Tophet › Apophis » Ancient origins

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Tophet › Antique Origins

- Apophis › Who Was

Ancient civilizations › Historical and archaeological sites

Tophet › Antique Origins

Definition and Origins

The tophet (also topheth ) was a sacred precinct usually located outside cities where sacrifices and burials were made, especially of young children, in rituals of the Phoenician and then Carthaginian religion. The tophet is the most evident cultural export from Phoenician cities to their colonies throughout the Mediterranean and they have been a valuable source of information on burial practices and even Mediterranean trade via the habit of using imported pottery as funerary urns to store the ashes of the deceased.

FUNCTION OF THE TOPHET

One of the rituals of the Phoenician religion was to sacrifice humans, especially children, according to ancient sources. The victims were killed by fire, although it is not clear precisely how. According to the ancient historians Clitarch and Diodorus, a hearth was set before a bronze statue of the god Baal (or El) who had outstretched arms on which the victim was placed before falling into the fire. They also mention the victims wearing a smiling mask to hide their tears from the god to whom they were being offered. The victim's ashes were then placed in an urn and buried in tombs placed within a dedicated sacred open space surrounded by walls, the tophet.

Tophets are generally located outside the city proper and usually to the north. The tophet at Carthage has a shrine area with an altar where the sacrifices were made. After the ceremony the ashes of the burnt offering were placed within a vessel.Stones were then placed on top of the funerary urns to seal them and placed within the tophet, sometimes within shaft tombs.From the 6th century BCE, stelae were dedicated to Baal or Tanit and placed on top of the urns instead of stones. Many stelae have an inscription which describes a human blood sacrifice or the substitution of a sheep for a child. The urns themselves were often recycled pots and jars from as far afield as Corinth and Egypt and so provide an interesting and valuable record of Phoenician trade.

AT ITS LARGEST EXTENT THE TOPHET OF CARTHAGE COVERED 6,000 SQUARE METERS AND HAS NINE DESCENDING LEVELS.

GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD OF THE TOPHET

Although there is no archaeological evidence from Phoenicia itself of tophets, their presence in so many of its colonies across the Mediterranean attests that this cultural practice almost certainly did come from the home Phoenician cities such as Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos. One of the nearest tophets to Phoenician territory was at Tell Sukas on the Syrian coast, which dates to the 13th-12th century BCE. Regarding colonies, at Motya (off the coast of Sicily ) the tophet there was first used from the mid-7th century BCE. There are also tophets at Sulcis, Bithia, Tharros, and Nora on the island of Sardinia. The most famous tophetis at Carthage, also known as the 'precinct of Tanit' and located to the south of the city at Salammbo. It was first used in the 8th century BCE and continuously thereafter until the fall of Carthage in the Punic Wars. At its largest extent it covered 6,000 square meters and has nine descending levels.

CHILD SACRIFICE

Western Classical writers, describing little-understood eastern practices, gleefully recounted tales of child sacrifice holocausts, which gave the Phoenicians a blood-thirsty reputation throughout antiquity. Roman writers, eager to show that the defeated Carthaginians were barbaric, also exaggerated their Phoenician-inspired cults to better illustrate the virtue of Rome in defeating such a despicable foe. The Bible, too, describes these bloody practices ( molk ) in honour of the god Baal (II Kings 23:10, Exodus 22:29-30 and Jeremiah 7:30-31) locating them near Jerusalem in the valley of Ben Hinnom, literally, a site of slaughter, and stating they were of Phoenician origin. Whether the Phoenicians deserved their reputation as terrible baby-killers has only relatively recently been addressed by modern scholarship.

Firstly, it should be remembered that human sacrifice was carried out in most ancient cultures and is frequently referenced in ancient literature. In the Old Testament Abraham tries to sacrifice his own son Isaac (Genesis 22:1-2), in texts from Ugaritthere is mention of sacrificing the first-born in times of great peril, and in Homer ’s Iliad King Agamemnon is called upon to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia so that the Greek fleet may sail to Troy and reclaim Helen.

Secondly, the scale of human sacrifice carried out by the Phoenicians is difficult to determine but is unlikely to have been performed with any great regularity; no society can, after all, sustain a regular culling of its own population. All of the literary references to human sacrifice suggest that it was necessary only in times of great danger to the state such as wars, plagues, and natural disasters, and was not an everyday practice. Even in Phoenician mythology where the god El sacrifices his son Ieud it is to save his country from collapse. In another example, Diodorus describes the Carthaginian general Hamilcar sacrificing a child during the siege of Agrigento in the 5th century BCE when the defenders were suffering from a fatal outbreak of disease. Further, human sacrifices in ancient sources are almost always the children of rulers and the ruling class, as the gods, apparently, were not to be moved by the sacrifice of the common people.

Thirdly, and most importantly, the very fact that children were sacrificed at all is by no means as certain as ancient sources would have us believe. Whilst the archaeological record has revealed a huge number of funerary urns at tophets, over 20,000 at Carthage alone, and the majority contain the burnt remains of children, this does not necessarily indicate the children were sacrificed.

Tophet's steles

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Analysis of remains within the tophet at Carthage reveals that internment of urns was regular and individual, ie not en masse.From the 7th to 6th centuries BCE the deceased were newborn babies while those dating from the 4th century BCE were mostly up to 3 years old. There are also, right from the beginning of the tophet, burnt remains of animals, and these account for 30% of the remains from the early period. From the 4th century BCE animal remains account for only 10% of the total. In both periods there are examples of urns with a mix of human and animal remains. Analysis also reveals that, overall, 80% of the human remains are from newborn babies or foetuses. This compares to findings at Tharros where 98% of the remains were from babies younger than three months old. The exact cause of death is not possible to determine but historian ME Aubet concludes the following,

...everything points to them dying of natural causes, at birth or a few weeks later. Although human sacrifice may have been practised, the high proportion of newborn babies in the tophets shows that these enclosures served as burial places for children who died at birth or had not reached the age of two. (252)

Further, 'The absence of tombs containing the newborn in the Phoenicio- Punic necropolises of the central Mediterranean would confirm that children were not buried next to adults, but in the tophet. ' (253).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it seems that the reputation of the Phoenicians, and then the Carthaginians after them, as blood-thirsty child murderers lacks substantial physical evidence to support it. That child sacrifice did occur, as it did in other ancient religions, seems without doubt. However, the position that this was done only in times of great social stress and that the tophet is actually a sacred place for other types of sacrifice and a burial place for children who died a natural death has much to support it.

Apophis › Who Was

Definition and Origins

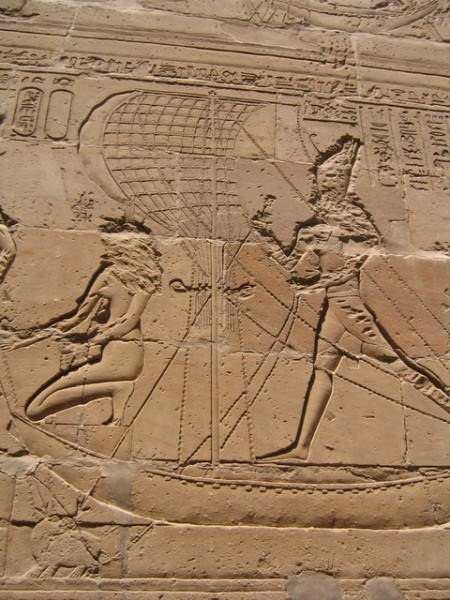

Apophis (also known as Apep) is the Great Serpent, enemy of the sun god Ra, in ancient Egyptian religion. The sun was Ra's great barge which sailed through the sky from dawn to dusk and then descended into the underworld. As it navigated through the darkness of night, it was attacked by Apophis who sought to kill Ra and prevent sunrise. On board the great ship a number of different gods and goddesses are depicted in differing eras as well as the justified dead and all of these helped fend off the serpent.

Ancient Egyptian priests and laypeople would engage in rituals to protect Ra and destroy Apophis and, through these observances, linked the living with the dead and the natural order as established by the gods. Apophis never had a formal cult and was never worshiped, but he would feature in a number of tales dealing with his efforts to destroy the sun god and return order to chaos. Apophis is associated with earthquakes, thunder, darkness, storms, and death, and is sometimes linked to the god Set, also associated with chaos, disorder, storms, and darkness. Set was originally a protector god, however, and appears a number of times as the strongest of the gods on board the sun god's barque, defending the ship against Apophis.

Although there were probably stories about a great enemy-serpent earlier in Egypt 's history, Apophis first appears by name in texts from the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) and is acknowledged as a dangerous force through the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE), especially, and on into the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE) and Roman Egypt. Most of the texts which mention him come from the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE), including the one known as The Book of Overthrowing Apophis which contains the rituals and spells for defeating and destroying the serpent. This work is among the best known of the so-called Execration Texts, works written to accompany rituals denouncing and cursing a person or entity which remained in use throughout ancient Egypt's history.

Ra Travelling Through the Underworld

Apophis is sometimes depicted as a coiled serpent but, often, as dismembered, being cut into pieces, or under attack. A famous depiction along these lines comes from Spell 17 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead in which the great cat Mau kills Apophis with a knife. Mau was the divine cat, a personification of the sun god, who guarded the Tree of Life which held the secrets of eternal life and divine knowledge. Mau was present at the act of creation, embodying the protective aspect of Ra, and was considered among his greatest defenders during the New Kingdom of Egypt.

Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson reprints an image in his book The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt from the tomb of Inerkhau at Deir el-Medina in which Mau is seen defending the Tree of Life from Apophis as he slices into the great serpent's head with his blade. The accompanying text, from Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead, relates how the cat defends Ra and also provides the origin of the cat in Egypt; it was divinely created at the beginning of time by the will of the gods.

MYTHOLOGICAL ORIGINS

According to the most popular creation myth, the god Atum stood on the primordial mound, amidst the swirling waters of chaos, and began the work of creation. The god Heka, personification of magic, was with him, and it was through the agency of magic that order rose from chaos and the first sunrise appeared. A variation on this myth has the goddess Neith emerge from the primal waters and, again with Heka, initiate creation. In both versions, which come from the Coffin Texts, Apophis makes his earliest mythological appearance.

Book of the Dead

In the story concerning Atum, Apophis has always existed and swam in the dark waters of undifferentiated chaos before the ben-ben (the primordial mound) rose from them. Once creation was begun, Apophis was angered because of the introduction of duality and order. Prior to creation, everything was a unified whole, but after, there were opposites such as water and land, light and dark, male and female. Apophis became the enemy of the sun god because the sun was the first sign of the created world and symbolized divine order, light, life, and if he could swallow the sun god, he could return the world to a unity of darkness.

The version in which Neith creates the ordered world is similar but with a significant difference: Apophis is a created being who is given life at the same moment as creation. He is, therefore, not the equal of the earliest gods but their subordinate. In this story, Neith emerges from the chaotic waters of darkness and spits some out as she steps onto the ben-ben. Her saliva becomes the giant serpent who then swims away before it can be caught. When Neith was a part of the waters of darkness, as in the other tale, everything was unified; now, though, there was diversity. Apophis goal was to return the universe to its original, undifferentiated state.

ORDER VS. CHAOS

THE APOPHIS MYTH EPITOMIZES THE MOTIF WHERE THE GODS, THE FORCES OF ORDER, ENLIST THE AID OF HUMANITY TO DEFEND LIGHT AGAINST DARKNESS & LIFE AGAINST DEATH.

One of the most popular literary motifs of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt was order vs. chaos which can be seen in a number of the most famous works. The Admonitions of Ipuwer, for example, contrasts the chaos of the narrator's present with a perfect 'golden age' of the past and the Discourse Between a Man and his Soul does the same on a more personal level. It is not surprising, therefore, to find the Apophis myth emerging during this period because it epitomizes this motif. The gods, the forces of order, enlist the aid of humanity to defend light against darkness and life against death; in essence, to maintain duality and individuality against unity and collectivity.

The personality of an individual was highly valued in Egyptian culture. All the gods were depicted with their own characters and even lesser deities and spirits had their own distinct personalities. The autobiographies inscribed on stelae and tombs was to ensure that the person buried there, that specific individual and their accomplishments, would never be forgotten. Apophis, then, represented everything the Egyptians feared: darkness, oblivion, and the loss of one's identity.

OVERTHROWING APOPHIS

The Egyptians believed that all of nature was imbued with divinity and this, of course, included the sun which gave life.Eclipses and cloudy days were concerning because it was thought the sun god was having problems bringing his ship back up into the sky. The cause of these problems was always Apophis who had somehow gotten the better of the gods on board.During the latter part of the New Kingdom era, the text known as The Book of Overthrowing Apophis was set down from earlier oral traditions in which, according to Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch:

The most terrifying deities in the Egyptian pantheon were evoked to combat the chaos serpent and destroy all the aspects of his being, such as his body, his name, his shadow, and his magic. Priests acted out this unending war by drawing pictures or making models of Apophis. These were cursed and then destroyed by stabbing, trampling, and burning. (108)

Long before the text was written, however, the ritual was enacted. No matter how many times Apophis was defeated and killed, he always rose again to life and attacked the sun god's boat. The most powerful gods and goddesses would defeat the serpent in the course of every night, but during the day, as the sun god sailed slowly across the sky, Apophis regenerated and was ready again by dusk to resume the war. In a text known as the Book of Gates, the goddesses Isis, Neith, and Serket, assisted by other deities, capture Apophis and restrain him in nets held down by monkeys, the sons of Horus, and the great earth god Geb, where he is then chopped into pieces; the next night, though, the serpent is whole again and waiting for the barge of the sun when it enters the underworld.

Mehen

Although the gods were all-powerful, they needed all the help they could get when it came to Apophis. The justified dead who had been admitted to paradise are often seen on the celestial ship helping to defend it. Spell 80 of the Coffin Texts enables the deceased to join in the defense of the sun god and his ship. Set, as noted earlier, is one of the first to drive Apophis off with his spear and club. The serpent god Mehen is also seen on board springing at Apophis to protect Ra. The Egyptian board game mehen, in fact, is thought to have originated from Mehen's role aboard the sun barque. Along with the souls of the dead, however, the living also played a part. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson describes the ritual:

The Egyptians assembled in the temples to make images of the serpent in wax. They spat upon the images, burned them and mutilated them. Cloudy days or storms were signs that Apophis was gaining ground, and solar eclipses were particular times of terror for the Egyptians, as they were interpreted as a sign of Ra's demise. The sun god emerged victorious each time, however, and the people continued their prayers and anthems. (198)

Each morning the sun rose again and moved across the sky and, watching it, the people would know they had played a part in the gods' victory over the forces of darkness and chaos. The first act of the priests in the temples across Egypt was the ritual of Lighting the Fire which re-enacted the first sunrise. This was performed just before dawn in defiance of Apophis' desire to snuff out the light of creation and return all to darkness.

Following Lighting the Fire came the second most important morning ritual, Drawing the Bolt, in which the high priests unlocked and opened the doors to the inner sanctum where the god lived. These two rituals both had to do with Apophis: Lighting the Fire called upon the light of creation to empower Ra and Drawing the Bolt woke the god of the temple from sleep to join in defending the barque of the sun against the great serpent.

CONCLUSION

Rituals surrounding Apophis continued through the Late Period, in which they seem to be taken more seriously than they were previously, and on through the Roman Period. These rituals, in which the people struggled alongside the gods against the forces of darkness, were not particular only to Apophis. The festivals celebrating the resurrection of Osiris included the entire community who participated as two women, playing the parts of Isis and Nephthys, called on Osiris to wake and return to life.At the king's Sed Festival, and others, participants played the parts of the armies of Horus and Set in mock battles re-enacting the victory of Horus (order) over Set (chaos). At Hathor 's festival, people were encouraged to drink to excess in re-enacting the time of disorder and destruction when Ra sent Sekhmet to destroy humanity but then repented. He had a large vat of beer, dyed red, set down in Sekhmet's path at Dendera, and she, thinking it was blood, drank it, became drunk, and passed out.When she woke, she was the gentle Hathor who then restored order and became a friend to humanity.

Set Defeated by Horus

These rituals encouraged the understanding that human beings played an important role in the workings of the universe. The sun was not just an impersonal object in the sky which appeared to rise every morning and set each evening but was imbued with character and purpose: it was the barge of the sun god who, throughout the day, ensured the continuation of life and, at night, required the prayers and support of the people to ensure they would see him the next day. The rituals surrounding the overthrow of Apophis represented the eternal struggle between good and evil, order and chaos, light and darkness, and relied upon the daily attention and efforts of human beings to succeed. Humanity, then, was not just a passive recipient of the gifts of the gods but a vital component in the operation of the universe.

This understanding was maintained, and these rituals observed, until the rise of Christianity in the 4th century CE. At this time, the old model of humanity as co-workers with the gods was replaced by a new one in which human beings were fallen creatures, unworthy of their deity, and utterly dependent upon their god's son and his sacrifice for their salvation. Humans were now considered recipients of a gift they had not earned and did not deserve, and the sun lost its distinct personality and purpose to become another of the Christian god's creations. Apophis, however, would live on in Christian iconography and mythology, merged with other deities such as Set and the benign serpent Sata, as the adversary of God, Satan, who also worked tirelessly to overturn divine order and bring chaos.

LICENSE:

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License