Ancestor Worship in Ancient China › Alaric › Alboin » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Ancestor Worship in Ancient China › Origins

- Alaric › Who was

- Alboin › Who was

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Ancestor Worship in Ancient China › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

Ancestor worship in ancient China dates back to the Neolithic period, and it would prove to be the most popular and enduring Chinese religious practice, lasting well into modern times. The family was always an important concept in Chinese society and government, and it was maintained by the twin pillars of filial piety and respect for one's dead ancestors. The practice of regularly paying homage to one's deceased relatives was further supported by the ever-popular principles of Confucianism which stressed the importance of family relations.

ORIGINS & IMMORTALITY

The earliest evidence of ancestor worship in China dates to the Yangshao society which existed in the Shaanxi Province area before spreading to parts of northern and central China during the Neolithic period (c. 6000 to c. 1000 BCE in this case). In the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 - 1046 BCE) the ancestors of the royal family were thought to reside in heaven within the feudal hierarchy of other spirit-gods. These ancestors, it was believed, could be contacted via a shaman. In the Zhou period (1046 - 256 BCE), the ancestors of rulers had their own dedicated temples, typically within the royal palace complexes, and the presence of such a temple was even a definition of a capital city in the 4th century BCE.

Hungry Ghosts Festival

According to ancient beliefs, each person had a spirit which required the offering of sacrifices, not just royal figures. It was thought that an individual had two souls. After death, one of these souls, the po, rose to heaven while the other one, the hun, remained in the body of the deceased. It was this second soul that required regular offerings of nourishment. Eventually, the hun soul would migrate to the fabled Yellow Springs of the afterlife, but until that time, if the family did not want the spirit of their dead relation to trouble them as a wandering hungry ghost, they had to take certain precautions. The first was to bury the dead with all the essential daily objects (or models of them) they would need in the next life from food to tools. Next, to ensure the corpse remained at peace, it was necessary to offer appropriate and regular offerings.

There was then an ancient belief in the mutually beneficial connection between the living and dead, as here explained by the historian R. Dawson:

Ancestor worship was seen by the mass of the people as a reciprocal arrangement between the dead and the living, in which the latter looked after the supposed physical needs of the former, while in return the ancestors benignly participated in the affairs of the living, receiving news of important events such as births and betrothals, and advising and conferring benefits upon their descendants. They were still thought of as part of the family in the same way as the bureaucratically organised gods of the popular religion were an extension of the political order reigning on earth. (154)

A further dimension of immortality in China was the idea of shou or longevity. Not only did this mean while alive but also in death. Remembering the dead and reverently treasuring their name perpetuated the person's shou. A name could be thus remembered by maintaining a shrine and making offerings to the deceased but another effective method was via literature.Particularly from the Han period (206 BCE - 220 CE), poems and texts were composed to honour dead family members and perpetuate both their name and deeds. One Han dynasty poem has this to say on the subject of remembrance:

Prosperity and decline each has its season,

I grieve that I did not make a name for myself earlier.

Human life lacks the permanence of metal and stone.

How could we lengthen its years?

We suddenly transform, in the way of all matter,

but a glorious name is a lasting treasure.

(Lewis, 175)

SHRINES & SACRIFICES

Ancestor worship began with a son's filial piety for his father while still alive. When the father died the son was expected to follow certain conventions, known as the "Five Degrees of Mourning Attire", as here explained by the historian ME Lewis:

If a son mourned his father, he wore the most humble clothes (an unhemmed, coarse hemp garment) for the longest time (into the third year following death). If he mourned a paternal great grandfather's brother's wife, then he wore the least humble clothing (the finest hemp) for the shortest time (three months). (175)

At the public grave of the deceased, an inscribed stone stele was set up to commemorate the lost family member in name and deed. One example inscription reads thus,

By engraving the stone and erecting this stele, the inscription of merit is made vastly illustrious. It will be radiant for a hundred thousand years, never to be extinguished…Establishing one's words so that they do not decay is what our ancestors treasured. Recording one's name on metal and stone hands it down to infinity. (Lewis, 177)

The emperors, perhaps unsurprisingly, had the grandest shrines dedicated to their ancestors and especially so for the founder of the dynasty. The Founder of the Han dynasty, Emperor Gaozu, had his own ancestral shrine in every commandery across the empire, and by 40 BCE there were 176 such shrines in the capital and another 167 in the provinces. These shrines required a combined staff of over 67,000 and received almost 25,000 offerings each year before their eventual reduction. The move to reduce the imperial shrines may have been an economic necessity but it also helped reinforce the idea that the reigning emperor, with his Mandate of Heaven, was the Son of Heaven and so now more important than his dead predecessors.

Offerings were regularly made at the family cemetery, temple, or shrine. These took the form of food and drink, or the burning of incense, and were carried out on significant dates such as New Year's Day. For imperial ancestors, there were more extravagant ceremonies involving musicians and dancers, and gifts, too, of precious goods and engraved bronze vases, as well as the more sober religious offerings.

Another group of ancestors who received particular worship were those founders of and deceased senior figures belonging to clans. Family groups of this kind were so integral to the functioning of Chinese society that the elders were given legally-recognised powers and responsibilities by the state. These extended family groups shared the same surname in rural villages and together saw that the ancestral graves of the clan, which were located together in the family cemetery, were tended and offered the appropriate sacrifices. A family group might even have its own temple where two or three large ceremonies were held annually and the collective achievements of the clan were celebrated.

THE OFFERINGS MADE TO ANCESTORS WERE DEVOTED TO THE SENIOR MALES OF THE PREVIOUS THREE GENERATIONS WHO WERE NO LONGER LIVING.

Sacrifices were made at the family shrine of more modest individuals by the head of the extended family, usually the most senior living male. This was another motivation besides economics for parents to wish for male offspring as only they could ensure the continuance of ancestral ritual and, in their own person, ensure the survival of the family name. The offerings made to ancestors were devoted to the senior males of the previous three generations who were no longer living. For emperors, the last four generations were venerated, and for all groups, the founder of the family was perpetually remembered by rituals and offerings. The shrine or temple for aristocratic families was either separate from or part of the family home.

The home of ordinary citizens had a dedicated room where inscribed wooden tablets were set up which recorded the names, genealogies, and achievements of the most important male and some female ancestors. Where there was more than one son, the elder son would keep the tablets in his home. As only three generations of ancestors were generally worshipped, the oldest tablets were periodically taken and burned or buried at the grave site of the individual mentioned on the tablet. If the tablets belonged to a clan important enough to have its own ancestral temple, then they were taken there for safekeeping.These tablets were also important in wedding ceremonies where the bride bowed in respect before them to indicate her joining not only a new living family but also a new dead one.

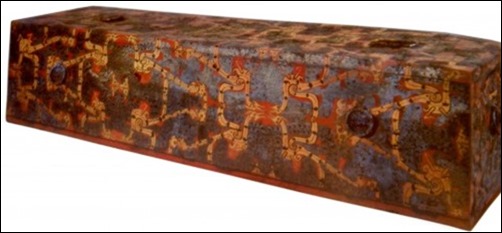

Chinese Lacquered Coffin

Although ancestors were revered that is not to say that the ancient Chinese were obsessed by the dead. On the contrary, examples abound in literature of the necessity for the living to go on living and the dead to rest in peace, as in this Han text from a tomb at Cangshan:

In joy they do not remember one another,

In bitterness they do not long for one another.

(Lewis, 193)

Better, then, to heed the advice of this Han poem, one of the Nineteen Old Poems :

Through the ages mourners in their turn are mourned,

Neither sage nor worthy can escape.

Seeking by diet to obtain immortality,

Many have been the dupes of drugs.

Better far to drink good wine,

And clothe our bodies in silk and satin.

(Lewis, 205)

CHALLENGES TO ANCESTOR WORSHIP

Ancestor worship was not without its challenges throughout China's history, despite its dominance in rural communities and strong traditional appeal. Buddhism, when introduced into China, preached a more spiritual approach than Confucianism and monks, withdrawn from the world and family life, were perhaps not the best advocates of filial piety. Nevertheless, Buddhism did expound a general belief in the advantages of keeping the memory of lost family members as the faith did preach a respect for all people, not just one's parents and family. Buddhist leaders also, no doubt, realised that such a long-practised tradition was unlikely to be driven out of society very easily. Thus, it was not uncommon for Buddhist monks to actively participate in rituals of ancestor worship.

Ancestor worship was practised into more modern times but did face graver interference as time went on, notably from Christian missionaries from the 17th century CE onwards. The Catholic Church and other Christian bodies had originally tolerated the ritual as a social phenomenon rather than a religious one, but an edict by the Vatican in 1692 CE sought to ban them. Naturally, the Chinese authorities did not take kindly to this presumptuous attitude, and the practice of ancestor worship continued much as before.

Alaric › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Donald L. Wasson

Alaric I (reigned 394-410 CE) was a Gothic military commander who is famous for sacking Rome in 410 CE, which was the first time the city had been sacked in over 800 years. Although little of his family is known, we do know that he became the chief of the Tervingi and Greuthungi tribes (later known as the Visigoth and Ostrogoth, respectively). He led his fellow Gothson a rampage through the Balkans and into Italy, sacking the Roman capital, and then moving further south and dying soon after in 410 CE. After Alaric's death, his brother-in-law Athaulf led the Goths into Gaul.

ALARIC COMES TO POWER

For centuries the people of Rome lived comfortably behind the walls of their city. The empire was continually expanding, and the army, under a long series of capable military commanders, kept the dreaded barbarians safely away from the city's gates.Unfortunately, the supremacy of Rome began to slowly decay when the empire was split into two by Diocletian, and the power base gradually moved to Constantinople and to the emperor who resided there. This shift in political and economic power left Rome weak and vulnerable. A young, former Roman commander took advantage of this situation and sacked the once eternal city: his name was Alaric.

Although labelled as a barbarian, Alaric was a Christian who received his military training in the Roman army. He commanded the Gothic allies, fighting alongside the Romans at the battle of River Frigidus in 394 CE, a battle waged between the eastern emperor Theodosius I and the western usurper emperor Eugenius. Shortly after the battle, in 395 CE, Emperor Theodosius, the last to unite and rule both halves of the empire, died. The empire was again divided. Alaric's nemesis (and later ally) the ambitious Flavius Stilicho (359-408 CE) became regent (or at least claimed to be) for the former emperor's two sons, Arcadius and Honorius (395–423 CE). Arcadius became emperor in the east (dying in 408 CE), while the younger Honorius would eventually assume the throne in the west.

ALARIC & STILICHO

WHEN THE SALARIAN GATE WAS OPENED BY AN UNNAMED SYMPATHIZER, AN ARMY OF “BARBARIANS” LED BY ALARIC ENTERED ROME, AND A THREE DAY PILLAGE BEGAN.

Stilicho, magister militum or commander-in-chief (and son of a Roman mother and Vandal father), clashed with Alaric. This conflict stemmed from a treaty signed in 382 CE between the Romans and the Goths, after the Gothic War, which allowed them to settle in the Balkans but only as allies, not citizens. The treaty further required them to serve in the Roman army, something that alarmed many of the Goths. And, as they had feared, their extensive losses at Frigidus validated their concern;they had been placed on the front lines, ahead of the regular Roman army, as "sacrificial lambs".

Alaric lived under the mistaken delusion that the Roman government in the west was stable and would last forever, providing security for his people. In an attempt to force a rewrite of the treaty, Alaric and his army took advantage of the growing tension between the east and west and ransacked cities throughout the Balkans and into Greece, eventually invading Italy in 402 CE.He demanded not only grain for his people but also recognition as citizens of the empire, as well as his appointment as magister militum, an equal in the Roman army; Stilicho vehemently refused these demands. Although Alaric was forced to retreat at Verona, in 406 CE an attempt was made for compromise. Through his agent, Jovius, the Roman commander listened to Alaric's demand of legal rights to their land with annual payments of gold and grain. In return, Alaric was to assist Stilicho in his plan to invade the east; with Arcadius in full power in the east, Stilicho had already secured himself in the west (he had married his daughter to Emperor Honorius), and with the help of Alaric, he would attack the east, dethroning Arcadius.

The deal would never come to pass. Alaric sat patiently, waiting for Stilicho to join him. Despite his good intentions, Stilicho, however, was delayed due to problems elsewhere in the west: the Gothic king Radagaisus invaded Italy; the Vandals, Alans, and Survi invaded Gaul; and the future emperor Constantine III (a viable threat to the throne) emerged victorious from Britain. These setbacks made money scarce and negotiations impossible. Alaric's patience wore thin, and his demand for 4,000 pounds of gold (payment for his waiting) went unheard. As a result, he began to slowly move his army closer to Italy. Although Stilicho wanted to pay the demands, the Roman senate, under the leadership of a war hawk named Olympius disagreed, and the senate considered Alaric's actions a declaration of war.

With Olympius' urging, the emperor decided to invade the east. Stilicho warned against the emperor leading the army, choosing to lead an army himself. With Stilicho away, Honorius and Olympius traveled to Ticinum, an Italian city just south of Milan, supposedly to review the troops; however, Olympius, without the permission of the emperor, ordered the killing of thousands of Gothic allies - an action that further angered Alaric. A final fatality of this massacre was Stilicho himself, who was accused of plotting with Alaric. As a result of this treachery, over 10,000 soldiers defected and joined Alaric's army. In 408 CE the Gothic army sacked the cities of Aquilea, Concordia, Altinum, Cremona, Bononia, Ariminum, and Picenum, choosing, however, to avoid Ravenna, the capital of the western empire and home of Emperor Honorius. Instead, Alaric set his sights on Rome, surrounding all thirteen gates of the city, blockading the Tiber River and forcing widespread rationing; within weeks decaying corpses littered the city streets.

ALARIC & THE SACKING OF ROME

As additional forces came to Alaric's side, Emperor Honorius did little to help the city and oppose Alaric. The Goths were still viewed as barbarians and no match for the armies of the empire. Although the treasury was virtually empty, the senate finally succumbed, and wagons left the city carrying two tons of gold, thirteen tons of silver, 4,000 silk tunics, 3,000 fleeces, and 3,000 pounds of pepper. Alaric eased the siege, still hoping to negotiate terms, but Honorius remained blind to the seriousness of the situation. While temporarily agreeing to Alaric's demands - something he never intended to honor - 6,000 Roman soldiers were sent to the city but were quickly defeated by Alaric's brother-in-law Athaulf.

Sack of Rome by the Visigoths

Realizing further negotiations were impossible, especially after an ambush from the Roman commander Sarus, Alaric returned to the gates of Rome. He had tried everything, even attempting to name a sympathetic senator named Attalus appointed as a new emperor failed. He took Honorius's sister Galla Placidia as hostage but to no avail. An alliance asking for an annual payment of gold and grain, as well as the provinces of Venetia, Noricum, and Dalmatia, was refused. Alaric had few choices left, and on August 24, 410 CE, Alaric prepared to enter the city; Rome had not been sacked since 390 BCE. When the Salarian Gate was opened by an unnamed sympathizer, an army of “barbarians” entered Rome, and a three day pillage began. While the homes of the wealthy were plundered, buildings burned, and pagan temples destroyed, St. Peter's and St. Paul ’s were left untouched. Oddly, when Honorius heard that Rome was perishing, he feared the worst - not because of his love of the city, but because he believed his beloved fighting cock named Rome had been killed.

Alaric left the city, intending to move into Sicily and later Africa. Unfortunately, he never realized his dream and died soon after in 410 CE. Athaulf assumed control of the army, eventually leading the Goths into Gaul. Alaric had made every attempt to secure a home for his fellow Goths: the sack of Rome was his final hope. The city would never recover. The burning of Rome was, according to pagan interpretation, the result of the city becoming Christian. Others viewed Rome as a symbol of the past;the new center of the empire was Constantinople. In 476 CE, 66 years after Alaric, the city finally fell to Odoacer, spelling the end to the empire in the west.

Alboin › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Alboin (reigned 560-572 CE) was a king of the Lombards who led his people into Italy and founded the Kingdom of the Lombards which lasted from 568-774 CE. His father was Audoin, King of the Lombards, and his mother the Queen Rodelinda.He was most likely born c. 530 CE in Pannonia, grew up with military training, and fought against the Avar and Gepid tribes before leading his people to Italy. After his first wife, Chlothsind, died, he married Rosamund, the daughter of the Gepid king Cunimund whom Alboin killed in battle. In spite of his military victories and successful reign, he came to be known to later generations primarily through his assassination by his wife, which formed the basis of paintings by a number of artists and works such as the opera Rosamunda by Giovanni Rucellai (1525 CE) and the verse drama Rosamund by Algernon Charles Swinburne (1860 CE). Both of these artists drew heavily from the primary work on Alboin: Paul the Deacon's 8th century CE History of the Lombards. Paul records that, in 572 CE, after Alboin had ruled Italy for almost four years, Rosamund had him assassinated to avenge her father's murder. The dramatic nature of the assassination, and Alboin's treatment of Rosamund in their marriage, has leant itself to imaginative works in which either Alboin or Rosamund is depicted as a tragic figure who suffers unjustly. According to the primary sources, however (especially that of Paul the Deacon), Alboin was a tribal warlord who established a homeland for his people and treated his captive wife as he would any other war prize; he paid for such unkind treatment with his life.

MILITARY VICTORIES & REIGN IN PANNONIA

Nothing is known of Alboin's early years or upbringing. His later exploits suggest that he had military training and, as the son of the king, was most likely instructed in politics. Paul the Deacon first records that he succeeded his father, Audoin, in 560 CE.Audoin had allied himself with the Byzantine Empire, but either he or Alboin decided to broaden their power base by also allying themselves with the Franks, who were then growing in power. In c. 560 CE, therefore, Alboin married the daughter of the Frankish king Chlothar, Chlothsind, to secure this alliance. The historian Francesco Borri writes:

Alboin must have been a very powerful man, even if contemporary sources describing his political and military activities are scanty...The fact that Alboin was able to marry a Frankish princess, which no Lombard king after him was able to do, confirms his importance in the scenario of late Roman Europe (223-224).

The Lombards may have been invited into Pannonia by the Byzantine Empire to deal with the threat of the Gepid tribes in the region or may have come on their own. Either way, conflicts between the Lombards and the Gepids were routine, and the Lombards allied themselves with another tribe, the Avars, to finally crush the Gepids. The Avars had also come to Pannonia either by the invitation of Emperor Justin II or on their own initiative. The Avar king Bayan I (reigned 562/565-602 CE) brokered a deal with Alboin agreeing that, if their alliance defeated the Gepids, the Avars would be given the Gepid's lands.According to Paul the Deacon, in 567 CE the Gepids, now under the rule of their king Cunimund, attacked the Lombards (though other sources claim Alboin and Bayan I instigated hostilities). The precise dates of the alliances between the Byzantine Empire, the Lombards, the Avars, and the Gepids are confused owing to constant contradictions in the primary sources, but it appears that, at this time, the Lombards and Avars were closely allied against the Gepids with the support of the Byzantine Empire. The alliance crushed the Gepids, and Alboin killed Cunimund by beheading him in battle. He took the head of the king as a trophy and later had it made into a wine cup which he wore on his belt. Other sources, however, claim it was Bayan I who killed Cunimund, beheaded him, and gave the skull to Alboin to celebrate their joint victory.

BY 572 CE ROSAMUND COULD NO LONGER TOLERATE BEING MARRIED TO THE MAN WHO HAD KILLED HER FATHER AND WORE HIS SKULL ON HIS BELT AS A DRINKING CUP.

With the Gepids defeated, Alboin consolidated his rule and marked the boundaries of his territory. The Avars, however, had managed to occupy more of the region than the Gepids had before them, owing to the deal Alboin had agreed to before battle, and threatened the Lombard territories. Alboin then married Rosamund, daughter of Cunimund, to form an alliance with the Gepids against the Avars, but it was too late. The Avars under Bayan I were too powerful now, and the Gepid forces were too weakened by the previous war to prove very useful. Alboin realized the most prudent course of action was to leave Pannonia, but he was uncertain where to lead his people to. A large number of Lombard troops had served in the imperial forces under the Byzantine general Narses in Italy, performing particularly well in combat at the Battle of Taginae in 552 CE where Narses defeated the Ostrogothic king Totila and re-claimed Italy for the empire. These soldiers still remembered Italy as a fertile land, and either they suggested a migration to Alboin or, according to other sources, Narses himself invited them to Italy (this later claim is routinely contested). Whatever his motivation, in April of 568 CE, Alboin led the Lombards out of Pannonia and into northern Italy.

MIGRATION TO ITALY & REIGN

The Byzantine Empire were at war with the Ostrogoths of Italy since the death of Theodoric the Great in 526 CE until Narses' victory over the Goths at the Battle of Mons Lactarius in 555 CE. In 568 CE, Italy was therefore a part of the Byzantine Empire but was sparsely fortified or defended. So many resources had been expended in winning it back from the Goths over so many years that now the empire seemed confident, for some reason, that the region could defend itself if need be. Alboin and his people entered Italy from the north and took the town of Forum Iulii without a fight. From here, he marched on Aquileia and, with that town secure, continued his conquest of the region until, by 569 CE, he had taken Milan and controlled the north of Italy without engaging in any serious military conflicts. Between 569-572 CE, Alboin conquered most of the rest of the country (though some parts were still controlled by the Byzantine Empire, such as Rome ), establishing his capital at Verona while he lay siege to Pavia, the only city that resisted the Lombard invasion to any significant degree. It took three years of siege to take the city and, while that was in progress, Alboin set about establishing his kingdom from his palace at Verona.

Alboin from the Nuremberg Chronicle

He divided the country into 36 territories known as "duchies," presided over by a duke who was responsible for reporting directly to the king. While this made for efficient government from a bureaucratic point of view, it left too much power in the hands of the individual dukes, and so regions either prospered or suffered depending on the quality of their particular duke.Alboin ruled effectively from Verona but, as he was more concerned with securing his borders against the Franks and fending off the eastern empire's efforts to dislodge him, he left the affairs of government to these subordinates, which resulted in a lack of cohesion between the territories as each duke, naturally, wanted the best for his particular region. These dukes, therefore, acted autonomously in conquering regions towards the south of Italy which, scholars claim, Alboin had no interest in taking from the Byzantine Empire.

The sources on Alboin's reign are few. Paul the Deacon writes how, under Alboin's reign, "There was this wonderful kingdom of the Lombards. There was no violence, no plotting pitfalls, and no others unjustly oppressed. No one plundered and there were no thefts, there was no robbery; everyone went wherever they wanted, safe and without any fear" (History, III, 16).Although this description is considered by scholars to be an exaggeration, it does seem that Alboin's reign brought stability and prosperity to Italy, especially in the north, and he was an effective monarch in spite of the activities of the individual dukes.Although they acted in their own best interests, historians surmise (based on the general reaction to Alboin's death and the aftermath) that they seem to have believed they were pursuing a course Alboin would have approved of.

ASSASSINATION & AFTERMATH

Alboin's marriage to Rosamund had never been a happy one. Paul the Deacon claims that Alboin routinely abused his wife and mocked her. The marriage, like many involving nobility through the ages, had been simply a device to secure an alliance.Further, Rosamund was already Alboin's captive after the defeat and death of Cunimund, and so she hardly had a choice in marrying the Lombard king. In June of 572 CE, she apparently reached the point where she could no longer tolerate being married to the man who had killed her father and wore his skull on his belt as a drinking cup. Paul writes:

When he [Alboin] was more flown with wine than was appropriate at a feast in Verona, he asked that wine be given to the queen to drink in the cup which he had made from the head of his father-in-law Cunimundus. He invited her to drink happily with her father...Therefore, when Rosamund found out about the matter, she conceived a deep pain in her heart that she was unable to quell. She burned to avenge the death of her father on her husband (History, III, 18).

Rosamund convinced Alboin's foster brother, Helmechis, to murder him. Other sources on Alboin's assassination (such as Gregory of Tours or Marius of Aventicum) provide different details, but all agree that the plot was set in motion by Rosamund who had, perhaps, fallen in love with Helmechis or, at least, was having an affair with him. Rosamund and Helmechis enlisted the aid of a bodyguard named Peredeo, who was tricked into the conspiracy by Rosamund who disguised herself as a servant, had sex with him, and then essentially blackmailed him into service. One day, when Alboin had retired to his room to rest after lunch, Helmechis and Peredeo attacked him. Rosamund had ordered that Peredeo tie Alboin's sword to his bed so the king would be unarmed. Alboin fought off his assailants with a footstool but was beaten down and killed.

Alboin and Rosamunde

The couple, along with Alboin's daughter from his first marriage, Peredeo, the royal treasure, and a segment of the army, then fled from Verona to the Byzantine-controlled city of Ravenna. This course of action has suggested to many historians that the assassination was actually instigated by the Byzantine Empire and Rosamund was manipulated by them. While the empire may have had a hand in Alboin's death (and certainly would have been relieved by it), the primary sources all claim the assassination was planned and carried out by Rosamund to avenge her father's death and punish her husband for his abuse of her. Even so, the fact that the conspirators were welcomed in Ravenna and that, after their deaths, the royal treasure and Alboin's daughter were sent to Constantinople, does argue in favor of Byzantine involvement in Alboin's assassination.

Helmechis and Rosamund were married in Ravenna, and he proclaimed himself king. The dukes refused to acknowledge him, however, and proclaimed their own king, Cleph, the duke of Pavia, which city had finally fallen to the siege. Rosamund, apparently, did not find Helmechis any more to her liking than she had Alboin and poisoned his wine cup. Helmechis, however, suspecting her treachery, made her drink from the cup either before, or just after, he had done so, and in this way they both died at the other's hands.

Cleph reigned for 18 months before he was assassinated by one of his servants. The individual dukes then fought each other for control of the kingdom from 572-586 CE,when King Authari was elected in order to fight off incursions by the Byzantines and the Franks. The Lombard Kingdom in Italy maintained its control of the region, sometimes losing and sometimes substantially gaining territory, until 774 CE, when they were conquered by Charlemagne of the Franks and absorbed into his empire. Although later Lombard kings, such as Agilulf (reigned 590-616 CE), Rothari (reigned 636-652 CE) and, especially, Liutprand (reigned 712-744 CE), made greater advancements in conquest and government than Alboin, the first Lombard king of Italy is still remembered for leading his people to a secure homeland and establishing a kingdom he felt they could call their own. His life and achievements have been overshadowed by his death and his subsequent transformation into a character in literary tragedy but, while he lived, he seems to have been a man of considerable power and vision for the future of his people.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License