could live as comfortably as a scribe and enjoyed job security as a valuable member of the home.

Statue of an Ancient Egyptian Servant

The female servants of the wealthy or influential had easier lives than those who served the queen or nobility because the latter had more responsibilities. A servant to the queen had to take particular care of her mistress' wardrobe and wigs, for example, because these would receive more attention than other women's. In the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) the job of a servant of the queen was even more difficult because, when one's mistress died, one went to join her.

Queen Merneith's servants were all sacrificed after her death and buried with her so they could continue their service in the afterlife. This same practice was observed with other rulers, male and female. Future servants were spared this fate with the advent of the shabti doll in the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE). The shabti (also known as ushabti ) served as a replacement for a worker in the afterlife, and so the dolls were buried with the deceased instead of sacrificed servants.

MILITARY SERVICE, ENTERTAINERS, & FARMERS

Women entered domestic service more often than men, who frequently chose to join the army from the Middle Kingdom(2040-1782 CE) onwards. Although one could make a living as a soldier, it was difficult and dangerous work. A significant disadvantage was not only dying on the job but the possibility of being killed somewhere beyond Egypt's borders. Since Egyptians believed that their gods were tied to the land, they feared dying in another country because they would have a harder time making their way to the afterlife. Still, this did not dissuade men from enlisting and, in the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) Egypt had one of the most skilled professional armies in the world.

The armed forces also employed many who were not enlisted to fight. Arms manufacture was always steady work, and after the Hyksos introduced the horse and chariot to Egypt in the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE), tanners and curriers were required to make tack and skilled workers to build chariots.

Men and women could also become entertainers, primarily musicians and dancers. Female dancers were always in high demand as were singers and musicians who would often work for temples providing music at ceremonies, rituals, and festivals. Women were often singers, musicians, and dancers and could command a high price for performances, especially dancers. The dancer Isadora of Artemisia (c. 200 CE) received 36 drachmas a day for performances in Egypt during the Roman Period and for one six-day show was paid 216 drachmas (approximately $5,400). Entertainers performed for the laborers during their building projects, on street corners, in bars, in the market, and, as noted, in temples. Music and dance were highly regarded in ancient Egypt and were considered essential to daily life.

Ancient Egyptian Music and Dancing

At the bottom rung of all these jobs were the people who served as the basis for the entire economy: the farmers. Farmers usually did not own the land they worked. They were given food, implements, and living quarters in return for their labor. The farmer rose before sunrise, worked the fields all day, and returned home toward sunset. Farmers' wives would often keep small gardens to supplement family meals or to trade for other goods.

Many women chose to work out of their homes, making beer, bread, baskets, sandals, jewelry, amulets, or other items for barter. They took on this work in addition to their daily chores which also began before sunrise and continued past nightfall.The Egyptian government was aware of how hard the people worked and so staged a number of festivals throughout the year to show appreciation and give them days off to relax.

As the gods had created the world and everything in it, no job was considered small or insignificant, despite the view of the author of The Satire of the Trades . There is no doubt there were many people who did not love their job every day, but each job was considered an important contribution to the harmony and balance of the land.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License