Armour in Ancient Chinese Warfare › Agesilaus II › Agni » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Armour in Ancient Chinese Warfare › Origins

- Agesilaus II › Who was

- Agni › Who was

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Armour in Ancient Chinese Warfare › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

With zinging arrows, powerful crossbow bolts, stabbing swords, and swinging axes all a staple feature of the Chinese battlefield, it is not surprising that soldiers sought to protect themselves as best they could with armour and shields. Leather tunics with metal additions, bronze or iron helmets, and shields of lacquered leather helped to deflect at least some of the missiles and slashing blades that came a soldier's way. Horses were similarly protected, and heavy cavalry with the horse and rider covered entirely in armour became a feature of later Chinese armies.

Chinese Terracotta Warrior

EARLY ARMOUR

The history and evolution of armour in Chinese warfare is difficult to ascertain with certainty, given its often perishable nature, but text descriptions and appearances in art, such as in wall paintings and on pottery figurines, along with surviving metal parts can help reconstruct major developments. Just who wore armour and when is another point of discussion. Military treatises of the Warring States period (c. 481-221 BCE) suggest that all officers of any level wore armour. The same sources contain references to commanders keeping armour in storage bags and distributing it to troops, but at least some of the ordinary conscripted infantry probably had to provide their own. This obviously depended on their means, and being farmers it is unlikely to have been a realistic possibility for most.The first armour in China was made from animal skins during the Neolithic period. These were probably not much adjusted for their new function and were likely more intended to impress than deflect weapons. From the Shang dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) leather was used to make tailored armour, and it would continue to be a popular choice for centuries. The most common source of leather was cowhide but the skin of buffalo and rhinos is also recorded (the Sumatran rhino was common in China prior to the 5th century BCE). The tanned and stiffened leather, sufficient to deflect bronze age weapons, was fashioned into two pieces to protect the chest and back of the warrior. Sometimes pieces of shell were used as an extra layer of protection, and there are remains of armour with high neck protectors. The armour was frequently painted, typically using red, yellow, white, black, and blue. Some were embellished with metal bosses and depictions of fearsome mythical creatures, tigers, or demon masks.THE MOST COMMON SOURCE OF LEATHER WAS COWHIDE BUT THE SKIN OF BUFFALO & RHINOS IS ALSO RECORDED.

SHIELDS

Shields were in use during the Shang period or even before. Early ones were larger, probably because the body armour of the time was less efficient than later versions. Some combined bronze plates and leather while more rudimentary versions would have been made from whicker, interlaced bamboo or reeds, wooden slats, or animal skins. The leather or layered cloth material was stretched over a wooden or bamboo frame and then lacquered to give extra strength without significantly adding weight. They came in two sizes, a smaller version for infantry and a larger one that could cover the height of a man for chariotriders. The infantry shield was held in one hand, and their remains in tombs suggest they had an approximate rectangle shape, curved slightly outward in the centre, had a single vertical handle centrally placed, and measured 70 x 80 cm.

Warring States Helmet

HELMETS

A soldier's head was protected by a helmet made first of rattan or leather and then, later, of bronze. They were typically of a spherical type covering the top of the ears, protected the back of the neck, and were topped by a simple and low crest. Some metal helmets have stylised projections and engravings similar to those used on shields. Bronze helmets were lined with a softer material to cushion blows and for comfort; they weigh on average 2-3 kilos. Helmets were only capable of deflecting light missiles and glancing blows from a sword, and enough skeletal remains evidencing wounds from arrowheads and swords suggests that armour, in general, was not particularly effective in earlier periods of Chinese warfare.ZHOU & QIN ARMOUR

By the middle of the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BCE) a more flexible armour was devised, made of small overlapping rectangles of leather held together using leather thongs, hemp cord or rivets, and made into the form of a tunic. Each piece of leather was hardened by tanning and lacquering. This type of armour is typical of the warriors of the Terracotta Army found in the tomb of Shi Huangdi, the first emperor of the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE). The terracotta warriors display seven different types of armoured tunic, some with extended flaps to protect the groin. An alternative to leather was to use small rectangles of bronze or a layered combination of bronze and leather. Naturally, too, many soldiers who could afford it adorned their armour with extra decorations designed to impress and made from precious metals, ivory, and rhinoceros horn.HAN ARMOUR

With the wider use of the crossbow and their increasing firepower, especially from the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) onwards, iron was increasingly used in body armour. Again, small plates were stitched or riveted together to form a semi-flexible tunic which also protected the outer upper arms. Iron was at the same time used to strengthen shields and to make helmets. Helmets of this period take on a hood-like shape with a hanging part to protect the neck but they still offered no protection for the face, even if there are references to iron face-masks in Han military treatises.

Chinese Cavalry Rider

Another development was to design armour for specific types of soldiers. The two or three soldiers within a chariot did not need any great mobility, and so their armour could be heavier and more cumbersome but with the benefit of offering greater protection. All of the body could be covered, provided the arms were left free to wield weapons such as lances and halberds (a mix of axe and spear). Infantry, meanwhile, had only short tunics and more basic leg protectors which allowed them to move quickly across the battlefield. Cavalry, which began to replace chariots from the 4th century BCE, were traditionally lightly armed with halberds and bow so that in order to move freely and fire from their primitive saddles while still on the move their clothing had to be light and unrestrictive.HORSE ARMOUR

The horse had, if any, only the limited protection of a hanging leather cover over its front below the neck and sometimes a tiger skin spread over its flanks. With the invention of the stirrup, a heavy cavalry became possible from the 4th century CE. These cataphracts had all-over body armour for both rider and horse and can be clearly seen in pottery figurines of the period. The great weight of such heavy cavalry impeded their use in practical terms and, consequently, there was a return to lighter and faster cavalry in the Tang period (618-907 CE), even if a small corps of gentlemanly knights continued well into the medieval period.LATER ARMOUR

During the Sui dynasty (581-618 CE) and the succeeding Tang dynasty periods, a new armour developed which became known as “cord and plaque”. Seen in pottery figurines of the time, the armour was composed of large iron plates joined by cords running down the centre and across the chest and linked to a cord belt, which probably helped distribute the weight away from the shoulders. Another popular type during the Tang was a long coat of armour made from hundreds of small metal plates and which hung down almost to the ankles. In medieval China, armour became even more ornate with intricately designed suits of armour made of fabric-covered riveted panels, armour which covered the tops of the legs for cavalry, and helmets made from multiple overlapping plates of iron or even sometimes engraved silver. Mail armour was used but rarely and, despite the arrival of gunpowder and firearms, Chinese armour remained remarkably traditional with leather still being commonly used for all types of warriors just as it had been for over two millennia.Agesilaus II › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Agesilaus II (c. 445 – 359 BCE) was a Spartan king who won victories in Anatolia and the Corinthian Wars but who would ultimately bring total defeat to his city through his policies against Thebes. When Sparta lost the crucial battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE, it brought an end to the city's long-held dominance of the Peloponnese. Agesilaus was one of the longest-serving and most powerful kings in Spartan history and, thanks to his friendship with the historian Xenophon, his reign is one of the best documented. He is also the subject of one of Plutarch ’s Lives biographies.EARLY LIFE & CAREER

Agesilaus was the son of Archidamus II and so a member of the Eurypontid line of Spartan kings. Agis II, the half-brother of Agesilaus, was the heir to the throne and so the latter was given the custom military education ( agoge ) of an ordinary male citizen. Plutarch informs us that Agesilaus was born with a lame leg but did not let this hinder his training. In 400 BCE, when Agis' son Leotychidas was looked over following rumours that his father was actually the Athenian general Alcibiades, Agesilaus was unexpectedly made king; an event facilitated by the powerful general Lysander, his lover ( erastes ) when a young man. Famously using patronage as a means to ensure loyalty from the Spartan elite, Agesilaus also managed to diminish the influence of the second Spartan kings from the Agiad line with whom he co-ruled. Despite his growing power, the king would gain a lasting reputation for his simple lifestyle and self-discipline, for as Plutarch said, 'it would have been hard to find a soldier who slept on a harder bed than the king' (38). Agesilaus was also known for his piety and the fact that he was one of the very few Greek rulers who campaigned abroad and remained uninfluenced by foreign customs and true to Spartan traditions.AGESILAUS WAS A GIFTED POLITICIAN & THE MOST POWERFUL MAN IN GREECE FOR MUCH OF HIS RULE AS SPARTAN KING.

CAMPAIGNS AGAINST PERSIA

Agesilaus' first prominent military role was an expedition to Anatolia where he was given the task of liberating the Greek citiesfrom Persian rule. This was the first time that a Spartan king had led an army in Asia and the first occasion when a king had commanded both the land and sea forces. Before setting off Agesilaus wanted to make a religious sacrifice at Aulis just like Agamemnon had done before the Trojan War but he was refused by the Thebans, archenemies of Sparta. This incident would add further fuel to Agesilaus' life-long hatred of Thebes. Victories against the Persian satraps Pharnabazus and Tissaphernes, notably at the battle of Sardis in 395 BCE, were interrupted when Agesilaus was recalled to mainland Greece to defend Spartan interests. This was perhaps just as well because Sparta had suffered a serious naval defeat at the battle of Knidos in 394 BCE. The Persian fleet had been commanded by Conon while the Spartans were led by the incompetent Peisander who was probably only given the command because he was a relative of Agesilaus.

Spartan Territory

CAMPAIGNS AGAINST CORINTH & THEBES

During the ensuing Corinthian Wars, Agesilaus won, albeit at great cost, the battle of Coronea in 394 BCE against a coalition force led by Thebes which included troops from Athens and Corinth. The two armies, in a contest that Xenophon, an eye-witness, described as 'quite unlike any other in our time' (4.3.15), clashed and both sides' right flank defeated their opposition's left flank. Then the Spartan and Theban hoplites turned on each other in a bloody battle in which Agesilaus was himself wounded several times. With the battle won, the Spartan king then spared the lives of a group of enemy soldiers who had sought refuge in a temple, he set up a victory monument and dedicated a tenth of the spoils at Delphi. More victories came between 391 and 388 BCE in the area around Corinth and Acarnania where Agesilaus demolished the fortifications of Corinth and devastated the countryside, uprooting every tree his army came across. However, the Thebans and their allies were ultimately defeated not by a land force but by a Persian-funded fleet led by the Spartan admiral Antalcidas. It was he who established the King's Peace (aka Peace of Antalcidas) which guaranteed a certain level of political autonomy to the defeated city-states. Agesilaus controversially ignored the terms of the peace treaty and established pro-Spartan oligarchies at Mantinea, Olynthus, and Phlius. The Spartan king then supported the occupation of Thebes in 382 BCE and the establishment of a garrison there by Phoibidas, which rankled the Thebans enormously. This action and the controversial acquittal of Sphodrias, who had been accused of trying to take over Athens' port the Piraeus and who just happened to be the father of the lover of Agesilaus' son, outraged many Greek city-states, and another anti-Spartan coalition was formed only this time with the financial backing of Persia. More battles followed and Agesilaus gained some victories in Boeotia in 378 and 377 BCE, but mighty Sparta was losing its grip on its own coalition the Peloponnesian League, and Thebes was about to enter its most dominant period in history.

Greek Hoplites

At a peace conference in 371 BCE, Agesilaus famously upset the Theban leader Epaminondas when he refused to accept that the latter was representing all of Boeotia and not just Thebes. War followed and Sparta was defeated at the battle of Leuctra in 371 when Epaminondas and his able general Pelopidas shocked the Greek world. According to Xenophon, Agesilaus was not at the battle as he suffered a relapse of his leg problem which had originally kept him from the battle of Tegyra in 375 BCE (which Sparta also lost) when a blood vessel had burst in his one good leg. Instead, at Leuctra the Spartan forces were led by the other Spartan king Cleombrotus. As a consequence of defeat, Sparta lost the region of Messenia in the Peloponnese and began a steady decline from which the city would never recover.CAREER AFTER LEUCTRA

While historians have blamed Agesilaus' aggressive policies and irrational hatred of Thebes for Sparta's decline, the king was not unpopular at home and continued to hold high office well into his eighties, defending the city from Theban attacks in 370 and 362 BCE. In between he had fought for Ariobarzanes, the Persian satrap in Anatolia in 364 BCE, and he performed a similar service for Nectanebis III in Egypt between 361 and 359 BCE. Both positions brought victories and helped increase the impoverished Spartan treasury. During the return home from Egypt, Agesilaus died at Cyrenaica in Libya in 359 BCE; his body was embalmed in wax and taken back to Sparta for burial. Agesilaus was a gifted politician and the most powerful man in Greece for much of his rule but perhaps his ambiguous character and portrayal in history is best summed up by Plutarch, 'he was too generous not to give credit to his enemies if they were in the right, but he could not bring himself to condemn his friends if they were in the wrong' (28). The Spartan had been a charismatic leader, had gained more political power than most of his predecessors, and been an effective field commander but perhaps was unlucky to have been king just at a time when Sparta suffered from a declining population and increasing unrest from its helot servile agricultural class. These two factors combined with the rise of an aggressive Thebes intent on creating its own empire meant that Agesilaus oversaw the end of mighty Sparta as one of Greece's superpower states.Agni › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

AGNI & VARIOUS FIRES

Agni is the son of the Celestial Waters and that element is closely connected with fire which is thought to be carried down to earth within rain. From there fire is drawn up by vegetation and so when two sticks are rubbed together fire appears. Agni is also responsible for lightning which is born from the god's union with the cloud goddess. Another fire Agni is associated with is the funeral-pyre; in this role he leads the dead to their final judgement by Yama, ruler of the Underworld.Agni is perhaps most closely associated with sacrificial fires where he is thought to carry the offerings of humans to the gods.According to various myths, Agni was at first afraid to take on this duty as his three brothers had been killed already whilst performing the task. Consequently, Agni hid in the subterranean waters but, unfortunately, fish revealed his hiding place to the gods. As a result Agni cursed them so that fish would become the easy prey of men. In another version it is frogs, then elephants, and then parrots which reveal Agni's attempts at hiding and the god punished them all by distorting their speech ever after. The final hiding place of Agni in this version was inside a sami tree and so it is considered the sacred abode of fire in Hindu rituals and its sticks are used to make fires. Reluctantly taking up his duty again Agni did negotiate by way of compensation to always receive a share of the sacrifice he carried to the gods and he was given the boon of ever-lasting life. Agni appears in all forms of fire and even those things which burn well or have a certain lustre. In the Brhaddevata we are told that at one point Agni is dismembered and distributed among earthly things. The god's flesh and fat becomes guggulu resin, his bones the pine tree, his semen becomes gold and silver, his blood and bile are transformed into minerals, his nails are tortoises, entrails the avaka plant, his bone marrow sand and gravel, his sinews become tejana grass, his hair kusa grass, and his body hair becomes kasa grass which was used in sacrificial rituals. Over time Agni's importance as a god diminishes, a fact explained in the Mahabharata as due to his over-indulgence in consuming one too many offerings. In the Visnu Purana he is described as the eldest son of Brahma and Svaha is his wife.Together they had three sons, Pavaka, Pavamana, and Suchi who in turn had 45 sons which, including their fathers and grandmother, totals 49, the number of sacred fires in the Vayu Purana. Agni, according to one Rigveda hymn attributed to the sage Vasistha, also has a darker side. Similar in nature to the 'flesh-eater' demons, the raksasa, he has two wickedly sharp iron tusks and he devours his victims without mercy. However, when called upon by the gods, Agni destroys the raksasa with his flaming spears. This episode, when Agni becomes a servant of the gods, is illustrative of his fall from the pinnacle of the pantheon.AGNI IS PERHAPS MOST CLOSELY ASSOCIATED WITH SACRIFICIAL FIRES WHERE HE IS THOUGHT TO CARRY THE OFFERINGS OF HUMANS TO THE GODS.

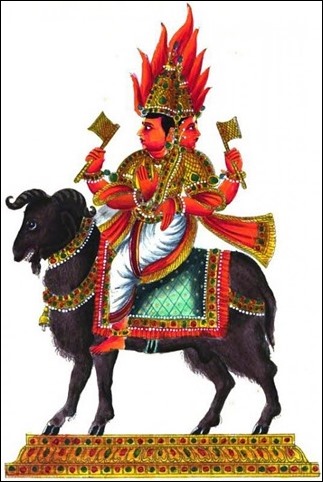

Agni

AGNI IN HINDU ART

In art, Agni is often depicted with black skin, two heads, four arms, and riding either a goat (the most commonly sacrificed animal) or a chariot drawn by red horses which has seven wheels, representing the seven winds. His two heads, which spout flames, are symbolic of his association with two types of fire: the domestic hearth and the sacrificial fire. He can have seven tongues which are used to lick up the ghee butter given as offerings. Typically he carries a fan (which he uses to build up fires), a sacrificial ladle, an axe, and a flaming torch or javelin. Agni may also be represented as the Garuda bird which carries the seed of life, the fire-bird which carries ambrosia to the gods, and the goat-headed merchant who represents the sacrifice made to the gods. In later Hindu art, Agni is also represented as one of the Dikpalas who were the eight guardians of the directions of space. Agni protects the south-east quarter, Purajyotisa.License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License