Argos › Aria › Early Human Migration » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Argos › Who was

- Aria › Origins

- Early Human Migration › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Argos › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Argos lies on the fertile Argolid plain in the eastern Peloponnese in Greece . The site has been inhabited from prehistoric times up to the present day. Ancient Argos was built on two hills: Aspis and Larissa, 80 m and 289 m in height respectively.Argos, along with Mycenae and Tiryns , was a significant Mycenaean centre, and the city remained important throughout the Greek , Hellenistic , and Roman periods until its destruction by the Visigoths in 395 CE.

In ancient Greek mythology , the city gained its name from Argos, son of Zeus and Niobe. Homer ’s Iliad tells of Argos sending men to fight in the Trojan War , as being ruled by Agamemnon , and as a place celebrated for its horse rearing. The city is also described by Homer as being especially dear to the goddess Hera .

THE CITY'S MYTHICAL HERITAGE MEANT ARGOS ENJOYED A CERTAIN PRESTIGE EVEN IN ROMAN TIMES.

The city perhaps reached its greatest dominance in the 7th century BCE under King Pheidon, who is credited with introducing to mainland Greece such military innovations as hoplite tactics and double grip shields. From the 7th to 5th century BCE, the city was a long-time rival to Sparta for dominance of the Argolid. The role of Argos during the Persian wars of the 5th century BCE is ambiguous, the city either remaining neutral or displaying pro-Persian sentiment. Nevertheless, it was during this century that Argos began to assimilate smaller surrounding states such as Tiryns, Mycenae, and Nemea . It was as part of this expansion that Argos also took over as host of the biennial Panhellenic games originally held at Nemea, firstly from c. 415 BCE to c. 330 BCE, and again definitively from 271 BCE. This fact and the city's mythical heritage meant Argos enjoyed a certain prestige even in Roman times. Hadrian , in particular, was generous to the city, building, amongst other things, an aqueduct and baths.

Theatre of Argos

Visible today are Mycenaean tombs (14th to 13th century BCE), a theatre (4th to 3rd century BCE, with 2nd and 4th century CE modifications), an odeum for dramatic and musical performances (5th century BCE), the sanctuary of Aphrodite (430-420 BCE), foundations and walls of the agora (5th century BCE), Roman baths or thermae (2nd century CE), and parts of the ancient, Cyclopean, citadel walls (incorporated into the medieval fortress fortifications on the Larissa hill). The theatre is particularly well preserved and includes 81 rows of seats which would have given it a capacity of 20,000 spectators - the largest of any Greek theatre .

Argos was excavated principally by the French School of Archaeology , and various artefacts have been found at the site including terracotta figurines (13th century BCE), pottery in the geometric style (8th century BCE), armour (7th century BCE), Roman sculpture , and two 4th-5th century CE mosaic floors depicting Dionysos and the months of the year. Most of these now reside in the Archaeological Museum of Argos.

Aria › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Antoine Simonin

Aria was always understood to be the area around the Areios River, today Hari Rud in Afghanistan (Arrian, 'Anabasis' IV.6.6).It was bounded to the north by Margiana and Baktria, where the area of the Margos River begins; to the west by the big Carmanian desert; to the south by Drangiana; and to the east by the mighty Paropamisadai mountains. The Areios was the backbone of the region, flowing across the land: Aria corresponds almost exactly to the modern province of Herat, which shows the importance of the river throughout history. The productive part of Areia was a rather narrow stretch of land that is some 150 km along both banks of the Areios. At no point along its route was the valley more than 25 km wide, even if some lakes can be found as mentioned in the Avesta (Vendidad, Fargard I.9). Nevertheless, strongly linked to its river, the area was known to be fertile and to produce some of the best wines in the world. Its capital was Alexandria of Aria (modern Herat), the ancient Artacoana. The land was divided, according to Ptolemy (VI.17) between the area near of the river, inhabited by settled Arians in towns and villages, and the nomadic tribes in the surrounding mountains and deserts. Ptolemy listed many towns, confirming the idea that the area was powerful at this time.

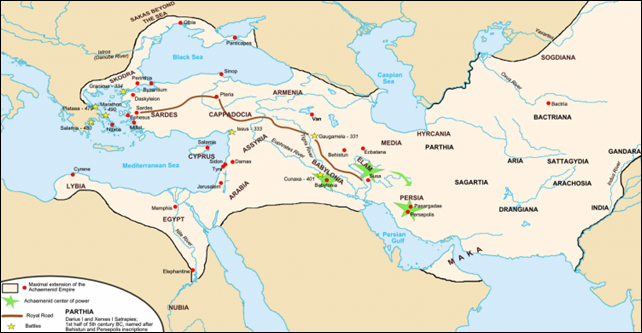

Its population was divided between settled people in the numerous towns of the plain and the nomads of the deserts and mountains. Its history reproduced the same outline between Persians, Greeks, Parthians and Sakas. Although little is known of early Aria, the area became a Persian satrapy when it was conquered by Cyrus . Artacoana (modern Herat) and became the capital of the region. Aria was, at this time, an important part of the Achaemenid Empire , and Strabo (XI.10.1) even relates that Drangiana was an administrative part of Aria. It seems that Arians were strongly influenced by northern Scythian peoples, as it is possible to see in Achaemenid representations of Arians at Susa and Persepolis .

WHEN ALEXANDERINVADED CENTRAL ASIA, HE ARRIVED IN ARIA IN 330 BCE AND WAS RECEIVED BY THE SATRAP SATIBARZANES.

When Alexander invaded Central Asia, he arrived in Aria in 330 BCE and was received by the satrap of the area, called Satibarzanes. Arrian ('Anabasis' III. 25) tells us that the satrap betrayed Alexander, so the Macedonian was forced to besiege Artacoana. Alexander used siege towers to take Artacoana and succeeded in doing so; the inhabitants were killed or sold as slaves. The empty town was rebuilt and called Alexandria. Aria was one of the easternmost parts of the Seleucid Empire but was, at least in part, conceded to Chandragupta Maurya after the war between this Indian king and Seleucos in 303 BC (Strabo XV.2-9).

When Diodotos made Baktria independent in 250 BCE, Aria became, nevertheless, quickly conquered and administered by the Greco-Bactrian kings. The only battle we know from Greco-Bactrian kings was fought in Aria, between Antiochos III and Euthydemos, during which Euthydemos' cataphracts were crushed by the Seuleucid's cavalry ( Polybius , "Histories", X.27-31). Sources are scarce, but the area seems to have remained under Greek control until the Parthian invasion of Greco-Bactrian lands in the 140s BCE during Mithridates' rule. In the following decades, groups of Sakas, that were pushed by the northern Yuezhei, began to settle in the area. To what extent those Sakas controlled Aria we do not know, but it seems that the area continued being less or more a dependancy of the Parthians through most of their history since Mithridates, and then under Kushan rule.

Early Human Migration › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Emma Groeneveld

Disregarding the extremely inhospitable spots even the most stubborn of us have enough common sense to avoid, humans have managed to cover an extraordinary amount of territory on this earth. Go back 200,000 years, however, and Homo sapiens was only a newly budding species developing in Africa, while perceived ancestors such as Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis had already travelled beyond Africa to explore parts of Eurasia, and sister species like the Neanderthal and Denisovan would traipse around there way before we did, too.

How, when, and why both fellow Homo species and our own Homo sapiens started moving all over the place is hotly debated.The story of early human migration covers such an immense time span and area that there cannot be but one explanation for all of these groups of adventurous hunter-gatherers going wandering around. Where for some groups a change in climate may have pushed them to seek more hospitable lands, others may have been looking for better food sources, avoiding hostile or competing neighbours, or may have simply been curious risk-takers wanting a change of scenery. This puzzle is further complicated by the fact that only a highly fragmentary fossil record exists (and we do not know exactly how fragmentary it is, or which bits are missing). Recently, the field of genetics has shot to the forefront by analysing ancient DNA, adding to the fossil, climatic, and geological data, so that hopefully we can attempt to piece together a story from all these titbits.

Map of Homo Sapiens Migration

This story will keep changing, however - at least in the details but perhaps even amounting to considerable overhauls - as new bones are dug up, tools are found, and more DNA is studied with increasing accuracy. Here, a basic overview will be provided based on what we think we know right now, alongside a discussion of the possible motivations these many different early humans may have had to migrate away from their homelands, across the far reaches of our globe.

EARLY TRANSCONTINENTAL ADVENTURERS

HOMO FLORESIENSIS, FOUND AT LIANG BUA IN INDONESIA, MAY BE DESCENDANT FROM A VERY EARLY & STILL UNKNOWN MIGRATION FROM AFRICA.

Already millions of years ago, middle and late Miocene hominoids - among which were the ancestors of our species of Homoas well as of the great apes - were present not just in Africa but also in parts of Eurasia. Our own branch developed in Africa, though; the Australopithecines , our supposed ancestors, lived in East and South Africa's grasslands. The earliest Homo to be securely found outside of Africa is Homo erectus , and when interpreted in the broad sense (there is some dispute over which fossils should be included within the species) it is seen to have set the bar high, spanning an impressive geographical range indeed. However, the very tricky to place species of Homo floresiensis (nicknamed 'hobbit'), found at Liang Bua in Indonesia, must be named, too; it may be descendant from a very early (before or not long after Erectus ) and still unknown migration from Africa. We do not know enough yet to truly verify this or to fill in the details, though, so the consensus favours Erectus as first globetrotting humans for now.

Popping up in East Africa at sites such as Olduvai Gorge in the Turkana Basin in Kenya, from roughly 1,9 million years ago onwards, Homo erectus is also seen in South and North Africa. They are generally thought to have gone wandering out of Africa by 1,9-1,8 million years ago, travelling through the Middle East and the Caucasus and onwards towards Indonesia and China , which they reached around 1,7-1,6 million years ago. Erectus may even have braved the normally cold north of China in a period with somewhat milder temperatures, as early as roughly 800,000 years ago.

THE FOLLOW-UP CREW

Erectus had set the trend for far-reaching early human migration, and their successors would push the boundaries further still.By around 700,000 years ago (and perhaps as early as 780,000 years ago), Homo heidelbergensis is thought to have developed from Homo erectus within Africa. There, different bands made territories within East, South, and North Africa their own. Of course, migration within Africa itself also occurred, in general.

From there on, a particularly energetic group of Homo heidelbergensis spread out all the way through western Eurasia, crossing the major mountain ranges of Europe and making it as far north as England and Germany. This is Ice Age Europe we are talking about, and these humans would have had to flow along with the often-changing climate; they were quite good at coping with the colder conditions of Europe and were able to survive on the southern edge of the subarctic zone, but naturally avoided the actual ice sheets. Evidence from Pakefield and Happisburgh in England, for instance, shows that early humans around 700,000 years ago were indeed able to make it this far north when the climate was more temperate, while they probably edged back into southern refuges during colder stages.

Homo Heidelbergensis & Early Neanderthal Fossil Sites

The same high mobility and adaptability were required by the species the Eurasian portion of Heidelbergensis gradually developed into – the Neanderthals, whose core homeland is thought to have been Europe. They moved out into new territories and new climatic zones until they could be found all the way from Spain and the Mediterranean, throughout Northern Europe and Russia, the Near East ( Israel , Syria , Turkey , Iraq), to as far east as Siberia and Uzbekistan. At this eastern edge, they may have overlapped slightly in territory with another species that may also have covered a fair bit of ground: the Denisovans.This sister species to the Neanderthals is so far only known from a finger bone and a tooth found in a cave in the Altai Mountains in Siberia, but genetic evidence suggests the Denisovans may have lived across a range spanning from Siberia all the way to Southeast Asia.

HOMO SAPIENS SPREADS OUT

Meanwhile, Homo sapiens gradually began to emerge, most likely from Heidelbergensis ancestors within the rich territories of Africa, in either Africa's southern or eastern reaches, around 200,000 years ago. Many sites have been found in both these regions that show that early bands of anatomically modern humans successfully lived there.

Pioneering bands of humans then managed to migrate away from these homelands and into the Near East, where Homo sapiens burials have been uncovered at the sites of Skhul and Qafzeh in Israel, dated to between 90,000 and a staggering 130,000 years old. Similarly, the site of Jebel Faya in the United Arab Emirates seems to show through the tools that were found there that Homo sapiens may have migrated here as early as 130,000 years ago, too. A recent study has shown that some of these early adventurers made it all the way to the island of Sumatra in western Indonesia between 73,000 and 63,000 years ago; this ties in well with other evidence that hints at humans reaching inner Southeast Asia some time before 60,000 years ago, and then following the retreating glaciers up towards the north. There is even new evidence that places humans in the north of Australia by 65,000 years ago, perhaps also stemming from an earlier migration.

Skhul Cave, Israel

These initial modern human forays into the lands beyond Africa are dwarfed by a later migration, however. Around 55,000 years ago, what is now seen as the main wave (or, perhaps, waves) of anatomically modern humans made an effort that proved very successful indeed; larger numbers than before spread out rapidly across Eurasia and the rest of the Old World, eventually ending up covering the globe. The people involved in this recent 'Out of Africa' event seem to be directly connected with all present-day non-Africans, and as such, they are thought to have replaced or absorbed most of the humans that were already in all sorts of corners of the world ahead of this time.

HOMO SAPIENS MET NEANDERTHALS & INTERBRED WITH THEM, AFTER WHICH AN OFFSHOOT BRANCHED OFF & EVENTUALLY MIGRATED INTO EUROPE AROUND 45,000 YEARS AGO.

But which route did they take on this huge trek? Regarding possible ways out of Africa, Egypt is an option, but so is a journey through 'wet' corridors in the Sahara, through East Africa and into the Levant . Once out, we know through genetic research that in this Near Eastern setting, humans met Neanderthals and interbred with them, after which an offshoot branched off and eventually migrated into Europe around 45,000 years ago. Homo sapiens also continued towards the east, though, probably all the way along the coastline, through India and into Southeast Asia, where they may have bumped into the possibly resident Denisovans and interbred with them (it is clear interbreeding happened somewhere, and the most likely location seems to be Southeast Asia).

All of this apparently happened at record speed; already by 53,000 years ago, descendants of that main wave out of Africa reached the north of Australia, the south taking until around 41,000 years ago. Reaching it was not straightforward, though.Although sea levels were about 100 meters lower than today, there was still a slightly inconvenient amount of water – a stretch of some 70 km - standing in between these early Homo sapiens in Asia and the landmass that included Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea. Rather than surviving such a swim, they probably built boats or rafts to help them on this gutsy crossing.

Meanwhile, within Asia, a migration towards the north of East Asia could have begun around 40,000 years ago, paving the way to the Bering Land Bridge – a happy grassland steppe-covered side effect of the Ice Age, connecting Asia to the Americas.Humans are usually thought to have reached the Americas through this route, by around 15,000 years ago, expanding downwards along the coast or through an ice-free corridor in the interior, but this is far from a closed case. After this, there were some last strongholds that remained human-free for a long time still, such as Hawaii – reached by boat around 100 CE – and New Zealand, which held out until around 1000 CE.

POSSIBLE DRIVING FORCES

The question of why these prehistoric people decided to leave and move somewhere else is a tough nut to crack, especially considering we are looking at a time that predates written sources. Migration is generally seen a result of push and pull factors, though, so that is a place to start. Push factors relate to the circumstances that can make someone's homeland an unpleasant enough place for them to ditch it entirely in favour of something new. With regard to these early human migrations, of course 'no jobs' or 'terrible political circumstances' do not apply; rather, think of stuff like the climate taking a turn for the worse and turning places into huge ovens or freezers where barely anything can live or grow, natural disasters, competition with hostile neighbouring groups, food and other resources running too low to support the amount of people within an area, or the more mobile type of food (herds of herbivores) migrating away.

Pull factors, on the other hand, involve the draw of new possibilities and rewards; basically, the more favourable side of the things mentioned in the 'push' section, such as greener lands with better climates and luscious amounts of food and resources.Of course, this is a bit of a simplification, and it will be hard to track down the exact combination of factors that led to each individual instance of early human migration.

There are some prerequisites for successfully handling migration. It is stressful and dangerous – Homo erectus , for instance, most likely had no idea what they would find when they left Africa – and it challenges a group's resourcefulness and ability to adapt. If you move into a new environment, it helps to have adequate technology to help you tackle it; in this case, tools to successfully hunt and gather the resident animals and plants, or to protect yourself against colder areas via clothing or fire (the latter has been known by humans since probably at least 1,8 million years ago, but was not habitually used until probably between 500,000-400,000 years ago). Inventiveness and cooperation in securing new resources also help.

Woolly mammoths

Taking these things in mind, there are some climate-related clues that give us a closer look at the environmental side of migration. Climate models have been used to show that freshwater fluxes linked to surges of ice sheets into the North Atlantic (called Heinrich events) could lead to sudden changes in climate. These events certainly occurred every now and then during the last glacial cycle and may have made large swathes of North, East, and West Africa unsuitable for human occupation, as conditions became very arid. This could have been a push factor in Homo sapiens ' migration out of Africa.

There was the slight problem of the Sahara standing between Homo sapiens and a possible way out, however. Other climate studies have shown, though, that there were 'wet' or 'green' phases during which more friendly corridors would have opened to form pathways across the Sahara, the timing of which seem to coincide with the major dispersal of humans leaving sub-Saharan Africa (identified wet periods are between roughly 50,000 - c. 45,000 years ago and c. 120,000 - c. 110,000 years ago). However, a recent study has shown that although the 'wet' phase holds up for Sapiens ' early migration into the Levant and Arabia between roughly 120,000-90,000 years ago, during the time of the main migration (around 55,000 years ago) the Horn of Africa was actually really dry, arid, and a bit colder. This may, then, have helped push the main wave out.

Another instance in which the impact of the climate on early human migration seems to become visible occurs even earlier.Around 870,000 years ago, temperatures dropped, and both North Africa and eastern Europe became a lot more arid than before. This may have caused large herbivores to migrate into southern European refuges, with early humans following hard on their tails. At the same time, the Po Valley in northern Italy first opened up and formed a pathway for possible migration into southern France and beyond. This ties in pretty well with Homo heidelbergensis making its way into Europe. Following herds of large herbivores would have been a good strategy in the challenging process of migration, anyway, and a 2016 CE study suggests Homo erectus may also have done this, while also sticking close to flint deposits and avoiding areas with loads of carnivores, at least early on in their dispersal.

Whatever the exact driving forces or the exact difficulties early humans ran into en route, as time passed adaptability reigned supreme and humans – starting with Homo erectus and culminating in Homo sapiens ' greedy dispersal - spread across the whole wide world.

BLIND SPOTS

There are obviously a lot of holes in this story, though, and it cannot hurt to explicitly name some of the blind spots we have to take into consideration at this point in time. As a whole, the dates mentioned above are only our best estimates based on our interpretation of the data we have gathered so far. Some areas in which the story can be fleshed out a lot more if we can get our hands on more evidence are found below.

The Denisovans, for instance, are known to us only through one finger bone and a tooth found in a cave in Siberia, and through their DNA (their genome was sequenced in 2010 CE) which seems to imply they ranged from there all the way to Southeast Asia. It is moreover possible that they interbred with an unknown archaic human, which would obviously tell a story of its own. Fossils of these mysterious humans would be very welcome in trying to fill in the picture of their life and their movement. Another enigmatic species is Homo floresiensis ; exactly how and when did they get to the island of Flores (and did they somehow use boats at this very early point in time)? Who were their ancestors? More evidence is required to seal the deal on this.

Bering Land Bridge Natural Preserve

Another area that keeps researchers and scientists entertained is the Americas. Exactly via which route the Americas were reached and when is something still subject to some strife. Although arrival dates seem to fall somewhere roughly around the 15,000 years ago mark (with a lot of bickering back and forth about the exact thousands of years), a very recent study (Holen 2017) even argues that an early human species may have been in California an astonishing 130,000 years ago; based on what the researchers see as hammer stones and anvils that they argue must have been made by humans (despite the absence of human fossils at the site).

More evidence is clearly needed before this can overwrite the current story regarding the Americas, but it forms a good example of what could happen to our current image of early human migration as new discoveries are made. We certainly cannot paint a complete and finished picture yet.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License