Leo V the Armenian » Gela » The Book of Jonah » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions » Contents

- Leo V the Armenian » Who was

- Gela » Origins

- The Book of Jonah » Origins

Ancient civilizations » Historical places, and their characters

Leo V the Armenian » Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Leo the V the Armenian was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 813 to 820 CE. He was of Armenian descent and the last ruler of the Isaurian dynasty which had been founded by Leo III (r. 717-741 CE). The emperor’s reign, after early military successes against the Bulgars, is chiefly remembered for beginning the second wave of iconoclasm in the Byzantine Church, that is the destruction of religious icons and treating those who worshipped them as heretics.

SUCCESSION

Emperor Michael I Rangabe (r. 811-813 CE), was a big spender on churches and monasteries but in warfare he proved hopeless. Defeats to Krum, the Khan or leader of the Bulgars (r. 803-814 CE), and a mutiny within his own army meant that Michael’s days were numbered. The general Leo was selected as a figure more suitable to defend the empire in these troubled times. Leo, an Armenian of humble origins, had risen in the Byzantine army by sheer talent to eventually become the strategos or military governor of the province (theme) of Anatolikon, the most important region of Asia Minor and a vital bulwark against the invading Arabs. Leo pushed events to a crisis in June 813 CE at the battle of Versinicia near Adrianople. Facing a Bulgar army, Leo and his Anatolian troops withdrew from the field, leaving the remaining Macedonian troops to be slaughtered. The Bulgar army then marched to Constantinople and camped by the Theodosian Walls of the city.Michael abdicated and fled to seek refuge in a church; he avoided the awful fate of most Byzantine emperors who lost their throne to a usurper, but his male children were castrated and his wife and daughters sent to a convent to make sure none ever tried to reassert their claim to the throne. Michael himself was banished to a monastery on an island in the Marmara and Leo was proclaimed Emperor Leo V.

THE BULGARS TORCHED THE EXTENSIVE SETTLEMENTS, MONASTERIES & CHURCHES WHICH LAY BEYOND THE PROTECTION OF CONSTANTINOPLE’S WALLS.

KRUM & THE BULGARS

The new emperor’s immediate task was to deal with the capital’s new neighbours in the Bulgar army camp, but neither side ever doubted the impregnability of the Theodosian Walls. Instead, then, of a futile siege, Krum demanded a huge ransom in gold with a bonus batch of the most beautiful women the Byzantines could round up. Leo offered to meet Krum in person, unarmed and accompanied only by a handful of retainers, where the city’s fortifications ran down into the sea. It was a trick, of course, and three of the emperor’s henchman tried to kill the Bulgar leader. Krum managed to escape on his horse but was wounded, nevertheless. He became, understandably, intent on exacting some sort of terrible revenge. The next day the Bulgars torched the extensive settlements, monasteries and churches which lay beyond the protection of the capital’s walls. Any individuals still in the area were killed without mercy, and the Bulgar army withdrew leaving a trail of destruction as they marched back home. Entire towns and villages were wiped out, notably the city of Adrianople whose 10,000 inhabitants were taken prisoner and marched across the Danube.Proclamation of Leo V the Armenian

Leo responded with a surprise attack on a Bulgar army camped near Mesembria on the Black Sea coast of Bulgaria. Leading, as always, his army in person, the emperor crushed the enemy and, advancing deeper into Bulgar territory, ruthlessly butchered the civilian populations he came across, including women and children. Outraged, Krum decided to attack Constantinople after all in the early spring of 814 CE, regardless of the city’s formidable defences. Fully aware of the task ahead, the Bulgar Khan made meticulous preparations and amassed the necessary siege engines, catapults, and battering rams. It was all to no avail, though, as Krum died unexpectedly of a seizure (probably a stroke), and his successor, his young son Omortag, had enough on his plate dealing with a rebellion of his own aristocracy at home and the Franks threatening his western frontier to worry about the near-impossible task of taking Constantinople. The Bulgar army returned home, and a peace treaty was signed which re-established the borders of 780 CE. Gradually, the ravaged cities in Thrace and Macedonia were rebuilt by Leo, who proved something of an able administrator besides a gifted general. With the empire’s other major enemy of the period, the Arab Caliphate, similarly incapacitated by internal strife, Leo was finally able to turn his attention to his own domestic affairs.ICONOCLASM

For many Byzantine rulers, the biggest ideological challenge to their rule and number one enemy was those in the Christian church who supported the veneration of icons. Leo was to be no different, even if most of the discord was of his own doing. In 815 CE, following a council of Church elders convened by the learned Armenian monk John (VII) Grammatikos in Constantinople, Leo began a second wave of iconoclasm in the Byzantine Church (the first having occurred between 726 and 787 CE), whereby all prominent religious icons were destroyed and those who venerated them were persecuted as heretics.The motivation for the emperor to support iconoclasm, as it had been for his predecessors like Constantine V (r. 741-775 CE), besides being an obvious way to exert imperial authority over the Church in general, was the belief that a string of military defeats was God’s punishment for venerating idols. The belief was strengthened when certain victories came during the first wave of iconoclasm and during this second wave, too, there were modest victories for Byzantine armies against the Bulgars. Leo himself may not have held such convictions, but enough members of the army and peasantry did to make the issue a possible source of unrest if the emperor did not make some sort of move against the iconophiles.

Byzantine Iconoclasm

Initial opposition to the new policy was led by the Patriarch (Bishop) of Constantinople, Nikephoros I, who refused to sign the formal decree of iconoclasm issued by the council. Nikephoros was promptly replaced by the more sympathetic Theodotos I Kassiteras. Amongst the most prominent victims of the second persecution were the monks Theodore Graptos, who had his forehead branded for his beliefs, and Theophanes the Confessor, author of the Chronographia, a celebrated history of Byzantium from the 3rd to 9th century CE. The reign of terror against iconophiles would not end until 843 CE, the movement to rid the Church of icons ultimately losing imperial backing and being unable to convince the majority of Christians who continued to venerate icons privately anyway.DEATH & SUCCESSORS

Leo had always rewarded his supporters in the army so that ambitious men like Thomas the Slav, Manuel and Michael the Amorian were promoted to the top military positions of the empire. However, this policy backfired somewhat when Michael, Leo’s oldest and closest ally, had the emperor murdered in the chapel of the Great Palace of Constantinople on Christmas Day in 820 CE. Actually, Michael was rather pushed into his dramatic action as he had just been condemned to death by Leo the day before - the novel method decided upon involved tying the victim to an ape and putting the pair into the furnaces which heated the palace baths. Michael, accused of plotting a rebellion, was saved from this ignominious end by his supporters who disguised themselves as a choir of monks and butchered the emperor. Leo proved not such an easy target, though, and he defended himself with a large metal cross for an hour before finally succumbing to the assassins.Michael II was released from his prison and immediately crowned, still wearing his chains as no one could find the keys. Meanwhile, Leo’s mutilated body was dragged naked around the Hippodrome of Constantinople for public ridicule. Michael, having gained the throne for no other reason than personal ambition, would found the Amorion dynasty and reign until 829 CE when he was succeeded by his son Theophilos (r. 829-842 CE) who vehemently continued the persecution of iconophiles.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.

Gela » Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Salvatore Piccolo

Gela (Greek: Ghélas), in southern Sicily, was a Greek colony founded c. 689 BCE and it remained an important cultural centre throughout antiquity. Prospering on trade and expanding its territory, the city-state founded Agrigento. In the 5th century BCE the tyrant Gelon reigned with success but the end of that century brought attacks and destruction by Carthage. The city revived thanks to the Corinthian general Timoleon but was destroyed in 282 BCE by Phintias, ironically the tyrant of Agrigento.

FOUNDATION

Gela is located on a long and low hill running parallel to the Mediterranean sea on the southern coast of Sicily. The first settlements in the area date back to the copper age (2800-2170 BCE) with the town of Gela being founded c. 689 BCE by Greek colonists from Rhodesand Crete, amongst whom were Antifemo of Rhodes and Entimo of Crete. The town was initially called Lindioi and then changed to Gela shortly afterwards after the nearby river.The foundation of Gela was one of the most daring enterprises of Greek colonization in Sicily because it took possession of the island’s southern coast, dangerous for the presence of the important indigenous Sicanian and Siculis centres. When the Rhodium-Cretans landed they reduced the local people to the servile state (except perhaps the women they took as wives in the first two generations), occupied the plains and the surrounding hills, and merged the indigenous culture with their own.

IN 580 BCE, ABOUT 108 YEARS AFTER ITS BIRTH, GELA FOUNDED AKRAGAS (AGRIGENTO).

EARLY GOVERNMENT

It is documented that the new community followed the Greek social model but with their own independent government. From the start, power was concentrated in the hands of a few families, gathered in clans, who they awarded themselves political, judiciary and religious control. Around 600 BCE, this led to the first incident of stasis or civil war in Western history. In this case it was limited to the mutiny of the poor who had no political rights. This marginalised group, surely the majority, at some point abandoned the polis or city-state and took refuge in Maktorion, a few kilometres north of Gela. It was then that Teline, the ancestor of the tyrant Gelon, went to the rebels and persuaded them to return to Gela. Teline, as a reward for saving the city, was awarded the priesthood of Demeter and Kore who, he said, had suggested to him the best way to prevent a civil war. The two goddesses’ cult spread like wildfire throughout Sicily, and Gela became the centre of the religious initiatives undertaken by Teline and his descendants (including the tyrant Gelon).Map of Greek Sicily, 5th Century BCE

TERRITORIAL EXPANSION

In 580 BCE, about 108 years after its birth, Gela founded Akragas (Agrigento). The Hellenization of the Akragas by the Ghelòi (the Greek name for the inhabitants of Gela), reveals a common strategy pursued by the Siceliots (the Greek settlers in Sicily) for the conquest of western Sicily; this is proved by the fact that the Megarenses, 50 years before, had founded Selinunte (628 BCE), about 100 kilometres further west of Agrigento, already the site of a Ghelòan emporium. With the founding of Agrigento, a base was created which permitted the conquest of the western Sicilian hinterland, between the southern Imera River and the Alycos (modern Platani) River. This policy brought an expansion of Gelan territory to about 80 kilometres to the north, until Sabucina, Gibil Gabib, Monte San Giuliano; to the east, as far as Kamarina, and to the west, as said above, as far as Agrigento. Just 120 years after its foundation, the area under Gelan control reached 10,000 square kilometres.A PROSPERING POLIS

At the beginning of the 5th century BCE, Sicily was heading towards a golden period of prosperity and its city-states would play a crucial role in the Western history. Gela, thanks in particular to its skilled craft workers, had developed a rich trade network which is well documented by archaeological excavations. In the mid-sixth century BCE, the city ceased importing from Greece and acquired a degree of autonomy and expertise so that it would become famous in its own right throughout the fifth century BCE. Particularly noteworthy were the city’s temple decorations, the production of painted vases, and the making of majestic fictile (terra cotta) sarcophagi whose decoration and beauty was unparalleled in the ancient world. One splendid example of Gelan artwork is a thymiatérion or incense burner in the form of a female figurine with a bowl on her head. Although imitating other similar Aegean artifacts, in this case, the Gelan master exceeds the now frequent banality of the object, imprinting original somatic traits which make the piece unique.THE TYRANTS

Gela became famous for its tyrants and the first was Cleandro. The historical information about him, unfortunately, is fragmentary. A winner a the Olympic Games of 512/508 BCE, he came to power through a coup, overthrowing an oligarchic regime whose members declared themselves descendants of the ancient colonisers. Cleandro maintained his rule over the city with mercenaries, many of whom were Siculis, and he was killed for an unknown reason by the Ghelòan Sabillo.Charioteer of Delphi

Cleandro was followed by his brother Hippocrates, who carried out a far-sighted expansionist policy and led the city of Gela to a level of wealth which made it the most powerful city in Sicily. He died in 491 BCE, during the siege of Hybla, the stronghold of the Siculis resistance. The ambitious program of Hippocrates was continued by one of his generals, Gelon, son of Deinomenes, who will go down in history as a magnanimous and fair tyrant. Married to Demarete, daughter of Theron, the tyrant of Agrigento, Gelon was also able to make himself tyrant of Syracuse after resolving there a dispute between the rich (gamòroi) and poor (kyllýrioi). In 480 BCE Gelon defeated the Carthaginians in a memorable battle fought in Imera (today's Termini Imerese), following their attempt to conquer Sicily. Pindar, the Greek poet from Thebes who spent several years in Sicily, particularly in Syracuse and Akragas, became the lyrical spokesman of that win and its glorious victor, Gelon. The tyrant was appreciated by his people who recognised him as the "second founder" of Syracuse.When Gelon died, in 478 BCE, his place was taken by the second brother Hieron, who was in turn replaced by the third brother, Polyzelos. In 476 BCE Hieron founded Aitna (Catania) and in 472 BCE he won a great battle at Cuma against the Etruscans who had threatened the trade between Sicily and southern Italy. With the death of Hieron, which occurred in 467 BCE, power passed to the fourth brother, Thrasybulus, who was overthrown just a year later by his own family for convincing Gelon's son to give up his claim to become tyrant of Syracuse. From this moment forward, the city’s history becomes unclear.

It seems that, thereafter, there were no more tyrants at Gela and some form of democratic government was adopted. Certainly, the town must have remained an important cultural centre if, in 459 BCE, the great tragedian Aeschylus, who had left with disgust his native Athens, settled there. The playwright died in the city three years later at the age of 63. The Ghelòan people raised a monument to him on which, according to tradition (Paus. I, 14; Aten. XIV, 627), these words were engraved:

Αἰσχύλον Εὐφορίωνος Ἀθηναῖον τόδε κεύθει

μνῆμα καταφθίμενον πυροφόροιο Γέλας•

ἀλκὴν δ'εὐδόκιμον Μαραθώνιον ἄλσος ἂν εἴποι

καὶ βαθυχαιτήεις Μῆδος ἐπιστάμενος

This memorial stone covers Aeschylus Euphorion's (son),

Athenian, died in the fertile Gela: his glorious valor

the wood of Marathon could testify to it and

the long-haired Mede who knows it well.

ATHENS & CARTHAGE

In 424 BCE, Gela was still a leading city, so much so that it organised a "Peace Congress" which aimed to encourage an understanding between the forever-fighting cities of Sicily so that they could unite against a common enemy, the Athenians, who threatened to invade the whole island. The results of the congress were positive, and the Greeks, seeing that trouble was brewing, thought it appropriate to withdraw and return to their country. The Athenians launched an attack nine years later but were definitively defeated by a Siceliotic army in 412 BCE.Silver Tetradrachm of Gela

In the spring of 406 BCE the Carthaginians launched a new attack to control Sicily. An army of 300,000 men under the command of Hannibal (not the famous one) and the young Imilcone, conquered Agrigento after eight months of fighting, devastating the city and stripping it of its treasures, including the famous "brazen bull” of Phalaris that was transferred to Carthage. Agrigento’s downfall was a disaster for the Siceliotic cause because it triggered dangerous destabilising effects that culminated in many betrayals of allies, who were quick to climb on the African bandwagon. When spring of 406 BCE came, Imilcone, with an army of 120,000 men and 4,000 horsemen marched to Gela and Kamarina. The Ghelòi, confident in Syracusan assistance and in their tyrant Dionysius, prepared themselves for the battle which, unfortunately, was lost. We do not know why Dionysius decided to withdraw, permitting the destruction of Gela and causing the evacuating its population to Syracuse.HELLENISTIC REVIVAL

Gela, left uninhabited until 339 BCE, was rebuilt by Timoleon, a Corinthian general sent to Sicily to extract it out of the anarchic swamp in which it was bogged down. Under the leadership of the Greek commander, Gela received a new architectural and artistic impetus. The city rose in the western hill zone this time, utilising the ruins of the old city. Public and private buildings were reconstructed, the defensive walls were enlarged and the eastern part was used for workshops. The walls of "Caposoprano", well-known for their construction technique using squared block stones in the lower and mudbricks in the upper courses, were an enlargement of the existing defence circuit, inside which the new polis was protected. At this time a famous resident was Apollodorus, the comic poet and playwright of the "new comedy", and Archestratus, poet, philosopher and father of gastronomy, whose works reflect the well-being of the re-established Gela.Timoleon Walls, Gela

DESTRUCTION BY PHINTIAS

In 282 BCE, unfortunately, the city was definitively destroyed by Phintias, the tyrant of Agrigento, who found a new city to which he gave his own name Phintiade (today's city of Licata) and where he moved the inhabitants of Gela. This interpretation, perhaps rather too simplistic and contradictory, is reported in Diodorus Siculus' Bibliotheca historica (XXII, 2,4). The tale of Phintias' heartless attitude towards Gela seems to be simple war propaganda.In Diodorus' account, which refers to an earlier destruction of Gela just a few years before by the Mamertines, there are obvious contradictions. One wonders why Phintias should have raged on the just collapsed city. At that moment, it could not have constituted a danger to Agrigento, if it ever had been. Akragantìnoi and Ghelòi had enjoyed a long-lasting relationship based on their common origins (let us remember that Gela had founded Akragas), but also by the continuous close family bonds between the two cities ‘inhabitants. It is also unthinkable that the tyrant opened a second war front and so jeopardised the chances of victory against Syracuse. The belief that Phintias was guilty of such a hateful crime, committed against his own motherland, made him an unpopular tyrant and explained his loss of support from the other Sicilian cities (Diod., XXII, 2,6).

LATER HISTORY

Gela was not definitively abandoned, rather, in Roman times it was reduced to a modest farmer’s village. However Gela continued to be remembered for its great history: Virgil, in the Aeneid, mentions its "Campi Ghelòi" (the vast high wheat plain which was very famous in ancient times), and Cicero, Strabo and Pliny cite it in their works. The city was reborn 1,500 years later, for, in 1239 CE, Frederick II of Swabia rebuilt a new town on the same spot as the ancient settlement.The Book of Jonah » Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Benjamin T. Laie

The book of Jonah is the fifth book in the Christian canons and the Jewish Tanakh. It is one of 'Trei Asar' (The Twelve) prophets in the tanakh, and in Christian tradition as 'oi dodeka prophetai' or 'ton dodekapropheton' , Greek for "The twelve prophets." It is an important book to both religious traditions (Christianity and Jewish) because of its message of doom upon Israel's long-time enemy - Assyria, whose capital was Nineveh. However, despite the book's small size, scholars continue to dispute its content and date of composition. Some have encountered major themes in the book that does not relate to Jonah's 8th century BCE context but beyond his time. Others have pointed out the different types of Hebrew and argue that the book has been edited by generations after Jonah. This article provides a brief discussion on these issues and where the book of Jonah now stands in modern scholarly discussion.

JONAH & THE FISH

THE NAME JONAH

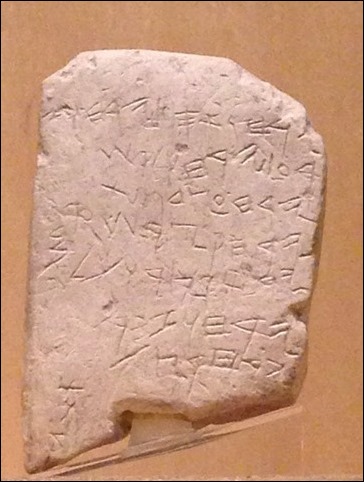

The superscription of the book provides the prophet’s full name, Jonah son of Amittai, who is the main protagonist in the narrative. The name Jonah is derived from the Hebrew word ‘yonah’ meaning “dove.” Although ‘yonah’ is generally defined as “dove,” its actual meaning remains uncertain based on its usage in other biblical books and other textual sources (e.g., Dead Sea Scrolls). Many commentators tend to treat “dove” as a symbol of Israel whose task was to convey the divine message to the Ninevites. Jonah’s father ‘amittay’ in Hebrew means “my truth,” which also led many to conjecture that Jonah’s mission was to speak the “truth” of YHWH to the Ninevites. This conclusion is based on the failure to distinguish the functionality between prose and poetry. In the book of Jonah, it is mostly composed in prose with only a small portion in poetry (2:2-9). In prose, not everything should be interpreted symbolically; some materials are to be taken literally – names of people for example.To numerous scholars, poetic elements are more original than prosaic materials in prophetic literature, which is simply based on the notion that the early Israelites were an illiterate community. Literacy was an uncommon practice in an agrarian setting. In this case, poetry would be the preference of preservation within this kind of community. This chauvinistic view of ancient Israel must be reconsidered because of the two crucial discovered inscriptional data: Gezer Calendar (discovered 1908 CE – translated by R. A. S. Macalister) and a pottery shard (discovered 2008 CE – deciphered by Gershon Galil), which support literary activities in ancient Israel before the time of the prophet Jonah.

Despite the absence of a specific identification of which tradition it refers to, the Dead Sea Scrolls (4Q541) hint at an additional possibility that “dove,” conveys a sorrowful message. This expression is also employed in Isaiah 38:14 – “Like a swallow or a crane I clamor, I moan like a dove.” As stated earlier, the chauvinistic view of ancient Israel being illiterate must be abandoned. Therefore, when dealing with prose, not all names, and places must be interpreted and understood symbolically. For modern readers, when encountering confliction in evidence, one’s interpretation of the book of Jonah must not be extracted exclusively from the symbolic meanings of ‘yonah’ and ‘amittay’, but on meticulous synchronic and diachronic analyses.

PARTS OF THE STORY OF JONAH DO CONTAIN HISTORICAL ELEMENTS, ALTHOUGH IT IS MORE PROBABLE THAT ITS CONSTRUCTION WAS DESIGNED TO REVEAL THE IMPORTANCE OF REPENTANCE & THE FATE OF NON-JEWS.

PURPOSE

Ironically, the book of Jonah is filled with irony, parody and exaggeration that are often overlooked by many interpreters. One other obvious hyperbolic element in the book is the repentance of animals together with the Ninevites, which influenced a number of scholars to challenge the historical level of the book. One other example is Jonah walking around the city of Nineveh in just three days, which is another figurative speech that is often taken literally. For some of these reasons, the book of Jonah has often been treated either as a didactic or a theological piece. An example is reflected in both Jewish and Christian traditions. In the pre-modern Jewish tradition, parts of the story of Jonah do contain historical elements, although it is more probable that its construction was designed to reveal the importance of repentance and the fate of non-Jews. In the Christian tradition, the prophet Jonah symbolizes resurrection from death after three days and nights in the fish’s belly, which is also reflected in the death and resurrection of Jesus in some of the synoptic gospels. Apparently, the story of Jonah is an important literature to both religious traditions.DATING

For reasons stated above, the book of Jonah contains elements that reveal a dual setting: ‘Sitz im Leben’ (Setting in Life) and a ‘Sitz im Literatur’ (Setting of its writing). From the small portion referencing the prophet Jonah in 2 Kings 14:25 who prophesied the expansion of King Jeroboam II’s kingdom, readers are left with the literary features of the book to determine its message and date of composition. Even more, 2 Kings 14:25 leaves the question open whether Jonah lived before or during Jeroboam II (787-748 BCE). Thus, dating the composition of the book remains disputed.Gezer Calender

Briefly, 2 Kings 14:25 places Jonah to the eighth-century BCE before or during the reign of King Jeroboam II, while the literary and linguistic features of the book call for a late composition. The book is written in two forms: prose and poetry, which also signals for a composited work. It is also composed of two types of Hebrew: classical biblical Hebrew and late biblical Hebrew. The classical biblical Hebrew is dated to the First Temple period, whereas the late biblical Hebrew dates to the Second Temple period. Furthermore, some scholars have also discovered Persian loan words in the book, whereby opting for post-exilic construction. The reference to Nineveh is one other element that encourages a later date of composition since Nineveh was later designated as the Assyrian capital by King Sennacherib c. 705 BCE. However, the ‘Sitz im Leben’ of early eighth-century in the book also gives the possibility of an earlier construction by the employment of classical biblical Hebrew in the book.CONTENT

2 Kings 14:25 indicates that Jonah is from Gath-Hepher - a small border town in ancient Israel (Galilee). Jonah was a well-known prophet during the reign of the Israelite King Jeroboam ben Joash of the northern kingdom of Israel (c. 786-746 BCE). According to the small reference in 2 Kings 14:25, Jonah prophesied King Jeroboam’s great success in restoring Israel’s borders from Lebo-Hamath (in modern Syria) down to the Sea of Arabah, which is at the northern tip of the 'Yam Suph' (Red Sea in the Septuagint and Englishversions). After Jonah received his call from God to journey to Nineveh (Chapter 1), the prophet fled down to the port of Yaffo (Joppa), which is situated at the southern boundaries of modern Tel Aviv. The actual location of Tarshish is also debated. Some have pointed to a place in Lebanon; others have argued for a location in Spain; and others have pointed out the correspondence of the name Tarshish to the Greek term tarsos, “oar.”After Jonah refused to obey God’s call to go to Nineveh, God hurled a great wind upon the sea, which resulted in Jonah being thrown into the deep waters and was swallowed by a dag, “fish” and was in the belly, ‘meeh’ in Hebrew (literally – intestines) for three days and three nights. Following Jonah’s prayer from the fish’s meehfor divine intervention (Chapter 2), God then spoke to the fish, “and it (the fish) spewed out Jonah upon dry land.”JONAH WAS A WELL-KNOWN PROPHET DURING THE REIGN OF THE ISRAELITE KING JEROBOAM BEN JOASH OF THE NORTHERN KINGDOM OF ISRAEL.

Jonah was called again (Chapter 3) and finally obeyed God’s command and went to preach repentance to the Ninevites. As a result, the King ordered repentance from his people, including their animals, and God was refrained from unleashing his wrath upon them. In the final chapter (Chapter 4) of the book, Nineveh is spared and Jonah is still depicted as dissatisfied with God’s decision to save the Ninevites. The book ends with a rhetorical question, which easily leads scholars to suggest that the book is designed to teach a theological message.

Jonah & the Whale

THEMES

Based on the historical and linguistic issues, the book of Jonah reflects four major themes:• Atonement versus Repentance

• Universalism versus Particularism

• Prophecy: Realization versus Compliance

• Compassion: Justice versus Mercy.

Such themes should be treated as critical foundational elements in determining a more probable context(s) of the book. It is probable that the message of Jonah is compatible to three different contexts: pre-exilic (eighth-century BCE); exilic (sixth-century BCE); and the post-exilic (539 BCE and after). In doing so, it is critical to construct a proper interpretation based on text and context. With the employment of both classical and late biblical Hebrew in the book, its construction probably began in the eighth-century BCE and was later re-applied to the exilic audience in Babylon and the post-exilic community in Jerusalem.

Since both Israel and Judah came under Assyrian hegemony in the ninth-century until Assyrian demise c. 612 BCE; under the Babylonians in the sixth-century; and the Persians in the late sixth-century to the fourth-century BCE, the composition of the book of Jonah reflects three functionalities. First, as a theodicy literature in the pre-exilic context (8th century BCE) to challenge YHWH’S fidelity; a didactic literature in the exilic period as a call for repentance from the exiled community; and as a resistant literature to counter the religious policy of Ezra and Nehemiah in the post-exilic (5th century BCE) concerning their intermarriage policy.

Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon

A THEODICY LITERATURE IN THE EIGHTH-CENTURY CONTEXT

With the employment of classical biblical Hebrew in the book of Jonah, it signals for an eighth-century composition. The period aligns with the Neo-Assyrian era (9th century to late seventh-century BCE), in which Israel and Judah were already subjugated under the Assyrian thumb. Retaliation to Assyrian hegemony during this period was never the best alternative, which they eventually did and consequently brought annihilation upon themselves. During the Neo-Assyrian period, Assyria was considered the ‘lion’ of the ancient Near East. Fortunately, at the outset of King Jeroboam II’s reign when the prophet Jonah was active, the Assyrian empire for a brief time experienced internal issues that enabled King Jeroboam to re-establish its economic stability and kingdom expansion. As Assyrian vassalages, Israel and Judah were also required to pay taxes to their overlord.This ongoing frustration in Israel is also reflected in the prophet Jonah’s refusal to bring YHWH’S plan of forgiveness to Nineveh because they will eventually repent. The refusal here not only depicts Jonah resisting forgiveness of their enemy, but also raises a question on YHWH’S fidelity and righteousness concerning their established covenant. By concluding the narrative with a set of rhetorical questions (4:9-11), it suggests in part that despite Israel’s attempts to uphold their part of the covenant, God changes his mind. A critical question to Jonah’s eighth-century audience would then be: can God keep his promises?

A DIDACTIC LITERATURE IN THE EXILIC CONTEXT

For a community exiled to a foreign land with high-hopes for divine intervention and restoration back to their homeland, repentance is key. If the Ninevites were pardoned from the wrath of YHWH because of their repentance, the exiled community must do likewise. Within this exilic-context, the character of Jonah resisting YHWH’S plan to forgive the Ninevites would only delay YHWH’S salvation plan for his people. Since forgiveness is a major theme in the book of Jonah, repentance signals their complete submission to YHWH’S extended compassion over all of his creation, including Nineveh. Limiting YHWH’S compassion within an Israelite boundary would only disrupt God’s universal control, which is a major theology in prophetic literature.From the exilic-context of the book of Jonah, there were undoubtedly theodicy issues raised amongst the exiled community in Babylon challenging YHWH’S fidelity in keeping them safe from external threats. Obviously, pride is another issue reflected through Jonah’s refusal to fulfill his duties as a prophet of YHWH. Overall, if the exiled-community would only repent of their mistakes, YHWH would immediately intervene just as he had done to Nineveh following their repentance. Thus, Nineveh’s immediate repentance functions as the main didactical element designed to convince the exiled community to repent of their infidelity.

A RESISTANT LITERATURE TO EZRA & NEHEMIAH’S RELIGIOUS POLICY

Readers should consider the construction of the final form of the book of Jonah during the post-exilic era in Jerusalem c. 5th century BCE based on the employment of the late biblical Hebrew in the book. For this reason, many scholars are convinced that in the aftermath of Judah’s restoration back into Jerusalem following the edict issued by King Cyrus of Persia c. 539 BCE of their release, there occurred intermarriage issues between Judeans and non-Jews in Jerusalem. One major example concerning this issue is reflected in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah who were also returnees from the Babylonian exile that helped re-establish the political and religious life in Jerusalem.For example, one of Ezra’s attempts was to re-establish pure Yahwism in Jerusalem as a way to prevent additional destruction upon Jerusalem by their enemies. As a result, Ezra and Nehemiah raise concerns concerning marriage relationships with non-Jews simply to faithfully reestablish their covenantal relationship with their God, YHWH. As generally misunderstood by numerous interpreters’, the call for exclusion of foreign wives in Ezra and Nehemiah were only limited on those who refuse to recant their foreign practices except those non-Jews who have agreed to the procedure of conversion. In the aftermath of the Babylonian experience, the need to re-establish their religious life and commitment to YHWH was necessary.

In this post-exilic context, the book of Jonah could be treated as a resistance literature against this religious policy inaugurated by Ezra and Nehemiah that foreign people are also part of YHWH’S creation. Therefore, Judah must purge their traditional beliefs concerning intermarriage relation with foreigners and to adopt a more inclusive ideology. A more inclusive ideology constitutes a more effective theology. If YHWH’s compassion was extended on non-Jews, it must also be reflected through Jerusalem.

CONCLUSION

With only four chapters in the book of Jonah, its message was undoubtedly an important piece throughout the biblical period based on its re-usage by the Israelite communities in the Babylonian exile and the post-exilic Jerusalem. Given the numerous major themes in the book and evidence of classical and late biblical Hebrew, the eighth-century message of Jonah took up a life of its own after the prophet’s lifetime by later tradents. The book of Jonah, therefore, was originally a theodicy literature in the eighth-century that was later readapted into a didactical literature in the sixth-century and finally into a resistant literature to counter the religious policy of Ezra and Nehemiah c. the fourth-century BCE.LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License