Achievements of the Han Dynasty › Amun › Anaximander » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Achievements of the Han Dynasty › Origins

- Amun › Who was

- Anaximander › Who was

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Achievements of the Han Dynasty › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

The achievements of the Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE), often regarded by scholars and the ancient Chinese themselves as the golden era of Chinese culture, would have lasting effects on all who followed, particularly in the areas of government, law, philosophy, history, and art. The thirst for new knowledge, ambitious experimentation, and unstinting intellectual enquiry are hallmarks of Han culture, and they helped, amongst other achievements, to develop the Silk Road trade network, invent new materials such as paper and glazed pottery, formulate history writing, and greatly improve agricultural tools, techniques, and yields.

Han Women, Dahuting Tomb.

THE SILK ROAD

The Han Dynasty saw the first official trade with western cultures from around 130 BCE. Many types of goods from foodstuffs to manufactured luxuries were traded, and none were more typical of ancient China than silk. As a result of this commodity, the trade routes became known as the Silk Road or Sichou Zhi Lu. The 'road' was actually an entire network of overland camel caravan routes connecting China to the Middle East and hence is now often referred to as the Silk Routes by historians.Goods were imported and exported via middlemen as no single trader ever travelled the length of the routes. Eventually, the network would spread not only to neighbouring states such as the Korean kingdoms and Japan but also to the great empires of India, Persia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Besides physical goods, one of the major consequences of the Silk Road was the exchange of ideas between cultures carried not only by traders but also diplomats, scholars, and monks who travelled the routes across Asia. Languages (especially the written word), religions (notably Buddhism ), foodstuffs, technology, and artistic ideas were spread so that cultures across Asia and Europe helped each other to develop.

A HALLMARK OF THE THINKING OF THE PERIOD IS ONE OF OPEN ENQUIRY INTO ANY IDEOLOGY WHICH COULD ADEQUATELY EXPLAIN HUMANITY'S POSITION IN THE COSMOS.

PHILOSOPHY & EDUCATION

Confucianism was officially adopted as the state ideology of the Han dynasty but, in practice, principles of Legalism were followed too, which created a philosophical blend aimed at ensuring the welfare of all based on strong legal principles. Taoismwas another influential philosophy in politics and a hallmark of the thinking of the period is one of open enquiry into any ideology which could adequately explain humanity's position in the cosmos and forge a link between government, religion, and cosmology. Theories involving numbers were particularly popular with intellectuals who searched for an all-embracing ideology to explain all facets of the human condition.

One tangible consequence of the promotion of Confucianism and other philosophies by the state was the building of schools and colleges to promote literacy so that the classic texts of Chinese thought might be studied. An Imperial Academy was established in 124 BCE for scholars to study in depth the Confucian and Taoist Classics. By the end of the Han period, the Academy was training an impressive 30,000 students each year. In general, the state held the view that education was a mark of a civilised society, although the expense of sending young people to school severely limited access to education in practice.Society remained highly stratified but, at least for those who had the means to an education, there was now the possibility of access to the state bureaucracy.

East Asia in the year 1 CE

In addition to the promotion of philosophy, the destruction of many books on all manner of topics by the Qin emperor Shi Huangti (259-210 BCE) necessitated a massive rewriting project to preserve from memory the accumulated knowledge within those lost works. Inevitably perhaps, while reformulating the past, Han writers were selective according to their own ideas and those of their patrons but, so too, they very often put on record contemporary thought so that the Han dynasty is one of the best-documented periods of Chinese history.

LITERATURE

The earliest surviving literature from ancient China dates to the Han period, although the possibility that earlier writings were deliberately destroyed or have simply been lost over time is not to be discounted. The most famous Han work is undoubtedly the Shiji ( Historical Records or Records of the Grand Historian ) by Sima Qian (135 - 86 BCE) who is often cited as China's first historian. Qian was actually the court's Grand Astrologer, but as this also meant he had to compile records of past omens and create guides for future imperial decisions, he was, in effect, a historian. The Shiji draws on both oral and written records, including those in the imperial archives, and was begun by Qian's father Sima Tan. The Shiji goes much further than recording astrological phenomena and documents the imperial dynasties in sequence, beginning with early legendary emperors and ending in Qian's own time. Thus, the 130 chapters cover two and a half millennia of history. With a new systematic approach and including descriptions of technological and cultural developments as well as biographies of non-royal famous figures and foreign peoples, the work would hugely influence the official Chinese histories that followed in subsequent dynasties.

Sima Qian

Another important Han work and another first is the Canon of Medicine credited to the Yellow Emperor, which is a record of medicine in Han China. The writer Ban Gu (32-92 CE), besides writing his famous history Hanshu ( History of the Western Han Dynasty ), created a new genre, rhapsody or fu, most famously seen in his Rhapsody on the Two Capitals. Involving dynamic dialogues between two characters, his works are valuable records of local customs and events. By the 1st century CE, the surge in Han literature meant that the imperial library boasted some 600 titles which included works of philosophy, military treatises, calendars, and works of science.

ART

The stability provided by the Han government and consequent accumulation of wealth by its more fortunate citizens resulted in a flourishing of the arts. Wealthy individuals became both patrons and consumers of fine art works. This demand led to innovations and experimentation in art, notably the first glazed pottery and figure painting. The latter was the first Chinese attempts at realistic portraiture of ordinary people. Capturing natural landscapes became another preoccupation of Han artists.Art was previously concerned with religion and ceremonies but now came to focus on people and everyday life activities such as hunting and farming. Tomb paintings, especially, sought to pick out the individual facial characteristics of people and depict narrative scenes.

THE COMBINATION OF BRUSH, INK & PAPER WOULD ESTABLISH PAINTING & CALLIGRAPHY AS THE MOST IMPORTANT AREAS OF ART IN CHINA.

PAPER

One invention which greatly helped the spread of literature and literacy was the invention of refined paper in 105 CE. The discovery, using pressed plant fibres which were then dried in sheets, was credited to one Cai Lun, the director of the Imperial Workshops at Luoyang. Heavy bamboo or wooden strips and expensive silk had long been used as a surface for writing but, after centuries of endeavour, a lighter and cheaper alternative had finally been found in the form of paper scrolls. The combination of brush, ink, and paper would establish painting and calligraphy as the most important areas of art in China for the next two millennia. One other Han innovation was to use paper to produce topographical and military maps. Drawn to a reasonably accurate scale they included colour-coding, symbols for local features, and specific areas of enlarged scale.

SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

The Han period witnessed a number of important technical inventions and improvements which helped make agriculture much more efficient than in previous times. Better metalworking skills and the wider use of iron meant tools were more effective. The plough, in particular, was greatly improved, and now had two blades instead of one. It was more easily directed, too, with the addition of two handles. The arrival of the wheelbarrow helped farmers shift loads more efficiently. Fans were used to separate kernels from the chaff, and hand mills ground up the flour. Irrigation was greatly improved by mechanised pumps - worked either by a pedal or using a pole with a counterweighted bucket - and wells were made more efficient reservoirs by lining them with bricks. Meanwhile, crop management became more sophisticated with greater care taken over the timing of planting and the sowing of alternate crops in successive rows to maximise yields.

Han Dynasty Farm Model

Another area which benefitted from Han investment was the construction of a more extensive road and waterways network, as well as better built harbours. Weaving greatly improved under the Han, especially of silk which, using new foot-powered looms, could have as many as 220 warp threads per centimetre of cloth. Innovations were also made in science such as the use of sundials and primitive seismographs. In medicine, one popular development was the use of acupuncture.

IN WARFARE, THE CROSSBOW & CAVALRY BECAME MUCH MORE WIDELY USED.

In warfare, the crossbow became much more widely used and now came in more sizes from heavy mounted artillery to light handheld versions. The Han made a far greater use of cavalry than their predecessors, too, making the battlefield a more dynamic and deadly arena. Han swords, halberds, and armour were noted for their craftsmanship and benefitted from the use of iron and low-grade steel.

SOCIAL CHANGES

Although not necessarily 'achievements', the Han government did pass laws which resulted in several significant changes in the ordinary lives of its citizens. Universal conscription had been a feature of an unsettled China for centuries but, in 31 CE, the Han abolished it. Finally recognising that forcing farmers to fight was not the best way to achieve a disciplined and skilled fighting force, they instead (more or less) created a professional army. The sheer size of the Han empire necessitated a huge number of soldiers to defend the borders, but these were now recruited from available mercenaries, conquered tribes, and released prisoners instead of full-time farmers. In addition, the Han government invested some 10% of its revenue on extravagant gifts to rival states. Many states sent tribute in return, and the establishment of strong diplomatic relations ensured that less investment was needed in military defence.

One of the notable changes in the family's dealings with the state was the government's decision to nominate and deal with only one representative of each family unit. Typically, this role went to the most senior male but it could be temporarily held by a woman if her sons were not yet of age. Family ties were strengthened by making everyone responsible for the conduct of each other member in the unit. If one family member was convicted of a serious crime, for example, then the other family members could be enslaved as a wider punishment. Another change was inheritance. Whereas previously the senior male inherited everything, the Han changed the rules to equally distribute inheritance among all male siblings. Daughters still got nothing, though, and their only hope for some financial independence was the dowry their family might provide for them.

An unfortunate consequence of the changes in inheritance was that, over time, farms became smaller and smaller as they were parcelled out to brothers, and it became more difficult to support a family on a single plot. This, in turn, led to small farmers selling out and preferring to work for larger landed estate owners, eventually concentrating land ownership in fewer and fewer hands. Ultimately, the combination of the loss of tax revenue this caused, the general disaffection of the peasantry, and the increase in wealth and power of the aristocracy would lead to the overthrow of the Han dynasty and the splitting of China into three warring kingdoms.

Amun › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

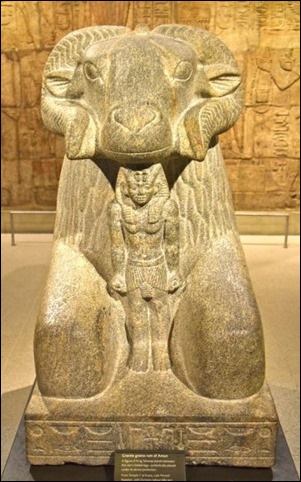

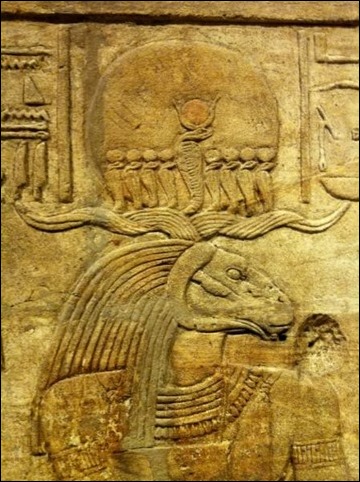

Amun (also Amon, Ammon, Amen) is the ancient Egyptian god of the sun and air. He is one of the most important gods of ancient Egypt who rose to prominence at Thebes at the beginning of the period of the New Kingdom (c.1570-1069 BCE). He is usually depicted as a bearded man wearing a headdress with a double plume or, after the New Kingdom, as a ram-headed man or simply a ram, symbolizing fertility in his role as Amun-Min. His name means "the hidden one," "invisible," "mysterious of form," and unlike most other Egyptian gods, he was considered Lord of All who encompassed every aspect of creation.

ORIGIN & RISE TO PROMINENCE

Amun is first mentioned in the Pyramid Texts (c. 2400-2300) as a local god of Thebes along with his consort Amaunet. At this time, the supreme god of Thebes was the war god Montu and the creator god was regarded as Atum (also known as Ra).Montu was a fierce warrior who protected the city and helped it expand while Atum was the supremely powerful, self-created deity who arose on the primordial mound from the waters of chaos at the beginning of creation. Amun, at this time, was associated with protecting the king but, largely, was simply a local fertility god paired with his consort Amaunet as part of the Ogdoad, eight gods who represented the primordial elements of creation.

Amun was considered no more powerful or significant than the other gods who were part of the Ogdoad but represented the element of "hiddenness" or "obscurity" while the others represented more clearly defined concepts such as "darkness," "water," and "infinity." Amun as "The Obscure One" left room for people to define him according to their own understanding of what they needed him to be. A god who represented darkness could not also represent light, nor a god of water stand for dryness, etc. A god who personified the mysterious hidden nature of existence, however, could lend himself to any aspect of that existence; and this is precisely what happened with Amun.

Amun, Mut, and Khonsu

Around c. 1800 BCE the Hyksos, a mysterious people most likely from the Levant, settled in Egypt, and by c. 1720 BCE they had grown powerful enough to take control of Lower Egypt and render the court at Thebes obsolete. This era is known as The Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-c.1570 BCE) in which the Hyksos ruled Egypt. In c. 1570 the prince Ahmose I (c. 1550-c.1525 BCE) drove the Hyksos out of the country and re-established the city of Thebes.

Since the time of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) Amun had been growing in power in Thebes and was a part of the Theban triad of deities with his consort Mut (who replaced Amaunet) and their son Khonsu, the moon god. When Ahmose Idefeated the Hyksos he attributed his victory to Amun linking him to the well-known sun god Ra. As Amun was "The Hidden One" linked to no definable natural phenomenon or principle, he was malleable enough to fit with any attribute one wished to add to him. In this case, the mysterious aspect of life - that which makes life what it is - was linked to the visible life-giving aspect of existence: the sun. Amun then became Amun-Ra, creator of the universe, and King of the Gods.

KING OF THE GODS

Following Amun's ascendancy during the New Kingdom, he was hailed as "The Self-created One" and "King of the Gods" who had created all things, including himself. He was associated with the sun god Ra who was associated with the earlier god Atum of Heliopolis. Although Amun took on many of Atum's attributes and more or less replaced him, the two remained distinct deities and Atum continued to be venerated. In his role as Amun-Ra, the god combines his invisible aspect (symbolized by the wind which one cannot see but is aware of) and his visible aspect as the life-giving sun. In Amun, the most important aspects of both Ra and Atum were combined to establish an all-encompassing deity whose aspects were literally every facet of creation.

IN AMUN, THE MOST IMPORTANT ASPECTS OF BOTH RA & ATUM WERE COMBINED TO ESTABLISH AN ALL-ENCOMPASSING DEITY WHOSE ASPECTS WERE LITERALLY EVERY FACET OF CREATION.

His cult was so popular that, as scholar Richard H. Wilkinson observes, Egyptian religion became almost monotheistic and Amun "came particularly close to being a kind of monotheistic deity" (94). The popularity of this god, in fact, ushered in the first monotheistic religious movement in Egypt under Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE) who banned polytheistic worship and established the state religion of the one true god Aten.

Although Akhenaten's efforts have historically been viewed as a sincere effort at religious reform, he was most likely motivated by the great wealth of the Priests of Amun, who, at the time he ascended to the throne, held more land and greater wealth than the pharaoh.

SIGNIFICANCE & CULT

Once Amun was identified as the most powerful deity in the universe he acquired epithets which described his various aspects as best they could. Wilkinson writes how "the Egyptians themselves called him Amun asha renu or 'Amun rich in names,' and the god can only be fully understood in terms of the many aspects which were combined in him" (92). He was known as "The Concealed God" - he whose nature could not be known and associated with air or the wind which can be felt but not seen or touched. He was also the Creator God who originally stood on the first dry ground at the beginning of time and created the world by mating with himself.

Amun

Once he was linked with Ra to become Amun-Ra, he took on Ra's aspects as a solar god and, as one would expect from a creator, was also a fertility god linked with the fertility deity Min (a very ancient god) and known in this regard as Amun-Min. As he had absorbed the attributes of the war god Montu of Thebes, he was regularly invoked in battle (as Ahmose I had done) and so was also a war god. His mysterious nature infused and gave form to all that human beings could see and all that remained hidden from sight and so he was also a universal god, the most powerful in the universe and, naturally, the King of the Gods. Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch writes:

In his chief cult temple at Karnak in Thebes, Amun, Lord of the Thrones of the Two Lands, ruled as a divine pharaoh. Unlike other important deities, Amun does not seem to have been thought of as living in some distant celestial realm. His presence was everywhere, unseen but felt like the wind. His oracles communicated the divine will to humanity. Amun was said to come swiftly to help Egyptian kings on the battle field or to aid the poor and friendless. When he was manifest in his cult statues, Amun periodically visited the necropolis of Thebes to unite with its goddess, Hathor, and bring new life to the dead. (100-101)

Amun in the New Kingdom rapidly became the most popular and most widely venerated deity in Egypt. Wilkinson notes that "the monuments which were built to him at that time were little short of astounding and Amun was worshipped in many temples throughout Egypt" (95). The main Temple of Amun at Karnak is still the largest religious structure ever built and was connected to the Southern Sanctuary of the Luxor Temple. The ruins of these temples, and many others to Amun, may still be seen today but there was also a floating temple at Thebes known as Amun's Barque which was said to be among the most impressive works created for the god.

Amun's Barque was known to the Egyptians as Userhetamon, "Mighty of Brow is Amun," and was a gift to the city from Ahmose I following his victory over the Hyksos and ascension to the throne. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson writes, "It was covered in gold from the waterline up and was filled with cabins, obelisks, niches, and elaborate adornments" (21). On Amun's great festival, The Feast of Opet, the barque would move with great ceremony - carrying Amun's statue from the Karnak temple downriver to the Luxor temple so the god could visit. During the festival of The Beautiful Feast of the Valley, which honored the dead, the statues of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu (the Theban Triad) traveled on the ship from one side of the Nile to the other in order to participate.

On other days the barque would be docked on the banks of the Nile or at Karnak's sacred lake. When not in use, the ship would be housed in a special temple at Thebes built to its specifications, and every year the floating temple would be refurbished and repainted or rebuilt. Other barques of Amun were built elsewhere in Egypt, and there were other floating temples to other deities, but Amun's Barque of Thebes was said to be especially impressive.

THE PRIESTS OF AMUN & PHARAOH AKHENATEN

The kind of wealth King Ahmose I had at his command to enable him to build the elaborate barque for Amun would eventually appear miniscule when compared to the riches amassed by the priests of Amun at Thebes and elsewhere. By the time of Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE) the priests owned more land, had more cash on hand, and were almost as powerful as the pharaoh. Amenhotep III introduced religious reforms in an attempt to curb the power of the priesthood, but they were fairly ineffective.

His most significant reform was the elevation of a formerly minor deity, Aten, to his personal patron and encouraged the worship of this god alongside Amun. The cult of Amun was unaffected by this, however, and continued to grow. Aten was already associated with Amun and with Ra as the solar disc representative of the sun's divine power. The symbol of Aten simply became another way in which to express one's devotion to Amun, and the priests continued to live their comfortable lives of privilege and power.

Amun & Tutankhamun

This situation changed dramatically when Amenhotep IV (1353-1336 BCE) succeeded his father as pharaoh. For the first five years of his reign Amenhotep IV followed the policies and practices of his father but then changed his name to Akhenaten (meaning "successful for" or "of great use to" the god Aten) and initiated dramatic religious reforms which affected every aspect of life in Egypt. Religious life was intimately tied to one's daily existence and the gods were a part of one's work, one's family, and one's leisure activities.

The people relied on the temples of the gods not just as a source of spiritual comfort and security but as places of employment, food depots, doctor's offices, counseling centers, and shopping centers. Akhenaten closed the temples and forbade the traditional worship of the gods of Egypt; he proclaimed Aten the one true god and the only deity worthy of veneration.

He had a new city built, Akhetaten, and abandoned Thebes as his capital. Historian Marc van de Mieroop comments on this, writing :

With the move to Akhetaten, Akhenaten no longer just ignored the other gods of Egypt, but started to persecute them, especially Amun, whose name and images he had removed...many people continued their previous religious practices in private although no official cults but Aten's were tolerated. (203)

When Akhenaten died in 1336 BCE, his son Tutankhaten took the throne, changed his name to Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BCE), and moved the capital of Egypt back to Thebes. He reinstated the old religion and opened all the temples. On his death, the general Horemheb (1320-1292 BCE) ruled as pharaoh (after a brief power struggle) and obliterated the memory of Akhenaten and his family from the historical record as he raised the old gods to their former heights. The power of the Aten cult and Akhenaten's religious movement seems to have continued, however, and it has been suggested that the great Hebrew law-giver Moses was a priest of Aten who left Egypt with his followers to establish a monotheistic community elsewhere. This theory is explored in depth in Sigmund Freud's work Moses and Monotheism.

THE CONTINUED POPULARITY OF AMUN

After the reign of Horemheb, Amun's cult continued on as it had before and was just as popular. It gained widespread acceptance throughout the 19th Dynasty of the New Kingdom and, by the time of the Ramessid Period (c. 1186-1077 BCE) the priests of Amun were so powerful they were able to rule Upper Egypt from Thebes as pharaohs. The power of the priests of Amun, in fact, is a major factor in the fall of the New Kingdom. The Cult of Amun continued to exercise control from Thebes during the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE) even as the Cult of Isis gained more followers.

A custom elevated by Ahmose I was the consecration of royal women as "divine wives of Amun" who would officiate at festivals and ceremonies. This position existed prior to Ahmose I but he turned the office of God's Wife of Amun into one of great prestige and power. This position was given even greater importance later and, Wilkinson writes, "the Kushite kings of the 25th dynasty continued this practice and their rule actually led to a resurgence in the worship of Amun as the Nubians had accepted the god as their own" (97). When the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal sacked Thebes in 666 BCE Amun was worshiped widely throughout Egypt, and afterwards, the god remained just as popular. Wilkinson notes,

The worship of Amun also extended to the non-formal veneration of popular religion. The god was regarded as an advocate of the common man, being called "the vizier of the humble" and "he who comes at the voice of the poor" and as "Amun of the Road" he was also regarded as the protector of travellers. (97)

Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) had once claimed Amun was her father and thereby legitimized her reign. Alexander the Great would do the same in 331 BCE at the Siwa Oasis, proclaiming himself a son of the god Zeus -Ammon, the Greekversion of the god. In Greece, Zeus-Ammon was depicted as the full-bearded Zeus with the ram's horns of Amun and associated with power and virility through imagery including the bull and the ram. The god was taken to Rome as Jupiter -Ammon where he was venerated for the same reasons as elsewhere.

Zeus Ammon

Amun's popularity declined overall in Egypt as Isis became more popular, but he was still worshiped regularly at Thebes even after the city fell into ruin following the Assyrian invasion. His cult took hold especially in the region of the Sudan where, as in Egypt, his priests became powerful and wealthy enough to enforce their will on the kings of Meroe. As in the Amarna Period of Egypt 's history, when Akhenaten moved against the priests of Amun, King Ergamenes of Meroe could no longer tolerate the power of the priests of Amun in his country and had them massacred c. 285 BCE, thereby breaking ties with Egypt and establishing an autonomous state.

Amun continued to be revered in Meroe and elsewhere, however, as a potent deity. The cult of Amun would continue to attract followers well into the period known as classical antiquity (c. 5th century CE) when, like all the old gods, he was eclipsed by the new religion of Christianity.

Anaximander › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

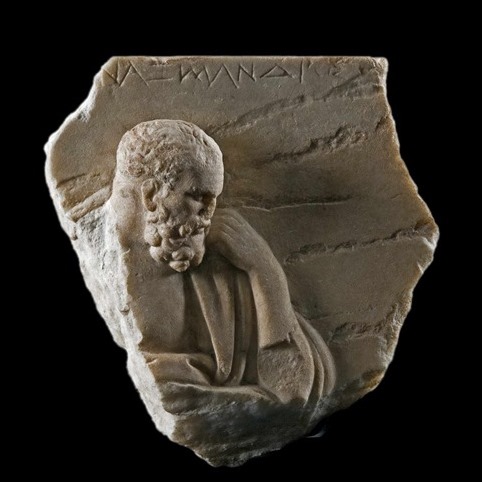

Anaximander (c 610 - c 546 BCE) of Miletus was a student of Thales and recent scholarship argues that he, rather than Thales, should be considered the first western philosopher owing to the fact that we have a direct and undisputed quote from Anaximander while we have nothing written by Thales. Anaximander invented the idea of models, drew the first map of the world in Greece, and is said to have been the first to write a book of prose. He traveled extensively and was highly regarded by his contemporaries. Among his major contributions to philosophical thought was his claim that the 'basic stuff' of the universe was the apeiron, the infinite and boundless, a philosophical and theological claim which is still debated among scholars today and which, some argue, provided Plato with the basis for his cosmology.

Simplicius writes,

Of those who say that it is one, moving, and infinite, Anaximander, son of Praxiades, a Milesian, the successor and pupil of Thales, said that the principle and element of existing things was the apeiron [indefinite or infinite] being the first to introduce this name of the material principle. He says that it is neither water nor any other of the so-called elements but some other apeiron nature, from which come into being all the heavens and the worlds in them. And the source of coming-to-be for existing things is that into which destruction, too, happens 'according to necessity; for they pay penalty and retribution to each other for their injustice according to the assessment of time,' as he describes it in these rather poetical terms. It is clear that he, seeing the changing of the four elements into each other, thought it right to make none of these the substratum, but something else besides these; and he produces coming-to-be not through the alteration of the element, but by the separation off of the opposites through the eternal motion. ( Physics, 24)

This statement by Anaximander regarding elements paying penalty to each other according to the assessment of time is considered the oldest known piece of written Western philosophy and its precise meaning has given rise to countless articles and books.

ANAXIMANDER THE MILESIAN, A DISCIPLE OF THALES, FIRST DARED TO DRAW THE INHABITED WORLD ON A TABLET.

Thales claimed that the First Cause of all things was water but Anaximander, recognizing that water was another of the earthly elements, believed that the First Cause had to come from something beyond such an element. His answer to the question of `Where did everything come from?' was the apeiron, the boundless, but what exactly he meant by `the boundless' has given rise to the centuries-old debate. Does `the boundless' refer to a spatial or temporal quality or does it refer to something inexhaustible and undefined?

While it is impossible to say with certainty what Anaximander meant, a better understanding can be gained through his `long since' argument which Aristotle phrases this way in his Physics,

Some make this [First Cause] (namely, that which is additional to the elements) the Boundless, but not air or water, lest the others should be destroyed by one of them, being boundless; for they are opposite to one another (the air, for instance, is cold, the water wet, and the fire hot). If any of them should be boundless, it would long since have destroyed the others; but now there is, they say, something other from which they are all generated.(204b25-29)

In other words, none of the observable elements could be the First Cause because all observable elements are changeable and, were one to be more powerful than the others, it would have long since eradicated them. As observed, however, the elements of the earth seem to be in balance with each other, none of them holding the upper hand and, therefore, some other source must be looked to for a First Cause. In making this claim, Anaximander becomes the first known philosopher to work in abstract, rather than natural, philosophy and the first metaphysician even before the term `metaphysics' was coined.

Anaximander has been credited with a proto-theory of evolution, as these passages attest:

Anaximander said that the first living creatures were born in moisture, enclosed in thorny barks and that as their age increased they came forth on to the drier part and, when the bark had broken off, they lived a different kind of life for a short time (Aetius, V, 19).

He says, further, that in the beginning man was born from creatures of a different kind because other creatures are soon self-supporting, but man alone needs prolonged nursing. For this reason he would not have survived if this had been his original form ( Plutarch, 2).

And, further, is credited with drawing the first map:

Anaximander the Milesian, a disciple of Thales, first dared to draw the inhabited world on a tablet; after him Hecataeus the Milesian, a much travelled man, made the map more accurate, so that it became a source of wonder (Agathemerus, I, i).

He charted the heavens, traveled widely, was the first to claim the earth floated in space, and the first to posit an unobservable First Cause (which, whether it influenced Plato, certainly shares similarities with Aristotle's Prime Mover). Diogenes Laertius writes, "Apollodorus, in his Chronicles, states that in the second year of the fifty-eighth Olympiad, [Anaximander] was sixty-four years old. And soon after he died, having flourished much about the same time as Polycrates, the tyrant, of Samos." A statue was erected at Miletus in Anaximander's honor while he lived and his legacy still lives on centuries after his death.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License