Beer › Apophis » Ancient origins

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Beer › Antique Origins

- Apophis › Who Was

Ancient civilizations › Historical and archaeological sites

Beer › Antique Origins

Definition and Origins

Beer is one of the oldest intoxicating beverages consumed by human beings. Even a cursory survey of history makes clear that, after human beings have taken care of the essential needs of food, shelter, and rudimentary laws for the community, their next immediate concern is developing intoxicants. Evidence of early beer brewing has been confirmed by finds at the Sumerian settlement of Godin Tepe in modern-day Iran going back to between 3500-3100 BCE but intoxicants had already become an integral aspect of daily human life long before. Scholar Jean Bottero writes:

In ancient Mesopotamia, among the oldest `civilized people' in the world, alchoholic beverages were part of the festivities as soon as a simple repast bordered on a feast. Although beer, brewed chiefly from a barley base, remained the `national drink', wine was not uncommon. (84)

Although wine was consumed in Mesopotamia, it never reached the level of popularity that beer maintained for thousands of years. Sumerians loved beer so much they ascribed the creation of it to the gods and beer plays a prominent role in many of the Sumerian myths, among them, Inanna and the God of Wisdom and The Epic of Gilgamesh. The Sumerian Hymn to Ninkasi, written down in 1800 BCE but understood to be much older, is both a praise song to the Sumerian goddess of beer and a recipe for brewing.

MESOPOTAMIAN BEER WAS A THICK, PORRIDGE-LIKE DRINK CONSUMED THROUGH A STRAW & WAS MADE FROM BIPPAR (BARLEY BREAD).

Brewers were female, most likely priestesses of Ninkasi, and early on beer was brewed by women in the home as a supplement to meals. The beer was a thick, porridge-like drink consumed through a straw and was made from bippar (barley bread) which was baked twice and allowed to ferment in a vat. By the year 2050 BCE beer brewing had become commercialized as evidenced by the famous Alulu beer receipt from the city of Ur dated to that time.

THE ORIGIN & DEVELOPMENT OF BEER

It is thought that the craft of brewing beer began in domestic kitchens when grains used for baking bread were left out unattended and began to ferment. Scholars Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, to name only one authority on the subject, write, “alcoholic beverages probably resulted from an accidental discovery during the early hunter-gatherer stage of human prehistory” (Gods,28). While this theory has long been accepted, scholar Stephen Bertman advances another and discusses the long-standing popularity of the drink:

Though bread was basic to the Mesopotamian diet, botanist Jonathan D. Sauer has suggested the making of it may not have been the original incentive for raising barley. Instead, he has argued, the real incentive was beer, first discovered when kernels of barley were found sprouting and fermenting in storage. Whether or not Sauer is right, beer soon became the ancient Mesopotamian's favorite drink. As a Sumerian proverb has it: "He who does not know beer, does not know good." The Babylonians had some 70 varieties, and beer was enjoyed by both gods and humans who, as art shows, drank it from long straws to avoid the barley hulls that tended to float to the surface. (292)

Lapis Lazuli Cylinder Seal of Queen Puabi

The scholar Max Nelson also rejects the claim that brewing beer was discovered accidentally, writing :

Fruits often naturally ferment through the actions of wild yeast and the resultant alcoholic mixtures are often sought out and enjoyed by animals. Pre-agricultural humans in various areas from the Neolithic period on surely similarly sought out such fermenting fruits and probably even collected wild fruits in the hopes that they would have an interesting physical effect (that is, be intoxicating) if left in the open air. (9)

Beer became popular, not only because of the taste and its effects, but because it was healthier to drink than the water of the region. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek details how the waste disposal systems of the cities of Mesopotamia were intricately designed to deposit human and animal waste outside the city walls, and yet that was precisely where the water supply was usually located. Kriwaczek notes how this was "a magnificent engineering achievement but a potential disaster for public health" (83).The best waters were far from the cities but nearby streams could be tapped for water to make beer which was safer to drink because of the fermenting process which involved boiling the water. Kriwaczek continues:

If the watercourses were unsafe, boreholes and wells were no more providers of drinking water, as the saline water-table was too close to the surface. Beer therefore, sterilized by its weak alcohol content, was the safest drink, just as in the western world, as late as Victorian times, it was served at every meal, even in hospitals and orphanages. In ancient Sumer, beer also constituted a proportion of the wages paid to those who had to serve others for their living. (83)

Beer became the drink of choice throughout the region and especially so once it developed into a commercial enterprise. At this point, it seems, the business was taken over by men who recognized how lucrative it could be and women - the traditional brewers - continued on under their supervision. The brew was all hand-crafted, of course, but as it gained in popularity was made in greater quantities and this led to the development of larger-scale breweries. Scholar Gwendolyn Leick comments:

Beer was produced mainly from barley. From the pounded grain, cakes were molded and baked for a short time.These were pounded again, mixed with water, and brought to fermentation. Then the pulp was filtered and the beer stored in large jars. Mesopotamian beer could be kept only for a short time and had to be consumed fresh.The cuneiform texts mention different kinds of beer, such as "strong beer", "fine beer", and "dark beer". Other sorts were produced from emmer or sesame, as well as dates in the Neo-Babylonian Period and later. (33)

Mesopotamian Beer Rations Tablet

The gods were thought to have given beer to humanity and so beer was offered back to them in sacrifice at the temples throughout Mesopotamia. As noted, it was also used to pay wages and was consumed readily at religious festivals, celebrations, and funeral ceremonies. Beer was associated with good times as a drink which made one's heart feel light and allowed one to forget one's problems.

In The Epic of Gilgamesh, for example, the hero, distraught over the death of his friend, sets out on a quest for immortality and the meaning of life. In his travels, he meets the barmaid Siduri who suggests he leave off such lofty aspirations and simply enjoy life while he lives; in short, she tells him to relax and have a beer. Beer was widely enjoyed for a variety of reasons and under virtually every sort of circumstance. Black and Green write:

That commercialized social drinking, not for religious or medicinal purposes, was common by at least the early second millennium BC is attested by the laws of Hammurabi of Babylon regulating public houses. (Gods, 28)

Although the Sumerians had first developed the craft of brewing, the Babylonians took the process further and regulated how it was brewed, served, and even who could sell it. A priestess who had been consecrated to a deity, for example, was allowed to drink as much beer as she pleased privately but was prohibited from opening a tavern, serving beer, or entering a tavern to drink publicly like a common woman.

HAMMURABI'S CODE THREATENS DEATH BY DROWNING FOR ANY WOMAN TENDING BAR WHO POURS A `SHORT MEASURE' OF BEER FOR A CUSTOMER.

As with the brewing process itself, the first bartenders were women as the Code of Hammurabi makes clear. Among other regulations, Hammurabi's code threatens death by drowning for any woman tending bar who pours a `short measure' of beer for a customer; meaning anyone who does not fill the customer's vessel in accordance with the price paid.

BEER TRAVELS THE WORLD

Through trade, beer travelled to Egypt where the people embraced the brew eagerly. Egyptians loved their beer as much as the Mesopotamians did and breweries grew up all around Egypt. As in Mesopotamia, women were the first brewers and beer was closely associated with the goddess Hathor at Dendera at an early stage. Scholar Richard H. Wilkinson writes:

Hathor was associated with alcoholic beverages which seem to have been used extensively in her festivals, and the image of the goddess is often found on vessels made to contain wine and beer. Hathor was thus known as the mistress of drunkenness, of song, and of myrrh, and it is certainly likely that these qualities increased the goddess's popularity from Old Kingdom times and ensured her persistence throughout the rest of Egypt's history. (143)

Although Hathor encouraged people to freely express their joy in life through drink, it should be noted that drinking to excess was only appropriate under certain conditions. Neither Hathor nor any of the other Egyptian deities smiled upon drunk workers or those who abused alcohol to another's detriment. The universal principle of ma'at (harmony and balance) allowed for excessive drinking but always in balance with the rest of one's daily responsibilities, one's family, and the larger community.

Hathor was not the primary goddess of beer, however; the Egyptian goddess of beer was Tenenit (from one of the Egyptian words for beer, tenemu ) and it was thought the art of brewing was first taught to her by the great god Osiris himself. Like Ninkasi in Sumer, Tenenit brewed her beer from the finest ingredients and oversaw every aspect of its creation.

Beer Brewing in Ancient Egypt

The final result of her efforts was a brew which was enjoyed throughout the land in a number of different varieties. Workers at the Giza plateau received beer rations three times a day and prescriptions for various ailments included the use of beer (over 100 recipes for medicines included the drink). As in Mesopotamia, beer was thought to be healthier than drinking water and was consumed by Egyptians of all ages, the youngest to the oldest.

From Egypt, beer traveled to Greece (as evidenced by the similarity of another of the Egyptian's word for beer, zytum and the ancient Greek for the beverage, zythos ). The Greeks, however, as the Romans after them, favored strong wine over beer and considered the grainy brew an inferior drink of barbarians. The Roman Emperor Julian even composed a poem extolling the virtues of wine as a nectar while noting that beer smelled like a goat. That the Romans did brew beer, however, is evidenced by finds at the Roman outpost in Regensburg, Germany - founded in 179 CE by Marcus Aurelius as Casta Regina- as well as at Trier and other sites.

THE FALL & RISE OF BEER

As the Roman Empire spread, so naturally did Roman culture and tastes. Since the Romans favored wine over beer, beer was considered a distasteful “barbarian beverage” as compared with the cultivated and higher-class drink of wine. Even so, it seems it was primarily the Celts who were first responsible for wine's preferential status over beer as they also considered beer an unfit drink for a man. Nelson writes:

Beer was thought to be an inferior type of intoxicant since it was (at least often) affected by the corrupting power of yeast and was naturally a `cold' and hence effeminate substance while wine was thought to be unaffected by yeast and to be rather a `hot' and hence manly substance. (115-116)

The Gauls were “addicted to the wine imported by Italian merchants which they drank unmixed [with water] and in immoderate amounts to the point of falling into stupors” and also that they were so enamored of wine that they would “exchange a slave for one jar of Italian wine” (Nelson, 48-49). However poorly beer was viewed by the prevailing elite, though, their attitude did nothing to stop people from brewing the drink.

Urartian Beer Pitchers

As Nelson makes clear throughout his work, The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe, the brew recognized in the modern day as `beer' developed in Germany and their brewing techniques then influenced further development throughout Europe. The Germans were brewing beer as early as 800 BCE and their early methods mirrored those of the ancient Sumerians in regard to purity of the brew but with the important addition of hops. Women were also the first brewers in Germany and beer was made from only fresh water, heated, and the best grains. The tradition continued down into the Christian era when monks took up the craft of brewing and sold beer from their monasteries.

Beer was still considered a divine gift, now given by the Christian god, and the evils which might arise from drunkenness was ascribed to the devil (Nelson, 87). The biblical injunction to refrain from drunkenness (Ephesians 5:18) was not thought to apply to the drink itself but rather to overindulgence which opened the door for darker powers to enter one's life rather than one being filled with the Holy Spirit sent from God. This view of beer is similar to that of the people of ancient Mesopotamia who blamed an individual for over-indulgence in drink, and the attendant problems which might arise, but never the drink itself.

By 770 CE, the Christian champion Charlemagne the Great was appointing brewers in France and, like the Babylonians before him, regulated the production, sale, and use of it. Beer was still understood to be healthier to drink than water because of the brewing process and continued to be associated with a divine origin; its popularity also continued undiminished. The Finnish epic, The Kalevala (written in the 17th century CE, but based on much older tales) devotes more lines to beer than to the creation of the world and praises the effects of beer in such a way that they would easily be recognizable to anyone from ancient Sumeria to a modern-day drinker.

Brewers continued to enjoy a special status in their communities until the 19th and 20th centuries CE when temperance groups gained political power in the United States and areas of Europe and were able to effect prohibition to greater or lesser degrees. Even so, the long-established popularity of intoxicants among human beings could not be suppressed by legislation and all the acts of all the governing bodies would not stop brewers and vintners from rising again. In the modern day, beer is as lucrative a commercial venture as it was in the ancient world and the drink retains its popularity on an international scale.Whether an individual is experiencing good or bad times, beer continues to enjoy the same high status it did in ancient Mesopotamia: the drink which makes one's heart feel light.

Apophis › Who Was

Definition and Origins

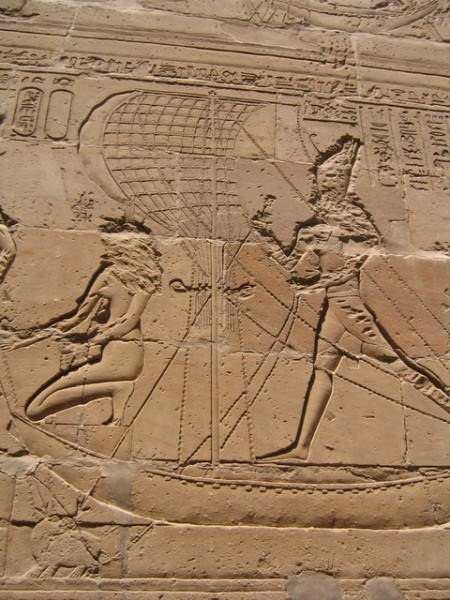

Apophis (also known as Apep) is the Great Serpent, enemy of the sun god Ra, in ancient Egyptian religion. The sun was Ra's great barge which sailed through the sky from dawn to dusk and then descended into the underworld. As it navigated through the darkness of night, it was attacked by Apophis who sought to kill Ra and prevent sunrise. On board the great ship a number of different gods and goddesses are depicted in differing eras as well as the justified dead and all of these helped fend off the serpent.

Ancient Egyptian priests and laypeople would engage in rituals to protect Ra and destroy Apophis and, through these observances, linked the living with the dead and the natural order as established by the gods. Apophis never had a formal cult and was never worshiped, but he would feature in a number of tales dealing with his efforts to destroy the sun god and return order to chaos. Apophis is associated with earthquakes, thunder, darkness, storms, and death, and is sometimes linked to the god Set, also associated with chaos, disorder, storms, and darkness. Set was originally a protector god, however, and appears a number of times as the strongest of the gods on board the sun god's barque, defending the ship against Apophis.

Although there were probably stories about a great enemy-serpent earlier in Egypt 's history, Apophis first appears by name in texts from the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) and is acknowledged as a dangerous force through the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE), especially, and on into the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE) and Roman Egypt. Most of the texts which mention him come from the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE), including the one known as The Book of Overthrowing Apophis which contains the rituals and spells for defeating and destroying the serpent. This work is among the best known of the so-called Execration Texts, works written to accompany rituals denouncing and cursing a person or entity which remained in use throughout ancient Egypt's history.

Ra Travelling Through the Underworld

Apophis is sometimes depicted as a coiled serpent but, often, as dismembered, being cut into pieces, or under attack. A famous depiction along these lines comes from Spell 17 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead in which the great cat Mau kills Apophis with a knife. Mau was the divine cat, a personification of the sun god, who guarded the Tree of Life which held the secrets of eternal life and divine knowledge. Mau was present at the act of creation, embodying the protective aspect of Ra, and was considered among his greatest defenders during the New Kingdom of Egypt.

Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson reprints an image in his book The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt from the tomb of Inerkhau at Deir el-Medina in which Mau is seen defending the Tree of Life from Apophis as he slices into the great serpent's head with his blade. The accompanying text, from Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead, relates how the cat defends Ra and also provides the origin of the cat in Egypt; it was divinely created at the beginning of time by the will of the gods.

MYTHOLOGICAL ORIGINS

According to the most popular creation myth, the god Atum stood on the primordial mound, amidst the swirling waters of chaos, and began the work of creation. The god Heka, personification of magic, was with him, and it was through the agency of magic that order rose from chaos and the first sunrise appeared. A variation on this myth has the goddess Neith emerge from the primal waters and, again with Heka, initiate creation. In both versions, which come from the Coffin Texts, Apophis makes his earliest mythological appearance.

Book of the Dead

In the story concerning Atum, Apophis has always existed and swam in the dark waters of undifferentiated chaos before the ben-ben (the primordial mound) rose from them. Once creation was begun, Apophis was angered because of the introduction of duality and order. Prior to creation, everything was a unified whole, but after, there were opposites such as water and land, light and dark, male and female. Apophis became the enemy of the sun god because the sun was the first sign of the created world and symbolized divine order, light, life, and if he could swallow the sun god, he could return the world to a unity of darkness.

The version in which Neith creates the ordered world is similar but with a significant difference: Apophis is a created being who is given life at the same moment as creation. He is, therefore, not the equal of the earliest gods but their subordinate. In this story, Neith emerges from the chaotic waters of darkness and spits some out as she steps onto the ben-ben. Her saliva becomes the giant serpent who then swims away before it can be caught. When Neith was a part of the waters of darkness, as in the other tale, everything was unified; now, though, there was diversity. Apophis goal was to return the universe to its original, undifferentiated state.

ORDER VS. CHAOS

THE APOPHIS MYTH EPITOMIZES THE MOTIF WHERE THE GODS, THE FORCES OF ORDER, ENLIST THE AID OF HUMANITY TO DEFEND LIGHT AGAINST DARKNESS & LIFE AGAINST DEATH.

One of the most popular literary motifs of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt was order vs. chaos which can be seen in a number of the most famous works. The Admonitions of Ipuwer, for example, contrasts the chaos of the narrator's present with a perfect 'golden age' of the past and the Discourse Between a Man and his Soul does the same on a more personal level. It is not surprising, therefore, to find the Apophis myth emerging during this period because it epitomizes this motif. The gods, the forces of order, enlist the aid of humanity to defend light against darkness and life against death; in essence, to maintain duality and individuality against unity and collectivity.

The personality of an individual was highly valued in Egyptian culture. All the gods were depicted with their own characters and even lesser deities and spirits had their own distinct personalities. The autobiographies inscribed on stelae and tombs was to ensure that the person buried there, that specific individual and their accomplishments, would never be forgotten. Apophis, then, represented everything the Egyptians feared: darkness, oblivion, and the loss of one's identity.

OVERTHROWING APOPHIS

The Egyptians believed that all of nature was imbued with divinity and this, of course, included the sun which gave life.Eclipses and cloudy days were concerning because it was thought the sun god was having problems bringing his ship back up into the sky. The cause of these problems was always Apophis who had somehow gotten the better of the gods on board.During the latter part of the New Kingdom era, the text known as The Book of Overthrowing Apophis was set down from earlier oral traditions in which, according to Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch:

The most terrifying deities in the Egyptian pantheon were evoked to combat the chaos serpent and destroy all the aspects of his being, such as his body, his name, his shadow, and his magic. Priests acted out this unending war by drawing pictures or making models of Apophis. These were cursed and then destroyed by stabbing, trampling, and burning. (108)

Long before the text was written, however, the ritual was enacted. No matter how many times Apophis was defeated and killed, he always rose again to life and attacked the sun god's boat. The most powerful gods and goddesses would defeat the serpent in the course of every night, but during the day, as the sun god sailed slowly across the sky, Apophis regenerated and was ready again by dusk to resume the war. In a text known as the Book of Gates, the goddesses Isis, Neith, and Serket, assisted by other deities, capture Apophis and restrain him in nets held down by monkeys, the sons of Horus, and the great earth god Geb, where he is then chopped into pieces; the next night, though, the serpent is whole again and waiting for the barge of the sun when it enters the underworld.

Mehen

Although the gods were all-powerful, they needed all the help they could get when it came to Apophis. The justified dead who had been admitted to paradise are often seen on the celestial ship helping to defend it. Spell 80 of the Coffin Texts enables the deceased to join in the defense of the sun god and his ship. Set, as noted earlier, is one of the first to drive Apophis off with his spear and club. The serpent god Mehen is also seen on board springing at Apophis to protect Ra. The Egyptian board game mehen, in fact, is thought to have originated from Mehen's role aboard the sun barque. Along with the souls of the dead, however, the living also played a part. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson describes the ritual:

The Egyptians assembled in the temples to make images of the serpent in wax. They spat upon the images, burned them and mutilated them. Cloudy days or storms were signs that Apophis was gaining ground, and solar eclipses were particular times of terror for the Egyptians, as they were interpreted as a sign of Ra's demise. The sun god emerged victorious each time, however, and the people continued their prayers and anthems. (198)

Each morning the sun rose again and moved across the sky and, watching it, the people would know they had played a part in the gods' victory over the forces of darkness and chaos. The first act of the priests in the temples across Egypt was the ritual of Lighting the Fire which re-enacted the first sunrise. This was performed just before dawn in defiance of Apophis' desire to snuff out the light of creation and return all to darkness.

Following Lighting the Fire came the second most important morning ritual, Drawing the Bolt, in which the high priests unlocked and opened the doors to the inner sanctum where the god lived. These two rituals both had to do with Apophis: Lighting the Fire called upon the light of creation to empower Ra and Drawing the Bolt woke the god of the temple from sleep to join in defending the barque of the sun against the great serpent.

CONCLUSION

Rituals surrounding Apophis continued through the Late Period, in which they seem to be taken more seriously than they were previously, and on through the Roman Period. These rituals, in which the people struggled alongside the gods against the forces of darkness, were not particular only to Apophis. The festivals celebrating the resurrection of Osiris included the entire community who participated as two women, playing the parts of Isis and Nephthys, called on Osiris to wake and return to life.At the king's Sed Festival, and others, participants played the parts of the armies of Horus and Set in mock battles re-enacting the victory of Horus (order) over Set (chaos). At Hathor 's festival, people were encouraged to drink to excess in re-enacting the time of disorder and destruction when Ra sent Sekhmet to destroy humanity but then repented. He had a large vat of beer, dyed red, set down in Sekhmet's path at Dendera, and she, thinking it was blood, drank it, became drunk, and passed out.When she woke, she was the gentle Hathor who then restored order and became a friend to humanity.

Set Defeated by Horus

These rituals encouraged the understanding that human beings played an important role in the workings of the universe. The sun was not just an impersonal object in the sky which appeared to rise every morning and set each evening but was imbued with character and purpose: it was the barge of the sun god who, throughout the day, ensured the continuation of life and, at night, required the prayers and support of the people to ensure they would see him the next day. The rituals surrounding the overthrow of Apophis represented the eternal struggle between good and evil, order and chaos, light and darkness, and relied upon the daily attention and efforts of human beings to succeed. Humanity, then, was not just a passive recipient of the gifts of the gods but a vital component in the operation of the universe.

This understanding was maintained, and these rituals observed, until the rise of Christianity in the 4th century CE. At this time, the old model of humanity as co-workers with the gods was replaced by a new one in which human beings were fallen creatures, unworthy of their deity, and utterly dependent upon their god's son and his sacrifice for their salvation. Humans were now considered recipients of a gift they had not earned and did not deserve, and the sun lost its distinct personality and purpose to become another of the Christian god's creations. Apophis, however, would live on in Christian iconography and mythology, merged with other deities such as Set and the benign serpent Sata, as the adversary of God, Satan, who also worked tirelessly to overturn divine order and bring chaos.

LICENSE:

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License