Arminius › Arretium › Women's Work in Ancient Egypt » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Arminius › Who was

- Arretium › Origins

- Women's Work in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Arminius › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

The Cherusci noble Arminius (c. 18 BCE - 19 CE) led the resistance to Roman conquest of Germania during the years 9-16 CE. Likely raised as a child hostage in Rome , Arminius gained command of a German auxiliary cohort in the Roman army .Posted on the Rhine, Arminius served under the command of Governor Publius Q. Varus. Varus' task was to complete the conquest of Germania but his rough-handed methods and demands for tax incited the tribes into revolt. Seeing his countrymen oppressed by the Romans, Arminius became the leader of the rebels. In 9 CE Arminius lured Varus into an ambush in the Teutoburg Forest. Varus fell on his sword as his legions were decimated around him. It was one of Rome's worst defeats and caused Emperor Augustus to abandon the conquest of Germania.

Nevertheless, the Roman hero Germanicus continued to lead campaigns of retribution. Arminius suffered defeats but won the war , when Germanicus was recalled to Rome by the new emperor Tiberius . Having successfully liberated and defended Germania against the Romans, Arminius next squared off against Maroboduus, the powerful king of the Marcomanni.Defeating Maroboduus, Arminius had become the most powerful leader in Germania. Arminius aspired to be king but many tribal factions resented his authority. Betrayed by his relatives, Arminius was killed in 19 CE.

ARMINIUS IN THE SERVICE OF ROME

Born c. 18 BCE, Arminius was the eldest son of the Cherusci chief Segimer. To secure peace with Rome, Segimer is thought to have surrendered both Arminius and his younger brother Flavus to Rome as child hostages. Raised like noble Romans, the brothers learned Latin and the Roman way of war. Most likely both brothers fought beside the legions under Tiberius ClaudiusNero , stepson of Emperor Augustus, suppressing the huge Pannonian and Illyrian revolts of 7-9 CE.

Around 8 CE Arminius was transferred to the Rhine to serve under Governor Publius Quinctilius Varus . Varus' mission was to turn Germania Magna (Greater Germany), the tribal territories east of the Rhine, into a full-fledged Roman province. The tribes had largely been pacified in the Tiberius' campaigns of 4-5 CE. Tiberius had achieved more by negotiations and diplomacy than had been gained by two decades of warfare . Varus, however, demanded tribute and treated the natives like slaves. Soon the tribes simmered with revolt.

Coin inscribed VAR(us)

Varus trusted and liked his charismatic auxiliary commander, Arminius, who was also a useful liaison with the tribal nobility.During the summer 9 CE, Varus marched his army of three legions and supporting auxiliaries from Vetera (Xanten) on the Rhine into central Germania. Varus' army took the route along the Lippe River and from there north to the western regions of the Weser Hills. He built a camp on the upper Weser River, right in the middle of Cherusci territory. Varus collected tribute and meted out Roman justice and law, and tribesmen came to trade at the huge Roman camp. For Arminius, however, it meant a chance to reunite with his family, and soon Arminius and Segimer sat together at Varus' table, assuring him all was well.

ARMINIUS TURNS AGAINST ROME

Arminius and Segimer's goodwill was but a farce, meant to fool Varus until it was time to throw off the Roman yoke. Although the Cherusci had received federated status within the empire , to Arminius it was clear that his people were not treated as equals. As he saw it, Rome took Germania's youths to fight in Rome's armies and the people were fleeced of what little wealth they possessed. The Romans even destroyed the land itself, cutting down the timber of ancient and sacred forests. Arminius met the chieftains in a secret glade to plot the Romans' demise.

TO DEFEAT THE LEGIONS, ARMINIUS UNITED THE TRIBES & LURED VARUS' LEGIONS INTO THE TEUTOBURG FOREST WHERE THE DIFFICULT TERRAIN FAVORED THE LIGHTER-ARMED GERMANIC WARRIORS.

Arminius knew that the legions would not go down easily. The huge Roman camp dwarfed the local villages, and its fortifications made the legionaries near invincible. The legionaries had better armor, weapons, and discipline than the Germanic warriors, the vast bulk of which were farmers. The nobles did have bands of well-armed personal retainers, but these were relatively few in number. To defeat the legions, Arminius united the tribes. He would lure Varus and his legions into the Teutoburg Forest. There the difficult terrain favored Arminius' lighter-armed, quick and nimble Germanic warriors.

Not all the Germanic chiefs were ready to give up the privileges they received from Rome. Arminius' uncle Inguiomerus opted to stay neutral while the herculean Segestes even revealed the conspiracy to Varus. Varus, however, thought Segestes' warning as nothing more than slander. Varus was well aware that Segestes did not like Arminius because Arminius had his eye on Thusnelda, Segestes' daughter, who was already betrothed to somebody else.

With the approach of fall, the Roman army prepared to march back to their winter quarters on the Rhine. At this time news arrived of a tribal revolt to the northwest. Arminius suggested that instead of taking the usual route to the Rhine via the Lippe Varus should take a different route north of the Weser Hills. That way he could crush the insurrection on the way. Varus took the bait and marched his three legions, auxiliaries, and supporting staff into the Teutoburg Forest.

THE BATTLE OF THE TEUTOBURG FOREST

Arminius rode away from the plodding Roman column after he told Varus that he was off to gather more reinforcements.Reinforcements came, not just from the Cherusci but also from the Marsi, the Bructeri, and from other tribes as well. They did not come to aid the Romans, though, but to destroy them. Segestes, however, remained loyal to Rome. He even tried holding Arminius captive for a while but was forced to release him. Having little choice, Segestes threw his lot in with the rebels.

The weather also turned against the Romans who were caught in a thunderstorm on the second day. Mud and puddles, overflowing creeks, and fallen branches slowed down wheel, hoof, and foot. Then the skirmishing attacks began. The barbarians showered the Romans with javelins and sling stones; striking at soldiers, civilians, and pack animals alike.Seasoned centurions tried to restore order and counter-attack but the terrain jumbled up Roman formations and their heavy armor made the legionaries too slow. Arminius was likely in the thick of it, personally leading the most critical attacks, as well as taking time co-ordinate the deployment of the various tribal forces along the Roman route.

The weary Romans were able to entrench themselves for a night of much-needed rest. Varus was aware that Arminius had betrayed him and that he was faced with a major uprising. However, the way ahead seemed far shorter than backtracking to the Lippe. The next day Varus pressed on, abandoning most of his heavy and surplus equipment to lighten the load. At times the weather improved, at times the woods gave way to fields of long grasses, but the attacks continued.

Battle of Teutoburg Forest

At least the legions were able to find suitable ground for their marching camp. By the end of the third day, Varus' army had reached the edge of Kalkrieser Berg (mountain), part of the northern extremities of the Weser Hills, which protruded into the Great Moor. Behind them, along the 12-20 mile (18-30 km) passage of the Roman column, lay thousands of their dead. During the night, the barbarians stormed the Roman camp and tore the breastwork to pieces. Varus fell on his sword before the last legion line protecting him was overwhelmed.

Probably due to premature looting by the tribesmen, a sizable Roman contingent managed to fight its way out. At first, it seemed that the survivors eluded any pursuer, but then the path ahead narrowed with the marsh on one side and an earth embankment on the other. A wall of stakes and interlaced branches topped the embankment and behind it more barbarians waited. The Romans desperately tried to break through but were repulsed. Fleeing into the marsh, all but a handful of were hunted down.

THE EMPEROR ABANDONS THE CONQUEST OF GERMANIA

Arminius addressed his victorious men and mocked the Romans. The tribesmen took terrible vengeance on the captured Romans, torturing and sacrificing their victims while slavery awaited the remainder. As an illustration of his own power, Arminius sent Varus' head to Maroboduus, the mighty King of the Marcomanni who dwelt in the area of today's Czech Republic.

Arminius next targeted the Roman fort of Aliso on the Lippe, where he displayed the heads of slain legionaries to the defenders. The camp commander answered with a volley of arrows, and though Arminius assaulted the camp, he could not take it. During a stormy night, the Romans managed to break out but abandoned the accompanying civilians to the enemy.

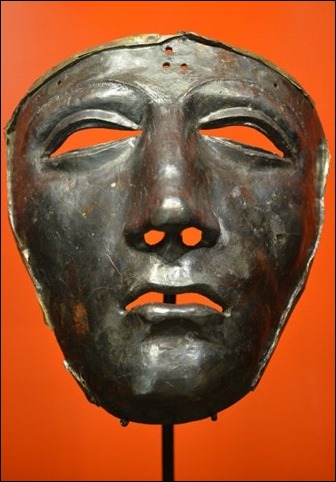

Kalkriese Face Mask

News of the destruction of three legions reached Emperor Augustus along with the head of Varus, courtesy of Maroboduus. An irate Augustus shouted, "Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions" ( Suetonius , The Twelve Caesars, II. 23). In light of the disaster in the Teutoburg, the Clades Variana, Augustus abandoned the conquest of Germania. Tiberius conducted minor offensives into Germania in 10 and 11 CE and then returned to Rome. With the elderly Augustus of failing health, Tiberius needed to ensure his own succession and so left behind his nephew Germanicus Julius Caesar to command the two armies guarding the Rhine frontier.

ARMINIUS VS. GERMANICUS

Germanicus was only a few years younger than Arminius and in many ways his Roman counterpart. In the aftermath of Augustus' death and Tiberius' succession, the legions of Germania Inferior (the lower Rhine) revolted. Germanicus put down the rebellion, having to pay the legions to stand down. He channeled the frustration of the legionaries against the Germanic tribes, to avenge the Clades Variana. Germanicus started off in 14 CE by massacring Marsi villages and then fending off a dangerous tribal counter-attack.

Arminius meanwhile was faced with a belligerent Segestes, who redeclared himself for Rome. Early in 15 CE, Arminius besieged Segestes' stronghold but was forced to retreat when Roman legions came to Segestes' aid. Segestes and his family were escorted to the safety of the Roman forts on the Rhine. Among them was Thusnelda, who against her father's wishes had married Arminius and was carrying his child. Tacitus relates Arminius' reaction to the loss of his pregnant wife:

Arminius, with his naturally furious temper, was driven to frenzy by the seizure of his wife and the foredooming to slavery of his wife's unborn child. "Noble the father," he would say, "mighty the general, brave the army which, with such strength, has carried off one weak woman. Before me, three legions, three commanders have fallen. Let Segestes dwell on the conquered bank...one thing there is which Germans will never thoroughly excuse, their having seen between the Elbe and the Rhine the Roman rods, axes, and toga. If you prefer your fatherland, your ancestors, your ancient life to tyrants and to new colonies, follow as your leader Arminius to glory…" (Tacitus, Annals, I.59)

Arminius' emotional appeals further unified and roused the tribes. His powerful uncle Inguiomerus finally joined the war against Rome.

Germanicus' next offensive was an all-out-assault on the Bructeri, involving four legions, 40 additional cohorts and two mobile columns. The lands were devastated, one of the legion eagle standards lost in the Teutoburg was recovered, and the site of the Varus disaster was found. Burying all the bones of their fallen countrymen proved too great a task for even the legions.

Seeking vengeance, Germanicus advanced east toward the Cherusci. Outnumbered, Arminius fell back into the wilderness.Arminius lured the Roman cavalry into a deadly ambush in a swamp, but the legions came to the rescue in the nick of time.Short on supplies, Germanicus broke off the campaign and with four legions returned to his fleet on the Ems. The other half of the army, commanded by Aulus Caecina Severus, returned via the old Roman land route known as the 'Long Bridges' first pioneered by Lucius D. Ahenobarbus 18 years ago.

The 'Long Bridges' led through swampy ground, perfect for ambushes, which Arminius was quick to exploit. Arminius struck at Caecina's column while it was repairing a causeway. In a harrowing battle, Caecina was barely able to lead his army into a defensive position. The next morning, Arminius personally spearheaded the attack. He came close to inflicting a total defeat on Caecina when the tribesmen started looting. Caecina was able to fight his way out and find dry ground to entrench himself for the night. Arminius wisely wanted to wait until Caecina's army was again on the march and vulnerable. Inguiomerus, however, thought the Romans a beaten enemy and incited the overzealous chiefs and warriors into a night assault. Thinking the battle won, the tribesmen were overwhelmed and scattered when the Romans boldly sallied forth at the right moment. The defensive victory allowed Caecina to safely reach the Rhine.

Germanicus

In 16 CE Germanicus decided to alleviate his supply problems by embarking his entire army on a gigantic fleet of 1,000 ships.Arminius tried to retain the initiative by attacking a Roman fort on the Lippe, forcing Germanicus to delay his summer offensive and come to the rescue with six legions. Arminius was driven off, and Germanicus returned to the Rhine where he reinforced his army with Batavian cavalry from the Rhine Island, led by their chief Chariovalda. The Roman fleet sailed to the sea, east along the Mare Germanicum (North Sea) coast and up the River Ems. Disembarking, Germanicus led his army cross country, further east, towards the Weser and Cherusci territory.

Standing on the eastern bank of the Weser, Arminius came to face his brother Flavus, who was with Germanicus' army, across the river. A scar and empty eye socket disfigured Flavus' face. Arminius called across the water, taunting Flavus as to what Rome had given him for his disfigurement. Flavus proudly spoke of the battle, of rewards, and of the justice and the mercy of Rome. Arminius retorted with words of ancestral freedoms, the gods of the north, and their mother who was praying for Flavus to come back to their side. Each brother was deaf to the other. An enraged Flavus had to be physically restrained from plunging his steed into the water to fight his brother.

Arminius commanded over too few troops to seriously challenge Germanicus' river crossing, but his Cherusci ambushed the Batavians and slew their chief, Chariovalda. Falling back before Germanicus' column, Arminius gathered his army in the sacred wood of Hercules (the Roman name given to the German Donner and Scandinavian Thor ). With Inguiomerus at his side, Arminius spoke to his assembled warrior: "Is there anything left for us but to retain or freedom or die before we are enslaved?" (Tacitus, Annals, II. 15)

Out from beneath the great forest strode forth the tribal warriors. Before them, the ground sloped down towards the Idistaviso plain, skirted by a bend in the Weser River. There the Roman army drew up; cohort after cohort of auxiliaries and of eight legions. Germanicus himself rode up with two cohorts of Praetorian Guards. The two forces clashed on the plain in a fierce battle. Arminius slashed his way through the Roman archers but was beset from all sides by auxiliaries. Arminius' face was smeared in blood as his horse broke through and carried him to safety. The battle ended in a resounding Roman victory.Barbarian casualties were heavy, scattered across the plain and into the forest beyond.

Arminius had suffered a defeat but was far from finished. Tribesmen were still arriving, more than making good his losses. He would make another stand in what was the battle of the Angrivarii barrier; a vast breastwork marking the border between the Angrivarii and the Cherusci between the Weser River and a forest. The Germans fiercely defended the barrier and drew the Romans into a confusing forest battle. Roman siege engines at last burst through the barrier. In the forest, Roman shield walls pushed the tribesmen against a swamp to their rear. His wound still hampering him, Arminius was less active. Inguiomerus led the attack but was unable to prevent another Roman victory.

Map of Celtic and Germanic Tribes

Arminius had lost another battle but not the war. Roman casualties were severe, the legionaries and auxiliaries were worn out and their supplies were in all likelihood nearly exhausted. Disaster struck on the sea voyage home, a storm wreaking havoc on both ships and troops. Even so, Germanicus was able to muster enough troops to inflict a terror campaign upon the Chatti and Marsi.

Against Germanicus' protests, Emperor Tiberius decided to call an end to the fruitless and costly campaigns. There would be no resumption of the war in 17 CE. Germanicus was honored with a lavish triumphal march. Among the displayed captives were Arminius' wife Thusnelda and their toddler son, Thumelicus.

ARMINIUS THRIVES TO BECOME KING

Arminius now held sway over much of Germania, his only rival was Maroboduus, King of the Marcomanni. According to Tacitus, "the title of king rendered Maroboduus hated among his countrymen, while Arminius was regarded with favor as the champion of freedom" (Tacitus, The Annals, II. 88). As a result, the Langobardi and Semnones went over from Maroboduus to Arminius. Inguiomerus, however, joined Maroboduus.

Both Arminius and Maroboduus assembled their armies to meet in battle. In a pre-battle speech, Arminius boasted of his victory over the legions and called Maroboduus a traitor. Maroboduus, in turn, bragged that he held off Tiberius' legions, though in truth they had been diverted by the Pannonian rebellion. Maroboduus also falsely claimed that it was Inguiomerus who had brought about Arminius' victories. Both armies deployed and fought in Roman fashion, with units keeping to their standards, following orders, and keeping forces in reserve. After a hard fought battle it was Maroboduus who fled to the hills.His lands beset by other tribes, Maroboduus found asylum in Rome.

Arminius now had no rival in Germania. However, many tribesmen resented any authority and Arminius' ambitions to be their king. In 19 AD a Chatti chief came to Rome offering to poison Arminius. Rome refused, telling the chief that Rome took vengeance in battle and not by "treason or in the dark" (Tacitus, Annals, II. 88). Later that year, after tribal in-fighting that raged back and forth, Arminius was killed after being betrayed by his relatives. Tacitus left a poignant tribute to Arminius:

He was unmistakably the liberator of Germany. Challenger of Rome - not in its infancy, like kings and commanders before him, but at the height of its power - he had fought undecided battles, and never lost a war... To this day, the tribes sing of him. (Tacitus, The Annals, II. 88)

As a military leader, Arminius showed intelligence, bravery, and charisma. He understood both the limitations and advantages of his own men and of his enemy. Arminius made skillful use of local terrain to defeat what was a superior trained and equipped enemy. Arminius also used his Roman training to improve the battlefield tactics of his own troops. In battle, he personally led attacks and was able to unite the tribes even after suffering tactical defeats. Arminius' victory in the Teutoburg forest and his resistance to Germanicus kept the Germanic tribes free of Roman dominion. Centuries later, their freedom would make possible the emergence of the nations of Germany, France, and England .

Arretium › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Arretium (modern Arezzo) was an important Etruscan town located in the extreme north-east of Etruria in central Italy .Flourishing as a trade and manufacturing centre, Arretium managed to overcome its rivalry with Rome and continue as a prosperous town into the Imperial period. Although much of its ancient architecture has disappeared, one significant legacy from the Etruscan period is the magnificent bronze statue known as the Chimera of Arezzo, perhaps that culture's finest surviving art piece.

EARLY SETTLEMENT

Although human habitation of the site dates back to the Palaeolithic Period, Arretium was something of a late starter compared to other Etruscan sites which sprang up in the Villanovan Period (1100-750 BCE). Etruscan Arretium was established, rather, sometime in the 6th century BCE. Arretium prospered due to its geographical location at the junction of the Tiber River and Arno River valleys. The settlement was also situated near a break in the Apennine Mountains giving access for wider Etruria to the Adriatic coastal region of eastern Italy.

ETRUSCAN ARRETIUM

Prospering as a trading hub, the town also manufactured its own goods, particularly bronze works, pottery , and terracotta statues. The artists of Arretium produced perhaps the finest single surviving Etruscan artwork, the 'Chimera of Arezzo.' This 5th-4th-century BCE representation of the mythical part-lion part-goat part-snake creature, exquisitely cast in bronze, was miraculously found in a ditch in 1553 CE when new fortifications were being raised by Cosimo de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. It now takes pride of place in the National Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Etruscan Civilization

RELATIONS WITH ROME

Arretium had a troubled relationship with her powerful neighbour Rome. According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus , the town sided with the Latins during the 6th century BCE in their battles with the Roman king Tarquinius Priscus. Illustrating the ambiguous nature of Etruscan-Roman relations over the centuries, the Roman historian Livy states that Rome actually helped Arretium in 302 BCE, or at least its ruling aristocracy. The dominant Cilnii clan faced a popular uprising from an increasingly disillusioned lower class and called in Rome for help. A Roman force was sent but was attacked and badly mauled in an ambush. A second larger force, led by the dictator Marcus Valerius Maximus, swiftly restored order. Rome was beginning to show an alarming interest in Etruscan affairs.

Rusellae (modern Roselle) was sacked in 294 BCE, a stark warning of the futility of opposing Rome. According to Livy, the Etruscan towns of Volsinii , Perusia, and Arretium then negotiated a peace with Rome. The price for a 40-year truce was a huge 500,000 asses per city . The truce did not last very long as, in 284 BCE, Volsinii took advantage of an invading army of Gauls to join them and attack Arretium, then loyal to Rome. A relieving Roman army was defeated, but the next year the Romans, led by P. Cornelius Dolabella, won a decisive victory at the Battle of Lake Vadimo.

Minerva of Arezzo

During the latter half of the 3rd century BCE, Arretium was also attacked by Carthage . However, the city was an ally (albeit a passive one) of Hannibal during his attacks in Italy during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), despite previously promising loyalty to Rome and often acting as an important Roman base from which to launch attacks in northern Italy. In the complex and delicate situation of a foreign army in Italy and Etruscan cities of dubious allegiance, Rome attempted to ensure greater loyalty by taking a number of hostages from Arretium's ruling families. When the Romans won victory over Carthage, Arretium's lack of support was not forgotten and the city was made to pay compensation by way of thousands of pieces of bronze weapons and armour.

Arretium then seems to have settled down as a minor town within the burgeoning Roman empire . In the 2nd century BCE, part of its territory was redistributed to Roman veterans, but it did benefit from being the first stopping point on the via Cassiawhich went from Rome and crossed the Apennines to Aquileia . In the early 1st century BCE Arretium was made a municipium . The city then made the fateful decision to back the wrong side in Rome's civil war , supporting Gaius Marius .The victor, Sulla , made a colony and resettled his veterans at Arretium in 80 BCE; Julius Caesar was to do exactly the same before the century was out.

Having got over its initial problems with Rome's expansion, Arretium became a relatively prosperous Roman town in the early Imperial period, no doubt helped by the fact that Emperor Augustus ' great confidant, Gaius Maecenas, was a native of Arretium. Benefits included construction of an amphitheatre , theatre, forum, and Roman baths . The town also became noted as a major production centre for the Arretina terra sigillata pottery with its distinctive coral colour and which was exported widely throughout the Roman world. The town gradually slipped into obscurity from the 2nd century CE when Trajanmade the decision to connect the via Cassia directly to Florentia (Florence), thus bypassing Arretium and robbing it of its commercial traffic. The town would regain some of its former glory in the late Middle Ages, though, when it became an independent city-state once again.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS

As with other Etruscan towns that have since been built over in medieval times and which continued to be occupied today, the archaeology of ancient Arretium has met with difficulties. There are traces of fortification walls from the period. Two Etruscan sanctuaries on the outskirts of Arretium are indicated by the presence of votive offerings. One, the Fonte Veneziana (named after a fountain near one of the city gates), had some 200 items in a votive pit. They included bronze figurines of humans and animals (some with gold leaf decoration), pottery vessels, and anatomical plaques of eyes, arms, legs, and busts. The second deposit at Monti Falterona was a lake in use between the 6th and 3rd century BCE where offerings were thrown in such as arrow heads, nuggets of bronze, pottery fragments, and bronze figurines. Fine examples of the latter category are a bronze male head and a warrior statuette, both are now in the British Museum, London.

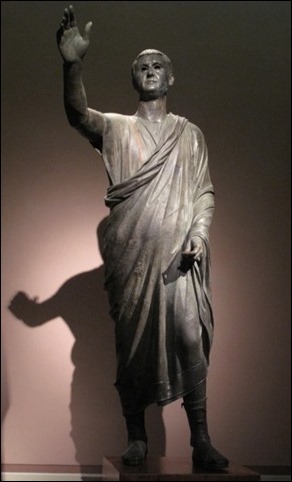

The Arringatore (Orator)

From the Roman period, there are remains of pottery workshops and some private housing. In addition, there is a lower course and several arches of the Roman amphitheatre still in situ, which gives an idea of the outline of the building.

Besides the magnificent Chimera already mentioned, other fine bronze statues are the ' Minerva of Arezzo' (3rd-1st century BCE), a 4th-century BCE statuette of two oxen and a ploughman, and a 1st-century BCE lifesize figure known as the Arringatore or 'Orator.' The latter work was discovered near Lake Trasimene in 1566 CE. The confident figure with arm raised in appeal and wearing a toga is perhaps the answer to the frequently asked question 'what became of the Etruscans ?': they became Romans.

Women's Work in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Women in ancient Egypt had greater rights than in any other civilization of the time. They could own land, initiate divorce, own and operate their own business, become scribes, priests, seers, dentists, and doctors. Although men were dominant and held the most important positions in society as a general rule, there is ample evidence of positions in which women had authority over men. Women's authority is evident in the early medical schools, women ruling the country without a male consort, female seers and physicians, early beer brewers and textile work managers, 'sealers' who safeguarded important records and objects, and most notably through the position of God's Wife of Amun .

New Kingdom Nobleman

Although women took care of the house, the extended family, and the children, they were also free - if they had the means - to leave these responsibilities to a servant or other female family member and seek work outside the home. Just as in the present day, a mother would raise her daughter according to her own values and lifestyle, and so a woman who prioritized housework and family would most likely produce a daughter who did the same; there was, however, no cultural stipulation against women working and holding a number of important positions.

Many women, in fact, who had been raised to be housewives turned those skills into high-paying jobs in the homes of nobility and the upper class. Others, who found housework fulfilling and whose husbands and sons provided amply, were content to care for the home and family. There is no difference between this social structure and that of many societies today with the exception that, in ancient Egypt, it was understood that the man was the head of the household and had the final word in decisions. Even so, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that men consulted with their wives regularly and that the marriage was seen as an equal partnership.

WOMEN AT HOME

Even though men held the place of authority, women kept the home functioning; whether they did so personally or supervised the work of servants. Even if a woman had a job outside the home, she was still responsible for maintaining it. Men are mentioned helping out with housework, but it was not their primary responsibility.

A wife and mother had many daily tasks beginning with the sunrise. She would need to wake her husband and children for work of school, maintain the family altar, prepare breakfast, clean up afterwards, tidy the house, make sure the home was free of pests and rodents, bring water from the well, ensure the stores of grain and other supplies were safe from contamination or pests, take care of the children if they were young, see to the needs of the other members of the extended family if they were elderly, feed the pets and make sure they were healthy, tend her personal garden, prepare the light afternoon meal, bake bread, brew beer, prepare the evening meal, take care of the weaving and sewing of clothing, sheets, blankets, and jackets, do the laundry, greet her husband and sons when they returned from work or school, serve dinner, clean up afterwards, feed the pets, put the young children to sleep, and prepare for bed.

Beer Brewing in Ancient Egypt

Some women also chose to work from home, and so, in addition to their daily chores, they also had to make time for their job.Work-from-home usually had to do with baking, brewing beer, sandal-making, basket-weaving, jewelry work, seal-making, textile weaving, and making charms and amulets.

There were usually many other women in the house one could call on to help with these chores since Egyptians lived with extended families. There was no marriage ceremony in ancient Egypt; a woman simply moved with her belongings to the house of her husband or her husband's family. A married couple could find themselves living with the husband's widowed mother, aunt, uncle, and cousins when they were first setting up a home. This situation meant little privacy but a number of people on hand to help with chores.

THE DOMESTIC CULT

Each home had its own altar which had to be kept clean and neat. People did not go to the temples in town to worship their gods but held private ceremonies and rituals in their houses. These altars would usually have an image or statue of a patron god or goddess and offerings would be placed there along with prayers making requests or giving thanks. This practice was especially prevalent in the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570-1069 BCE) and seems to have given rise to rituals which modern-day scholars refer to as the Domestic Cult or cults of domesticity.

These cults are suggested by archaeological discoveries and inscriptions which seem to indicate an elevated focus on appreciation of the feminine by focusing on female deities. Pretty much every home is assumed to have had a personal altar honoring the family's protective deities and ancestors, but these altars predominantly feature statuettes, images, and amulets of Renenutet (a goddess of protection in cobra form), Taweret (protective goddess of childbirth and fertility in hippo form), Bes(protective god of childbirth, children, fertility, and sexuality), and Bastet (goddess of women, children, hearth, home, and women's secrets). Scholar Barry J. Kemp notes how, in the worker's village at Deir el-Medina , there are paintings on the walls of the upstairs rooms which "supplied the focus for domestic feminity" (305). This cult is thought to have developed in response to the essential role women played in the daily life of the home.

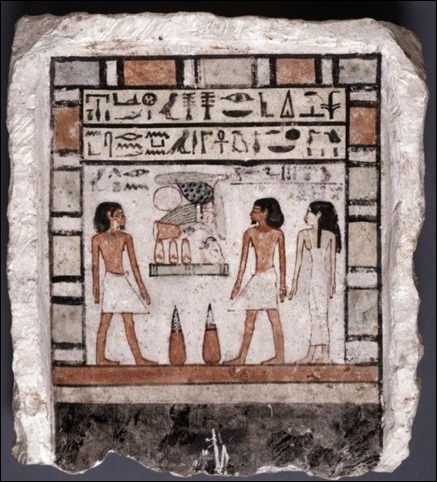

Stela of Renefseneb

Egyptologist Gay Robins notes how "the rites practiced in the domestic cult may have included offering food, libations, and flowers at the altar, as in other Egyptian cults" and that these rituals "suggest that women of the family had an important part to play" (163). While this is no doubt true, and there may well have been a "domestic cult," it is also possible that home altars during the New Kingdom simply celebrated the feminine aspect of divinity and protection more often than the masculine or that these kinds of altars have been found intact more than others.

It must be kept in mind that goddesses feature more prominently in Egyptian religious beliefs and stories than in those of other cultures and so it is hardly surprising to find home altars honoring the feminine. Bastet was not just a "woman's goddess" but one of the most popular deities in all of Egypt with both sexes, and the Cult of Isis became so popular that it would outlast every other Egyptian cult hundreds of years into the Christian era. The festivals of goddesses like Bastet, Isis, Hathor , and Neith were national events in which everyone participated just as they did for gods like Osiris , Ptah, and Amun.

WOMEN IN THE WORKPLACE

Egyptian culture empowered women from the time of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) through the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE) as evidenced by powerful female rulers such as Neithhotep in the First Dynasty through Cleopatra VII in the Ptolemaic Dynasty . There does not seem to have been the necessity of a particular cult in the New Kingdom to elevate the feminine since women had been participating almost equally in Egyptian society for thousands of years by then.

Egyptian Scarab Amulets

For example, from the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE) women held the position of 'sealers' which was among the most important jobs one could have. In the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) women were still in this position and the practice continued into the New Kingdom. Robins explains:

Sealing was one of the commonest duties of men throughout the bureaucracy because, in the absence of locks and keys, seals were used to safeguard property. A sealer carried the authorized seal with which to secure containers and storerooms against unauthorized entry. (118)

Women as sealers are evidence of their equality with men throughout Egypt's history. Even though, as in the home, men were considered the dominant authority figures, women could obviously hold the same position as long as they were not supervising and giving orders to men.

Even this point not does hold true in every era of Egypt's history, however, as it seems the female physician Pesehet (c. 2500 BCE) was a teacher at the medical school at Sais and the position of God's Wife of Amun, which became increasingly important in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt , was the female counterpart of the male High Priest. Female physicians would have seen both male and female patients, female seers would have interpreted the dreams and omens of males as well as females, and female dentists would have worked on alleviating the tooth pain of men as often as women.

WOMEN WERE THE FIRST BEER BREWERS & TEXTILE MANUFACTURERS IN EGYPT & CONTINUED TO MANAGE WORKSHOPS & BREWERIES.

Women also were the first beer brewers and textile manufacturers in Egypt and continued to manage workshops and breweries even when men took over the day-to-day operation of the business. Paintings, inscriptions, and statuary depict women working in as well as supervising over manufacture and distribution of goods. Women of means could also be the Mistress of the House meaning they owned their own land, produce, and means of harvest and distribution.

Those who had acquired particularly impressive skills in home management could make a living as Household Managers in the homes of the wealthy and nobility. These women were responsible for supervising the servants and making sure that every job was done to satisfaction as well as stocking the home with supplies and organizing official dinners and banquets. The title of Keeper of the Dining Hall was especially important to the upper-class nobility who entertained foreign diplomats and other dignitaries as the banquet prepared and served would need to be perfect in every way.

Women may have worked their way up to these kinds of positions from the lower status of maid, servant, or cook. Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley writes:

An Egyptian woman of good character could always find employment as a servant; the lack of modern conveniences, such as electricity and plumbed water, meant that there was a constant demand for unskilled domestic labour. A servant's wages were relatively cheap and most middle- and upper-class homes had at least one maid who could be trained in domestic skills while helping out with the more arduous household chores.(134)

Girls would enter the service at a young age, sometimes around 13, and if they proved themselves to be conscientious and loyal, could move up to a higher position. These women were vitally important to the maintenance of a home, and numerous letters and inscriptions make this clear. A common practice in ancient Egypt was writing letters to the dead asking for help in some matter. These often assumed a problem was being caused by some supernatural entity, usually an angry ghost or spirit whom the deceased could reason with or confront.

In one of these letters to the dead from a wife to her departed husband, the woman asks for his intercession on the part of a serving girl who is ill. She writes:

Can you not fight for her day and night with any man who is doing her harm, and any woman who is doing her harm? Why do you want your threshold to be made desolate? Fight for her again - now! - so that her household may be re-established and libations poured for you. If there's no help from you, your house will be destroyed;don't you know that it is this serving maid who makes your house amongst men? Fight for her! Watch over her!(Parkinson, 143)

A good servant was often considered a member of the family, and in some eras, a childless couple would adopt a servant as heir to ensure that their mortuary rites were performed correctly and that there would be someone to leave their estate to. In the above letter, the wife threatens the husband with cutting off his food and drink offerings ("why do you want your threshold to be made desolate?") if he does not intercede on the girl's behalf. This was a very serious threat because it was thought the dead required daily sustenance in the afterlife and it shows how much this serving girl meant to the author of the letter.

If a woman did not care for domestic work, she could be an entertainer. Women are recorded as musicians, singers, and dancers whether publicly or for temple rituals. Women could also be sacred singers who accompanied and assisted the God's Wife of Amun at Thebes and, in some instances, succeeded to that position. In order to become a God's Wife, the woman would need to know how to read and write and so, although a number of scholars claim that women lacked this skill, there seem to have been more of them than are credited.

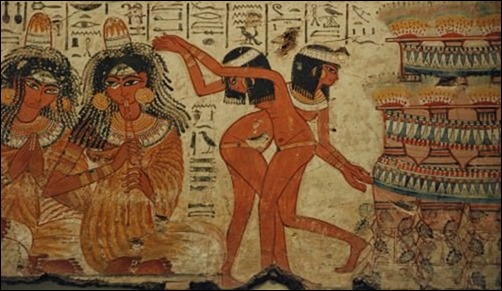

Ancient Egyptian Music and Dancing

Evidence for women's literacy comes from ostraca (clay pot shards) with notes on them relating to childbirth, children, dressmaking, laundry, and other domestic issues. These ostraca are the ancient equivalent of the modern day to-do list in some cases and, in others, are either protective charms or execration texts. Whatever form they take, there is no doubt they were written by women.

Women were denied high positions such as vizier and, save for some notable exceptions, the monarchy, but they certainly had greater opportunities for personal advancement and financial gain than their sisters in neighboring countries.Vrouwen waren essentieel cijfers als verloskundigen, zieners en tattoo artiesten - al is het onduidelijk of ze werden betaald voor deze diensten - maar ook een prominente plaats in de posities meestal in handen van mannen. De vrouwen van het oude Egypte waren grotendeels de directeuren van hun eigen lot, en in veel gevallen, de enige beperking om hun succes was hun eigen talent en verbeelding.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License