Artemis › Artemisia I of Caria › The Tales of Prince Setna » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Artemis › Who was

- Artemisia I of Caria › Who was

- The Tales of Prince Setna › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Artemis › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Artemis , daughter of Zeus and Leto, and twin sister of Apollo , was goddess of chastity, hunting, wild animals, forests, childbirth, and fertility. Convincing her father to grant her wishes, Artemis desired to remain forever chaste and unmarried and always to be equipped for hunting. The goddess was also associated with the moon and was the patron of young women, particularly brides-to-be, who dedicated their toys to her as symbolic of the transition to full adulthood and the assumption of a wife's responsibilities.

As a deity of fertility, the goddess was particularly revered at Ephesos , where the famous temple of Artemis (c. 550 BCE) was regarded as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Other notable places of worship were the sanctuaries at Brauron, Tauris, and on the island of Delos , where the goddess was born and where she assisted the birth of her brother Apollo, as Greek mythology tells us.

THE HUNTER AKTAION WAS TURNED INTO A STAG BY THE GODDESS AFTER HE DARED BOAST HE WAS THE GREATER HUNTER.

A notable episode involving the goddess is the saving of Iphigeneia, daughter of Agamemnon . The king had displeased the goddess by killing one of her sacred deer. As punishment, Artemis becalmed the Archaean fleet and only the sacrifice of Iphigeneia would appease the goddess into granting a fair wind to Troy . Agamemnon duly offered his daughter in sacrifice but in pity and at the last moment, the goddess substituted a deer for the girl and made Iphigeneia a priestess at her sanctuary at Tauris.

Other accounts of Artemis, however, display her in a far less charitable light. She is said to have killed the hunter Orion after his attempted rape of either Artemis herself or a follower. Callisto was turned into a bear after she had lain with Zeus, who then turned her and her son Arcas into the constellations the great and little bear. The goddess uses her bow to mercilessly kill the six (or in some accounts seven) daughters of Niobe following her boast that her childbearing capacity was greater than Leto's.The hunter Aktaion was turned into a stag by the goddess after he dared boast he was the greater hunter. Actaion was then torn to pieces by his pack of 50 hunting dogs. Finally, Artemis sent a huge boar to ravage Kalydon after the city had neglected to sacrifice to the goddess. An all-star hunting party of heroes which included Theseus , Jason, the Dioskouroi , Atalanta, and Meleager was organised to hunt and sacrifice the boar in Artemis' honour. After a lengthy expedition, Atalanta and Meleager do finally succeed in killing the boar.

Artemis / Diana

Artemis, playing only a minor role in Homer ’s Iliad , is described most often as 'the archer goddess' but also on occasion as the 'goddess of the loud hunt' and 'of the wild, mistress of wild creatures'. Supporting the Trojans, she notably heals Aeneas after he is wounded by Diomedes. Hesiod in his Theogony most often describes her as 'arrow-shooting Artemis'.

Artemis is most frequently portrayed in ancient Greek art as a maiden huntress with quiver and bow, often accompanied by a deer and on occasion wearing a feline skin. Early representations also emphasise her role as goddess of animals and show her winged with a bird or animal in each hand. For example, on the handles of the celebrated Francois vase , she holds a panther and stag in one depiction and lions in another. In later Attic red- and black-figure vases she is also often depicted holding a torch. A celebrated marble representation of the goddess is on the east frieze of the Parthenon where she is seated with Aphrodite and Eros (c. 440 BCE).

Artemisia I of Caria › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Artemisia of Caria (also known as Artemisia I) was the queen of the Anatolian region of Caria (south of ancient Lydia , in modern-day Turkey ). She is most famous for her role in the naval Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE in which she fought for the Persians and distinguished herself both for her conduct in battle and for the advice she gave the Persian king Xerxes prior to the onset of the engagement. Her name is derived from the Greek goddess Artemis , who presided over the wild and was the patron deity of hunters. She was the daughter of King Lygdamis of Halicarnassus and a Cretan mother whose name is not known. Upon the death of her husband (whose identity is also unknown), Artemisia assumed the throne of Caria as regent for her young son Pisindelis. While it is probable that he ruled Caria after her, there is no record to substantiate this. After the Battle of Salamis, she is said to have escorted Xerxes' illegitimate sons to safety at Ephesos (in modern-day Turkey) and, afterwards, no further mention is made of her in the historical record. The primary source for her achievements in the Greco- Persian wars is Herodotus of Halicarnassus and his account of the Battle of Salamis in his Histories, though she is also mentioned by Pausaniaus, Polyaenus, in the Suda, and by Plutarch .

Every ancient account of Artemisia depicts her as a brave and clever woman who was a valued asset to Xerxes on his expedition to conquer Greece except that of Thessalus who describes her as an unscrupulous pirate and a schemer. It should be noted, however, that later writers on Artemisia I seem to have confused some of her exploits with those of Artemisia II, the wife of King Mausolus of Halicarnassus (died 350 BCE) who, among other achievements, commissioned the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, one the ancient Seven Wonders of the World. The conquest of the city of Latmus as related in Polyaenus (8.53.4), in which Artemisia I stages an elaborate and colorful festival some leagues from the city to draw the inhabitants out and then captures it without a fight, actually was the work of Artemisia II. This same holds true for the suppression of the revolt of Rhodes against Caria in which, after their defeat, the captured fleet of Rhodes sailed back to their home port leading ostensibly seized Carian ships and, in this way, the island was subdued without a lengthy engagement.

ARTEMISIA & THE PERSIAN EXPEDITION

Herodotus praises Artemisia I to such an extent that later writers (many of whom criticized Herodotus on a number of points) complain that he focuses on her to the exclusion of other important details regarding the Battle of Salamis. Herodotus writes:

I pass over all the other officers [of the Persians] because there is no need for me to mention them, except for Artemisia, because I find it particularly remarkable that a woman should have taken part in the expedition against Greece. She took over the tyranny after her husband's death, and although she had a grown-up son and did not have to join the expedition, her manly courage impelled her to do so…Hers was the second most famous squadron in the entire navy, after the one from Sidon . None of Xerxes' allies gave him better advice than her (VII.99).

The Persian expedition was Xerxes' revenge on the Greeks for the Persian defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, and the Persian invading force is reported to have been the largest ever assembled in the world up to that point. Even if Caria, as part of the Persian Empire at the time, had been compelled to supply troops and ships, there would have been no reason for a sitting queen to lead or even accompany her soldiers to the field. Artemisia's decision, then, was wholly her own.

ARTEMISIA FOUGHT IN THE NAVAL BATTLE OF ARTEMISIUM AND DISTINGUISHED HERSELF AS A COMMANDER AND TACTICIAN.

She fought in the naval battle of Artemisium (which took place off the coast of Euboea and concurrently with the land engagement at Thermopylae in late 480 BCE) and distinguished herself as a commander and tactician. It is said she would fly either the Greek or the Persian standard from her ships, depending on circumstance and need, to avoid conflict until she positioned herself favorably for assault or escape. The Battle of Artemisium was a draw but a tactical Persian victory in that the Greek fleet left the field after three days of engagement which allowed the Persian fleet to re-group and strategize. After the defeat of the Greek forces at Thermopylae, the Persian army marched from their base at the Hellespont across the mainland of Greece and razed the city of Athens . The Greeks had abandoned the city before the advance of the Persians and, under the leadership of Themistokles, had rallied their navy off the coast near the straits of Salamis.

ARTEMISIA'S COUNCIL TO XERXES

The Greek mainland had been taken, Athens burned, and Xerxes now called a war council to determine his next move. He could either meet the Greeks in a sea battle in hopes of decisively defeating them or consider other options such as cutting off their supplies and harassing their communities until they sued for peace. Herodotus gives an account of Artemisia's role at the council and the respect she was accorded by Xerxes:

When they had sorted themselves out and were all sitting in their proper places, Xerxes sent Mardonius [his lead general] to test each of them by asking whether or not he should meet the enemy at sea. So Mardonius went around the whole group, starting with the king of Sidon, asking this question. The unanimous view was that he should engage the enemy at sea, with only a single dissenter – Artemisia. She said, “Mardonius, please take this message to the king for me, reminding him that I did not play a negligible or cowardly role in the sea battles of Euboea: Master, it is only right that I should tell you what is, in my honest opinion, the best course of action for you. So here is my advice: do not commit the fleet to battle, because at sea your men will be as inferior to the Greeks as women are to men. In any case, why should you have to run the risk of a sea battle? Have you not captured Athens, which was the point of the campaign? Do you not control the rest of Greece? There is no one to stand against you. Everyone who did so has met with the treatment he deserved. I will tell you what I think the future holds in store for our enemies. If you do not rush into a sea battle, master, but keep your fleet here close to shore, all you need do to gain all your objectives without any effort is either wait here or advance into the Peloponnese . The Greeks do not have the resources to hold out against you for any length of time; you will scatter them and they will retreat to their various towns and cities . You see, I have found out that they do not have provisions on this island of theirs, and if you march overland towards the Peloponnese, it is unlikely that the Greeks from there will remain inactive or will want to fight at sea in defence of Athens. However, if you rush into a sea battle straight away, I am afraid that the defeat of the fleet will cause the land army to come to grief as well.Besides, my lord, you should bear this in mind too, that good men tend to have bad slaves, and vice versa. Now, there is no one better than you, and you do in fact have bad slaves, who are supposed to be your allies – I mean the Egyptians, Cyprians, Cilicians, and Pamphylians, all of whom are useless.”

These words of Artemisia's to Mardonius upset her friends, who assumed that the king would punish her for trying to stop him committing himself to a sea battle, while those who envied and resented her prominence within the alliance were pleased with her reply because they thought she would be put to death. But when everybody's opinions were reported back to Xerxes, he was delighted with Artemisia's point of view; he had rated her highly before, but now she went up even further in his estimation.

Nevertheless, he gave orders that the majority view was the one to follow. He believed that his men had not fought their best off Euboea because he had not been there, and so now he prepared to watch them fight (VIII.67-69).

ARTEMISIA AT SALAMIS

Following the Battle of Artemisium, the Greeks had placed a bounty on Artemisia's head, offering 10,000 drachmas to the man who captured or killed her. Even so, there is no evidence that the queen hesitated to join the sea battle, even though she had advised against it. The Greeks tricked the Persian fleet into the straits of Salamis, feigning a retreat, and then surprised them in attack. The smaller, more agile, ships of the Greeks were able to wreak enormous damage on the larger Persian ships while the latter, owing to their size, were unable to navigate effectively in the narrow confines. Herodotus writes:

I am not in a position to say for certain how particular Persians or Greeks fought, but Artemisia's behavior caused her to rise even higher in the king's estimation. It so happened that in the midst of the general confusion of the Persian fleet, Artemisia's ship was being chased by one from Attica. She found it impossible to escape, because the way ahead was blocked by friendly ships, and hostile ships were particularly close to hers, so she decided on a plan which did in fact do her a lot of good. With the Attic ship close astern, she bore down on and rammed one of the ships from her own side, which was crewed by men from Calynda and had on board Damasithymus, the king of Calynda. Now, I cannot say whether she and Damasithymus had fallen out while they were based at the Hellespont, or whether this action of hers was pre-meditated, or whether the Calyndan ship just happened to be in the way at the time. In any case, she found that by ramming it and sinking it she created for herself a double piece of good fortune. In the first place, when the captain of the Attic ship saw her ramming an enemy vessel, he assumed that Artemisia's ship was either Greek or was a defector from the Persians fighting on his side, so he changed course and turned to attack other ships.

So the first piece of good fortune was that she escaped and remained alive. The second was that, although she was quite the opposite of the king's benefactor, her actions made Xerxes particularly pleased with her. It is reported that, as Xerxes was watching the battle, he noticed her ship ramming the other vessel and one of his entourage said, 'Master, can you see how well Artemisia is fighting? Look, she has sunk an enemy ship!' Xerxes asked if it was really Artemisia and they confirmed that it was because they could recognize the insignia on her ship, and therefore assumed that the ship she had destroyed was one of the enemy's – an assumption that was never refuted, because a particular feature of the general good fortune of Artemisia, as noted, was that no one from the Calyndan ship survived to point the finger at her. In response to what the courtiers were telling him, the story goes on, Xerxes said, “My men have turned into women and my women into men!” (VIII.87-88).

The Battle of Salamis was a great victory for the Greeks and a complete defeat for the Persian forces. Xerxes could not understand what had gone so wrong and was afraid that the Greeks, now emboldened by their victory, would march to the Hellespont, cut down the Persian forces stationed there, and trap him and his forces in Greece. Mardonius suggested a plan whereby he would remain in Greece with 300,000 forces and subdue the Greeks while Xerxes returned home. The king was pleased with this plan but, recognizing that Mardonius had also been among those who supported the disastrous sea battle, called another council to determine the proper plan of action. Herodotus writes, “He convened a meeting of Persians and, while he was listening to their advice, it occurred to him to invite Artemisia along too, to see what she would suggest, because of the earlier occasion on which she had turned out to be the only one with a realistic plan of action. When she came, he dismissed everyone else” (VIII. 101).

Artemisia suggested that he follow Mardonius' plan, saying,

I think you should pull back and leave Mardonius here with the troops he's asking for, since he's offering to do that of his own free will. My thinking is that if he succeeds in the conquests he says he has set himself, and things go as he intends, the achievement is yours, Master, because it was your slaves who did it. But if things go wrong for Mardonius, it will be no great disaster as regards your survival and the prosperity of your house. I mean, if you and your house survive, the Greeks will still have to run many a race for their lives. But if anything happens to Mardonius, if doesn't really matter; besides, if the Greeks win, it won't be an important victory because they will only have destroyed one of your slaves. The whole point of this campaign of yours was to burn Athens to the ground; you've done that, so now you can leave (VIII.101-102).

Xerxes accepted Artemisia's advice this time and withdrew from Greece, leaving Mardonius to fight the rest of the campaign for him. Artemisia was given charge of escorting Xerxes' illegitimate children to safety in Ephesos and, as previously noted, then vanishes from the historical record. Mardonius was killed at the Battle of Plataea the following year (479 BCE) which was another decisive victory for the Greeks and put an end to the Persian invasion of Europe .

THE LEGEND OF HER DEATH

Pausanius claims that there was a marble statue of Artemisia erected in the agora of Sparta , in their Persian Hall, which was created in her honor from the wreckage left behind by the invading Persian forces. The writer Photius (c. 858 CE) records a legend that, after she brought Xerxes' sons to Ephesos, she fell in love with a prince named Dardanus. For unknown reasons, Dardanus rejected her love and Artemisia, in despair, threw herself into the sea and drowned. There is nothing in the reports of the ancient writers which gives any credence to this legend, however. The story is similar to those set down by Parthenius of Nicea (died 14 CE) in his Erotica Pathemata (Sorrows of Romantic Love), a very popular work of tragic love stories, whose purpose seems to have been to serve as a warning on the perils of romantic attachments.

It is possible that Photius, writing much later, chose to draw on the figure of Artemisia to illustrate a similar lesson. While there is nothing in the record to corroborate Photius' version of her death, there is also nothing which contradicts it save the character of the woman as depicted in the ancient histories. Her recent fictional portrayal in the 2014 film 300: Rise of an Empire is in spirit with the ancient sources and hardly supports the claim that such a woman would end her life over the love of a man.

The Tales of Prince Setna › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Among the most engaging and influential works from Egyptian literature are the stories in the cycle known as Setna I and Setna II or The Tales of Prince Setna. These are fictional works from the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE), the Ptolemaic Period (323 -30 BCE), and Roman Egypt (30 BCE-646 CE) featuring Prince Setna Khamwas as the main character in Setna I and as an important secondary character and foil to his son in Setna II. As with any great works of literature , these pieces can be interpreted in many different ways, but their primary purpose was to entertain while teaching important cultural and religious lessons.

The stories have influenced many later writers and important works of literature. Herodotus cites Setna as the high priest Sethos in one of his best-known passages regarding the troops of the Assyrian king Sennacherib defeated by mice who gnaw through their equipment while they sleep (Histories II. 141). This passage is his version of the story told in the biblical book of II Kings 19:35 in which an angel of the Lord destroys the Assyrian army laying siege to Jerusalem . The sequence from Setna II in which Setna and his son Si-Osire travel to the underworld draws upon Greek mythology and influences later Christian scripture in the story of the rich and poor man in the afterlife.

Setna II

In the Setna tale, the rich man suffers in the afterlife for his misdeeds on earth while the poor man is rewarded for maintaining the concept of ma'at (harmony and balance). In the biblical Book of Luke 16:19-31 this same theme is explored through the Rich Man and Lazarus story. Here, a rich man who seems to expect a reward in the afterlife is punished while the poor beggar Lazarus is rewarded in heaven for his suffering on earth.

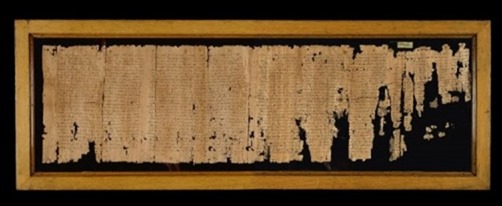

It is hardly surprising that the Setna tales would influence other works as they seem to have been quite popular in their time as copies and fragments of copies exist. The two primary sources of the texts are papyrus scrolls, written in demotic script , presently housed in the Cairo Museum in Egypt (Setna I) and the British Museum in London (Setna II). The beginning of Setna I is damaged but has been reasonably reconstructed using fragments elsewhere and context clues from the intact section of the scroll.

HISTORICAL BASIS FOR THE TALES

The Setna stories are based on the historical figure of Khaemweset (c. 1281 - c. 1225 BCE), the fourth son of Ramesses II(1279-1213 BCE). Khaemweset was High Priest of Ptah and responsible for the upkeep of the temples of Egypt. He went further in his duties than any before or after him, however, in restoring temples and monuments which had fallen into ruin and making sure the original owners' names were inscribed on them. It is due to these efforts that he is remembered as 'the first Egyptologist' in that he studied and preserved the past.

Khaemweset

Khaemweset was well known for entering tombs for preservation work and for his ability to understand ancient inscriptions. By the time the Setna stories were written, he was venerated as a great magician and sage and these aspects of Khaemweset's figure feature prominently in the persona of Prince Setna, whose name is derived from a corruption of Khaemweset's priestly title of Sem or Setem Priest.

Khaemweset's penchant for entering other people's tombs without concern as well as his ability to read Old Kingdominscriptions are developed in Setna I as the main character enters a tomb to retrieve a magical book. Even though Khaemweset was highly regarded, this practice of venturing into tombs was not, and Prince Setna is presented as a man heedless of the consequences of his actions, who impulsively follows his heart instead of the precepts of tradition and cultural values.

SETNA I

The story of Setna I (also known as Setna Khaemuas and the Mummies or Setne Khamwas and Naneferkaptah ) begins with Prince Setna Khamwas, son of Ramesses II, searching for an ancient tomb along with his foster brother Inaros. The tomb is supposed to contain an ancient magic book, but when he enters it, he is confronted by the ghosts of the family: Naneferkaptah, his wife Ahwere, and their son Merib. Ahwere tells Setna he cannot have the book because it is theirs; all three of them died for it.

She then tells him the story of how Naneferkaptah, a great scribe and magician, stole the book, which was handwritten by the god Thoth himself, from a secret hiding place in the sea and Thoth, enraged, drowned first her son, then herself, and Naneferkaptah then drowned himself in grief. Setna does not care and says he will take the book but is then challenged to a game by Naneferkaptah which he loses each time they play. He calls out to Inaros, outside the tomb, to bring him his magic amulets, escapes from the clutches of Naneferkaptah, and steals the book.

SETNA I, BESIDES BEING AN ENTERTAINING ADVENTURE STORY, CONVEYS A NUMBER OF IMPORTANT CULTURAL VALUES SUCH AS NO ONE IS EXEMPT FROM ETERNAL JUSTICE.

Naneferkaptah swears to Ahwere that he will have the book back, and then the scene switches to Memphis where Setna is walking on the street when he sees a beautiful woman and lusts after her. He sends a servant to ask if she will spend an hour with him, but the woman, a daughter of the priest of Bastet named Taboubu, instead invites him to her home in Bubastis.Setna travels there and, in his desire, promises her anything to sleep with her. She has him sign over his home and worldly possessions, then has his children brought so they can witness the transaction legally, and then has the children killed and their bodies thrown into the street for the dogs to eat. Setna, in a trance of lust, is not disturbed by any of this and only wants her more, but when he finally moves to embrace Taboubu, she screams and vanishes. Setna finds himself naked on the street with his penis thrust into a clay pot.

As he is standing there, Pharaoh passes and tells him that everything that transpired was a dream and his children and possessions are all safe and intact. He warns Setna to return the book to Naneferkaptah and make restitution. Setna goes back to the tomb with the book and then travels to Coptos, where Ahwere and Merib are buried, and brings their mummies back to the necropolis of Memphis to be reunited in the tomb with Naneferkaptah. The tomb is then sealed so the book will not be found again and the story ends.

SETNA II

The second Setna tale (also known as Setna and Si-Osire ) opens with Setna's wife, Mehusekhe, praying for a child in the temple . Her prayers are answered, and she gives birth to a son whom the gods have already told Setna should be named Si-Osire. Si-Osire grows quickly, seeming to age in body and in mind much faster than he should. In only a few years he is mature and among the wisest scribes in the land.

One day, his father comments on a funeral procession of a rich man who is followed by many mourners and that of a poor man who has none, stating how the rich man must be so much happier. Si-Osire corrects his father's impression by taking him to the underworld. There they see people who were unfortunate in life, continuing this same trend as they try to plait ropes together, but before they can finish, donkeys chew through their work. There are others they pass who reach for food and water above them, but before they can get to these, others are digging trenches at their feet to prevent them. These people, Si-Osire explains, are those who were grasping in life and so continue to be in death.

They pass by a man crying loudly, crushed in the pivot of a door, and then see a rich man dressed in fine garments standing near Osiris in the hall of judgment. Si-Osire points out that this is the poor man whose funeral they saw earlier, who is now rewarded for his good deeds on earth. The crying man in the doorway is the rich man who engaged in many misdeeds on earth and now must pay for them in the afterlife. Si-Osire explains: "He who is beneficent on earth, to him one is beneficent in the netherworld. And he who is evil, to him one is evil. It is so decreed and will remain so forever" (Lichtheim, 141). Si-Osire then leads his father back to the land of the living.

Detail of Setna II

In the second part of the story, Si-Osire is a grown man when, one day, a Nubian sorcerer comes to the court with a scroll strapped to his body and issues a challenge: if no one in the court can read this scroll without breaking its seal and opening it, he will return to his country and tell everyone there of the shame of Egyptian sages. Pharaoh calls instantly for Setna and asks his advice, but Setna has no idea and asks for ten days in which to deal with the problem. He is granted the time but cannot find the answer to the riddle and becomes depressed.

Si-Osire gets him to talk about his problem and tells him that he can solve it. He shows his power by having his father go downstairs in the house and hold up a book which Si-Osire, obviously, cannot see; but the young man is still able to call out exactly what the book is and its contents. Setna brings the boy to court where he faces the Nubian sorcerer and is able to speak the contents of the scroll. The scroll's story is about Nubian treachery and how a sage named Horus -son-of-the-Nubian-woman battled an Egyptian magician named Horus-son-of-Paneshe. The Egyptian magician prevails, and the Nubian sage is banished from Egypt for 1,500 years. In the end, it is revealed that the Nubian sorcerer is the sage Horus-son-of-the-Nubian-woman from the scroll and Si-Osire is the reincarnation of Horus-son-of-Paneshe who came back to earth just for this purpose: to save Egypt and defeat his ancient enemy.

Si-Osire then destroys the Nubian sorcerer and his mother, who has come to his aid, with magical fire. As the flames consume them, Si-Osire disappears, the flames go out, and the court is as it was before. Setna loudly laments the loss of his son, but the pharaoh consoles him in telling him his son saved Egypt and will always be honored. The story ends with Mehusekhe again praying for a child and becoming pregnant. The couple have another son whom they love, but Setna never forgets Si-Osire and provides his soul with offerings for the rest of his life.

COMMENTARY

Setna I, besides being an entertaining adventure story, conveys a number of important cultural values. Tombs were considered the eternal homes of the dead and tomb robbing was a very serious crime. Execration texts, better known today as 'curses' were often inscribed along with one's autobiography on tomb walls, promising vengeance on any who would desecrate or steal from the deceased. The fact that Setna, identified as a prince, a scribe, and a magician, is punished for this sin would have made it clear that no one is exempt from eternal justice, and those of lesser status could expect even worse treatment.

The story-within-a-story of Naneferkaptah and his family illustrates the danger of stealing from the gods. Naneferkaptah is a proto-Setna in the story, a prince, sage, and magician who disregards cultural values and wisdom to take what he knows he has no right to. He is punished with the deaths of the people he loves most and then loses his life as well. Both men are magicians, and in Setna I and Setna II magic is an important element, just as it was in Egyptian culture ; but Setna I shows how even a skilled magician, learned in his craft, can make a terrible choice in desiring what he has no right to.

Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch has noted that the section of the story about Setna and Taboubu can be interpreted along these same lines but as direct punishment by Bastet for Setna's crime of lust. Setna never sees Taboubu as an individual, as a person, but only as a sex object. Pinch points out how Bastet, as protectress of women, children, and women's secrets, would have been quick to punish a man for treating a woman so poorly. Women were highly regarded throughout Egypt's history and Bastet was among the most popular deities.

Bastet

The author's choice of Taboubu as the daughter of a priest of Bastet invites this interpretation. This section is also thematically linked with the tale of Naneferkaptah and his family in trying to have what is not one's right. Taboubu repeatedly reminds Setna in the story that she is a woman of high birth, associated with the clergy of Bastet, and should be treated with respect; each time Setna only urges her to finish up whatever she needs to do so he can have sex with her.

In the end, all wrongs are righted as Setna repents of his action, returns what does not belong to him, and makes restitution by reuniting the family's mummies in the tomb. Setna II then continues the story with the prince as a married man, whose other children are perhaps grown and have moved on, and how he is rewarded with a savior son.

Setna II is an especially interesting piece in that it contains a number of Greek elements in its depiction of the afterlife and also relies heavily on the concept of reincarnation. Throughout most of Egypt's history, the afterlife was viewed as a continuation of one's journey on earth. Once one died, one stood in judgment before the divine tribunal and then, hopefully, was justified and went on to an eternal paradise which perfectly mirrored one's time on earth. In certain periods, such as the Middle Kingdom of Egypt , this view was questioned but it remained fairly constant and even in that era was still accepted.

There was another view, however, concurrent with this one, which emphasized the cyclical nature of life and supported the concept of the Transmigration of Souls, better known today as reincarnation. Once the soul was justified by Osiris after death, it could go on to paradise or return to earth to be reborn in another body. Si-Osire, although certainly Setna's son, is also the reincarnation of the sage Horus-son-of-Paneshe who is allowed to return to earth for a very specific reason: to save Egypt and Egypt's king from the treachery of the Nubian sorcerer. This option seems to have only been open to souls who had been justified by earlier good deeds on earth and, through them, the maintenance of harmony and balance.

Contrasted with the justified soul of Horus-son-of-Paneshe are the dead seen in the underworld. Those who had never succeeded in life and blamed everyone except themselves for failure were sentenced to endless futility as they try to plait ropes which are then eaten by donkeys. People who were never satisfied and always grasping continued to do so eternally as they struggle to get to the food and water they will never reach. This symbolism, as scholar Miriam Lichtheim points out, is distinctly Greek and reminiscent of the story of Tantalus , of Sisyphus , and of the Danaids.

The contrast of the rich and poor man in life and death, later skillfully used by the author of the Book of Luke, illustrates the importance of the central value of ancient Egypt: observance of ma'at . There was nothing wrong, per se , in having riches.Pharaoh, after all, was quite wealthy and yet no one doubted the king would find himself justified in the afterlife and continue on to the Field of Reeds. The autobiographies and tomb inscriptions of plenty of wealthy ancient Egyptians, from different eras, express the same confidence.

What should be noted in this section of the story is what brings the two men to their respective fates: the poor man did "good works" while the rich man's misdeeds were greater than his good ones. This would have been understood as the difference between keeping ma'at as one's focus in life or putting one's self first before the good of others. The rich man would not have been punished for his wealth but for his selfishness and lack of concern for ma'at . In Setna I, the prince learns his lesson about taking what does not belong to him; in the second Setna, one sees in the rich man's fate what happens to those who do not learn that lesson.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License