Ancient Greek Inventions » Theogony » Pilgrimage in the Byzantine Empire » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions » Contents

- Ancient Greek Inventions » Origins

- Theogony » Origins

- Pilgrimage in the Byzantine Empire » Origins

Ancient civilizations » Historical places, and their characters

Ancient Greek Inventions » Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

The ancient Greeks are often credited with building the foundations upon which all western cultures are built, and this impressive accolade stems from their innovative contributions to a wide range of human activities, from sports to medicine, architecture to democracy. Like any other culture before or since, the Greeks learnt from the past, adapted good ideas they came across when they met other cultures, and developed their own brand new ideas. Here are just some of the ways the ancient Greeks have uniquely contributed to world culture, many of which are still going strong today.Theatre of Delphi

COLUMNS & STADIUMS

Just about any city in the western world today has examples of Greek architecture on its streets, especially in its biggest and most important public buildings. Perhaps the most common features invented by the Greeks still around today are the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns which hold up roofs and adorn facades in theatres, courthouses, and government buildings across the globe. The Greeks used these architectural orders primarily for their temples, many of which are still standing today despite earthquake, fire, and cannon shots - the Parthenon, completed in 432 BCE, is the biggest and most famous example. The collonaded stoa to protect walkers from the elements, the gymnasium with baths and training fields, the semi-circular theatre with rising rows of seats, and the banked rectangular stadium for sports, are just some of the features of Greek architecture that any modern city would seem strange indeed without.HUMAN SCULPTURE IN ART

Greek innovations in art are perhaps seen most clearly in figure sculpture. Previous and contemporary ancient cultures had represented the human figure in a simple standing and rather static pose so that the people represented often looked as lifeless as the stone from which they were carved. Greek sculptors, though, inched towards a more dynamic result. In the Archaic period the stance becomes a little more relaxed, the elbows a little more bent and both tension and movement are thus suggested. By the Classical period statues have broken away from all convention and become sensuous, writhing figures that seem about to jump off the plinth. Greek sculpture and art, in general, began a preoccupation with proportion, poise, and the idealised perfection of the human body that was continued by the Romans and would go on to influence Renaissance art and many sculptors thereafter.Bronze Greek Athlete

DEMOCRACY & JURY SYSTEM IN LAW

One of the big ideas of the Greeks was that ordinary citizens should have an equal say in not just who governed them but also how they governed. Even more importantly, that input was to be direct and in person. Consequently, in some Greek city-states, 5th-4th-century BCE Athens being the most famous example, citizens (defined then as free males over 18) could actively participate in government by attending the public assembly to speak, listen, and vote on issues of the day. The Athenian assembly had a physical capacity of 6,000 people, and one can imagine that on many days only the most enthusiastic of the demos(people) would have turned up but when the big issues were on the table the place was packed. A simple majority vote won the day and was calculated by a show of hands.On top of this already startling idea of direct democracy, all citizens could, and indeed were expected to, participate in government by serving as magistrates, jurors, and any official post they were capable of holding. Further, anyone seen to abuse their public position, which was usually only for a temporary term anyway, could be kicked out of the city in the secret vote known as ostracism.ALL ATHENIAN CITIZENS COULD, & INDEED WERE EXPECTED TO, PARTICIPATE IN GOVERNMENT.

Part and parcel of the democratic apparatus was the jury system - the idea that those accused of crimes were judged by their peers. Nowadays a jury system usually consists of twelve people but in ancient Athens, it was the entire assembly and each member was picked at random using a machine known as the kleroterion. This device randomly dispensed tokens and if you got a black one then you had to do jury service that day. The system made sure that nobody knew who would be the jurors that day and so could not bribe anyone to influence their decision. In a carefully considered system that thought of everything, jurors were even compensated their expenses.

Kleroteria

ENGINEERING & MECHANICAL DEVICES

The Romans might have grabbed all the accolades for best ancient engineers but the Greeks did have their own mechanical devices which allowed them to move massive chunks of marble using the block and tackle, winch, and crane for their huge temples and city walls. They created tunnels in mountains such as the one-kilometre tunnel in Samos, built in the 6th century BCE. Aqueducts was another area the Greeks were not lacking in imagination and design, and so they shifted water to where it was most needed; watermills, too, were used to harness nature’s power.Perhaps the area of greatest innovation, though, was in the small-scale production of mechanical devices. The legendary figure of Daedalus, architect of King Minos’ labyrinth, was credited with creating life-like automata and all manner of mechanical wonders. Daedalus may never have existed, but the legends around him indicate a Greek love of all-things magically mechanical. Handy Greek devices included the portable sundial of Parmenion made from rings (c. 400-330 BCE), the water alarm clock credited to Plato (c. 428- c. 424 BCE) which used water dropping through various clay vessels which eventually caused air pressure to sound off a whistle-hole, Timosthenes’ 3rd-century BCE anemoscope to measure the wind direction, and the 3rd-century BCE hydraulic organ of Ktesibios. Then there was the odometer which measured land distances using a wheel and cogs, the suspended battering ram to provide more punch when breaking down enemy gates, and the flamethrower with a bellows at one end and a cauldron of flammable liquid at the other which the Boeotians used to such good effect in the Peloponnesian War.

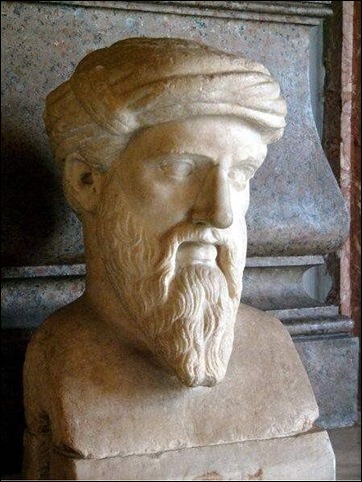

Bust of Pythagoras

MATHEMATICAL REASONING & GEOMETRY

Other cultures had shown a keen interest in mathematics but perhaps the Greeks' unique contribution to the field was the effort to apply the subject to practical and everyday problems. Indeed, for the Greeks, the subject of maths was inseparable from philosophy, geometry, astronomy, and science in general. The great achievement in the field was the emphasis on deductive reasoning, that is forming a logically certain conclusion based on the reasoning of a chain of statements. Thales of Miletus, for example, crunched his numbers to accurately predict the solar eclipse of May 28, 585 BCE, and he is credited with calculating the height of the pyramids based on the length of their shadow. Undoubtedly, the most famous Greek mathematician is Pythagoras (c. 571- c. 497 BCE) with his geometric theorem which still carries his name - that in a right triangle the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the squares of the short sides added together.DIET, LIFESTYLE & CONSTITUTION WERE ALL RECOGNISED AS CONTRIBUTING FACTORS TO DISEASE.

MEDICINE

The early Greeks considered illness a divine punishment, but from the 5th century BCE a more scientific approach was taken, and both diagnosis and cure became a lot more useful to the patient. Symptoms and cures were carefully observed, tested, and recorded. Diet, lifestyle, and constitution were all recognised as contributing factors to disease. Treatises were written, most famously by the 5th-4th-century BCE founder of western medicine Hippocrates. A better understanding of the human body was achieved. Observation of badly wounded soldiers showed, for example, the differences between arteries and veins, although dissection of humans would only come in Hellenistic times. Medicines were perfected using herbs; celery was known to have anti-inflammatory properties, egg-white was good for sealing wounds, while opium could provide pain relief or work as an anaesthetic. While it is true that surgery was avoided and there were still many wacky explanations floating about, not to mention a still strong connection to religion, Greek doctors had begun the long road of medical enquiry which is still being pursued to this day.OLYMPIC GAMES

Sporting competitions had already been seen in the Minoan and Mycenaean civilisations of the Bronze Age Aegean, but it was in Archaic Greece that a sporting event would be born which became so popular and so important that it was even used as a reference for the calendar. The first Olympic Games were held in mid-July in 776 BCE at Olympia in honour of the Greek god Zeus. Every four years, thereafter, athletes and spectators gathered from across the Greek world to perform great sporting deeds and win favour with the gods. The last ancient Olympics would be in 393 CE, after an incredible run of 293 consecutive Olympiads.Greek Wrestlers

There was a widely respected truce in all conflicts to allow participants and spectators to travel in safety to Olympia. At first, there was only one event, the stadion - a foot race of one circuit of the stadium (about 192 m) in which some 45,000 all-male spectators gathered to cheer on their favourite. The event got bigger and bigger over the years with longer footraces added to the repertoire and new events held such as the discus, boxing, pentathlon, wrestling, chariot racing, and even competitions for trumpeters and heralds.Specially trained judges supervised the events and dished out fines to anyone breaking the rules. The winners received a crown of olive leaves, instant glory, perhaps some cash put up by their hometown, and even immortality, especially for the winners of the stadion whose name was given to that particular games. The Olympic Games were revived in 1896 CE and, of course, are still going strong, even if they have another thousand years to go to match the longevity of their ancient version.

PHILOSOPHY

The great Greek thinkers attacked all of the questions that have ever puzzled humanity. Figures such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle in the 5th and 4th century BCE endlessly questioned and debated where we come from, how we have developed, where we are going to, and should we even be bothering to think about it all in the first place. The Greeks had a branch of philosophy to suit all tastes from the grin-and-bear-it Stoics to the live for the minute, live simply and live happily Epicureans. In the 6th century BCE, Anaximanderprovides the first surviving textual reference of western philosophy and he considered that “the boundless” was responsible for the elements - so we have still not made very much progress since that statement.Aristotle

Collectively, all of these thinkers illustrate one common factor: the Greek’s desire to answer all questions no matter their difficulty. Neither were Greek philosophers limited to theoretical answers as many were also physicists, biologists, astronomers, and mathematicians. Perhaps the Greek approach and contribution to philosophy, in general, is best summarised by Parmenides and his belief that as the senses cannot be trusted, we must apply our minds to cut through the haze of superstition and myth and use whatever tools at our disposal to find the answers we are looking for. We may not have found many more solutions since the Greek thinkers provided theirs but their unbounded spirit of enquiry is perhaps their greatest and most lasting contribution to western thought.SCIENCE & ASTRONOMY

As in the field of philosophy, Greek scientists were keen to find solutions which explained the world around them. All manner of theories were proposed, tested and debated, even rejected by many. That the earth was a globe, that the world revolved around the sun and not vice versa, that the Milky Way was composed of stars, that humanity had evolved from other animals were just some of the ideas the Greek thinkers floated around for contemplation. Archimedes (287-212 BCE) in his bath discovered displacement and cried “Eureka!”, Aristotle (384-322 BCE) developed logic and classified the natural world, and Eratosthenes (276-195 BCE) calculated the circumference of the globe from the shadows cast by objects at two different latitudes. Once again, though, it was not the individual discoveries that were important, it was the general belief that all things can be explained by deductive reasoning and the careful examination of available evidence.Greek Tragedy Mask

THEATRE

It was the ancient Athenians who invented theatre performance in the 6th century BCE. Perhaps originating from either the recital of epic poems set to music or rituals involving music, dance and masks to honour the god of wine Dionysos, Greek tragedies were first performed at religious festivals, and from these came the spin-off genre of Greek comedyplays. Performed by professional actors in purpose-built open-air theatres, Greek plays were popular and free. Not only a fleeting pastime performance, many of the classic plays were studied as a staple part of the education curriculum.In the tragedies, people were engrossed in the twists presented on familiar tales from Greek mythology and the no-win situations for the heroic but doomed characters. The cast might have been very limited but the chorus group added some musical oomph to the proceedings. When comedy came along, there was fun in seeing familiar politicians, philosophers, and foreigners lampooned, and playwrights became ever more ambitious in their presentations, with all-singing, all-dancing chorus lines, outlandish costumes, and special effects such as actors dangling from hidden wires above the beautifully crafted sets. As in many other fields, the entertainment industry of today owes a great debt to the ancient Greeks.

Theogony » Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Donald L. Wasson

The Theogony is an 8th-century BCE didactic and instructional poem, credited to the Greek poet Hesiod. The Theogony was, at first, not actually written down, rather, it was part of a rich oral tradition which only achieved written form decades later. The Theogony traces the history of the world from its creation through the battle between the Olympians and the Titans to the ascension of Zeus as the absolute ruler of all of the Olympian gods. With the rise of Zeus to supremacy and the birth of his many children, the poem ends and does not address the continued struggles between mankind and the gods. Much of what is known today concerning early Greek mythology comes from Hesiod's work and that other great Greek poet Homer. Collectively, their works would serve as a major influence on later Greek literature and drama, and Roman mythology, especially through the epic Metamorphoses by Ovid.

AUTHORSHIP

The Theogony (from the Greek theogonia, meaning "generations of the gods") is an epic poem of 1,022 hexameter lines which describes the birth of the gods in the Greek pantheon. It is thought to have been composed c. 700 BCE (give or take a generation either side of that date). Little is known of Hesiod’s life. His father emigrated from Cyme in Asia Minor and settled in Boeotia, a small state in central Greece. It is assumed that the poet was a farmer; a fact garnered from the early verses of the Theogony. He may also have been a rhapsodist, a reciter of poetry, where he learned the technique and vocabulary of heroic songs.Although there are some who question whether or not Hesiod actually wrote the Theogony, most classicists believe he did. However, parts of the work may have been added by later poets and there is a definite similarity in some aspects to earlier Mesopotamian literature. The historian Dorothea Wender believes that the Theogony was an earlier work than Works and Days, the other work attributed to Hesiod. She considers the latter to be a better work, and while the Theogony seems to be unpolished, the author could have had difficulty with written composition.

Wender criticizes Hesiod for not discussing the dethroning of Kronos and his endless mention of "colourless deities." Also, Hesiod’s Zeus is too invincible. There is no suspense. "Homer gets more excitement out of a footrace than Hesiod does out of a full-scale war in heaven" (18). However, to Wender, the poem still has historical interest. Certainly, the Theogony was influential; the historian Norman Cantor in his Antiquity wrote that the Greeks adopted Homer and Hesiod’s notion of the gods andHESIOD WAS INFLUENTIAL ON CLASSICAL GREEK LITERATURE & PHILOSOPHY, HIS PROMETHEUS STORY, FOR EXAMPLE, INSPIRING SUCH PLAYWRIGHTS AS AESCHYLUS.

a distinctive Greek religion was developed. This religion was always complex and never consistent in all its details; still, its view of man and the world lies at the center of Greek culture. (123)Hesiod was influential on Classical Greek literature and philosophy, his Prometheus story, for example, inspiring such playwrights as Aeschylus (c. 525 - c. 456 BCE). His poetic style was much imitated, particularly in Hellenistic times and in Roman times - both the Republic and Imperial Rome - when Hesiod's works continued to be recited and set to music. The great Roman writer Ovid (43 BCE - 17 CE) would use many of the themes of the Theogony in his Metamorphoses.

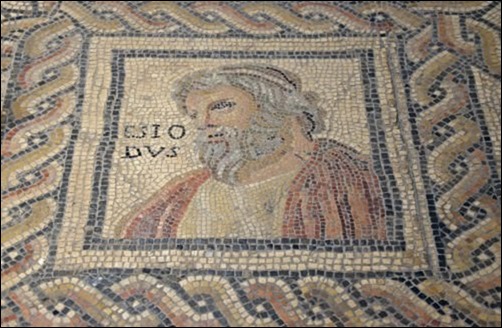

PORTRAIT OF HESIOD

HOMER VS HESIOD

In the introduction to her translation of the Theogony, Wender compared the gods of Homer to those of Hesiod. Although Homer’s Olympians may not have been admirable ethically - they lied, cheated, and stole - they were still civilized. Homer erased their sins with no mention of any "primitive behavior." However, Hesiod made no effort to "whitewash the mythological past in terms of modern standards with one exception. The exception is Zeus, the hero of the poem, whose omniscience, power and justice are stressed at every opportunity" (17). Homer’s epics were written for an upper-class audience while Hesiod’s works were more pedestrian. In addition, "… Hesiod has allowed his world of primitive gods and chaotic forces to remain primitive and chaotic" (17).HYMN TO THE MUSES

In the opening lines of the poem, Hesiod gives credit to the nine Muses, who came to him while he was tending his sheep, for having taught him to sing. Speaking of himself in the third person, Hesiod wrote:The Muses once taught Hesiod to sing

Sweet songs, while he was shepherding his lambs

On holy Helicon; the goddesses

Olympian, daughters of Zeus who holds

The aegis, first addressed these words to me:

'You rustic shepherds, shame: belies you are

Not men!' (23-24)

Clio

However, Hesiod adds that while man knows enough to make up convincing lies, he still has the skill to speak the truth when needed. The Muses gave him a staff from a blooming laurel andbreathed a sacred voice into my mouthHe was instructed by the Muses to speak of those who will "live forever." Hesiod, thus, paid homage to the gods with a hymn to the nine Muses who had told the poet of times past. It was a time before the days of Zeus when the earth was born out of Chaos. They spoke of the rise of their father Zeus to the throne on Mount Olympus after his defeat of his own father, Kronos (Cronus):

With which to celebrate the things to come

And things which were before. (24)

We start then, with the Muses, who delightHesiod continues by hearing how the Muses celebrated both the "august race of the first-born gods" and Zeus, the father of both the gods and men. They tell him how Zeus eventually defeated Kronos and divided power among the other gods, most significantly with his brothers Poseidon and Hades. Hesiod tells of how Zeus became supreme,

With song the mighty mind of father Zeus

Within Olympus, telling of things that are

That will be, and that were, with voices joined

In harmony. The sweet sound flows from mouths

That never tire; the halls of father Zeus

The Thunderer, shine gladly when the pure

Voice of the goddesses is scattered forth. (24)

for he had beaten his father, Kronos, by force

And now divided power among the gods

Fairly, and gave appropriate rank to each. (25)

KRONOS/SATURN

BIRTH OF THE GODS

After the hymn to the Muses, Hesiod describes the birth of the gods. He asks the Muses to "give me sweet song" to tellhow the gods and earth arose at firstThey spoke of Chaos and how from Chaos came night and day. From Chaos came Earth (Gaia) who bore Heaven or Sky (Ouranos) as well as other children including Eros (Desire), Tartarus (Underworld), Erebus (Darkness), and Nyx (Night). From Nyx would come Doom, Dreams, Discord, Blame, and Sleep.

And rivers and the boundless swollen sea

And shining stars, and the broad heaven above

And how the gods divided up their wealth

and how they shared their honours, how they first

Captured Olympus with its many folds. (26)

Hesiod speaks of how Nyx also gave birth to the Destines and the merciless Fates,

who track down the sins of menHowever, from the "marriage" of Earth and Sky came the "crooked-scheming Kronos," the enemy of his father. All of the sons of Earth and Heaven - who would become known as the Titans - were hated by their jealous father from the moment of their birth. After each child was born, Ouranos would hide the babe deep in the Earth away from the light. However, their grief-stricken mother had a plan to repay his wicked crime. One evening, when Ouranos approached his wife, a hiding Kronos emerged and took a long-bladed sickle (given to him by his mother) and castrated his father. The dripping blood gave birth to both the Furies and the Giants. The severed genitals were thrown into the sea from which Aphrodite, the goddess of love, was born.

And gods, and ever cease from awful rage

Until they give the sinner punishment. (30)

The Birth of Aphrodite

Aside from the rise of Zeus and the battle with the Titans, much of the poem is spent on the birth of a variety of minor deities, among them Protho, Eukrante, Thetis, Hippothoe, and Cymtolge. Hesiod also tells of the marriage of Thaumas and Electra, who gave birth to the Harpies. Hesiod then speaks of the Gorgons and Medusa,…she who suffered painfullyAccording to legend, Medusa would die at the hands of Perseus (another son of Zeus), and when he severed her head,

Her sisters were immortal, always young

But she was mortal, and the Dark-haired one. (32)

… great Chrysaor sprang outThe poet speaks of the "unspeakable Cerberus,"

And Pegasus the horse, who is so called

Because his birth near to Ocean’s springs. (32)

who eats raw fleshHe wrote of the Hydra, Chimera, and the Nemean lion that would be defeated by the hero Hercules, the son of Zeus. Then there was the birth of Hekate (Hecate) daughter of Phoebe and granddaughter of the Titans,

The bronze-voiced hound of Hades, shameless, strong

With fifty heads. (33)

who, above all

Is honoured by the son of Kronos, Zeus

He gave her glorious gifts: a share of earth

And of the barren sea. In starry heaven

She has her place, and the immortal gods

Respect her greatly. (36)

ZEUS

ZEUS & KRONOS

Finally, Hesiod comes to the birth of Zeus:...father of gods and menRhea next gave birth to Hestia, Demeter, Hera, and Hades,

Whose thunder makes the wide earth tremble. (38)

who has his home beneath the earthHowever, Kronos seized each child and swallowed them, except, of course, Zeus who was stolen away by his mother to be reared in secret on the island of Crete. Kronos had learned from Earth and Heaven that his destiny was to be overthrown by one of his own. He believed that no one should be superior to the gods except himself. After the future king of the gods returned from his hiding place, he would rise up against his father and castrate him. Wender wrote that Hesiod did not dwell on Zeus’s attack of his father - not mentioning the castration - for he did not want the hero of the poem to demonstrate disrespect of a parent.

The god whose heart is pitiless, and him

Who crashes loudly and who shakes the earth. (38)

ATLAS & PROMETHEUS

Later, the poet introduces other notable figures of Greek mythology such as the offspring of the Titans. One of these, Atlas,forced by hard necessity

Holds the broad heaven up, propped on his head

And tireless hands, at the ends of Earth. (39)

Hercules and Atlas

Next, there was the birth of the "brilliant" Prometheus. However, Prometheus had angered the mighty father of the gods. He had tried to deceive Zeus and had stolen a ray of fire and given it to humanity, but Zeus did not want them to have fire. For this deception, the great god would have his revenge, and Prometheuswas bound by ZeusHercules, son of Alcmene and Zeus, would later free Prometheus from his chains.

In cruel chains, unbreakable, chained round

A pillar, and Zeus roused and set on him

An eagle with long wings, which came and ate

His deathless liver. But the liver grew

Each night, until it made up the amount

The long-winged bird had eaten in the day. (40)

THE FIRST WOMAN

In another important, if blatantly misogynistic episode, a young woman is created. Although not named, she was dressed by Athena in silver robes and from hercomes all the race of womankindLater Greek mythology speaks of Pandora, the wife of Epimetheus, who opens Pandora’s Box, an act that brought evil to the world. However, Pandora, by name, is not mentioned until Hesiod’s later work, the Works and Days. Hesiod wrote that a woman was bad for a man because she conspires. If a man avoids marriage and the difficulties it brings, he will be miserable in his old age because there will not be anyone to care for him; his relatives will divide his property upon his death. However, a married man with a good wife gets both good and bad but lives his entire life in everlasting pain.

The deadly female race and tribe of wives

Who live with mortal men and bring them harm

No help to them in dreadful poverty

But ready enough to share with them in wealth. (42)

The Titan Oceanus

THE BATTLE WITH THE TITANS

Long ago, a jealous and envious Ouranos had bound three of his sons - the Giants Kottos, Gyes, and Briateus - andmade them live beneath the broad-pathed earthHowever, Zeus was able to free them and a battle ensued between the Olympian gods, helped by the Giants, and the Titans. The war between the gods of Olympus and the Titans would last for ten years.

And there they suffered, living underground

Farthest away, at great earth’s edge; they grieved

For many years, with great pain in their hearts. (43)

They joined in hateful battle, all of themThe battle continued until

Both male and female. Titan gods and those

Whom Kronos sired and those whom Zeus had brought

To light from Erebos. Beneath the Earth

Strange, mighty ones, whose power was immense. (45)

Zeus no longer checked his rage, for nowThe Titans were defeated and sent to Tartarus deep beneath the earth. Those Giants Zeus had freed and fought alongside the Olympians were rewarded for their loyalty.

His heart was filled with fury, and he showed

The full range of his strength. (45)

THE CHILDREN OF ZEUS

The remainder of the poem is concerned with Zeus and the birth of his many children. His first wife was Metis, who bore him Athena. With Leto, he sired the twins Apollo and Artemis, the huntress. With Hera, his sister, Hebe, Ares, and Eileithuia were born. To Hera, "without the act of love" the limping god Hephaistos was born. From Mnemosyne came the nine Muses: Clio, Euterpe, Thalia, Melpomene, Terpsichore, Erato, Polyhymnia, Urania, and Calliope. After mentioning the many sons and daughters of Zeus’s offspring Hesiod ends his poem by saying,These are the goddesses who lay with men

And bore them children who were like the gods

Now sing of women, Muses

You sweet-voiced

Olympian daughters of aegis-bearing Zeus. (57)

Pilgrimage in the Byzantine Empire » Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

Pilgrimage in the Byzantine Empire involved the Christian faithful travelling often huge distances to visit such holy sites as Jerusalem or to see in person relics of holy figures and miraculous icons on show from Thessaloniki to Antioch. Well-worn routes resulted along which regular stopping points allowed pilgrims to sleep, eat, and be cared for in a network of monasteries and churches. For many pilgrims, their journey was the last they would ever make, and Jerusalem, especially, became a place where hospitals and hospices catered for the faithful until they were interred in the tombs they had pre-booked so as to rest in peace at the very centre of the Christian world.Golgotha Crucifix, Jerusalem

ORIGINS & PURPOSE OF PILGRIMAGE

Saint Helena, the mother of Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE), was one of the great founders of churches, notably in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, and it was during her visit to the Holy Land in 326 CE that she claimed to have discovered the True Cross, that is the actual wooden cross on which Jesus Christ was crucified. Helena is widely credited with being one of the most important figures in making pilgrimage fashionable amongst devout Christians. The practice got another boost when Constantine himself made a visit to Jerusalem in 335 CE.Pilgrimage really took off in the 5th and 6th centuries CE as other sacred sites sprang up across the empire. The skeletal remains, items of clothing, and tombs associated with holy figures, famous holy artworks and their potential for working miracles, the healing waters of sacred shrines, and even famous living holy men and women were all reasons for Christians to leave their homes and travel great distances. Pilgrimage in the Byzantine period was, though, less about making an arduous journey which had value in itself and more about getting to a final destination and being able to see and venerate Christianity’s treasures in person, to actually be for a time in the places where wondrous things had occurred in the distant past, and by so doing reaffirm one’s faith.BYZANTINE PILGRIMAGE WAS LESS ABOUT MAKING AN ARDUOUS JOURNEY & MORE ABOUT GETTING TO A FINAL DESTINATION TO SEE CHRISTIANITY’S TREASURES IN PERSON.

The travel plans of pilgrims were disrupted, if not actually ended, by the Arab conquest of the Levant by the mid-7th century CE. Byzantine armies reconquered parts of the Middle East in the 10th century CE, and the Crusaders, too, ensured a steady stream of pilgrims could still make the arduous journey to the Holy Land. Constantinople, too, was a major attraction to pilgrims from within and outside the empire’s territories and remained so until the 15th century CE.

THE HOLY LAND

Pilgrimage developed in the Byzantine period to such an extent that whole itineraries were made which spanned across the eastern part of the empire. The Holy Land was, of course, the most important and popular destination for pilgrims. Jerusalem was considered by Christians to be the centre of the world. The earliest surviving account of a Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem is by a pilgrim from Bordeaux who recorded his travels in 333 CE. The city really took off as a destination for pilgrims following Constantine I’s 4th-century CE sacred building programme there. The emperor set up lavish shrines at the Holy Sepulchre on Golgotha, where Christ was crucified and then entombed, the Mount of Olives, where the Ascension took place, and the nativity cave in Bethlehem.Reproduction of Madaba Mosaic

Other sites of interest in Jerusalem included the site of the Resurrection, Gethsemane, where Christ prayed on the eve of his death, the church of Holy Wisdom, where Christ was condemned, the birthplace of Saint Mary and her tomb, the cave of the Last Supper, and the tombs of Simeon and James. By the 4th century CE alone there were some 34 sites to be visited in the city and its environs, and these only grew over the centuries with more and more churches, especially, being built. Besides Bethlehem, other sites outside the city included the tomb of Lazarus in Bethany. There were also relics to be seen such as the very jugs which Jesus had used to turn water into wine at Cana and the notebook he had used as a child in Nazareth.

For many pilgrims, it was enough to visit the Holy Land and they had no thought of returning home. Many of the faithful wished to spend their dying days there, and hospices and monasteries sprang up to cater for them. Houses were rented out and tombs were built, all of which helped the Church fulfil its charity work for those pilgrims who could not pay their way.

A NETWORK OF SITES

Although the final destination of many pilgrims might have been Jerusalem, there were, along the way, many other stops of interest such as shrines set up in honour of important Christian figures. These shrines, dedicated to saints, martyrs and men and women who had witnessed Christ’s ministry, were usually furnished with impressive buildings or were part of monasteries that tended the shrines and offered accommodation to weary pilgrims. Travellers needed plenty of stops because their progress was slow, limited as they were to walking or riding a donkey. Ships made the voyage in quicker time, but even when they arrived at the Holy Land, there were still large distances to be covered. For example, a trip from Jerusalem to Mount Sinai, where Moses saw the burning bush and received the Ten Commandments, could take two weeks.Empire of Justinian I

The pilgrimage sites raised funds by charging pilgrims for their food and accommodation, renting out land they owned, and by receiving donations. Exemption from taxes helped too, as did the sales of the pilgrim souvenirs mentioned below.OTHER IMPORTANT SITES

The skeletal remains of Thomas the Apostle made Edessa in Syria a popular pilgrimage site which also had the prized mandylion, a holy cloth which had the impression of Christ on it. The image was copied in many wall-paintings and domes in churches around Christendom as it became the standard representation known as the Pantokrator (All-Ruler) with Christ full frontal holding a Gospel book in his left hand and performing a blessing with his right. Following the city’s siege in 944 CE the mandylion was taken to the royal palace in Constantinople.Ivory Pyxis Depicting Saint Menas

From the late 4th century CE Abu Mina near Alexandria was a major pilgrimage site as it boasted the tomb of Saint Menas, a martyr who died during the reign of Diocletian (284-305 CE). The site was a typical martyrion or martyr’s tomb with several splendid basilicas built around it. Especially popular in the 5th and 6th century CE, Abu Mina, like many other such sites, demonstrates that Christian shrines were often supported by imperial patronage.Qal’at Seman, just north of Antioch was another popular attraction as that was where the famous ascetic Symeon the Stylite the Elder (c. 389-459 CE) had stood on his column for 30 years in order to better contemplate God. When Symeon died, the site became one of pilgrimage with an octagonal church, two monasteries, several inns, and four basilicas built around the original column.

Ephesus was traditionally considered the home of several important holy Christian figures: Saint John the Evangelist, Saint Timothy, and Mary Magdalene. All had major shrines just outside the city, and John’s tomb was especially popular as the dust that was thought to regularly emit from its cracks was considered a cure-all. There was also the red stone said to have been used by Joseph of Arimathea when he washed the body of Christ prior to burial, a piece of the True Cross that John the Evangelist had worn around his neck, and the bonus attraction of the cave of the Seven Sleepers: seven young Christians who, under persecution in the mid-3rd century CE, had hidden in a cave and miraculously slept there for two centuries before emerging back into the world again.

Celsus Library, Ephesos

Other major pilgrimage sites on every dedicated pilgrim’s bucket list (and their associated holy figures,) included Seleucia in southern Asia Minor (Saint Thekla) with its impressive fortified monasteries, Hierapolis in Syria (Philip the Apostle), Euchaita in central Asia Minor (Saint Theodore), Myra in south-east Asia Minor (Saint Nicholas), Rome (Saint Paul and Peter), and Thessaloniki, where Saint Demetrius had a massive basilica dedicated to him.Finally, Constantinople, was itself, of course, an important point of pilgrimage, especially as emperors steadily removed relics from other cities. Jerusalem, for example, was plundered when it became increasingly threatened by the Arab caliphates. The mandylion and True Cross, as already noted, ended up in the Byzantine capital, as did the Crown of Thorns, the shroud, girdle and veil of the Virgin Mary, and the relics of the Apostles Luke, Timothy, and Andrew. There were many icons to be seen too, notably, the very first one said to have been painted by Saint Luke. Indeed, the city acquired such ecclesiastical riches that it became known as the New Jerusalem. Constantinople might have lost many of its treasures in 1204 CE during the Fourth Crusade but it acquired other relics over time and remained an attraction for pilgrims, especially from Russia, up to the 15th century CE.CONSTANTINOPLE WAS ITSELF AN IMPORTANT POINT OF PILGRIMAGE, ESPECIALLY AS EMPERORS STEADILY REMOVED RELICS FROM OTHER CITIES.

HOLY RELICS

For those who could not make it all the way to the Middle East or one of the other major sites, there was at least the chance to see relics and souvenirs in shrines elsewhere. Ornate receptacles were made (reliquaries) and put on display in shrines and churches across the empire which contained a portion of earth from the Mount of Olives, for example. Even holier relics included fragments of the bones or clothing of martyrs or pieces of wood and nails from the True Cross that Saint Helena had brought back to Constantinople and which subsequently spread across Christendom. These very holy items were often not on public display, or at least not permanently so that when they were put before the public gaze in their gem-studded boxes and ornate silver ampules, the effect was all the more mesmerising. Such rare public processions of relics and icons, perhaps only occurring once each year, were themselves a magnet for pilgrims.Icon of Christ Pantokrator

As the super-special first-hand holy relics were obviously in short supply, a whole secondary range of semi-relics (brandea) sprang up consisting of items which had been in contact with the original holy relics, oil being a prime example. Even representations of holy figures could take on a spiritual significance of their own. Icons are frequently recorded as having miraculously bled or wept, the figure's eyes may have moved or their halo glowed, all in response to a believer’s prayers. Whatever the form, access to relics and their spin-offs allowed pilgrims and believers to feel a little closer to the holy individuals they revered.PILGRIM SOUVENIRS

Pilgrims could purchase take-home souvenirs at many sacred sites, the most popular being blessed oil, water or earth from the holy location itself or which had been in contact with a holy relic. These liquids were kept in distinctive flat circular bottles, known as a pilgrim flasks (ampullae). Often highly decorated, they were usually made of terracotta but finer ones were made using tin and lead. The substance within the flasks was believed by many to function as an amulet, as a medicine or even as a miracle cure.Christian Pilgrim Bottle

Another souvenir, used for much the same purposes as the bottles, was the small disks made from pressed earth which had previously been sanctified. These medallions were decorated with a stamped blessing or image of a saint. In the case of Symeon the Stylite’s pilgrims, they got small tablets stamped with the ascetic’s image. Painted panels, ivory panels, and engraved prints were similarly bought as it was believed that, like the medallions, they had all somehow been in touch with a holy person - either directly having had contact with the person’s tomb or relics or simply because they represented that figure and had come from the holy site itself. Finally, for the big spender, there was the enkolpionwhich was an ornate necklace containing an icon or even an actual fragment of a holy relic. For pilgrims, all of these items acted as a tangible link to the divine, and they were frequently thought to protect the holder and ensure they overcame the dangers of ancient travel and finally got home safely.LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License