Asclepius › Ashoka › Death in Ancient Egypt » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Asclepius › Origins

- Ashoka › Origins

- Death in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Asclepius › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

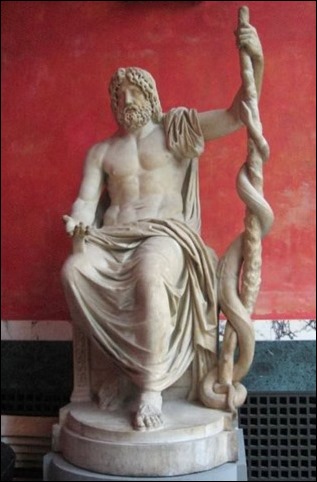

Asclepius was the ancient Greek god of medicine and he was also credited with powers of prophecy. The god had several sanctuaries across Greece ; the most famous was at Epidaurus which became an important centre of healing in both ancient Greek and Roman times and was the site of athletic, dramatic, and musical Games held in Asclepius' honour every four years.

ASCLEPIUS IN MYTHOLOGY

In Greek mythology Asclepius (or Asklepios ) was a demi-god hero as he was the son of divine Apollo , and his mother was the mortal Koronis from Thessaly. In some accounts Koronis abandoned her child near Epidaurus in shame for his illegitimacy and left the baby to be looked after by a goat and a dog. However, in a different version of the story Koronis was killed by Apollo for being unfaithful, whilst, in yet another version, the Messenian Arsinoe was the unfortunate mother of Asclepius.

The motherless Asclepius was then brought up by his father who gave him the gift of healing and the secrets of medicine using plants and herbs. Asclepius was also tutored by Cheiron, the wise centaur who lived on Mt. Pelion. Asclepius had many children - two sons: Machaon and Podaleirios, and four daughters: Iaso, Panacea, Aceso, and Aglaia. In some traditions he was married to Hygeia, also a goddess of health; in another version she was his daughter and Asclepius married Epione. The descendants of Asclepius, who continued in the art of medicine and healing, were known as the Asclepiads. Machaon, for example, helped Menelaos when he was wounded in the Trojan War , but the most famous doctor of the family was undoubtedly Hippocrates .

ZEUS SAW ASCLEPIUS AND HIS MEDICAL SKILLS AS A THREAT TO THE ETERNAL DIVISION BETWEEN HUMANITY AND THE GODS.

Asclepius met a tragic end when he was killed by a thunderbolt thrown by Zeus. This was because the father of the gods saw Asclepius and his medical skills as a threat to the eternal division between humanity and the gods, especially following rumours that Asclepius' healing powers were so formidable that he could even raise the dead (for which he used the blood of Medusa given to him by Athena ). Apollo protested against his son's treatment but was himself punished by Zeus for impiety and made to serve Admetos, the king of Thessaly, for one year. Asclepius himself was deified following his death, and in some local myths he also became the constellation Ophiuchus.

EPIDAURUS

The god was particularly worshipped at the sanctuary of Epidaurus (founded in the 6th century BCE), known as the Asklepieion, because he was believed to have been born on the nearby Mt. Titthion. The site, the most important healing centre in the ancient world, was visited from all over Greece by those seeking alleviation of their ailments by either divine intervention or medicines administered by the resident priests and it had many important buildings. These included a large temple (380-375 BCE) which contained a larger than life-size statue of Asclepius by Thrasymedes and the Thymele (360-330 BCE) - a round marble building which had a mysterious underground labyrinth , perhaps containing snakes. These were associated with Asklepius and symbolised regeneration, as snakes were thought to live both below and above ground and were also connected to prophecy as they knew the hidden secrets below ground.

At Epidaurus there was also the columned Abato or Enkoimeterion in which patients, after having gone through several purification rituals, slept overnight and awaited dreams where the god would appear and offer cures and remedies. The cures would then later be self-administered or carried out by resident priests in the more complex cases. Thankful patients often left votive offerings at the site, sometimes depicting the body part which had been cured. The site also had a 6000 seat theatre (340-330 BCE) which is the best preserved theatre in Greece and still in use today.

Theatre of Epidaurus

Epiduarus was also the site of the pan - Hellenic Asklepieia festival, founded in the 5th century BCE and held every four years to celebrate theatre, sport, and music in honour of Asclepius. The site continued to be important in Roman times, and several buildings were added in the 2nd century CE under the auspices of the Roman senator Antonius. The sanctuary finally closed in 426 CE when emperor Theodosius II decreed the closure of all pagan sites in Greece.

OTHER SANCTUARIES

Another important sanctuary in Asclepius' name was in Athens , situated just below the acropolis on the western slope.Tradition said that a priest named Telemachos brought the god to the site in the form of a sacred snake in 419 BCE. Strabo also mentions that the oldest sanctuary to Asclepius was at Tricca, where in some accounts the god was born, but the site has never been discovered. Messene does, however, have important archaeological remains attesting to the popularity of its Asclepian sanctuary in Hellenistic times. Other sacred sites were located on the island of Kos which also had an important school of physicians from the 5th century BCE, on, and at Tegea . The cult of Asclepius was also transferred to Pergamonsometime in the 4th century BCE, possibly by a healed patient at Epidaurus named Archias. Finally, in 293 BCE the Romans were said to have taken the sacred snake from Epidaurus to the Tiber Island in order to cure a plague, although there is evidence of the cult of Asclepius on the Italian mainland from as early as the 5th century BCE.

ASCLEPIUS IN ART

In ancient Greek art, Asclepius was portrayed in sculpture, on pottery , in mosaics, and on coins. Almost always, the god has a full beard, wears a simple himation robe, and holds a staff (the bakteria ) with a sacred snake coiled around it. He is sometimes accompanied by Hygeia and occasionally has a dog at his feet, as these animals were sacred at some of the god's sanctuaries. The god was also associated with three types of tree: the cypress, pine, and olive. Art works from as far afield as Dion, Kos, Athens, and Rhodes dating from the 4th century BCE to the 3rd century CE attest to the god's widespread and long-lived popularity.

Ashoka › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Cristian Violatti

Emperor Ashoka the Great (sometimes spelt Aśoka) lived from 304 to 232 BCE and was the third ruler of the Indian Mauryan Empire , the largest ever in the Indian subcontinent and one of the world's largest empires at its time. He ruled form 268 BCE to 232 BCE and became a model of kingship in the Buddhist tradition. Under Ashoka India had an estimated population of 30 million, much higher than any of the contemporary Hellenistic kingdoms. After Ashoka's death, however, the Mauryan dynasty came to an end and its empire dissolved.

THE GOVERNMENT OF ASHOKA

In the beginning, Ashoka ruled the empire like his grandfather did, in an efficient but cruel way. He used military strength in order to expand the empire and created sadistic rules against criminals. A Chinese traveller named Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang) who visited India for several years during the 7th century CE, reports that even during his time, about 900 years after the time of Ashoka, Hindu tradition still remembered the prison Ashoka had established in the north of the capital as “Ashoka's hell”.Ashoka ordered that prisoners should be subject to all imagined and unimagined tortures and nobody should ever leave the prision alive.

During the expansion of the Mauryan Empire, Ashoka led a war against a feudal state named Kalinga (present day Orissa) with the goal of annexing its territory, something that his grandfather had already attempted to do. The conflict took place around 261 BCE and it is considered one of the most brutal and bloodiest wars in world history. The people from Kalinga defended themselves stubbornly, keeping their honour but losing the war: Ashoka's military strength was far beyond Kalinga's.The disaster in Kalinga was supreme: with around 300,000 casualties, the city devastated and thousands of surviving men, women and children deported.

INDIA WAS TURNED INTO A PROSPEROUS AND PEACEFUL PLACE FOR YEARS TO COME.

What happened after this war has been subject to numerous stories and it is not easy to make a sharp distinction between facts and fiction. What is actually supported by historical evidence is that Ashoka issued an edict expressing his regret for the suffering inflicted in Kalinga and assuring that he would renounce war and embrace the propagation of dharma . What Ashoka meant by dharma is not entirely clear: some believe that he was referring to the teachings of the Buddha and, therefore, he was expressing his conversion to Buddhism . But the word dharma , in the context of Ashoka, had also other meanings not necessarily linked to Buddhism. It is true, however, that in subsequent inscriptions Ashoka specifically mentions Buddhist sites and Buddhist texts, but what he meant by the word dharma seems to be more related to morals, social concerns and religious tolerance rather than Buddhism.

THE EDICTS OF ASHOKA

After the war of Kalinga, Ashoka controlled all the Indian subcontinent except for the extreme southern part and he could have easily controlled that remaining part as well, but he decided not to. Some versions say that Ashoka was sickened by the slaughter of the war and refused to keep on fighting. Whatever his reasons were, Ashoka stopped his expansion policy and India turned into a prosperous and peaceful place for the years to come.

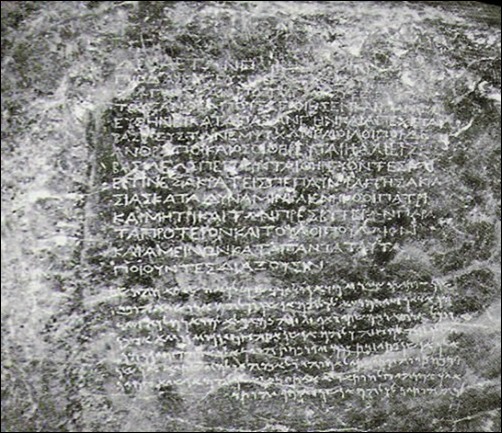

Ashoka began to issue one of the most famous edicts in the history of government and instructed his officials to carve them on rocks and pillars, in line with the local dialects and in a very simple fashion. In the rock edicts, Ashoka talks about religious freedom and religious tolerance, he instructs his officials to help the poor and the elderly, establishes medical facilities for humans and animals, commands obedience to parents, respect for elders, generosity for all priests and ascetic orders no matter their creed, orders fruit and shade trees to be planted and also wells to be dug along the roads so travellers can benefit from them.

However attractive all this edicts might seem, the reality is that some sectors of Indian society were truly upset about them.Brahman priests saw in them a serious limitation to their ancient ceremonies involving animal sacrifices, since the taking of animal life was no longer an easy business and hunters along with fishermen were equally angry about this. Peasants were also affected by this and were upset when officials told them that “chaff must not be set on fire along with the living things in it”.Brutal or peaceful, it seems that no ruler can fully satisfy the people.

Greek and Aramaic inscriptions by king Ashoka

THE PATRONAGE OF BUDDHISM

The Buddhist tradition holds many legends about Ashoka. Some of these include stories about his conversion to Buddhism, his support of the monastic Buddhist communities, his decision to establish many Buddhist pilgrimage sites, his worship of the bodhi tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment, his central role organizing the Third Buddhist Council, followed by the support of Buddhist missions all over the empire and even beyond as far as Greece , Egypt and Syria . The Buddhist Theravada tradition claims that a group of Buddhist missionaries sent by Emperor Ashoka introduced the Sthaviravada school (a Buddhist school no longer existent) in Sri Lanka, about 240 BCE.

It is not possible to know which of these claims are actual historical facts. What we do know is that Ashoka turned Buddhism into a state religion and encouraged Buddhist missionary activity. He also provided a favourable climate for the acceptance of Buddhist ideas, and generated among Buddhist monks certain expectations of support and influence on the machinery of political decision making. Prior to Ashoka Buddhism was a relatively minor tradition in India and some scholars have proposed that the impact of the Buddha in his own day was relatively limited. Archaeological evidence for Buddhism between the death of the Buddha and the time of Ashoka is scarce; after the time of Ashoka it is abundant.

Was Ashoka a true follower of the Buddhist doctrine or was he simply using Buddhism as a way of reducing social conflict by favouring a tolerant system of thought and thus make it easier to rule over a nation composed of several states that were annexed through war? Was his conversion to Buddhism truly honest or did he see Buddhism as a useful psychological tool for social cohesion? The intentions of Ashoka remain unknown and there are all types of arguments supporting both views.

ASHOKA'S LEGACY

The myths and stories about Ashoka propagating Buddhism, distributing wealth, building monasteries, sponsoring festivals, and looking after peace and prosperity served as an inspiring model of a righteous and tolerant ruler that influenced monarchs from Sri Lanka to Japan . A particular story telling that Ashoka built 84,000 stupas (commemorative Buddhists buildings used as a place of meditation), served as an example to many Chinese and Japanese rulers who imitated Ashoka's initiative.

He did with Buddhism in India what Emperor Constantine did with Christianity in Europe and what the Han dynasty did with Confucianism in China : he turned a tradition into an official state ideology and thanks to his support Buddhism ceased to be a local Indian cult and began its long transformation into a world religion. Eventually Buddhism died out in India sometime after Ashoka's death, but it remained popular outside its native land, especially in eastern and south-eastern Asia. The world owes to Ashoka the growth of one of the world's largest spiritual traditions.

Death in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

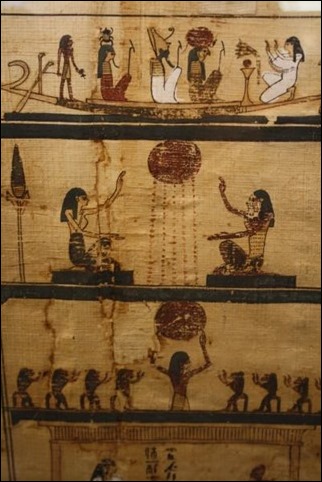

To the ancient Egyptians, death was not the end of life but only a transition to another plane of reality. Once the soul had successfully passed through judgment by the god Osiris , it went on to an eternal paradise, The Field of Reeds, where everything which had been lost at death was returned and one would truly live happily ever after. Even though the Egyptian view of the afterlife was the most comforting of any ancient civilization , people still feared death. Even in the periods of strong central government when the king and the priests held absolute power and their view of the paradise-after-death was widely accepted, people were still afraid to die.

The rituals concerning mourning the dead never dramatically changed in all of Egypt 's history and are very similar to how people react to death today. One might think that knowing their loved one was on a journey to eternal happiness, or living in paradise, would have made the ancient Egyptians feel more at peace with death, but this is clearly not so. Inscriptions mourning the death of a beloved wife or husband or child - or pet - all express the grief of loss, how they miss the one who has died, how they hope to see them again someday in paradise - but not expressing the wish to die and join them anytime soon.There are texts which express a wish to die, but this is to end the sufferings of one's present life, not to exchange one's mortal existence for the hope of eternal paradise.

Book of the Dead of Aaneru

The prevailing sentiment among the ancient Egyptians, in fact, is perfectly summed up by Hamlet in Shakespeare's famous play: "The undiscovered country, from whose bourn/No traveler returns, puzzles the will/And makes us rather bear those ills we have/Than fly to others that we know not of" (III.i.79-82). The Egyptians loved life, celebrated it throughout the year, and were in no hurry to leave it even for the kind of paradise their religion promised.

THE DISCOURSE BETWEEN A MAN AND HIS SOUL

A famous literary piece on this subject is known as Discourse Between a Man and his Ba (also translated as Discourse Between a Man and His Soul and The Man Who Was Weary of Life ). This work, dated to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt(2040-1782 BCE), is a dialogue between a depressed man who can find no joy in life and his soul which encourages him to try to enjoy himself and take things easier. The man, at a number of points, complains how he should just give up and die - but at no point does he seem to think he will find a better existence on the 'other side' - he simply wants to end the misery he is feeling at the moment. The dialogue is often characterized as the first written work debating the benefits of suicide, but scholar William Kelly Simpson disagrees, writing :

What is presented in this text is not a debate but a psychological picture of a man depressed by the evil of life to the point of feeling unable to arrive at any acceptance of the innate goodness of existence. His inner self is, as it were, unable to be integrated and at peace. His dilemma is presented in what appears to be a dramatic monologue which illustrates his sudden changes of mood, his wavering between hope and despair, and an almost heroic effort to find strength to cope with life. It is not so much life itself which wearies the speaker as it is his own efforts to arrive at a means of coping with life's difficulties. (178)

As the speaker struggles to come to some kind of satisfactory conclusion, his soul attempts to guide him in the right direction of giving thanks for his life and embracing the good things the world has to offer. His soul encourages him to express gratitude for the good things he has in this life and to stop thinking about death because no good can come of it. To the ancient Egyptians, ingratitude was the 'gateway sin' which let all other sins into one's life.

TO THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS, INGRATITUDE WAS THE 'GATEWAY SIN' WHICH LET ALL OTHER SINS INTO ONE'S LIFE.

If one were grateful, then one appreciated all that one had and gave thanks to the gods; if one allowed one's self to feel ungrateful, then this led one down a spiral into all the other sins of bitterness, depression, selfishness, pride, and negative thought. The message of the soul to the man is similar to that of the speaker in the biblical book of Ecclesiastes when he says, "God is in heaven and thou upon the earth; therefore let thy words be few" (5:2).

The man, after wishing that death would take him, seems to consider the words of the soul seriously. Toward the end of the piece, the man says, "Surely he who is yonder will be a living god/Having purged away the evil which had afflicted him...Surely he who is yonder will be one who knows all things" (142-146). The soul has the last word in the piece, assuring the man that death will come naturally in time and life should be embraced and loved in the present.

THE LAY OF THE HARPER

Another Middle Kingdom text, The Lay of the Harper , also resonates with the same theme. The Middle Kingdom is the period in Egyptian history when the vision of an eternal paradise after death was most seriously challenged in literary works. Although some have argued that this is due to a lingering cynicism following the chaos and cultural confusion of the First Intermediate Period , this claim is untenable. The First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 BCE) was simply an era lacking a strong central government, but this does not mean the civilization collapsed with the disintegration of the Old Kingdom , simply that the country experienced the natural changes in government and society which are a part of any living civilization.

The Lay of the Harper is even more closely comparable to Ecclesiastes in tone and expression as seen clearly in the refrain: "Enjoy pleasant times/And do not weary thereof/Behold, it is not given to any man to take his belongings with him/Behold, there is no one departed who will return again" (Simpson, 333). The claim that one cannot take one's possessions into death is a direct refutation of the tradition of burying the dead with grave goods: all those items one enjoyed and used in life which would be needed in the next world.

Book of the Dead of Tayesnakht

It is entirely possible, of course, that these views were simply literary devices to make a point that one should make the most of life instead of hoping for some eternal bliss beyond death. Still, the fact that these sentiments only find this kind of expression in the Middle Kingdom suggests a significant shift in cultural focus. The most likely cause of this is a more 'cosmopolitan' upper class during this period, which was made possible precisely by the First Intermediate Period, which 19th- and 20th-century CE scholarship has done so much to vilify. The collapse of the Old Kingdom of Egypt empowered regional governors and led to greater freedom of expression from different areas of the country instead of conformity to a single vision of the king.

The cynicism and world-weary view of religion and the afterlife disappear after this period and New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE) literature again focuses on an eternal paradise which waits beyond death. The popularity of The Book of Coming Forth by Day (better known as The Egyptian Book of the Dead ) during this period is amongst the best evidence for this belief. The Book of the Dead is an instructional manual for the soul after death, a guide to the afterlife, which a soul would need in order to reach the Field of Reeds.

ETERNAL LIFE

The reputation Ancient Egypt has acquired of being 'death-obsessed' is actually undeserved; the culture was obsessed with living life to its fullest. The mortuary rituals so carefully observed were intended not to glorify death but to celebrate life and ensure it continued. The dead were buried with their possessions in magnificent tombs and with elaborate rituals because the soul would live forever once it has passed through death's doors.

While one lived, one was expected to make the most of the time and enjoy one's self as much as one could. A love song from the New Kingdom of Egypt , one of the so-called Songs of the Orchard , expresses the Egyptian view of life perfectly. In the following lines, a sycamore tree in the orchard speaks to one of the young women who planted it when she was a little girl:

Give heed! Have them come bearing their equipment,

Bringing every kind of beer , all sorts of bread in abundance

Vegetables, strong drink of yesterday and today,

And all kinds of fruit for enjoyment.

Come and pass the day in happiness,

Tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow,

Even for three days, sitting beneath my shade.

(Simpson, 322)

Although one does find expressions of resentment and unhappiness in life - as in the Discourse Between a Man and his Soul - Egyptians, for the most part, loved life and embraced it fully. They did not look forward to death or dying - even though promised the most ideal afterlife - because they felt they were already living in the most perfect of worlds. An eternal life was only worth imagining because of the joy the people found in their earthly existence. The ancient Egyptians cultivated a civilization which elevated each day to an experience in gratitude and divine transcendence and a life into an eternal journey of which one's time in the body was only a brief interlude. Far from looking forward to or hoping for death, the Egyptians fully embraced the time they knew on earth and mourned the passing of those who were no longer participants in the great festival of life.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License