Battle of Telamon › Alcestis › Alcibiades » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Battle of Telamon › Origins

- Alcestis › Who was

- Alcibiades › Who was

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Battle of Telamon › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

Ever since the 4th century BCE, the Gallic tribes of northern Italy clashed with the expanding Roman Republic. In 225 BCE, the Boii forged alliances with fellow Gallic tribes of northern Italy and with tribes from across the Alps. The pan -Gallic army struck for Rome, but they were intercepted by three mighty Roman armies. Trapped at Cape Telamon, the outnumbered Gauls put up a hard fight but were ultimately defeated. The battle of Telamon marked the decline of Gallic fortunes in the warwith Rome for northern Italy.

PROLOGUE

After burning and sacking Rome in 390 BCE, the Gallic tribes of northern Italy repeatedly clashed with the resurgent and expanding Roman Republic. Rome took the war to the Gauls and in 284 BCE vanquished the Senones and utterly devastated their lands (modern Romagna). The powerful Boii, who lived north of the Senones, in turn invaded the Roman heartland. The Boii suffered defeats, however, and in 282 BCE agreed to a peace treaty.

Gallic Wars

50 years passed before the Senones lands recovered sufficiently for the settlement of Roman citizens. The establishment of the Roman colony of Sena Gallacia along the coast worried the Boii, who justifiably feared further Roman inroads into GalliaCisalpina ( Gaul south of the Alps). A new generation of Boii had grown up, “full of unreflecting passion and absolutely without experience in suffering and peril” ( Polybius, The Histories, II. 21). They were ready to renew the war with Rome. The Boii looked for help from Gallic tribes north of the Alps (Gallic Transalpina), but their first attempt ended in a quarrel during which two of the Transalpina kings were killed. In north-western Italy, however, the powerful Insubres were ready to fight with the Boii.

Together the Boii and Insubres sent ambassadors across the Alps, this time soliciting help from the Gaesatae who dwelt near the Rhone. The ambassadors enticed the Gaesatae kings Concolitanus and Aneroestus with tales of Gallic valor and gifts of gold, a small sample of what could be looted from the Romans. “On no occasion has that district of Gaul sent out so large a force or one composed of men so distinguished or so warlike,” wrote Polybius (Polybius, The Histories, II. 22).

PREPARATION FOR WAR

In 225 BCE, the Gaesatae crossed the Alps to join their allies - now including a contingent of Taurisci from the Alps' southern slopes - on the Po River plain. Not all the tribes of Gallia Cisalpina wanted war with Rome, though. The pro-Roman Veneti and Cenomani threatened the lands of the tribes marching off to fight Rome. The Boii coalition thus had to ensure that enough warriors remained behind to protect their homelands. Even so, the army that assembled was the biggest the pan-Gallic army ever to march on Rome, with over 20,000 cavalry and 50,000 infantry.

THE ARMY THAT ASSEMBLED WAS THE BIGGEST THE PAN-GALLIC ARMY EVER TO MARCH ON ROME, WITH OVER 20,000 CAVALRY & 50,000 INFANTRY.

Unlike two centuries ago when Rome was sacked by the Gauls, Rome was no longer a mere city-state but a republic that had laid the foundation of an empire. After consolidating its hold on peninsular Italy, Rome emerged victorious in the First Punic War (264-241 BCE) and established itself as a major power in the Mediterranean. Tempered in battle with a myriad of nations, the Roman army had become bigger and better.

The threat of the Gallic army terrified all of peninsular Italy into raising tens of thousands of soldiers to aid the Romans. Allied Sabines, Samnites, Lucanians, Marsi and a host of other infantry and cavalry, joined the Roman legions. Over 150,000 men stood ready to fight under the Roman banner, stationed in three armies; in Etruria, on the Adriatic coast, and on Sardinia.

AMBUSH AT FAESULAE

The Gauls entered Etruria over a path in the northern Apennines Mountains. Having encountered no opposition, they plundered along the way to Rome. They were within three days of the city when their scouts reported that a large Roman army was behind them. It was the one from Etruria, and by sunset, it had drawn into the sight of the Gauls.

As both armies settled down to camp for the night, the Gauls contemplated what to do. The Roman army must have been of considerable size, for instead of offering battle the Gauls came up with a ruse. At night the Gallic infantry departed towards the nearby town of Faesulae. The cavalry remained behind at the campfires so that in the morning the Romans did not know where the Gallic infantry had gone. Assuming the latter had fled, the Romans advanced on the Gallic cavalry, which took off towards Faesulae. Following in pursuit, the Romans were ambushed by the Gallic infantry attacking out of the woods and shrubs near Faesulae. The Gallic cavalry now wheeled around so that the Romans were caught between infantry and cavalry.

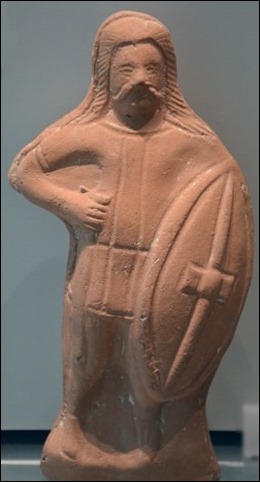

Celtic Warrior

The Romans were now in a real bind, but discipline and training paid off. The legions and their allies were able to carry out a fighting retreat. Although they suffered a loss of 6,000, the bulk of the army was able to reach a defensible position on a nearby hill. Here they fought off the Gauls, who, having slept little the night before, were further exhausted by fighting uphill.Unable to dislodge the Romans, the Gauls fell back and retired to recuperate from the fighting, leaving some cavalry to keep an eye on the Romans.

Meanwhile, Consul Lucius Aemilius Papus, commander of the Roman army on the Adriatic, got wind of the Gallic inroads and force-marched his men over the Apennines. He arrived just after the battle at Faesulae. As night was descending upon the land, Papus set up camp. His arrival naturally encouraged the Romans on the hill and, conversely, presented a major problem for the Gauls. Since the Gauls had already taken numerous slaves, cattle, and plunder, King Aneroestes of the Gaesatae thought that it would be wiser to return to their homelands with what they already had and return to deal with the Romans at a later date. Thus, at night, the Gallic army once again slipped away into the darkness. Blocked by the Romans to the north and by wooded hills to the east and west, the Gauls headed south.

The next day the two Roman armies combined and followed the retreating Gauls. When the terrain opened up at Lake Bolsena, the Gauls struck west for the Eturian coast. Once they reached the coast, they headed back north, hoping to reach the River Po and their homelands. The Roman army, just as cumbersome with its own supply train, draft animals, livestock, and hangers-on, followed in the Gallic army's wake.

CAPE TELAMON

By this time, the third Roman army from Sardinia had sailed north, past Corsica, and crossed to the mainland landing at Pisae.Probably at this point, the Roman army commander, Consul Gaius Atilius Regulus realized that the Gauls were no longer a threat to Rome but had taken captives and plunder and were trying to escape back to their homelands. Regulus marched south, hoping to intercept the Gauls. A Roman reconnaissance party scouted ahead and captured Gallic scouts who were forced to divulge the current position of their army. Regulus was pleased; the Gallic army would be squeezed and annihilated between two Roman armies. He ordered his tribunes to march forward in fighting order.

Between the Roman and Gallic armies, in the vicinity of Cape Telamon, a gentle hill rose beside the road. Eager to gain the hill before the Gauls, Regulus personally led his cavalry toward the hill. The Gallic army was still not aware of the new Roman threat from the north. Espying the Roman cavalry headed for the hill, the Gauls thought that they had been outflanked by Papus' cavalry coming from behind. The Gauls sent their own cavalry and light skirmishers to take the hill and took some prisoners in the fight. The prisoners told them the grim truth; they were about to get caught between two gigantic Roman armies.

Roman Cavalryman

This time there was no escape for the Gauls. The Boii and Taurisci formed up to meet Regulus' army approaching from ahead.The Gaesatae and Insubres wheeled to face Papus' army coming up from behind. The Gallic chariots and wagons formed up on the flanks while a small detachment took the booty to the neighboring hills.

On the roadside hill, the cavalry melee raged on. Regulus was struck a mortal blow, and the macabre trophy of his head was carried back to the Gallic kings. The Gauls, however, had little time to gloat about Regulus' death for Papus' army forthwith arrived on the scene. Papus drew up his legions to face the Gauls and sent his cavalry to aid the Roman cavalry engaged on the hill.

The Roman infantry now sized up their foes. While they were well trained and armed, the Roman legionaries were citizens levied from the population during times of war. Though honor-bound to fight for Rome, they were not professional soldiers. To them, the enemy were savage barbarians.

[The Romans] were terrified by the fine order of the Celtic host and the dreadful din, for there were innumerable horn-blowers and trumpeters, and, as the whole army were shouting their war-cries at the same time, there was such a tumult of sound that it seemed that not only the trumpets and the soldiers but all the country round had got a voice and caught up the cry. (Polybius, The Histories, II. 29)

The tall, tawny, and red-haired Gallic warriors worked up their courage, shouting and gesturing with their spears, swords, and shields. The latter was their main defense, usually being oval and painted with swirling patterns. Many also wore bronze helmets, adorned with horns, plumes, or the Celtic symbol of war, the wheel. Only the chiefs and warriors of note boasted mail armor. Most wore the typical multicolored, checkered trousers and cloaks popular among the Gauls. Not so the Gaesatae, who in a show of courage and oneness with nature went into battle naked, wearing only their torques, armlets and bracelets.

The Roman consuls opened the battle with the light troops which streamed through the gaps of the maniples, the 60-120-men-strong primary tactical units of the Roman legions. Thousands of troops wearing wolf, badger, and other animals skins on their helmets, and carrying small round shields, hurled their small javelins upon the front rank of the Gauls. The spears and slings of the Gauls lacked the range to fire back, and so the Gallic warriors crouched behind their large shields while the deadly Roman missiles whistled among them. The naked Gaesatae suffered most of all. Enraged at their impotence, the bravest of them charged forward but were impaled by javelins before they could close in on their foes.

Gallic Warriors

Trumpets blared, and the ground shook beneath the tramp of tens of thousands of legionaries as the maniples advanced upon the Gallic horde. The first manipli line, the hastati, unleashed another javelin volley upon the Gauls. The iron heads of their heavy pilum javelin were barbed and remained stuck in the Gallic shields. While the Gauls tried to pry the javelins out of their shields the hastati drew their short swords and charged.

The Gauls swung their powerful swords in great arcs, splintering shields, and biting into the bronze of the Roman helmets. The Romans, in turn, stabbed with their short swords. Needing less space per warrior, they presented a tighter shield wall. The Romans enjoyed the further advantage in that their oblong scutum, a shield bent backward, enclosing part of the bearer's body. Below the shield, the exposed forward Roman leg was protected by greaves. The hastati also wore breastplates while the second and third Roman lines, the principes and triarii, wore chainmail.

With skill, brute force, and courage, the outnumbered and surrounded Gauls held on. For a while it even looked like the battle could go either way. However, the cavalry battle on the hill had already ended in a Roman victory. The Gallic cavalry had fled, leaving the Roman horsemen free to come to the aid of their comrades on the plain below. Down the hill the Roman horses thundered, their spears slicing into the flanks of the Gallic infantry. The Gauls broke in panic but, hemmed in from all sides, were cut to pieces.

AFTERMATH

40,000 Gauls were killed and 10,000 captured for the slave markets. Among the captives was King Concolitanus. King Aneroestes escaped but overcome by grief ended up taking his own life. Papus sent the Gallic booty to Rome, to be returned to its owners. He then led his army towards the lands of the Boii to exact vengeance, burning and killing. Papus returned home to celebrate a Roman triumph, displaying his loot and captives.

In a series of campaigns that followed the battle at Telamon, the Romans shattered Gallic resistance in northern Italy. After the Roman victory at Clastidium, in 222 BCE, most of the Gauls submitted to Roman rule. Gallic resistance revived with Hannibal's invasion of Italy and continued for another ten years after the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE). The Boii were the last to give up in 191 BCE. Refusing to live under the Roman yoke, they wandered to the Danube region where they gave their name to Bohemia. Roman roads and colonies spread across Gallia Cisalpina, which by the mid-2nd century BCE had already become Italianized.

Alcestis › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Alcestis was the mythical queen of Thessaly, wife of King Admetus, who came to personify the devoted, selfless, woman and wife in ancient Greece. While the story of Admetus' courtship of Alcestis was widely told, she is best known for her devotion to her husband in taking his place in death and her return to life through the intervention of the hero Herakles (better known as Hercules ). There are two versions of Alcestis' story, one in which Hercules plays no part at all, but thanks to the playwright Euripides (480-406 BCE), and his play Alcestis (written 438 BCE) the version featuring Hercules is the better known.

ALCESTIS & ADMETUS

Both versions begin the same way and emphasize the importance of loyalty, love, and kindness. Once upon a time there lived a gentle king named Admetus who ruled over a small kingdom in Thessaly. He knew each of his subjects by name and so, one night when a stranger appeared at his door begging for food, he knew the man must be from a foreign land but welcomed him into his home anyway. He fed and clothed the stranger and asked him his name, but the man would give no answer other than to ask Admetus if he could be the king's slave. Admetus had no need for another slave but, recognizing the man was in distress, took him on as shepherd for his flocks.

IN THE OLDER VERSION OF THE STORY, ADMETUS WAKES ON HIS BED FEELING BETTER AND RUNS TO TELL ALCESTIS HE IS CURED, ONLY TO FIND IT WAS SHE WHO TOOK HIS PLACE IN THE UNDERWORLD.

The stranger stayed with Admetus for a year and a day and then revealed himself as the god Apollo. He had been sent to earth by Zeus as punishment and could not return to the realm of the gods until he had served a mortal as a slave for a year.Apollo thanked Admetus for his kindness and offered him any gift he desired, but Admetus said he had all he needed and required nothing for what he had done. Apollo told him he would return to help him whenever he needed anything in the future and then vanished.

Not long after this, Admetus fell in love with the princess Alcestis of the neighboring city of Iolcus. Alcestis was kind and beautiful and had many suitors but only wanted to marry Admetus. Her father Pelias, however, refused Admetus' request for her hand and stipulated that the only way he would give his daughter to him would be if he rode into the city in a chariot pulled by a lion and a wild boar. Admetus was despondent over this situation until he remembered the promise of Apollo. He called on the god who appeared, wrestled a lion and a boar into submission, and yoked them to a golden chariot. Admetus then drove the chariot to Iolcus, and Pelias had no choice but to give him Alcestis in marriage. Apollo was among the wedding guests and gave Admetus an unusual gift: a kind of immortality. Apollo told them how he made a deal with the Fates who governed all so that, if ever Admetus became sick to the point of death, he might be well again if someone else would volunteer to die in his place.

The couple lived happily together for many years and their court was famous for their lavish parties but then, one day, Admetus fell ill and the doctors said he would not recover. The people of his court remembered the gift of Apollo and each felt that someone should give their life to save so kind and good a king, but no one wanted to do so themselves. Admetus' parents were old and so it was thought that one of them would volunteer but, even though they had only a short time left on the earth, they refused to surrender it. None of the court, nor any of Admetus' family, nor any of his subjects would take the king's place on his death bed - but Alcestis did.

At this point the two stories diverge. In the older version, Admetus wakes on his bed feeling better and runs to tell Alcestis he is cured, only to find it was she who took his place. He then sits by her body in mourning and refuses to eat or drink for days.As this is going on, Alcestis' spirit is led down into the underworld by Thanatos (death) and presented to Queen Persephone.Persephone asks who this soul is who has come willingly to her realm, and Thanatos explains to her the situation. Persephone is so moved by the story of Alcestis' love and devotion to her husband that she orders Thanatos to return the queen to life.Alcestis and Admetus then live happily ever after.

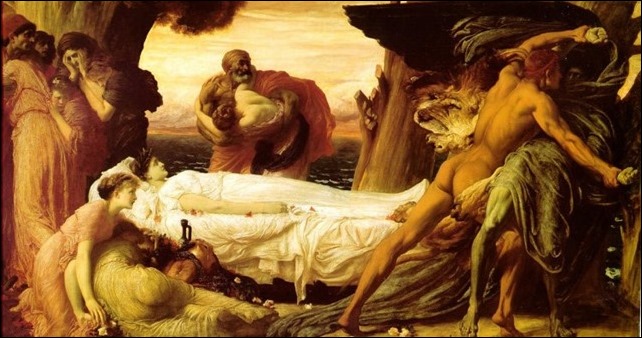

The Abduction (Hercules and Alcestis)

HERCULES & ALCESTIS

In the version popularized by Euripides in his play Alcestis, however, Hercules plays the pivotal role in bringing Alcestis back from the dead. In this version, as in the first, no one will take Admetus' place in death except for Alcestis. Admetus is informed of this, accepts her sacrifice, and begins to recover as his queen grows weaker. The entire city falls into mourning for Alcestis as she hovers on the brink between life and death. Admetus stays by her bedside and she requests that, in return for her sacrifice, he should never marry again and so keep her memory alive. Admetus agrees to this and also swears he will never throw another of their parties again nor allow any merrymaking in the palace once she has gone; after these promises are made, Alcestis dies.

Hercules was an old friend of the couple, and he arrives at the court knowing nothing of Alcestis' death. Admetus, not wishing to spoil his friend's arrival, instructs the servants to say nothing about what has transpired and to treat Hercules to the kind of party the court was known for. The servants, however, are still upset over the loss of the queen, and Hercules notices that they are not serving him and his entourage properly. After a number of drinks, he begins to insult them and ask for the king and queen to come remedy this poor performance on the servant's part, when one of the maidservants breaks down and tells him what has recently happened.

Hercules is mortified by his behavior and so travels to the underworld where Thanatos is leading Alcestis' spirit toward Persephone's realm. He wrestles death and frees the queen, bringing her back up into the light of day. Hercules then leads her to where Admetus is just returning from her funeral. He tells the king that he must depart because he is in the midst of performing one of his Twelve Labors (to bring back the Mares of Diomedes) and asks him to take care of this lady while he is gone. Admetus refuses because he promised Alcestis that he would never marry again, and it would be unseemly for this woman to reside at the court so soon after his wife's death. Hercules insists, however, and places Alcestis' hand in Admetus'.Admetus lifts the woman's veil and finds it is Alcestis returned from the dead. Hercules tells him that she will not be able to speak for three days, and will remain pale and shadow-like, until she is purified, after which time she will become as she always was. Euripides' play ends there, while other versions of the myth continue the story further and conclude with everything then happening as Hercules has said, and Alcestis and Admetus living a long and happy life together until Thanatos returns and takes them both away together.

Alcibiades › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Alcibiades (or Alkibiades ) was a gifted and flamboyant Athenian statesman and general whose shifting of sides during the Peloponnesian War in the 5th century BCE earned him a reputation for cunning and treachery. Good looking and rich, he was also notorious for his extravagant lifestyle and loose morals. Never short of enemies or admirers - amongst whom was Socrates - he was one of the most colourful leaders in the history of Classical Athens.

EARLY LIFE

Alcibiades was born in 451/450 BCE, the son of the Athenian politician Cleinias, and his mother Deinomache was from the ancient aristocratic family the Alkmeonidai. Alcibiades was also the nephew of the great Athenian statesman Pericles and he spent his childhood in the family home of his famous uncle. As a young man he was the pupil and friend of Socrates.

ALCIBIADES HELD THE POSITION OF GENERAL FOR 15 CONSECUTIVE YEARS.

In c. 420 BCE Alcibiades was made a general or strategos (at the minimum age of 30) and therefore became a member of the strategoi, the influential military council in Athens which could propose items for the agenda of the assembly. Alcibiades wasted no time in his new role and promptly negotiated an alliance between Athens, Argos, Ellis, and Mantineia, which would last 100 years. Alcibiades would go on to hold the position of strategos for 15 consecutive years.

THE SICILIAN EXPEDITION

In 415 BCE Alcibiades gave a speech to persuade the Athenians to launch a military expedition to Sicily. The pretext for this expedition occurred in 416/415 BCE when Segesta, a city-state in the west of Sicily, asked Athens for help against local rival Selinus which was allied with Syracuse. Besides imperialist ambition, Alcibiades may well have been after the timber of Sicily, an immensely important material for the Athenian navy. Alcibiades argued that the mixed race population and political instability in Sicily would make a strong and unified military response unlikely. Further, Alcibiades promised that the Persians could be persuaded to assist Athens if certain constitutional changes were made. In the end, Alcibiades won the vote of the assembly despite the doubts expressed by his rival Nikias, and the two generals, along with Lamados (or Lamachus), were given the equal status of strategoi autokratores (unlimited power) and sent, along with 6,000 men and 60 ships, to protect Segesta.

Shortly before the expedition's departure from Athens, though, Alcibiades was perhaps the victim of an infamous conspiracy.Hermai (statues with a head of the god Hermes and a large erect phallus) were damaged across the city. The sailors of the Athenian fleet, like all sailors before and since, were a superstitious lot and as Hermes was the patron of travellers, their confidence was badly affected by the attacks. In addition, according to popular opinion, the attacks on the hermai were somehow connected to an attack on the democratic system of Athens. Alcibiades, known as one of the frivolous and impious 'golden youth' of the aristocracy, was held as the prime suspect along with several others. To make matters worse, Alcibiades also faced the more serious accusation of profaning the Mysteries of Eleusis during a drinking party or symposium. Perhaps confident he would prove his innocence, Alcibiades called for an immediate trial, but the city procrastinated and he was sent to Sicily anyway. However, Alcibiades was soon officially recalled to Athens to face the court's guilty verdict. Given that punishment was the death sentence, it is perhaps not surprising that Alcibiades at this point fled to Sparta rather than face the music at home.

Magna Graecia

ADVISING SPARTA

Alcibiades made himself useful to his new hosts and, according to his accusers in Athens, he freely gave Athenian state secrets to the Spartans. He also advised the Spartans to take by force the Athenian fortress of Dekeleia (which they did in 413 BCE). Meanwhile, the Athenian expedition in Sicily was a complete disaster with total defeat in 414 BCE and the loss of Nikias and the gifted general Demosthenes. According to Xenophon, Alcibiades had advised the Spartans to send the general Gylippos to aid the besieged Sicilians. However, Alcibiades soon fell out of favour at Sparta, in particular with King Agis, and so he joined the Persian Satrap Tissaphernes ( Persia had been giving aid to Sparta so that they might build a fleet to rival Athens). Alcibiades encouraged Persia to keep on friendly terms with both Athens and Sparta, and yet at the same time Alcibiades attempted to convince the Athenian fleet based on Samos that he was the man to negotiate an Athenian-Persian alliance. Alcibiades knew that this would only be possible if an oligarchy gained political control in Athens. To this end Peisandros was sent to Athens where he persuaded the disgruntled aristocrats to attempt a coup d'état. This was successful, and so democracy gave way to an oligarchy of 400. Alcibiades was made strategos by the navy at Samos (who were actually pro-democracy) and despite the 400 being replaced by a wider oligarchy of 5000 in Athens, he led the fleet to victory over the Spartans at Cyzicus on the Hellespont in 410 BCE. Other victories included the defeat of the Persian Satrap Pharnabazos at Abydos and the taking of Byzantium.

A RETURNING HERO

In c. 407 BCE Alcibiades returned to Athens in triumph, the old charges against him were dropped, and as a reward for his efforts he was made strategos autokrater once again but this time above all other generals, the only such instance in the history of Athens. In effect then, Alcibiades was now commander-in-chief of the Athenian armed forces. Quashing a rebellion at Andros was followed by an expedition to fight the poleis of northern Ionia. Whilst occupied there, Alcibiades left Antiochosin charge of the fleet at Samos. Unfortunately for Athens, the Spartan commander Lysander took advantage of Alcibiades' absence and soundly defeated the Athenian navy at Notium (or Notion) in 406 BCE. Alcibiades was blamed for negligence in leaving only a helmsman in charge of the main fleet and was not re-elected strategos. Consequently, he left to live in Thrace, whilst the Spartans went on to finally win the Peloponnesian War in 404 BCE with Lysander's victory over the Athenian fleet at Aigospotamoi. In the same year, after taking final refuge with the Persian Pharnabazus, Alcibiades was murdered in Phrygiapossibly following the intervention of Lysander and the Thirty Tyrants of Athens.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License