Constantine VI » Michael II » Trade in the Byzantine Empire » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions » Contents

- Constantine VI » Who was

- Michael II » Who was

- Trade in the Byzantine Empire » Origins

Ancient civilizations » Historical places, and their characters

Constantine VI » Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Constantine VI, also known as Constantine "the Blinded”, was emperor of the Byzantine Empirefrom 780 to 797 CE, although for most of his reign his mother, Irene the Athenian, ruled as regent. When Constantine did finally get a go at ruling in his own right, he was anything but successful. Deposed by his own mother, Constantine was infamously blinded by her in the royal palace and, as was the intention, he died from his injuries.

SUCCESSION & IRENE’S REGENCY

Constantine was the son of Leo IV (r. 775-780 CE) and when, in 780 CE, his father died of fever, aged just 30, Constantine became emperor Constantine VI. However, as the new emperor was still a minor at nine or ten years of age, his mother Empress Irene ruled as his regent, a role she performed until 790 CE. Irene had immediate problems and had to quash a rebellion led by the other sons of Constantine V (r. 741-775 CE) and half-brothers of Leo IV. Once that was dealt with, she ensured the loyalty of the palace entourage by dismissing any ministers and military commanders of questionable affiliation. To this end, she trusted two court eunuchs, in particular, Staurakios and Aetios.Irene attempted to further entrench her position by arranging a marriage alliance with the Franks and promising Constantine to Rotrude, the daughter of the Franks' king Charlemagne. For unknown reasons, Irene changed her mind, though, and in 787 CE she found an alternative wife for her son, one Mary of Amnia, a pious but slightly boring girl selected via the traditional “bride show” which Byzantine rulers organised for their offspring. The Frankish-Byzantine alliance would have been an intriguing one and joined the two halves of the old Roman Empire but the opportunity would come around again, as we shall see.

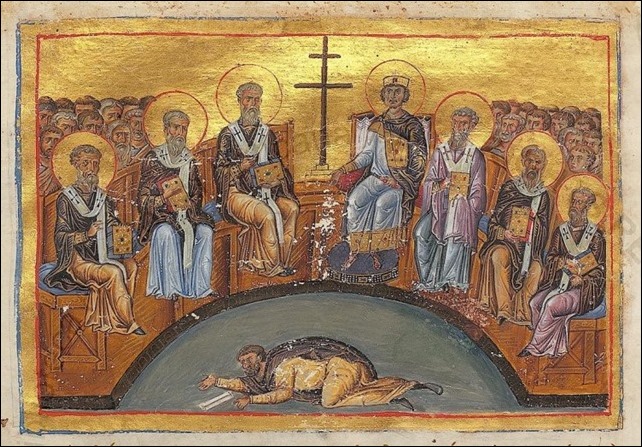

As ever, the borders of the Byzantine Empireneeded constant vigilance and defence. Irene enjoyed certain successes against both the Slavsin Greece and Arabs in Asia Minor. Closer to home, Irene convened a Church council in Constantinople in 786 CE which, despite initial opposition from members of the army who thought defeats on the battlefield were God’s punishment for the widespread veneration of icons, decreed an official end to iconoclasm, that is, the destruction of icons, a key feature of her predecessor’s reigns. The regent then went one step further and invited 350 bishops to the Seventh Ecumenical Council in September 787 CE which ruled to restore the orthodoxy of the veneration of icons in the Christian Church.IRENE MADE IT BE KNOWN THAT SHE INTENDED TO RULE ABOVE HER SON CONSTANTINE NO MATTER HOW OLD HE WAS.

Empress Irene

IRENE’S EXILE

Traditionally, a Byzantine monarch took their place on the throne when they reached 16 years of age and the regent gracefully stepped aside. Not so for Irene, the first ominous sign being the removal of Constantine’s face from the imperial coinage. When Irene made it be known that she intended to rule above her son Constantine no matter how old he was, many of those who opposed the restoration of icons, saw the dangers to the empire’s army strength Irene’s purges had threatened, and who believed Constantine had the rightful claim to the throne alone, rallied around the young emperor. Irene responded by executing seven dissenting generals and throwing her son in prison, but by 790 CE both the army and an anti-Irene mob came to Constantine’s support, stormed the prison, and released him. Fortunately for the young emperor, the army still contained many iconoclasts, and many had refused to swear loyalty to Irene alone on religious grounds.Now 19 years of age and keen to remove his interfering mother once and for all from state affairs, Constantine banished her from court along with her closest advisors while he engaged as his own advisor Michael Lachanodrakon, the influential general and governor of the Thrakesion region of the empire. After a decade in the shadows, Constantine took his rightful place at the apex of Byzantine government.

CONSTANTINE AS EMPEROR

Unfortunately, the young emperor was not actually up to the task of ruling. Serious and immediate defeats against the Bulgars and a shameful truce against the Arabs did nothing to aid his popularity. Even on the battlefield, where an emperor might gain some admirers for heading his own troops, Constantine’s cowardice had been revealed as he panicked and fled before the enemy. Now, back at court, conspiracies were rife. One led by Constantine’s uncle Nikephoros was quashed, and the emperor blinded the ringleader in an all too familiar act of imperial Byzantine brutality. Constantine then ordered the tongues of all four of his uncles to be torn out. The emperor then created another problem when he blinded Alexios Mousele the droungraios tes viglas or Commander of the Imperial Watch, an act which sparked off yet another rebellion, this time in the province of Armeniakon in northeastern Asia Minor.Leo IV & Constantine VI

Irene was not to be so easily ushered to the wings of power, either, and she returned to the court in 792 CE, invited by her son as a last-ditch attempt to restore some order to his reign. In effect, they ruled jointly for the next five years, but Irene soon began to plot against her son. Significantly, Constantine could no longer call on the support of Michael Lachanodrakon, the general having been killed that year while campaigning against the Bulgars. The army was all too unimpressed with the young emperor, and his popularity plummeted even further when he began to blame his soldiers for their defeats, taking the ill-advised action (cunningly suggested by Irene, of course) of tattooing the word “traitor” on the faces of 1,000 of them.A final crushing blow to Constantine’s ambitions was the protests following his divorce from Maria and subsequent marriage to his mistress Theodote, the so-called Moechian Controversy, in 795 CE. To make matters worse, the couple had a son 18 months later. Two monks were especially vociferous in their outrage at the emperor’s behaviour as head of the Church, Plato of Sakkoudion and Theodore of Stoudios, who both claimed that his divorce was illegal and so in marrying again the emperor had committed adultery. The emperor had lost the support of the one group he could always depend on; the iconophiles. Constantine’s unpopularity with his people and the Byzantine establishment meant that he had no friends left to block his removal from power by his own mother.A FINAL CRUSHING BLOW TO CONSTANTINE’S AMBITIONS WAS THE PROTESTS FOLLOWING HIS DIVORCE FROM MARIA & SUBSEQUENT MARRIAGE TO HIS MISTRESS.

DEATH & IRENE AS EMPRESS

In 797 CE, when Irene took back the throne for herself, she had her son detained while out riding and, on 15 August, had him blinded, doing so in the same purple chamber of the palace in which he had been born. The Porphyra room was a powerful symbol of an emperor’s legitimacy and right to rule, and, therefore, the act was as bold a statement as possible of Irene’s intent, not to mention her callousness. There was not going to be another rebellion against her rule. Constantine died shortly afterwards, almost certainly as a result of his injuries, which were intended to kill not maim. With his heir having already died earlier the same year, Irene had now dealt with all of her challengers. Thereafter, Irene is referred to in official state records as basileus, emperor, and not as empress, the first woman to so rule in her own right.Irene, as unpopular as ever and now infamous for her actions towards her son, would not reign for long. Hefty tributes to the Arabs in order to stave off further incursions into Byzantine territory made a serious dent in the state treasury and the constant whiff of rebellion around the palace meant that Irene’s position was precarious. Then, in 802 CE, there was the last straw. Irene attempted a marriage of alliance with Charlemagne, now the newly declared Emperor of the Romans in the west. It simply would not do, though, for a Byzantine emperor to marry an illiterate barbarian (as the Byzantines thought of him) and the nobles convened in the Hippodrome of Constantinople to declare that Irene must be removed from office. Exiled to a monastery on Lesbos, she was succeeded by Nikephoros I (r. 802-811 CE), one of the Empress’ former finance ministers. Irene died within a year of losing the throne she had loved so much and clung onto for so long. Meanwhile, the empire stumbled on, still trying to regain its former glory but without very much success.

In a bizarre postscript, Constantine VI did, in a sense, later return from the dead in the guise of the usurper Thomas the Slav, who led a rebellion against emperor Michael II (r. 820-829 CE) between 821 and 823 CE. Thomas, to add legitimacy to his otherwise spurious claim to the Byzantine throne, spread about the story that Constantine VI had not, in fact, died when his mother Irene had blinded him but had managed to escape Constantinople and he was the very same person, dead set on getting back what was rightfully his. Thomas even had himself crowned emperor in Antioch, but it was all to no avail and his rebellion was quashed by Michael in 823 CE.

Michael II » Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Mark Cartwright

Michael II the Amorion, also known as Michael “the Stammerer”, was emperor of the Byzantine Empire between 820 and 829 CE. He founded the short-lived Amorion dynasty, named after his hometown in Phrygia, which would last until 867 CE. Surviving the major rebellion and siege of Constantinople led by Thomas the Slav, the emperor’s reign witnessed little else of success as the empire continued to crumble at its edges, with Sicily and Crete being notable losses.

SUCCESSION

Michael hailed from the strategically important city of Amorion (aka Amorium) in Phrygia, the capital of the military province of Anatolikon. Amorion protected the road from the Cilician Gates to the Byzantine capital Constantinople. Michael was a seasoned military commander in the Byzantine army and is described by the historian J. J. Norwich as "a bluff, unlettered provincial…of humble origins, with an impediment in his speech" (131). Michael rose to become Emperor Leo V the Armenian’s (r. 813-820 CE) right-hand man and was given the top job of Commander of the Excubitors, an elite regiment of the palace guard.Michael wanted rather more, though, and he took his chance and seized the throne in 820 CE in one of the most shameless and shocking episodes of self-promotion the Byzantines had witnessed, and they had seen a good few over the centuries. Michael’s supporters did not go for the quiet stab in the back down a dark alley assassination plot but murdered the reigning emperor right in front of the altar of the Hagia Sophia church, and on Christmas day of all days.

Actually, Michael and his supporters had been rather pushed into this dramatic action as he had just been condemned to death by Leo the day before - the novel method of execution decided upon involved tying the victim to an ape and putting the pair into the furnaces which heated the palace baths (quite what the ape had done to deserve his sentence is unclear). Michael, accused of plotting a rebellion and confessing his guilt, had been due to be executed on Christmas Day but Leo was persuaded by his wife Theodosia that such an act was not a particularly appropriate one for that special day and so the sentence was postponed to the day after. The decision was a fateful one, and Michael was saved from this ignominious end by his supporters who disguised themselves as a choir of monks and butchered the emperor. Leo proved not such an easy target, though, and he defended himself, according to legend, with a large metal cross for an hour before finally succumbing to the assassins who lopped off his head.MICHAEL WAS SAVED FROM EXECUTION BY HIS SUPPORTERS WHO DISGUISED THEMSELVES AS A CHOIR OF MONKS & BUTCHERED THE EMPEROR.

The Byzantine Empire in the mid-9th century CE

Michael II was immediately released from his prison and crowned, still wearing his chains around his ankles as no one could find the keys. Meanwhile, Leo’s mutilated body was dragged naked around the Hippodrome of Constantinople for public ridicule. Leo’s wife and children were exiled to the Princes’ Islands where the four sons were subsequently castrated. The Isaurian dynasty, which had had eight emperors, one empress, and ruled since 717 CE, was swept away, and the Amorion dynasty begun.THOMAS THE SLAV

Fortunately, Michael benefitted from Leo V’s defeat of the Bulgars in 814 CE and the sudden death of their leader, the Khan Krum. A 30-year peace allowed both the Bulgars and Byzantines to concentrate on other threats. Unfortunately, though, almost immediately, Michael had to defend his throne against a rival usurper, the fellow general Thomas the Slav (although actually from Gaziura in Asia Minor). Rallying support from those outraged at Leo V’s murder and backed by all but two of the provinces (themes) in Asia Minor, Thomas led a damaging three-year rebellion against Michael’s regime.The charming and wily Thomas made sure he appealed to just about every group who might have a grievance against the emperor - the overtaxed poor, those in the Church who opposed Michael’s (albeit moderate) stance against the veneration of icons in the Byzantine Church, and even those old followers of the deposed Constantine VI (r. 780-797 CE) - bizarrely, Thomas even claimed to actually be the blinded Constantine VI and had himself crowned as such in Antioch. Thomas, unknown to the majority of his followers, was actually receiving cash from the Caliph Mamun (r. 813-833 CE) and in return, he would probably have turned Constantinople into a fiefdom of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Crucially, Thomas could also call on the naval fleet of the province of Kibyrrhaiotai, located along the southern coast of Asia Minor, and the height of the crisis came when Thomas besieged Constantinople from the sea in December 821 CE. Heavy winter storms saw off the initial attacks, and then, in the longer term, the massive fortifications of the city, the Theodosian Walls, and the judicious placement of catapults and mangonels ensured the capital resisted Thomas' own catapults and siege engines.

Thomas the Slav Attacks Constantinople

The emperor was also fortunate to have the Bulgar Khan Omurtag (r. 814-831 CE) as an ally. Omurtag’s army helped to finally break the stalemate and end the siege in March 823 CE. Thomas' army was crushed on the plain of Keduktos near Heraclea and swept up by Michael’s force riding out from the capital. Thomas fled the scene and, with a mere handful of followers, barricaded himself in the fortified town of Arcadiopolis. Michael pursued his foe and laid siege to the town, nicely reversing the roles of attacker and defender. Thomas held out for a few months, but he and his men were forced to eat their own horses to survive. Finally, in October 823 CE, Michael offered a pardon to the defenders if Thomas was handed over. Thus, the would-be usurper was captured and executed, first having his feet and hands cut off and then his body impaled on a stake.THERE WERE SIGNIFICANT DEFEATS AT THE HANDS OF THE ARABS IN BOTH CRETE & SICILY.

THE ERODING EMPIRE

Michael might have survived a siege at home and put down the greatest rebellion the Byzantine Empire had ever witnessed but farther afield events were anything but encouraging. There were significant defeats at the hands of the Arabs in both Crete and Sicily in 825 CE and 827 CE respectively. Crete, in particular, became a major problem for just about everyone in the Mediterranean as it turned into an impregnable base for pirates, while the city of Candia (Heraklion) developed into the biggest slave market in the region. Michael launched three separate attacks on the island between 827 and 829 CE but all failed to retake it. The loss of parts of Sicily would also have significant repercussions as the Arabs used it, like so many armies before and after them, as a landing stage to attack and conquersouthern Italy.RELATIONSHIP WITH THE CHURCH

Michael had been only a moderate iconoclast who did not take very much interest in the debate which some of his predecessors had fuelled by their persecution of those who venerated icons. He even pardoned such notable iconophiles as Theodore of Studium, and his moderate policies generally made him popular with both sides of the debate. One area which did ruffle some ecclesiastical feathers was the emperor’s second marriage. As an important representative of the Church, the ruler was not meant to remarry, but after Michael’s first wife Thecla died, he married Euphrosyne, the daughter of Constantine VI. To make matters worse, Euphrosyne was a nun. Nevertheless, Michael managed to get around the Church and the past vows of his betrothed to marry his new sweetheart, who, with her royal blood, also gave his reign and, more importantly, his heir, an air of legitimacy.DEATH & SUCCESSOR

Michael died of natural cause in October 829 CE and he was succeeded by his son Theophilos (r. 829-842 CE), then aged just 25. It was Theophilos who would continue where Leo V had left off to vehemently continue the destruction of icons in the Church and the persecution of those who venerated them. Theophilos was succeeded by his son Michael III(r. 842-867 CE), the last of the Amorion emperors whose early reign was dominated by his regent mother Theodora.Trade in the Byzantine Empire » Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Mark Cartwright

Trade and commerce were essential components of the success and expansion of the Byzantine Empire. Trade was carried out by ship over vast distances, although for safety, most sailing vessels were restricted to the better weather conditions between April and October. On land, the old Roman road system was put to good use, and so by these two means goods travelled from one end of the empire to the other, as well as from far-away places such as modern-day Afghanistan, Russia, and Ethiopia. The bigger cities had thriving cosmopolitan markets, and Constantinople became one of the largest trading hubs in the world where shoppers could stroll down covered streets and pick up anything from Bulgarian linen to Arabian perfumes.Constantinople

ATTITUDES TO TRADE

The attitude to trade and commerce in the Byzantine Empire had changed very little since antiquity and the days of ancient Greece and Rome: the activity was not regarded highly and considered a little undignified for the general landed aristocrat to pursue. For example, emperor Theophilos (r. 829-842 CE) famously burned an entire ship and its cargo when he found out that his wife Theodora had been dabbling in commerce and had financial connections with the vessel. This attitude may explain why Byzantine chroniclers often avoid the subject entirely. Indeed, in Byzantine art and literature, traders, merchants, bankers and money-lenders who had tried to cheat their clients were often portrayed as inhabiting the lower levels of Hell.There was also a general mistrust of traders and entrepreneurs (who could be both men and women) by both the general populace and the authorities. Emperors, therefore, were often particular in enforcing such matters as the standardisation of weights and measures, and, of course, prices. Heavy goods were scrupulously weighed using steelyards and weights in the form of a bust of either the emperor or the goddess Minerva/Athena. Smaller goods such as spices were measured out using a balance with weights made of copper-alloy or glass. To minimise cheating, weights were inscribed with their representative weight or equivalent value in gold coinage and regularly checked.

CUSTOMS STATIONS WERE DOTTED ALONG THE FRONTIERS & MAJOR PORTS OF THE EMPIRE WITH TWO OF THE MOST IMPORTANT BEING AT ABYDOS & HIERON.

STATE INVOLVEMENT

Perhaps because of these attitudes to trade as a slightly less than respectable profession, the state was much more involved in it than might be expected. Unlike in earlier times, the state played a greater role in trade and the provisioning of major cities, for example, which was rarely left to private traders. Trade operated through a variety of hereditary guilds with merchants who transported the goods (navicularii) being subsidised by the state and subject to significantly reduced duties and tolls. Duty on imported goods was collected by state-appointed officials known as kommerkiarioiwho collected duties on all commercial transactions and who issued an official lead seal once goods had been through the system. To limit the possibilities for corruption, the kommerkiarioi were given one-year posts and then moved elsewhere.Customs stations were dotted along the frontiers and major ports of the empire with two of the most important being at Abydos and Hieron, which controlled the Straits between the Black Sea and the Dardanelles. There must have been a good deal of smuggling but measures were taken to counter it such as a 6th-century CE treaty between the Byzantines and Sassanids which stipulated that all traded goods must pass through official customs posts. Records were scrupulously kept, too, most famously the Book of the Prefect in Constantinople, which also outlined the rules for trade and trade guilds in the city.

Nomisma Coin of Basil II

Other examples of state intervention in trade include the provision made for loss or damage to goods transported by sea. The Rhodian Sea Law (7th or 8th century CE) stipulated that, in such a case, merchants received a fixed compensation. The state also ensured that no goods useful to an enemy were permitted to be exported - gold, salt, timber for ships, iron for weapons, and Greek Fire (the secret Byzantine weapon of highly inflammable liquid). Neither was the prestigious silk dyed with Tyrian purple permitted for sale abroad.Another area of close state supervision was, of course, coinage. Copper, silver, and gold coins were minted and issued carrying images of emperors, their heirs, the Cross, Jesus Christ, or other images related to the Church. Although the state minted coins primarily for the purpose of paying armies and officials, the coinage did filter down and through all levels of society. Coinage - in the form of the standard gold nomisma (solidus) coin - was also necessary to pay one’s annual taxes. When there were fewer wars and so fewer soldiers and suppliers to pay for or when the tentacles of the local state bureaucracy declined in the 7th and 8th century CE, coins could become scarce and barter had to be resorted to in the provinces, especially.

Byzantine state control of trade was hit by the Arab conquests from the 7th century CE. Cities, too, were in decline and ever-more self-sufficient while shipping became increasingly the domain of private traders. When a greater stability in the Mediterranean allowed for a resurgence in wider trade networks from the 10th century CE, it would be the Italian states which seized the opportunity to reap profit from the transport and sale of goods from one end of the known world to the other. Great merchants such as the Venetians were even given their own facilities and preferential regulations and duties at Constantinople. At first, this was in return for naval aid in Byzantine wars, but steadily the presence of Italian merchants (from Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa, and Venice) on the wharfs of the capital would become a permanent fixture. Constantinople, thus, could boast the most vibrant market in Europe with merchants from Syria, Russia, Arabia and many other places forming a semi-permanent cosmopolitan residency. Quarters sprang up in the city where Jews built synagogues, Arabs built mosques, and Christians their churches.

The Byzantine Empire in the mid-9th century CE

TRADED GOODS

The great traded goods of antiquity continued to be the most commonly shipped in the Byzantine Empire of the medieval period: olive oil, wine, wheat, honey, and fish sauce. Likewise, the terracotta amphora remained the storage vessel of choice. The design of amphorae changed depending on the location of their manufacture, although handles became significantly bigger from the 10th century CE. The contents were carefully labelled with either stamped inscriptions on the sides or clay tags added. Byzantine amphorae have been found across the Mediterranean and in ancient Britain, the Black Sea, the Red Sea, and the Arabian Sea areas. Not until the 12th century CE would the amphorae be challenged and surpassed in use by the wooden barrel.Other goods which were traded between regions included cattle, sheep, pigs, bacon, vegetables, fruit, pepper and other spices, medicines, incense, perfumes, soap, wax, timber, metals, worked gemstones, lapis lazuli (from Afghanistan), glass, ivory (from India and Africa), worked bone, flax, wool, textiles, linen (from Bulgaria), fur (from Russia), silver plate, enamels, amber (from the Baltic), bronze vessels, and brass goods (especially buckets and decorated doors panels largely destined for Italy). The slave trade, with slaves often supplied from Russia, continued to be important, too.BYZANTINE AMPHORAE HAVE BEEN FOUND ACROSS THE MEDITERRANEAN & IN ANCIENT BRITAIN, THE BLACK SEA, THE RED SEA & THE ARABIAN SEA AREAS.

Pottery tableware was another common part of any ship’s cargo as indicated by shipwrecks. Slipped red-bodied ceramics with stamped or applied decoration were common until the 7th century CE and then slowly replaced by finer wares which were lead-glazed, white-bodied and then red-bodied from the 9th century CE. Decoration, when present, was impressed, incised, or painted. Constantinople was a major production centre for white-bodied ceramics and Corinth produced a large quantity of red-wares from the 11th century CE.

Silk was first introduced from China but imported raw silk was eventually replaced by silk produced on mulberry farms (the food of the silkworm) in Phoenicia and then Constantinople from 568 CE. The silk factory at the Byzantine capital was under imperial control, and the five silk guilds were under the auspices of the Imperial Prefect of the city. Other notable silk-producing sites within the empire included southern Italy, GreekThebes and Corinth.

Amphorae

Marble was always in demand across the empire as it was used by those who could afford it for buildings, flooring, church altars, decoration, and furniture. The basic grey-white marble which became the staple of any Byzantine architect’s project was quarried in large quantities from the island of Proconnesus in the Sea of Marmara (up to the 7th century CE) while more exotic marble came from Greece, Bithynia and Phrygia. Shipwrecks provide evidence that marble was worked before it was shipped to its final destination. Many ancient monuments, especially pagan ones, across the Mediterranean were also plundered for whatever useful marble bits and pieces could be reused and shipped elsewhere. Cyzicus in the Sea of Marmara became a noted centre of marble production and recycling from the 8th century CE.MARKETS & SHOPS

Ordinary citizens could purchase goods in markets which were held in dedicated squares or in the rows of permanent shops which lined the streets of larger towns and cities. Shops usually had two floors - one on street level where the goods were manufactured, stocked and sold, and a second floor where the shopkeeper or artisan and their family lived. Shoppers were protected from the sun and rain in such streets by collonaded roofed walkways, which were often paved with marble slabs and mosaics. Some shopping streets were pedestrianised and blocked to wheeled traffic by large steps at either end. In some cities, the shopkeepers were expected to maintain lamps outside their shops to provide street lighting. Just as today, shopkeepers tried to spread their wares out as far as possible to catch the casual shopper, and there are imperial records complaining about the practice.One final highlight of the shopping calendar was the festivals and fairs held on such important religious dates as saint’s birthdays or death anniversaries. Then churches, especially those with holy relics to attract pilgrim visitors from far and wide, became the centrepiece of temporary markets where stalls sold all manner of goods. One of the largest such fairs was at Ephesus, held on the anniversary of Saint John’s death. Typically, the 10% sales tax collected by the state kommerkiarioi at such events was a tidy sum, according to one record as much as 100 lbs (45 kilos) in gold.

License

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License

![clip_image005[1] clip_image005[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhv_tXu0p9LGVn48PZ0WtDAEoaSATvmT_zQlS8pi61cjWA6blgtv4iMBjSPh1BZdzXurR1VZv_lgOeM4U9jR51K3BRCwr9-kF1jKp8yMStDv1CMrqwQLNcihZbeqZTQ_aDIECODJmvcHAQ/?imgmax=800)