Never Seen: The Trace of a Jewish Spirit from Mesopotamia › Ancient Egyptian Burial › Ancient Egyptian Culture » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Never Seen: The Trace of a Jewish Spirit from Mesopotamia › Origins

- Ancient Egyptian Burial › Origins

- Ancient Egyptian Culture › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Never Seen: The Trace of a Jewish Spirit from Mesopotamia › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin

THE STORY BEGINS FROM A DEAD END

August 25, 2015 was a very hot day of summer but its omen was a very promising one! That day, I was with my friend, Mr. Hashim Hama Abdulla, director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum in Iraq, walking in the main hall of the Museum. So far, I had visited the museum innumerable times. I pointed towards something on the floor, which I had noticed on several occasions but I had never inquired about.

Gopala Jewish Tombstone

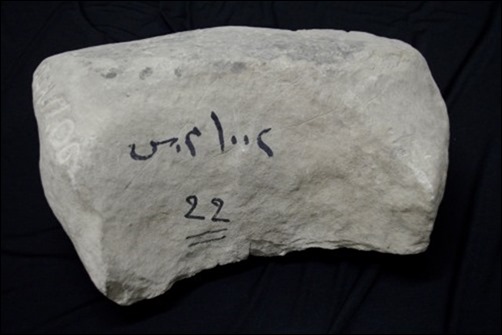

The upper surface of the so-called "Gopala Rock", inscribed with five lines, thought to be Aramaic. On the upper right margin, a single separate line of inscription also appear.

There was a rock, which was displayed on the floor directly, without any description. It was relatively dirty, strange, and irregular in shape and was inscribed with what appeared to be an ancient language. It was abutting the wall besides one of the large wood display cases. I'm sure, you can easily by-pass and miss it if you visit that hall. Nothing is striking or interesting about it, in addition to being placed in a non-attractive hidden space. “What is this? I forgot to ask you many times Kak(brother) Hashim?” These were the opening remarks of mine to Mr. Hashim. “It is a long story and we are waiting the results of the transliteration of these Aramaic or maybe Hebrew inscriptions”, Mr. Hashim replied. “It was found at the village near Bazian in late 1970s”. This was the last information I got from him that day.

UNDUSTING THE LENS

With his help, I got access to the archives of the museum to have a clearer idea about this “rock”. This is the summary of the “history” of the rock (coming from the archives of the museum and the information I got later on from Mr. Hashim):

1. While working in the field, Mr. Saman Mohammad Siddiq, an agricultural engineer found it in an apple farm, which lies in the village of Gopala (or Kopala) (Kurdish: ﮔوﭖاله), Bazian (or Baziyan; Kurdish: بازيان) Town (35°35'36.41"N; 45° 8'32.51"E). The village lies in the western part of the Governorate of Sulaymaniya, Iraqi Kurdistan.

2. He found it in the year 1979 CE and delivered it to the Sulaymaniyah Museum in early 1980s (at that time the Museum was closed to the public because of the Iraq-Iran War ).

3. The artefact is a rock, which has no particular shape and it is irregular in outline and borders.

4. Its maximum dimensions are 46 cm (length) x 39 cm (width) x 21 cm (height).

5. One surface (the upper one) is inscribed with five lines of Aramaic text. On one of the upper margins, there is one line of Aramaic inscription as well.

6. The most interesting point was that it was stored within the museum's repository, un-numbered, unregistered, and not displayed until December 25, 2001 CE. It was unnoticed by and unknown to the museum's staff and it was forgotten among the repository's contents. On that day, Mr. Saman himself paid a visit to the museum (the museum was closed in 1980 CE, reopened very shortly after the Iraq-Iran War in 1989 CE and was closed again, and finally re-opened in the year 2000 CE).Mr. Saman told Mr. Hashim about this rock and the story behind it. This was the event which brought it once again to life and revived its spirit.

7. The rock was registered on the day of December 25, 2001 and was given the registration number of “SM 1002” (Kurdish and Arabic: م. س. 2001). Mr. Hashim registered it and displayed it within the main hall the following day but without any description.

Once again, destiny strikes and imparts a long-lasting amnesia. The rock has been on display since then, but no one cares about it; a vagrant orphan lost in the arid desert, I describe it!

THE INSCRIPTION: AN ABOUT TURN

I contacted Mr. Hashim a few weeks ago (and that would be after almost two years), asking him about the rock. He gave me the contact details of Professor Narmeen Mohammed Amin Ali, a Kurdish archaeologist living in France. She was very cooperative! Dr. Narmeen said that a French archaeological team was doing excavations as well as studying Aramaic, Hebrew, and Syriac texts, scripts, and inscriptions in Kurdistan from 2011 to 2016. The team was headed by Professor Vincent Deroche, assisted by Professor Alain Desreumaux and herself. Professor Narmeen's main work was on the ruins of an ancient Christian church in Bazian.

THE SURPRISE WAS THAT PROFESSOR ALAIN COMMENTED THAT THIS IS NOT ARAMAIC, THIS IS HEBREW MOST LIKELY.

The team was visiting the Museum in mid-2013 and Mr. Hashim, by chance, told them that this rock was found in Bazian and he wondered whether they could find what it says. The surprise was that Professor Alain commented that this is not Aramaic, this is Hebrew most likely. Professor Alain took pictures of the rock, drew the inscriptions, and transliterated it over a period of one month. The article about the inscription will be published in the journal “Etudes mésopotamiennes - Mesopotamian Studies” in April 2018 and is titled “ une inscriptions hébraïque médiévale découverte dans Bet Garmaî (Kurdistan d'Irak) dans: Recherches au Kurdistan et en Mésopotamie du Nord) ”

. The article is in French and the English translation reads “A medieval Hebrew inscriptions discovered in Bet Garma (Kurdistan of Iraq), Kurdistan and Northern Mesopotamia Research”. This is exclusive information, so stay tuned until then!

. The article is in French and the English translation reads “A medieval Hebrew inscriptions discovered in Bet Garma (Kurdistan of Iraq), Kurdistan and Northern Mesopotamia Research”. This is exclusive information, so stay tuned until then!

Gopala Jewish Tombstone

Another side view of the Gopala Rock. The upper surface of the rock has not undergone any conservation work or cleaning;traces of modern paints remain.

WHAT DOES THIS ROCK REPRESENT?

This is a tombstone, which was commissioned by a man in memory of his deceased mother, “Siporah daughter of Dan”, who will rest in peace and be blessed in the Paradise of Eden. The inscribed date is the Seleucian year 1669 (which roughly corresponds to the year 1357/1358 CE). Professor Narmeen said that there is a similar tombstone dating to the same period, currently housed in the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

THE SO-CALLED ABRAHAMIC RELIGIONS (JUDAISM, CHRISTIANITY, & ISLAM) LIVED PEACEFULLY TOGETHER FOR MANY CENTURIES IN MESOPOTAMIA.

So, it was a tombstone, inscribed 700 years ago in the Hebrew language for a deceased Jewish woman. Bang bang! In my opinion, although the text is short, it is a remarkable surviving evidence confirming the existence of a multi-religious environment in Iraq. The so-called Abrahamic Religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) lived peacefully together for many centuries in Mesopotamia. The people in Bazian are currently Kurdish in ethnicity and Islamic in religion. The presence of this Jewish tombstone (undisturbed and unvandalized) in addition to the ruins of a Christian church within that same small place undoubtedly is a marker of a highly civilized, multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, and multi-linguistic society, which had melted and blended altogether, producing one solid and united body, living happily and friendly with each other for several generations. My parents once told me that many of their neighbours including their best childhood friends [in 1930s/1940s CE] were Jewish.Jewish people “were” one of the cornerstones of the Iraqi and Mesopotamian society. The demographic turmoil in the Middle East seems to continue, endlessly, for the benefit of whom?!

Lastly, no archaeological work has been done on the location where the tombstone was found. I think if we find the skeleton or at least some bones of that woman, we may, who knows, trace her offspring through DNA analysis! Where are her offspring now?

Detail, Gopala Jewish Tombstone

A zoomed-in image of the inscribed aspect (upper) of the Gopala Rock. Silver and bluish-green paints, which seem to be modern, cover some areas. This suggests that the rock was used by farmers for some purpose before it was given to the Sulaymaniya Museum!

Gopala Jewish Tombstone

The Goapal Rock has an irregular shape and margins.

Gopala Jewish Tombstone

The registration number of the Gopala Rock is SM 1002, which dates to December 25, 2001. It was registered after almost 20 years of storage in the museum's repository.

Gopala Jewish Tombstone

This is the under surface of Gopala Rock.

Gopala Jewish Tombstone

A behind-the-scenes image at the main hall of the Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraqi Kurdistan! From left to right: Siamand (my friend), me (Osama, the author and the cameraman), Khamis (an engineerworking in the Museum, and Hashim (Director of the Museum). I shot 212 images of the rock, using 3 lenses and a Nikon D610 camera.

I'm very happy to be the first one to share this very important discovery with the rest of the world through this article. I'm very grateful to Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah and Professor Narmeen Mohammed Amin Ali for their kind help and cooperation. A special gratitude goes to Professor Alain Jacque Desreumaux, who kindly agreed to share the tombstone's information with the public.

Everything that has existed, lingers in Eternity.

Agatha Christie.

Ancient Egyptian Burial › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

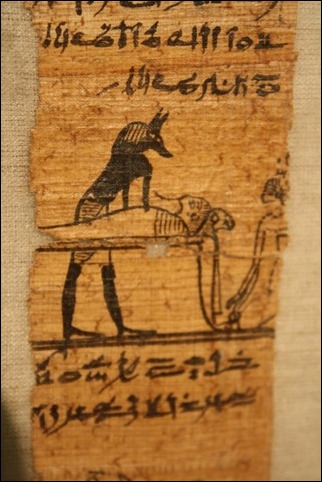

Egyptian burial is the common term for the ancient Egyptian funerary rituals concerning death and the soul's journey to the afterlife. Eternity, according to the historian Bunson, “was the common destination of each man, woman and child in Egypt ”

(87) but not `eternity' as in an afterlife above the clouds but, rather, an eternal Egypt which mirrored one's life on earth. The afterlife for the ancient Egyptians was The Field of Reeds which was a perfect reflection of the life one had lived on earth.Egyptian burial rites were practiced as early as 4000 BCE and reflect this vision of eternity. The earliest preserved body from a tomb is that of so-called `Ginger', discovered in Gebelein, Egypt, and dated to 3400 BCE. Burial rites changed over time between c. 4000 BCE and 30 BCE but the constant focus was on eternal life and the certainty of personal existence beyond death. This belief became well-known throughout the ancient world via cultural transmission through trade (notably by way of the Silk Road ) and came to influence other civilizations and religions. It is thought to have served as an inspiration for the Christian vision of eternal life and a major influence on burial practices in other cultures.

(87) but not `eternity' as in an afterlife above the clouds but, rather, an eternal Egypt which mirrored one's life on earth. The afterlife for the ancient Egyptians was The Field of Reeds which was a perfect reflection of the life one had lived on earth.Egyptian burial rites were practiced as early as 4000 BCE and reflect this vision of eternity. The earliest preserved body from a tomb is that of so-called `Ginger', discovered in Gebelein, Egypt, and dated to 3400 BCE. Burial rites changed over time between c. 4000 BCE and 30 BCE but the constant focus was on eternal life and the certainty of personal existence beyond death. This belief became well-known throughout the ancient world via cultural transmission through trade (notably by way of the Silk Road ) and came to influence other civilizations and religions. It is thought to have served as an inspiration for the Christian vision of eternal life and a major influence on burial practices in other cultures.

According to Herodotus (484-425/413 BCE), the Egyptian rites concerning burial were very dramatic in mourning the dead even though it was hoped that the deceased would find bliss in an eternal land beyond the grave. He writes:

As regards mourning and funerals, when a distinguished man dies, all the women of the household plaster their heads and faces with mud, then, leaving the body indoors, perambulate the town with the dead man's relatives, their dresses fastened with a girdle, and beat their bared breasts. The men too, for their part, follow the same procedure, wearing a girdle and beating themselves like the women. The ceremony over, they take the body to be mummified. (Nardo, 110)

Mummification was practiced in Egypt as early as 3500 BCE and is thought to have been suggested by the preservation of corpses buried in the arid sand. The Egyptian concept of the soul – which may have developed quite early – dictated that there needed to be a preserved body on the earth in order for the soul to have hope of an eternal life. The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts: the Khat was the physical body; the Ka one's double-form; the Ba a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens; Shuyet was the shadow self; Akh the immortal, transformed self, Sahuand Sechem aspects of the Akh ; Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil; Ren was one's secret name. The Khatneeded to exist in order for the Ka and Ba to recognize itself and so the body had to be preserved as intact as possible.

After a person had died, the family would bring the body of the deceased to the embalmers where the professionals “produce specimen models in wood, graded in quality. They ask which of the three is required, and the family of the dead, having agreed upon a price, leave the embalmers to their task” (Ikram, 53). There were three levels of quality and corresponding price in Egyptian burial and the professional embalmers would offer all three choices to the bereaved. According to Herodotus: “The best and most expensive kind is said to represent [ Osiris ], the next best is somewhat inferior and cheaper, while the third is cheapest of all” (Nardo, 110).

Egpytian Sarcophagus

These three choices in burial dictated the kind of coffin one would be buried in, the funerary rites available and, also, the treatment of the body. According to the historian Ikram,

The key ingredient in the mummification was natron, or netjry, divine salt. It is a mixture of sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate, sodium sulphate and sodium chloride that occurs naturally in Egypt, most commonly in the Wadi Natrun some sixty four kilometres northwest of Cairo. It has desiccating and defatting properties and was the preferred desiccant, although common salt was also used in more economical burials (55).

The body of the deceased, in the most expensive type of burial, was laid out on a table and the brain removed

via the nostrils with an iron hook, and what cannot be reached with the hook is washed out with drugs; next the flank is opened with a flint knife and the whole contents of the abdomen removed; the cavity is then thoroughly cleaned and washed out, firstly with palm wine and again with an infusion of ground spices. After that it is filled with pure myrrh, cassia, and every other aromatic substance, excepting frankincense, and sewn up again, after which the body is placed in natron, covered entirely over for seventy days – never longer. When this period is over, the body is washed and then wrapped from head to foot in linen cut into strips and smeared on the underside with gum, which is commonly used by the Egyptians instead of glue. In this condition the body is given back to the family who have a wooden case made, shaped like a human figure, into which it is put. (Ikram, 54, citing Herodotus).

The second most expensive burial differed from the first in that less care was given to the body.

No incision is made and the intestines are not removed, but oil of cedar is injected with a syringe into the body through the anus which is afterwards stopped up to prevent the liquid from escaping. The body is then cured in natron for the prescribed number of days, on the last of which the oil is drained off. The effect is so powerful that as it leaves the body it brings with it the viscera in a liquid state and, as the flesh has been dissolved by the natron, nothing of the body is left but the skin and bones. After this treatment, it is returned to the family without further attention. (Ikram, 54, citing Herodotus)

The third, and cheapest, method of embalming was “simply to wash out the intestines and keep the body for seventy days in natron” (Ikram, 54, citing Herodotus). The internal organs were removed in order to help preserve the corpse but, because it was believed the deceased would still need them, the viscera were placed in canopic jars to be sealed in the tomb. Only the heart was left inside the body as it was thought to contain the Ab aspect of the soul.

Even the poorest Egyptian was given some kind of ceremony as it was thought that, if the deceased were not properly buried, the soul would return in the form of a ghost to haunt the living. As mummification could be very expensive, the poor gave their used clothing to the embalmers to be used in wrapping the corpse. This gave rise to the phrase “The Linen of Yesterday” alluding to death. “The poor could not afford new linens, and so wrapped their beloved corpses in those of `yesterday'” (Bunson, 146). In time, the phrase came to be applied to anyone who had died and was employed by the Kites of Nephthys(the professional female mourners at funerals). “The deceased is addressed by these mourners as one who dressed in fine linen but now sleeps in the `linen of yesterday'. That image alluded to the fact that life upon the earth became `yesterday' to the dead” (Bunson, 146). The linen bandages were also known as The Tresses of Nephthys after that goddess, the twin sister of Isis, became associated with death and the afterlife. The poor were buried in simple graves with those artifacts they had enjoyed in life or whatever objects the family could afford to part with.

Sarcophagus of Kha (Detail)

Every grave contained some sort of provision for the afterlife. Tombs in Egypt were originally simple graves dug into the earth which then developed into the rectangular mastabas, more ornate graves built of mud brick. Mastabas eventually advanced in form to become the structures known as `step pyramids ' and those then became `true pyramids'. These tombs became increasingly important as Egyptian civilization advanced in that they would be the eternal resting place of the Khat and that physical form needed to be protected from grave robbers and the elements. The coffin, or sarcophagus, was also securely constructed for the purposes of both symbolic and practical protection of the corpse. The line of hieroglyphics which run vertically down the back of a sarcophagus represent the backbone of the deceased and was thought to provide strength to the mummy in rising to eat and drink.

Provisioning the tomb, of course, relied upon one's personal wealth and, among the artifacts included were Shabti Dolls. In life, the Egyptians were called upon to donate a certain amount of their time every year to public building projects. If one were ill, or could not afford the time, one could send a replacement worker. One could only do this once in a year or else face punishment for avoidance of civic duty. In death, it was thought, people would still have to perform this same sort of service (as the afterlife was simply a continuation of the earthly one) and so Shabti Dolls were placed in the tomb to serve as one's replacement worker when called upon by the god Osiris for service. The more Shabti Dolls found in a tomb, the greater the wealth of the one buried there. As on earth, each Shabti could only be used once as a replacement and so more dolls were to be desired than less and this demand created an industry dedicated to their creation.

Once the corpse had been mummified and the tomb prepared, the funeral was held in which the life of the deceased was honored and the loss mourned. Even if the deceased had been popular, with no shortage of mourners, the funeral procession and burial was accompanied by Kites of Nephthys (always women) who were paid to lament loudly throughout the proceedings. They sang The Lamentation of Isis and Nephthys, which originated in the myth of the two sisters weeping over the death of Osiris, and were supposed to inspire others at the funeral to a show of emotion. As in other ancient cultures, remembrance of the dead ensured their continued existence in the afterlife and a great showing of grief at a funeral was thought to have echoes in the Hall of Truth (also known as The Hall of Osiris) where the soul of the departed was heading.

From the Old Kingdom Period on, the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony was performed either before the funeral procession or just prior to placing the mummy in the tomb. This ceremony again underscores the importance of the physical body in that it was conducted in order to reanimate the corpse for continued use by the soul. A priest would recite spells as he used a ceremonial blade to touch the mouth of the corpse (so it could again breathe, eat, and drink) and the arms and legs so it could move about in the tomb. Once the body was laid to rest and the tomb sealed, other spells and prayers, such as The Litany of Osiris (or, in the case of a pharaoh, the spells known as The Pyramid Texts ) were recited and the deceased was then left to begin the journey to the afterlife.

Ancient Egyptian Culture › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Ancient Egyptian culture flourished between c. 5500 BCE with the rise of technology (as evidenced in the glass-work of faience ) and 30 BCE with the death of Cleopatra VII, the last Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt. It is famous today for the great monuments which celebrated the triumphs of the rulers and honored the gods of the land. The culture is often misunderstood as having been obsessed with death but, had this been so, it is unlikely it would have made the significant impression it did on other ancient cultures such as Greece and Rome. The Egyptian culture was, in fact, life affirming, as the scholar Salima Ikram writes:

Judging by the numbers of tombs and mummies that the ancient Egyptians left behind, one can be forgiven for thinking that they were obsessed by death. However, this is not so. The Egyptians were obsessed by life and its continuation rather than by a morbid fascination with death. The tombs, mortuary temples and mummies that they produced were a celebration of life and a means of continuing it for eternity…For the Egyptians, as for other cultures, death was part of the journey of life, with death marking a transition or transformation after which life continued in another form, the spiritual rather than the corporeal. (ix).

This passion for life imbued in the ancient Egyptians a great love for their land as it was thought that there could be no better place on earth in which to enjoy existence. While the lower classes in Egypt, as elsewhere, subsisted on much less than the more affluent, they still seem to have appreciated life in the same way as the wealthier citizens. This is exemplified in the concept of gratitude and the ritual known as The Five Gifts of Hathor in which the poor labourers were encouraged to regard the fingers of their left hand (the hand they reached with daily to harvest field crops) and to consider the five things they were most grateful for in their lives. Ingratitude was considered a `gateway sin' as it led to all other types of negative thinking and resultant behaviour. Once one felt ungrateful, it was observed, one then was apt to indulge oneself further in bad behaviour.The Cult of Hathor was very popular in Egypt, among all classes, and epitomizes the prime importance of gratitude in Egyptian culture.

RELIGION IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Religion was an integral part of the daily life of every Egyptian. As with the people of Mesopotamia, the Egyptians considered themselves co-labourers with the gods but with an important distinction: whereas the Mesopotamian peoples believed they needed to work with their gods to prevent the recurrence of the original state of chaos, the Egyptians understood their gods to have already completed that purpose and a human's duty was to celebrate that fact and give thanks for it. So-called ` Egyptian mythology ' was, in ancient times, as valid a belief structure as any accepted religion in the modern day.

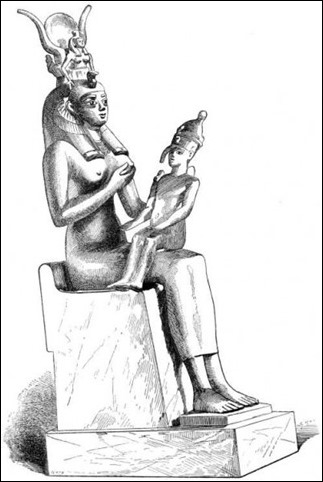

Egyptian religion taught the people that, in the beginning, there was nothing but chaotic swirling waters out of which rose a small hill known as the Ben-Ben. Atop this hill stood the great god Atum who spoke creation into being by drawing on the power of Heka, the god of magic. Heka was thought to pre-date creation and was the energy which allowed the gods to perform their duties. Magic informed the entire civilization and Heka was the source of this creative, sustaining, eternal power.

In another version of the myth, Atum creates the world by first fashioning Ptah, the creator god who then does the actual work.Another variant on this story is that Ptah first appeared and created Atum. Another, more elaborate, version of the creation story has Atum mating with his shadow to create Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture) who then go on to give birth to the world and the other gods.

From this original act of creative energy came all of the known world and the universe. It was understood that human beings were an important aspect of the creation of the gods and that each human soul was as eternal as that of the deities they revered. Death was not an end to life but a re-joining of the individual soul with the eternal realm from which it had come.

The Egyptian concept of the soul regarded it as being comprised of nine parts: the Khat was the physical body; the Ka one's double-form; the Ba a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens; Shuyet was the shadow self; Akh the immortal, transformed self, Sahu and Sechem aspects of the Akh ; Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil;Ren was one's secret name.

An individual's name was considered of such importance that an Egyptian's true name was kept secret throughout life and one was known by a nickname. Knowledge of a person's true name gave one magical powers over that individual and this is among the reasons why the rulers of Egypt took another name upon ascending the throne; it was not only to link oneself symbolically to another successful pharaoh but also a form of protection to ensure one's safety and help guarantee a trouble-free journey to eternity when one's life on earth was completed. According to the historian Margaret Bunson:

Eternity was an endless period of existence that was not to be feared by any Egyptian. The term `Going to One's Ka' (astral being) was used in each age to express dying. The hieroglyph for a corpse was translated as `participating in eternal life'. The tomb was the `Mansion of Eternity' and the dead was an Akh, a transformed spirit. (86).

The famous Egyptian mummy (whose name comes from the Persian and Arabic words for `wax' and `bitumen', muum and mumia ) was created to preserve the individual's physical body ( Khat ) without which the soul could not achieve immortality.As the Khat and the Ka were created at the same time, the Ka would be unable to journey to The Field of Reeds if it lacked the physical component on earth. The gods who had fashioned the soul and created the world consistently watched over the people of Egypt and heard and responded to, their petitions. A famous example of this is when Ramesses II was surrounded by his enemies at the Battle of Kadesh (1274 BCE) and, calling upon the god Amun for aid, found the strength to fight his way through to safety. There are many far less dramatic examples, however, recorded on temple walls, stele, and on papyrus fragments.

CULTURAL ADVANCES & DAILY LIFE

Papyrus (from which comes the English word `paper') was only one of the technological advances of the ancient Egyptian culture. The Egyptians were also responsible for developing the ramp and lever and geometry for purposes of construction, advances in mathematics and astronomy (also used in construction as exemplified in the positions and locations of the pyramids and certain temples, such as Abu Simbel ), improvements in irrigation and agriculture (perhaps learned from the Mesopotamians), ship building and aerodynamics (possibly introduced by the Phoenicians ) the wheel (brought to Egypt by the Hyksos ) and medicine.

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (c. 1800 BCE) is an early treatise on women's health issues and contraception and the Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE) is the oldest work on surgical techniques. Dentistry was widely practised and the Egyptians are credited with inventing toothpaste, toothbrushes, the toothpick, and even breath mints. They created the sport of bowling and improved upon the brewing of beer as first practised in Mesopotamia. The Egyptians did not, however, invent beer. This popular fiction of Egyptians as the first brewers stems from the fact that Egyptian beer more closely resembled modern-day beer than that of the Mesopotamians.

Glass working, metallurgy in both bronze and gold, and furniture were other advancements of Egyptian culture and their art and architecture are famous world-wide for precision and beauty. Personal hygiene and appearance was valued highly and the Egyptians bathed regularly, scented themselves with perfume and incense, and created cosmetics used by both men and women. The practice of shaving was invented by the Egyptians as was the wig and the hairbrush.

By 1600 BCE the water clock was in use in Egypt, as was the calendar. Some have even suggested that they understood the principle of electricity as evidenced in the famous Dendera Light engraving on the wall of the Hathor Temple at Dendera. The images on the wall have been interpreted by some to represent a light bulb and figures attaching said bulb to an energy source. This interpretation, however, has been largely discredited by the academic community.

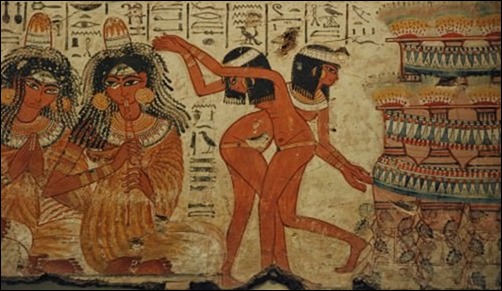

Ancient Egyptian Music and Dancing

In daily life, the Egyptians seem little different from other ancient cultures. Like the people of Mesopotamia, India, China, and Greece, they lived, mostly, in modest homes, raised families, and enjoyed their leisure time. A significant difference between Egyptian culture and that of other lands, however, was that the Egyptians believed the land was intimately tied to their personal salvation and they had a deep fear of dying beyond the borders of Egypt. Those who served their country in the army, or those who travelled for their living, made provision for their bodies to be returned to Egypt should they be killed. It was thought that the fertile, dark earth of the Nile River Delta was the only area sanctified by the gods for the re-birth of the soul in the afterlife and to be buried anywhere else was to be condemned to non-existence.

Because of this devotion to the homeland, Egyptians were not great world-travellers and there is no `Egyptian Herodotus ' to leave behind impressions of the ancient world beyond Egyptian borders. Even in negotiations and treaties with other countries, Egyptian preference for remaining in Egypt was dominant. The historian Nardo writes,

Though Amenophis III had joyfully added two Mitanni princesses to his harem, he refused to send an Egyptian princess to the sovereign of Mitanni, because, `from time immemorial a royal daughter from Egypt has been given to no one.' This is not only an expression of the feeling of superiority of the Egyptians over the foreigners but at the same time and indication of the solicitude accorded female relatives, who could not be inconvenienced by living among `barbarians'. (31)

Further, within the confines of the country people did not travel far from their places of birth and most, except for times of war, famine or other upheaval, lived their lives and died in the same locale. As it was believed that one's afterlife would be a continuation of one's present (only better in that there was no sickness, disappointment or, of course, death), the place in which one spent one's life would constitute one's eternal landscape. The yard and tree and stream one saw every day outside one's window would be replicated in the afterlife exactly. This being so, Egyptians were encouraged to rejoice in and deeply appreciate their immediate surroundings and to live gratefully within their means. The concept of ma'at (harmony and balance) governed Egyptian culture and, whether of upper or lower class, Egyptians endeavoured to live in peace with their surroundings and with each other.

CLASS DISTINCTIONS IN EGYPTIAN CULTURE

Among the lower classes, homes were built of mud bricks baked in the sun. The more affluent a citizen, the thicker the home;wealthier people had homes constructed of a double layer, or more, of brick while poorer people's houses were only one brick wide. Wood was scarce and was only used for doorways and window sills (again, in wealthier homes) and the roof was considered another room in the house where gatherings were routinely held as the interior of the homes were often dimly lighted.

Clothing was simple linen, un-dyed, with the men wearing a knee-length skirt (or loincloth) and the women in light, ankle-length dresses or robes which concealed or exposed their breasts depending on the fashion at a particular time. It would seem that a woman's level of undress, however, was indicative of her social status throughout much of Egyptian history. Dancing girls, female musicians, and servants and slaves are routinely shown as naked or nearly naked while a lady of the house is fully clothed, even during those times when exposed breasts were a fashion statement.

Even so, women were free to dress as they pleased and there was never a prohibition, at any time in Egyptian history, on female fashion. A woman's exposed breasts were considered a natural, normal, fashion choice and was in no way deemed immodest or provocative. It was understood that the goddess Isis had given equal rights to both men and women and, therefore, men had no right to dictate how a woman, even one's own wife, should attire herself. Children wore little or no clothing until puberty.

Isis Nursing Horus

Marriages were not arranged among the lower classes and there seems to have been no formal marriage ceremony. A man would carry gifts to the house of his intended bride and, if the gifts were accepted, she would take up residence with him. The average age of a bride was 13 and that of a groom 18-21. A contract would be drawn up portioning a man's assets to his wife and children and this allotment could not be rescinded except on grounds of adultery (defined as sex with a married woman, not a married man). Egyptian women could own land, homes, run businesses, and preside over temples and could even be pharaohs (as in the example of Queen Hatshepsut, 1479-1458 BCE) or, earlier, Queen Sobeknofru, c. 1767-1759 BCE).

The historian Thompson writes, "Egypt treated its women better than any of the other major civilizations of the ancient world. The Egyptians believed that joy and happiness were legitimate goals of life and regarded home and family as the major source of delight.” Because of this belief, women enjoyed a higher prestige in Egypt than in any other culture of the ancient world.

While the man was considered the head of the house, the woman was head of the home. She raised the children of both sexes until, at the age or four or five, boys were taken under the care and tutelage of their fathers to learn their profession (or attend school if the father's profession was that of a scribe, priest, or doctor). Girls remained under the care of their mothers, learning how to run a household, until they were married. Women could also be scribes, priests, or doctors but this was unusual because education was expensive and tradition held that the son should follow the father's profession, not the daughter. Marriage was the common state of Egyptians after puberty and a single man or woman was considered abnormal.

The higher classes, or nobility, lived in more ornate homes with greater material wealth but seem to have followed the same precepts as those lower on the social hierarchy. All Egyptians enjoyed playing games, such as the game of Senet (a board game popular since the Pre-Dynastic Period, c. 5500-3150 BCE) but only those of means could afford a quality playing board.This did not seem to stop poorer people from playing the game, however; they merely played with a less ornate set.

Watching wrestling matches and races and engaging in other sporting events, such as hunting, archery, and sailing, were popular among the nobility and upper class but, again, were enjoyed by all Egyptians in as much as they could be afforded (save for large animal hunting which was the sole provenance of the ruler and those he designated). Feasting at banquets was a leisure activity only of the upper class although the lower classes were able to enjoy themselves in a similar (though less lavish) way at the many religious festivals held throughout the year.

SPORTS & LEISURE

Swimming and rowing were extremely popular among all classes. The Roman writer Seneca observed common Egyptians at sport the Nile River and described the scene:

The people embark on small boats, two to a boat, and one rows while the other bails out water. Then they are violently tossed about in the raging rapids. At length, they reach the narrowest channels…and, swept along by the whole force of the river, they control the rushing boat by hand and plunge head downward to the great terror of the onlookers. You would believe sorrowfully that by now they were drowned and overwhelmed by such a mass of water when, far from the place where they fell, they shoot out as from a catapult, still sailing, and the subsiding wave does not submerge them, but carries them on to smooth waters. (Nardo, 18)

Swimming was an important part of Egyptian culture and children were taught to swim when very young. Water sports played a significant role in Egyptian entertainment as the Nile River was such a major aspect of their daily lives. The sport of water-jousting, in which two small boats, each with one or two rowers and one jouster, fought each other, seems to have been very popular. The rower (or rowers) in the boat sought to strategically maneuver while the fighter tried to knock his opponent out of the craft. They also enjoyed games having nothing to do with the river, however, which were similar to modern-day games of catch and handball.

Egyptian Hunting in the Marshes

Gardens and simple home adornments were highly prized by the Egyptians. A home garden was important for sustenance but also provided pleasure in tending to one's own crop. The labourers in the fields never worked their own crop and so their individual garden was a place of pride in producing something of their own, grown from their own soil. This soil, again, would be their eternal home after they left their bodies and so was greatly valued. A tomb inscription from 1400 BCE reads, “May Iwalk every day on the banks of the water, may my soul rest on the branches of the trees which I planted, may I refresh myself under the shadow of my sycamore” in referencing the eternal aspect of the daily surroundings of every Egyptian. After death, one would still enjoy one's own particular sycamore tree, one's own daily walk by the water, in an eternal land of peace granted to those of Egypt by the gods they gratefully revered.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License