Cavalry in Ancient Chinese Warfare › Agora › Agrigento » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Cavalry in Ancient Chinese Warfare › Origins

- Agora › Origins

- Agrigento › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Cavalry in Ancient Chinese Warfare › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

The use of cavalry in Chinese warfare was a significant development which was largely responsible for the abandonment of chariots, that vehicle being much slower and more cumbersome to manoeuvre in battle conditions. The greater speed and mobility of cavalry not only changed battlefield dynamics and troop deployments but also necessitated a far greater investment in fixed defences than previously. An enemy which could attack at any time, on any terrain, and without warning became a disconcerting feature of Chinese warfare from the 4th century BCE onwards.

Chinese Cavalry Rider

ORIGINS & DEVELOPMENTS

Although horses had been domesticated since Neolithic times in China, the animal was not ridden for centuries, perhaps only from the end of the Spring and Autumn period in the 5th century BCE did horse riding become common. A few historians continue to maintain that horses were ridden on hunting trips during the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 - 1046 BCE), but these views are in the minority and there is little supporting archaeological evidence. The first encounters with horse riders by the Chinese would likely have been when they met nomadic peoples in the western border regions. The first were probably the Hu people in the late 4th century BCE who attacked the Chao and Yen states. An immediate effect of cavalry use was a realisation that static defences would have to be spread over a very wide area and maintained at high costs in order to combat a now much more mobile enemy. The Chinese were then quick to imitate the new approach to warfare, even copying the trousers and short jackets such foreign horse riders wore in an effort to wholly capture the magical effect of cavalry on what had been up to that point a somewhat static battlefield. There were practical developments in clothing too, with cumbersome robes and long coats replaced by jackets, boots, and trousers held up by buckles.Still, despite its obvious advantages, cavalry units remained only a small corps within a much larger Chinese army until the Han period (206 BCE - 220 CE). The Qin state army of the 3rd century BCE was composed of only around 10% cavalry.Gradually, the prestige of the chariot and its obvious dramatic visual effect gave way to an understanding that the limiting necessity for level ground and their poor mobility when in action (four-horse chariots require a good deal of ground to make an about turn) meant that single horse riders were a far superior shock weapon. The armies of the early Han doubled the cavalry component to 20% of the total army and used it to good effect in Han founder, Liu Pang's battles with Hsiang Yu.CAVALRY UNITS REMAINED ONLY A SMALL CORPS WITHIN A MUCH LARGER CHINESE ARMY UNTIL THE HANPERIOD (206 BCE - 220 CE).

SELECTING HORSES & MEN

Horses, indigenous to ancient China, were quite small compared to those available to the northern nomadic tribes of Asia, and now that cavalry troops had proven their worth, Chinese commanders began to look for better mounts. Emperor Wu (r. 141-87 BCE) embarked on several campaigns specifically to capture horses from the peoples of central Asia which were famous for being stronger, swifter and having greater endurance. The expedition was itself said to have included a 10,000-strong cavalry force. Once acquired, horses were looked after well on state-controlled grasslands and stables where they were kept in cool sheds in summer and warm ones in winter. Their manes were kept trimmed, their hooves cared for, and in battle, they wore blinkers and ear protectors to minimise the effects on their nerves of the noise and action of the battlefield. To protect them to some degree from enemy spears, horses sometimes wore an armour-plated covering hanging from their necks made of bronze, iron and leather or cloth.

Han Mounted Archer

As to the men that would ride the horses, long training and great skill were required to manage a horse in battle conditions, especially given the primitive nature of saddles - usually only a rolled blanket - and the late arrival of stirrups (from the Han period). Even more skill was required to effectively use a weapon from this precarious seat - a lance, bow, halberd (a mix of axe and spear), or sword. For this reason, many dynasties simply recruited experienced riders from neighbouring states; a policy which continued into the Three Kingdoms period (220-280 CE). The 3rd century BCE military treatise the Six Secret Teachings by T'ai Kung has this to say on the skills required by cavalrymen:The rule for selecting cavalry warriors is to take those under forty, who are at least seven feet five inches tall, strong and quick, who surpass the average. Men who, while racing a horse, can fully draw a bow and shoot. Men who can gallop forward and back, left and right, and all around, both advancing and withdrawing. Men who can jump over moats and ditches, ascend hills and mounds, gallop through narrow confines, cross large marshes, and race into a strong enemy, causing chaos among their masses. (Sawyer, 2007, 101)

USE & TACTICS

Cavalry units were used as a shock weapon, just as their predecessor the chariot had been. Horsemen could attack the enemy to break up their infantry lines and disrupt the opposing commander's planned tactical formations. Armed with bows and able to fire them on the move, riders could engage in hit-and-run attacks. Being highly mobile, cavalry also allowed unorthodox tactics to be used on a battlefield which had once been somewhat formulaic in its troop deployments, especially during the ascendancy of chariots. T'ai Kung describes his idea of the ideal deployment of cavalry:Cavalry are the army's fleet observers, the means to pursue a defeated army, to sever supply lines, to strike roving forces…Ten cavalrymen can drive off one hundred infantrymen, and one hundred cavalrymen can run off one thousand men…As for the number of officers in the cavalry: a leader for five men; a captain for ten; a commander for one hundred; a general for two hundred.While it is not certain if commanders in the field ever actually followed this advice, such military treatises were widely studied and even memorised by some commanders. It is also true that most were composed based on tried and tested methods. For how long such advice remained valid is another moot point. One common deployment of cavalry was to set them at the wings of infantry formations, protecting them from outflanking manoeuvres by the enemy. Cavalry was also used to protect an armies rear when it was on the move. By the 2nd century BCE, cavalrymen carried shields but these were likely for fighting when they dismounted as most cavalry weapons required two hands to use. There are also episodes where commanders innovated such as one officer in Sima Yi's army who, in a battle in 303 CE, had a few thousand of his cavalrymen tie a double-ended halberd to either side of their horse before charging the enemy and gaining victory.

The rule for fighting on easy terrain: Five cavalrymen will form one line, and front to back their lines should be separated by twenty paces, left to right four paces, with fifty paces between attachments.

On difficult terrain the rule is front to back, ten paces; left to right, two paces; between detachments, twenty-five paces. Thirty cavalrymen comprise a company; sixty form a regiment. For ten cavalrymen there is a captain.(Sawyer, 2007, 99-100)

Northern Wei Cavalry Rider

The adoption of the stirrup and better saddles meant that riders had much greater control of their mount and could carry heavier arms and armour. The 4th century CE saw the introduction of heavy cavalry with cataphract armour protecting the whole body of both the rider and the horse. The innovation was probably introduced into China from Manchuria, and their earliest depiction in art comes from a 357 CE Korean tomb (in an area then controlled by Chinese commanderies). Such heavy cavalry, used to bash a way through and disrupt enemy formations, softening them up before the infantry arrived, became the elite corps of the Chinese army and akin to the knights of medieval Europe.DEFENCES AGAINST CAVALRY

A defence tactic against cavalry units was to set wooden caltrops (spiked devices) in the ground the enemy was expected to approach. They are mentioned in the Six Secret Teachings :Wooden caltrops which stick out of the ground about two feet five inches [70 cm]…They are employed to defeat infantry and cavalry, to urgently press the attack against invaders, and to intercept their flight…For narrow roads and small bypaths, set out iron caltrops eight inches [20 cm] wide, having hooks four inches high and shafts of more than six feet [1.8 m]…They are for defeating retreating cavalry. (Sawyer, 2007, 77-8)Other defences against a band of marauding cavalry included the use of iron chains strung across paths, covered ditches, and setting spears into grassy ground at an angle with the point upwards, colourfully called “Dragon Grass”.

LATER CAVALRY & DECLINE

Cavalry continued to be used effectively into the Sui dynasty (581-618 CE) with, as before, riders often recruited from outside China. The Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), too, recruited from abroad and used East Turk and Uighur horsemen, mixing them with their own troops to form cavalry corps in their tens of thousands. That period also saw a return to a lighter and more mobile cavalry. However by the 9th century CE, and despite the continuance of elite cataphract units, cavalry had largely fallen out of favour as a major component of field armies, a decision the Chinese would later rue. For history would eventually turn full circle and the Chinese armies, although they had once made themselves proficient users of cavalry, would again be taught a lesson in horsemanship and warfare by the steppe nomads just as they had been in the 5th century BCE. This time they were undone by the cavalry forces of the Mongol empire whose skill, speed, love of feigned retreats, and total lack of interest in positional warfare brought the “barbarians” victory after victory and eventual control of the Chinese state in the 13th century CE.Agora › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

TRADERS IN THE AGORA

Retail traders (known as kapeloi ) served as middle-men between the craftsmen and the consumer but were largely mistrusted in ancient times as unnecessary parasites (in his Politics Aristotle states that the kapeloi served a “kind of exchange which is justly censured; for it is unnatural and a mode by which men unfairly gain from one another”). These retail traders were mostly metics (not free-born citizens of the city, today known as 'legal aliens') while the craftsmen could be metics, citizens or even freed slaves who had become skilled artisans.In the Agora of Athens there were confectioners who made pastries and sweets, slave-traders, fishmongers, vintners, cloth merchants, shoe-makers, dress makers, and jewelry purveyors. A special separate 'potters market' was reserved for the buying and selling of cookware as that was considered solely the provenance of women and was frequented by female slaves on task for their mistresses or by the poorer wives and daughters of Athens.THE ATHENIAN AGORA HOSTED ALL MANNER OF MERCHANTS, FROM CONFECTIONERS TO SLAVE TRADERS.

PHILOSOPHERS & THE AGORA

It was in the Agora of Athens that the great philosopher Socrates questioned the market-goers on their understanding of the meaning of life, attracting a crowd of Athenian youth who enjoyed seeing the more pretentious of their elders made fools of. In this marketplace, one day, the young poet Aristocles son of Ariston heard Socrates speaking, went and burned all his works, and became the philosopher known as Plato. His philosophical dialogues, coupled with his founding of the Academy, the first University, and his role as the teacher of Aristotle who then was tutor to Alexander the Great, changed western philosophy.A contemporary of Plato's, Diogenes of Sinope, lived in a tub in the Agora and followed Socrates' example of questioning the Athenians on their understanding of the more important aspects of life. Diogenes is well known for searching for an honest man (though, actually, he claimed he was searching for a real human being) by holding a candle or lantern to people's faces in the agora.

Agora Gate, Ephesos

THE ROMAN AGORA

In Rome the agora would serve in much the same way as it did in Greek city-states such as Athens but was known as The Forum (literally `the place outdoors'). As in Greece, the women frequented the out-door market to shop while the men would meet there to discuss politics or events of the day. Among the most popular commodities of the Roman market was silk, both in the time of the Roman Republic and during the Roman Empire. So popular was silk that laws needed to be enacted to encourage modesty among the women of Rome who wore the sheer fabric daily to public events. In time, these laws were also applied to men who came to appreciate silk as much as the women. Latin writers frequently make fun of those their fellow citizens and their behavior at market. The Roman satirist Juvenal and the poet Horace, as well as other writers, found much of their inspiration in watching and listening to those who gathered for shopping in the open-air market.Agrigento › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

In mythology, Agrigento was founded by Daedalus and his son Icarus following their flight from Crete, but in the historical record, the city-state or polis was founded in c. 580 BCE by settlers from Rhodes and Crete who had a century earlier founded the nearby city of Gela. The most notable early ruler was the tyrant Phalaris (c. 570-549 BCE) who expanded the city's influence in the surrounding territory and built the impressive fortification walls. The tyrant became famous in legend because of his innovative approach to executions. The condemned were put inside a huge bronze bull which was then heated over a fire. Phalaris was tickled by the screams coming from inside the bull which made it seem like the animal was bellowing with rage. A similar period of local dominance was enjoyed during the reign of another tyrant Theron (c. 489-473 BCE) who was noted as a just ruler and patron of the arts. Siding with Syracuse against Carthage, the city prospered following the battle of Himera in 480 BCE, although there was a significant battle with Hieron, the tyrant of Syracuse, in c. 472 BCE. From this period the city became known for its architectural splendour, especially its large Doric temples built using sandstone. So much so, that Pindar, in writing an ode to an Olympic victor, wrote: 'Akragas, the most beautiful city the mortals had ever built'. Diodorus described the city as one of the richest in the Greek world and the noted philosopher and medical expert Empedocles (c. 492-432 BCE), who came from Agrigento, famously said of the city's inhabitants and their easy living: '...they party as if they will die tomorrow, and build as if they will live for ever'.Agrigento was neutral in the war between Athens and Syracuse in 413 BCE but was attacked, besieged for seven months, and then destroyed by the Carthaginians in 406 BCE - emphatic revenge for their defeat at Himera in 480 BCE. The town did eventually recover and became an important Hellenistic settlement, but Agrigento was again sacked in 262 BCE and 210 BCE, this time by the Romans. However, the new masters did ensure a new period of prosperity for Agrigento. The Hellenistic- Roman area of the city survives in part today and was laid out in a regular grid pattern with six principal roads dividing the town into bands. Villas with surviving frescoes and mosaics attest to the wealth enjoyed by some of the city's residents. The town continued to prosper into the Byzantine period and the distinctive semi-circular tombs carved into the sandstone rocks can still be seen by the modern visitor.AGRIGENTANS 'PARTY AS IF THEY WILL DIE TOMORROW, AND BUILD AS IF THEY WILL LIVE FOREVER' EMPEDOCLES

Temple of Juno, Agrigento

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS

The Temple of Concord Constructed between 450 and 430 BCE, it is one of the best-preserved Greek temples anywhere and is often described as the Parthenon of Magna Graecia. Measuring 40 x 17 metres, the Doric temple was probably dedicated to Castor and Pollux.The interior consists of a pronaos, cella, and opistodomos, where treasure, offerings, and public records were kept. There are six columns on each façade and 13 along the longer sides; each consists of four fluted drums. The frieze has alternating triglyphs and plain metopes. The temple is in such good condition largely because it was converted into a Christian basilica in 597 CE, when the interior was converted into arcades with three naves. The Temple of the Dioscuri (Castor & Pollux) The name is a convention and the remains today were reconstructed in the 19th century CE. Originally, the 5th century BCE temple measured around 34 x 16 metres and had a 6 x 13 arrangement of external columns. It was destroyed in the siege of 406 BCE. In front of the temple is a circular altar, once used to sacrifice animals and pour libations in religious ceremonies and an important part of the sanctuary to Demeter and Persephone. The Temple of Hercules The oldest temple at the site was built in c. 510 BCE in honour of the Greek hero Hercules who was particularly revered at Agrigento. The temple base measures 73.9 x 27.7 metres and the full height would have been around 16 metres. Originally, there were 6 columns on each façade and 15 along the sides, but today only nine are still standing, re-erected in 1922 CE.Each column was composed of four fluted drums and the pediment would have carried decorative sculpture. A bronze statue once stood in the interior. The Temple of Juno (Hera Lacinia) Constructed between 450 and 430 BCE, the Doric temple measured around 41 x 20 metres and 15.3 m in height. Originally, there were six columns on each façade and 13 along the long sides. Each column consists of four drums and 30 are still standing today. Interestingly, one can still see here and there the black stains of fire damage caused by the Carthaginian attack in 406 BCE. Within the temple stood a statue of the goddess, Hera (Roman name: Juno), revered for her role as protectress of marriages and wedding ceremonies, and rites would have once taken place outside the temple; the ruins of the massive altar can still be seen today.

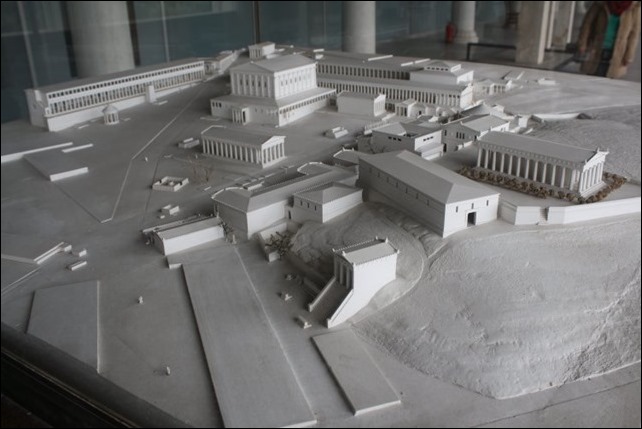

Temple of Zeus Model, Agrigento

The Temple of Zeus The massive temple of Zeus (or Olympieion) was built in the 480s BCE to commemorate the victory over Carthage at the battle of Himera. One of the largest temples built in antiquity, measuring around 113 x 56 metres and standing on a five-step base, it was 33 metres high and the size of a modern football stadium. It was also unusual in that instead of the typical external free-standing columns, the unusually thick columns (7 on the façades x 14 on the long sides) were engaged in a half- wall, and the upper inter-spaces between the columns were filled with huge atlantide figures (the male version of the caryatid, also known as telemones) seemingly holding up the roof with their bent arms. These 38 god-like figures were 7.6 metres tall but their exact positioning is still debated by scholars. The height of the temple columns alone was 16.88 metres and their width at the base 4.22 metres. According to Diodorus, the pediments had sculptures representing a gigantomachy and scenes from the Trojan War. The temple is also an early and rare example in Greek architecture of the use of iron within the stone blocks. Slots were cut into the stones of the architrave into which were placed iron bars (31 x 10 cm) which provided structural support while the stones were assembled into position. They had no beneficial effect once the blocks were in place but provided tensile strength whilst construction was on-going for the large architrave blocks which spanned the unusually large gap between columns. The temple was actually not quite finished when it was destroyed by the Carthaginians in 406 BCE.

Kouros (The Agrigento Youth)

Theron's Tomb Tradition ascribed this monument to Theron, considering it his tomb, but, in fact, the structure is a 1st century BCE Roman monument probably commemorating the siege of 262 BCE. A combination of Doric and Ionic architectural elements, the monument is 9.3 m high and 5.2 m wide. A slender pyramid, now lost, once stood atop the structure.OTHER STRUCTURES & ARTEFACTS

Other structures of note are the temple of Hephaistos, built in c. 430 BCE, of which only two columns and a part of the base survive. There is also the temple of Asclepius, the centre-piece of a 10,000 square metre sanctuary to the god of healing constructed between 400 and 390 BCE. Finally, there is also a well-preserved 4th century BCE Ekklesiasterion, once used for public assemblies. Unsurprisingly for such an important settlement, the site is also a rich source of artefacts dating back to the Neolithic period.Star pieces include some of the huge atlantides from the temple of Zeus, a fine marble kouros, an expressive marble warrior torso, finely carved Roman sarcophagi, and an excellent selection of Greek red and black-figure pottery. These are all housed in the archaeological museum of Agrigento.License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License