Antiochia ad Cragum › Antipater › Trade in Ancient Egypt » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Antiochia ad Cragum › Origins

- Antipater › Who was

- Trade in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Antiochia ad Cragum › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Jenni Irving

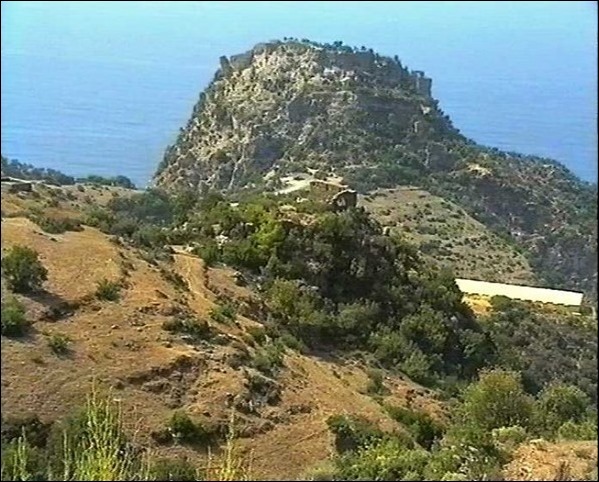

Located in Cilicia in Anatolia, Antiochia ad Cragum has also been called Antiochetta and Antiohia Parva which basically translate to 'little Antiochia '. Its name 'Cragum' comes from its position on the Cragus mountain overlooking the coast. It is located in the area of modern Guney about 12 km from the modern city of Gazipasa. The city was officially founded by Antiochis IV around 170 BCE when he came to rule over Rough Cilicia. The site covers an area of around three hectares and contains the remains of baths, market places, colonnaded streets with a gateway, an early Christian basilica, monumental tombs, a temple and several structures which are yet to be identified. Excavations are currently being undertaken by the Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project headed by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

ANTIOCHIA AD CRAGUM & ITS HARBOUR LIKELY SERVED AS ONE OF THE MANY HAVENS FOR CILICIAN PIRATES ALONG THE SOUTH ANATOLIAN COAST.

The site and its harbour likely served as one of the many havens for Cilician pirates along the South Anatolian coast, likely because of its small coves and hidden inlets. Unfortunately no definite pirate remains are visible in the modern day. Its pirate past ended with Pompey ’s victory in the first century BCE and the take over by Antiochis IV. Initial occupation appears to have occurred in the Classical and Hellenistic periods followed by a surge of activity in these Roman periods. The city itself was built on the sloping ground that comes down from the Taurus mountain range which terminates at the shore creating steep cliffs; in some places several hundred metres high. The temple complex is situated on the highest point of the city and most of the building material remains though in a collapsed state. There is also evidence of a gymnasium complex nearby.

The harbour at Antiochia ad Cragum measures about 250,000 square metres and is one of the few large, safe harbours along the coast between Alanya and Selinus. On its Eastern side are two small coves suitable for one or two ships but with limited opportunity for shipping and fishing due to wave activities. The area is well situated as a defensible position against invaders.Recent Terrestrial survey at Antiochia ad Cragum has had emphasis on finding evidence of pirate activity which has been limited, but it has turned up pottery principally from the Byzantine period with additional pottery from the late Bronze Age, the Hellenistic and some from the Roman periods. There is little evidence of pre-Roman occupation at the fortress or pirate's cove at Antiochia ad Cragum. Banana terracing may have caused much of the evidence to have been erased. The maritime survey has turned up shipping jars, transport Amphoraes and anchors from the Byzantine, Roman and Hellenistic periods as well as a range of miscellaneous items. The assemblage appears to indicate early activity to the West of the harbour moving East over time.

Antipater › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Donald L. Wasson

Antipater (c. 399-319 BCE) was a Macedonian statesman and loyal lieutenant of both Alexander the Great and his father Philip II of Macedon. As a regent in Alexander 's absence, Antipater subdued rebellions and mollified uprisings, proving his unwavering loyalty for more than a decade. Unfortunately, a serious disagreement between the two led to a once trusted commander being implicated in the suspected poisoning of one of history's greatest leaders.

EARLY CAREER

Antipater had always been considered a trustworthy commander, representing Philip at Athens in 346 BCE. Following the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE, he was entrusted with the task of accompanying the young Alexander in taking the ashes of fallen Athenians killed in battle to the city. After Philip's assassination by the disgruntled Pausanias, a disagreement arose among the nobility as to who was the rightful heir to the throne of Macedon. At a meeting presided by Antipater, several nobles voiced support for Amyntas, the son of Philip's brother Perdiccas. Some of these men disliked Alexander only because his mother was not a true Macedonian. However, Antipater and fellow commander Parmenio, who was in Asia Minorat the time, remained loyal to Alexander, so with the urging of his doting mother, Olympias, Alexander became king at the age of twenty.

The first few years of his reign were not easy for the young king. Following his father's death, Alexander found not only his ability but also the strength of Macedon's control over Greece threatened. While the young king and his army traveled northward to secure Thrace in 335 BCE, Antipater remained in Macedon, serving as his deputy. While in Thrace, word of Alexander's supposed death made its way to the Greek city of Thebes and they revolted. When they heard of the approaching the Macedonian army, they assumed, incorrectly, that it was under the command of Antipater. Wrong! It was Alexander, and the city would suffer. The rest of Greek city-states - except for Sparta - quickly realized the true strength of Alexander and submitted willingly to his leadership.

ALEXANDER'S REGENT

Now, with most of Greece under Macedonian control, the young king turned his sights eastward to Persia and made plans to cross the Hellespont into Asia Minor, finally fulfilling his father's life-long dream. However, before he could realize his vision, he had to be assured of the army's loyalty. Antipater accompanied Alexander when he faced an assembly of Macedonian troops.Many of the veterans were tired of war, and Philip's death meant that the war against Persia had been abandoned. As the young king stood before them and cried, he promised each of them glory and riches. To a man they swore their loyalty. Both Antipater and Parmenio, however, urged Alexander to reconsider and wait until an heir was born to secure the throne. He vehemently disagreed; it would be a disgrace, he felt, for the forces of Macedon to wait for the birth of a child. To maintain authority in his absence, he left Greece and his beloved Macedon in the capable hands of Antipater as hegemon. In 334 BCE Alexander gathered his forces and crossed into Asia Minor. The young king would never return.

Alexander the Great

Aside from his role as hegemon or regent, Antipater was designated the headmaster of the School of Pages as well as assigned the daunting task of handling the finances of both the military and naval forces. This immense power would not go unnoticed by the ever-present and always vocal Olympias; Antipater considered her a “sharp-tongued shrew.” Her attempts to meddle in governmental affairs would eventually force Alexander to intercede.

Luckily, however, Antipater was not left alone for he had an army of 12,000 phalangites, 1,000 Companion cavalry, five hundred light-armed cavalry, and the power to summon the militia of the Greek city-states. Despite the constant demand for reinforcements, Antipater was able to amass a total of over 40,000 infantry and cavalry, and he would soon need it. Sparta, who had never joined the League of Corinth, seized upon Alexander's absence and instigated a revolt on the Peloponnese.

ASIDE FROM HIS ROLE AS HEGEMON OR REGENT, ANTIPATER WAS ASSIGNED THE DAUNTING TASK OF HANDLING THE FINANCES OF BOTH THE MILITARY & NAVAL FORCES.

In 331 BCE, about the time Alexander was preparing to meet Darius at Gaugamela, King Agis III of Sparta joined with forces from Elis, Arcadia, and Achaea, and declared war on Macedon. The Spartan king had been negotiating secretly with the Persians, seeking their assistance. He had planned to meet Darius's commanders, Autophradates and Pharnabazus on the island of Siphnos to discuss an alliance, but the Persian defeat at Gaugamela ended any further discussion. Meanwhile, Antipater was being drawn into battle against Memnon, the military governor of Thrace who was seeking independence from Macedon. Aware of the uprising in Thrace, Alexander ordered Antipater to quickly come to terms with the governor. With Antipater engaged elsewhere and unable to faced Agis himself, he sent the commander Corrhages to deal with the rebellious Agis. Unfortunately, Corrhages was defeated and killed.

With little alternative, Antipater reached an agreement with Memnon and headed southward. Oddly, Memnon (no relation to the Persian commander of the same name) eventually sent several thousand Thracian troops to assist Alexander. Antipater and Agis met at Megalopolis, a city north of Sparta. The Macedonian commander was victorious, wiping out all Spartan resistance. The defeated Spartan king was carried off the field of battle by his troops, dying from a spear wound. Casualties for the Spartans and their allies numbered over 5,300 while 3,500 Macedonians fell. When Alexander heard of the victory, he considered it insignificant.

CONFLICT WITH OLYMPIAS

Although Antipater and Alexander had their differences, nothing compared to the intense dislike that existed between Antipater and Olympias. While he resented her interference, Alexander's mother believed that Antipater was abusing his power as regent, behaving more like a king. Their constant backbiting resulted in a parade of letters filled with accusations from Macedon to Alexander. Of course, the king was torn between his love for his mother and his respect of Antipater. In his Campaigns of Alexander, historian Arrian wrote, “Indeed, the stories of her behavior gave rise to a much-quoted remark of Alexander's, to the effect, that she was charging him a high price for his nine months lodging in her womb" (368).

Olympias

Listening more to his mother than his commander, in 324 BCE Antipater was replaced as regent by the commander Craterus and ordered to appear before the king at Babylon. Antipater resented the order, considering it a death warrant. Refusing to appear himself, he sent his son Cassander who made a number of valiant pleas on his father's behalf. Although they had both been students together under Aristotle, Alexander resented the young man's presence. The tension between the two increased when Cassander unknowingly laughed at seeing a number of Persians prostrating themselves before the king - an old Persian custom called proskynesis. Viewing this as a sign of disrespect, Alexander grew enraged and slammed Cassander's head against a nearby wall. The incident would haunt him for the remainder of his life. Years later, whenever Cassander saw a statue or painting of Alexander, he would faint. To some the incident would be seen as insignificant, just another outburst by Alexander, if not for what would happen afterwards.

ALEXANDER'S DEATH

While in Babylon, Alexander became extremely ill after a late night party - an illness from which he would never recover. On June 10, 323 BCE, the great Alexander died. A debate as to the cause exists to this day. Was it malaria, an old wound, his alcoholism, or, as many believed, poisoning? Rumors surrounding this latter cause brought the name of Antipater into the discussion. Did he willingly participate in a conspiracy to poison Alexander? Did he order his son Iolaus, the cupbearer to the king, to administer the fatal dose, for was it not Iolaus's lover who had invited the king to the party?

Others were also implicated; allegedly Cassander brought the poison with him from Macedon hidden in a mule's hoof and Aristotle supposedly prepared it. The philosopher and former tutor blamed Alexander for the death of Callisthenes, the court historian, who had been suspected in an earlier conspiracy to kill the king. Not everybody was convinced of these accusations, though.The historian Arrian, who never believed the rumors, wrote,

I am aware that much else has been written about Alexander's death; for instance, that Antipater sent him some medicine which had been tampered with and that he took it, with fatal results. Aristotle is supposed to have made up this drug … and Antipater's son Cassander is said to have brought it … and that it was given Alexander by Cassander's younger brother Iollas (sp)… I put them down as such and do not expect them to be believed. (394 -395)

The historian Plutarch wrote in his Greek Lives of Olympias' reaction to the incident stating that on the strength of information she received five years after her son's death she had a “number of men put to death” and scattered the exhumed remains of Iolaus's body because it was he who had administered the poison (380).

THE LAMIAN WAR

Alexander died without naming an heir or successor. Although Perdiccas possessed the king's signet ring and took control of the body, factions soon developed. While these factions would change over the next three decades, Antipater and his son initially sided with the commanders Ptolemy and Antigonus. When each commander claimed part of Alexander's empire for himself, Antipater took control of Macedon. However, peace at home would not remain for long. Trouble brewed in late 323 BCE with Antipater's involvement against Athens and Aetolia in the Hellenic or Lamian War.

Alexander Sarcophogus

The war was initially caused by Leosthenes, an Athenian who despite being raised in Macedon detested the Macedonians.Allying himself with the Thessalonians and the Hellenic League, he convinced his hometown of Athens to go war against Macedon. The coalition almost defeated Macedon. An excellent commander in his own right, Leosthenes cornered Antipater at Lamia in Thessaly. Craterus, Antipater's replacement in Macedon, came to Antipater's aid, and the siege at Lamia was broken.

In the subsequent battle at Crannon in 322 BCE, the Athenian commander was killed, forcing an end to the war. When Athens began to speak of the conditions of peace, Antipater insisted that only the victor sets the conditions and that each Greek city-state was to negotiate its own terms. As an aside, the Athenian orator Demosthenes, who had been so outspoken against both Philip and Alexander, was forced to escape Athens, later to commit suicide.

DEATH & LEGACY

Antipater died in 319 BCE at the age of eighty. His son Cassander, as always, remained at his side. Unfortunately, Cassander was not named the heir. Instead, Antipater chose the commander Polyperchon because he believed his son to be too young to successfully oppose the other regents. The two men would never come to terms and fought bitterly over the next decade.Eventually, Cassander would take control Macedon and before his own death in 297 BCE would execute not only Alexander's wife Roxanne and son Alexander IV but also the ever-present and always outspoken Olympias.

Trade in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Trade has always been a vital aspect of any civilization whether at the local or international level. However many goods one has, whether as an individual, a community, or a country, there will always be something one lacks and will need to purchase through trade with another. Ancient Egypt was a country rich in many natural resources but still was not self-sufficient and so had to rely on trade for necessary goods and luxuries.

Trade began in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE) and continued through Roman Egypt (30 BCE-646 CE). For most of its history, ancient Egypt's economy operated on a barter system without cash. It was not until the Persian Invasion of 525 BCE that a cash economy was instituted in the country. Prior to this time, trade flourished through an exchange of goods and services based on a standard of value both parties considered fair.

Ancient Egyptian Weight of One Deben

Goods and services were valued on a unit known as a deben. According to historian James C. Thompson, the deben"functioned much as the dollar does in North America today to let customers know the price of things, except that there was no deben coin "

(Egyptian Economy, 1). A deben was "approximately 90 grams of copper ; very expensive items could also be priced in debens of silver or gold with proportionate changes in value" (ibid). If a scroll of papyrus cost one deben, and a pair of sandals were also worth one deben, the pair of sandals could be traded fairly for the papyrus scroll. In this same way, if three jugs of beer cost a deben and a day's work was worth a deben then one would fairly be paid three jugs of beer for one's daily labor.

(Egyptian Economy, 1). A deben was "approximately 90 grams of copper ; very expensive items could also be priced in debens of silver or gold with proportionate changes in value" (ibid). If a scroll of papyrus cost one deben, and a pair of sandals were also worth one deben, the pair of sandals could be traded fairly for the papyrus scroll. In this same way, if three jugs of beer cost a deben and a day's work was worth a deben then one would fairly be paid three jugs of beer for one's daily labor.

FROM LOCAL TO INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Trade began between Upper and Lower Egypt, and between the different districts of those regions, prior to unification c. 3150 BCE. By the time of the First Dynasty of Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2890 BCE) trade was already long established with Mesopotamia. The First Dynasty kings established a strong central government at their capital of Memphis and a bureaucracy soon developed which handled the details of running the country, including trade with neighboring lands.Mesopotamia was an early trade partner whose influence on the development of Egyptian art, religion, and culture has been noted, contested, and debated by many different scholars over the last century. It seems clear, however, that the earlier Mesopotamian culture - especially the Sumerian - had a significant impact on the developing culture of Egypt.

Early Egyptian art, to cite just one example, is evidence of this influence. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson notes that the famous Narmer Palette from the First Dynasty "with its depiction of monsters and entwined long-necked serpents is distinctively Mesopotamian in design" (267). Bunson also notes that knife handles and cylinder seals from Mesopotamia have been found in Egypt dating to about the same period whose designs were used by later Egyptian artisans.

By the time of the First Dynasty, international trade had been initiated with the regions of the Levant, Libya, and Nubia. Egypt had a trading colony in Canaan, a number in Syria, and even more in Nubia. The Egyptians had already graduated from building papyrus reed boats to ships of wood and these were sent regularly to Lebanon for cedar. The overland trade route through the Wadi Hammamat wound from the Nile to the Red Sea, the goods packed and tied to the backs of donkeys.

ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT TRADE CENTERS IN NUBIA IS REFERRED TO IN EGYPTIAN TEXTS AS YAM, A RESOURCE FOR WOOD, IVORY, AND GOLD.

While many of these trade agreements were achieved through peaceful negotiation, some were established by military campaign. The third king of the First Dynasty, Djer (c. 3050-3000 BCE) led an army against Nubia, which secured valuable trade centers. Nubia was rich in gold mines and, in fact, gets its name from the Egyptian word for gold, nub. Later kings would continue to keep a strong Egyptian presence on the border to ensure the safety of the resources and trade routes.Khasekhemwy, the last king of the Second Dynasty of Egypt (c. 2890 - c. 2670 BCE), led campaigns to Nubia to put down rebellions and secure trade centers and his methods became the standard for the kings who came after him.

One of the most important trade centers in Nubia is referred to in Egyptian texts as Yam. During the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) Yam is cited as a resource for wood, ivory, and gold. The precise location of Yam is unknown, but it is thought to have been somewhere in the Shendi Reach area of the Nile in modern-day Sudan.

Yam continued as an important trade center through the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE) but then disappears from the records and is replaced by another called Irem by the time of the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE). The period of the New Kingdom was the time of Egypt's empire when trade was most lucrative and contributed to the wealth necessary to build monuments like the Temple of Karnak, the Colossi of Memnon, and the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut.

Hatshepsut organized the best-known trade expedition to Punt (modern-day Somalia) which brought back boatloads of valuable items, including incense-bearing trees, but this kind of profit from trade was nothing new. The trade initiated during the Old Kingdom of Egypt helped fund the pyramids of Giza and countless other monuments. The difference between Old Kingdom and New Kingdom trade was that the New Kingdom was far more interested in luxury items and, the more they became acquainted with, the more they wanted.

TRADED GOODS

The kinds of goods traded varied from region to region. Egypt had grain in plenty, and would eventually become known as ' Rome 's breadbasket' during the Roman period, but lacked wood, metal, and other precious stones needed for amulets, jewelry, and other ornamentation. Gold was mined by slaves primarily in Nubia and Egypt's neighboring kings often sent letters requesting vast quantities be sent. The journeys to Nubia were not always easy. Yam was located far to the south, and a caravan had to endure threats from bandits, regional rulers, and nature in the form of floods or windstorms.

Hellenic Trade Routes, 300 BCE

The best-documented expeditions to Yam come from the tomb of Harkhuf, governor of Elephantine, who made four journeys there under the reign of Pepi II (2278-2184 BCE). On one journey, he reports, he arrived to find the king had gone off to waragainst another region and had to bring him back, offering him many lavish gifts, in order to secure the items he had been sent for. On Harkhuf's most famous journey he returned with a dancing dwarf, which so excited the young king that he sent word to Harkhuf instructing him to keep the dwarf safe at any cost and hurry him to the palace. The official letter reads, in part:

Come northward to the court immediately; [...] thou shalt bring this dwarf with thee, which thou bringest living, prosperous and healthy from the land of spirits, for the dances of the god, to rejoice and gladden the heart of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Neferkare, who lives forever. When he goes down with thee into the vessel, appoint excellent people, who shall be beside him on each side of the vessel; take care lest he fall into the water.When he sleeps at night appoint excellent people, who shall sleep beside him in his tent, inspect ten times a night. My majesty desires to see this dwarf more than the gifts of Sinai and of Punt. If thou arrivest at court this dwarf being with thee alive, prosperous and healthy, my majesty will do for thee a greater thing than that which was done for the treasurer of the god Burded in the time of Isesi, according to the heart's desire of my majesty to see the dwarf. (Lewis, 36)

The dancing dwarf of Pepi II is only one example of Old Kingdom luxury items. Contrary to the claims of some scholars, trade in Egypt did not progress from practicality to luxury but remained fairly consistent regarding the goods imported and exported.The only reason the New Kingdom is always singled out for its luxury is that Egypt was in direct contact with more countries during this period than earlier; it is not because the New Kingdom was suddenly made aware of luxury goods. There is no question, however, that Egyptian trade in the New Kingdom was more efficient and wide-ranging than in earlier eras and that luxury goods became more available and desirable. Bunson describes Egyptian trade during this period, writing :

Caravans moved through the Libyan desert oases and pack trains were sent into the northern Mediterranean domains. It is believed that Egypt conducted trade in this era with Cyprus, Crete, Cilicia, Ionia, the Aegeanislands, and perhaps even with mainland Greece. Syria remained a popular destination for trading fleets and caravans, where Syrian products were joined with those coming from the regions of the Persian Gulf. The Egyptians received wood, wines, oils, resins, silver, copper, and cattle in exchange for gold, linens, papyrus paper, leather goods, and grains. (268)

Papyrus shipped to Byblos in the Levant was processed into paper, which was then used by people throughout Mesopotamia and neighboring regions. The association of Byblos with book-making, in fact, provides the basis for the English word ' Bible '.Egyptian trade in the Levant was so widely established that later archaeologists believed there were a number of Egyptian colonies there when, actually, their finds only established how popular Egyptian goods were among the people of the region.

TRADE INCENTIVES & PROTECTION

There were no government-sponsored incentives for trade in Egypt because the king owned all the land and whatever it produced; at least, in theory. The king was ordained and sanctified by the gods who had created everything, and served as the mediator between the gods and the people; he, therefore, was recognized as the land's legitimate steward. In reality, however, from the time of the Old Kingdom onward, the priests of the different cults - especially the Cult of Amun - owned large tracts of land which were tax-exempt. Since there was no law prohibiting priests from engaging in trade, and all profit went to the temple instead of the crown, these priests often lived as comfortably as royalty.

For the most part, however, whatever was produced on the farms along the Nile was considered the property of the king and was sent to the capital. Part of this produce was then returned to the people through distribution centers and a part used for trade. Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson writes:

Agricultural produce collected as a government revenue was treated in one of two ways. A certain proportion went directly to state workshops for the manufacture of secondary products - for example, tallow and leather from cattle; pork from pigs; linen from flax; bread, beer, and basketry from grain. Some of these value-added products were then traded and exchanged at a profit, producing further government income; other were redistributed as payment to state employees, thereby funding the court and its projects. The remaining portion of agricultural produce (mostly grain) was put into storage in government granaries, probably located throughout Egypt in important regional centers. Some of the stored grain was used in its raw state to finance court activities, but a significant share was put aside as emergency stock, to be used in the event of a poor harvest to help prevent wide-spread famine. (46)

It was the king's responsibility to care for the people, the land, and maintain the principle of ma'at (harmony). If the land produced abundantly and there was enough food for everyone, as well as surplus, the king was regarded as successful; if not, the priests would intervene to determine what had gone wrong and what steps needed to be taken to regain the good will of the gods.

The Egyptians did not rely solely on supernatural protection in running their country or engaging in foreign trade, however.Armed guards were sent to protect government-sponsored caravans and, during the New Kingdom of Egypt, a police force manned border crossings, collected tolls, protected toll-collectors, and watched over merchants coming and going from citiesand villages. Armed escorts which accompanied caravans were a powerful deterrent against theft. Harkhuf reports how, returning from one of his journeys to Yam, he was stopped by a tribal leader who at first seemed intent on taking his goods but, seeing the size of his armed escort, gave him many fine gifts, including bulls, and guided him on his way.

Silver Ingots from Syria

Theft of goods was a serious loss to the organizer of the expedition, the 'businessman' as it were, not to the merchant who actually engaged in trade. If a merchant were robbed, he would appeal to the authorities of the region he was passing through for justice, but he might not always get what he felt was due. A thief had to be identified as a citizen of that region in order for the ruler to be held responsible, and even then, if the thief managed to get away, the king was under no obligation to compensate the merchant.

This sort of situation is described in detail in the literary work The Report of Wenamun (c. 1090-1075 BCE), which relates the story of Wenamun's adventures in leading a trade expedition to purchase lumber for the ship of Amun. Wenamun is robbed by one of his own people in the port and, when he reports the theft to the ruler, he is told there is nothing to be done because the thief is not a citizen. The prince advises Wenamun to stay a few days while they look for the thief but can do no more.

In Wenamun's case, he makes the best of the situation by simply robbing someone else, but usually, a merchant would return to the agency sponsoring the expedition and explain what happened. If the story was accepted, the robbed merchant was held blameless; if the account seemed false, charges would be brought. Either way, the individual or agency whose goods were involved in the trade suffered the loss, not the person who carried them for transaction. One would not, of course, want to acquire a reputation for losing goods, and so for those merchants not employed in government-sponsored trade, which included a detail of soldiers, hiring armed guards was another cost to be considered in pursuing trade.

Whatever the dangers and expenses, however, there was never a time when trade lagged in Egypt, not even during those periods lacking a strong central government. In the so-called intermediate periods, individual governors of districts played the part of the governmental agency and maintained the necessary relationships and routes which allowed for trade. The Report of Wenamun, although fiction, still represents realistically how trading partnerships worked in the ancient world.

A little after the time Wenamun was written, the Greek city of Naucratis was established in Egypt, which would be the most important trade center in the country, and among the most vital in the Mediterranean region until it was overshadowed by Alexandria. Greece, Egypt, and other nations would trade goods as well as cultural beliefs through cities like Naucratis and the overland and sea routes, and in this way, trade enlarged and elevated every nation which participated in ways far more significant than simple economic exchange.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License