Aristotle › Arjuna › Cosmetics, Perfume, & Hygiene in Ancient Egypt » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Aristotle › Who was

- Arjuna › Who was

- Cosmetics, Perfume, & Hygiene in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Aristotle › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Aristotle of Stagira was a Greek philosopher who pioneered systematic, scientific examination in literally every area of human knowledge and was known, in his time, as "the man who knew everything", and, later, as "The Philosopher" (so named by Aquinas who felt one needed no other). In the European Middle Ages he is referred to as "The Master" in Dante's Inferno . All of these epithets are apt in that Aristotle wrote on, and was considered a master in, disciplines as diverse as biology, politics, metaphysics, agriculture, literature , botany, medicine, mathematics, physics, ethics, logic, and the theatre. He is traditionally linked in sequence with Socrates and Plato in the triad of the three greatest Greek philosophers.

Aristotle was born in 384 BCE in Stagira, Greece , on the border of Macedonia. His father, Nichomachus, was the court physician to the Macedonian king and died when Aristotle was ten years old. His uncle assumed guardianship of the boy and, as a teenager, Aristotle was sent to Athens to study at Plato's Academy where he remained for the next 20 years. He was an exceptional student, graduated early, and was awarded a position on the faculty teaching rhetoric and dialogue. It appears that Aristotle thought he would take over the Academy after Plato's death and, when that position was given to Plato's nephew Speusippus, Aristotle left Athens to conduct experiments and study on his own in the islands of the Greek Archipelago.

ARISTOTLE'S WRITINGS, LIKE PLATO'S, HAVE INFLUENCED VIRTUALLY EVERY AVENUE OF HUMAN KNOWLEDGE PURSUED IN THE WEST AND THE EAST.

In 343 BCE Aristotle was summoned by King Philip II of Macedonia to tutor his son Alexander (who, of course, would become Alexander the Great ) and held this post for the next seven years, until Alexander ascended to the throne and began his famous conquests. The two men remained in contact through letters, and Aristotle's influence on the conqueror can be seen in the latter's skillful and diplomatic handling of difficult political problems throughout his career. Alexander's habit of carrying books with him on campaign and his wide reading have been attributed to Aristotle's influence as has Alexander's appreciation for art and culture.

Aristotle returned to Athens to set up his own school, The Lyceum, a rival to Plato's Academy. Aristotle was a Teleologist, an individual who believes in `end causes' and final purposes in life, and believed these `final purposes' could be ascertained from observation of the known world. Plato, who also dealt with final causes, considered them more idealistically and believed they could be known through apprehension of a higher, invisible, plane of truth he called the `Realm of Forms'. Aristotle could never accept Plato's Theory of Forms nor did he believe in positing the unseen as an explanation for the observable world when one could work from what one could see backward toward a First Cause. While Plato claimed that intellectual concepts of the Truth could not be gained from experience, Aristotle claimed that they could be and taught these precepts to his students at the Lyceum. Aristotle's habit of walking back and forth as he taught earned the Lyceum the name of the Peripatetic School (from the Greek word for walking around, peripatetikos ). His favorite student at the school was Theophrastus who would succeed Aristotle as leader of the Lyceum.

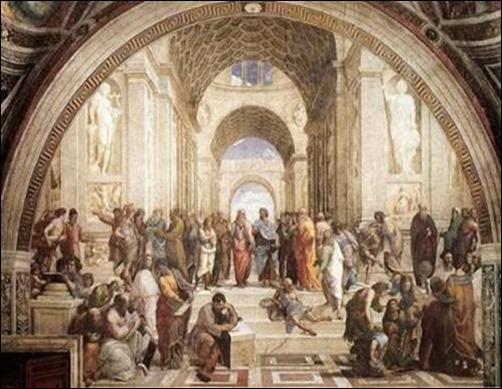

School of Athens

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, when the tide of Athenian popular opinion turned against Macedon , Aristotle was charged with impiety owing to his earlier association with Alexander and the Macedonian Court. With the unjust execution of Socrates in mind, Aristotle chose to flee Athens, "lest the Athenians sin twice against philosophy ", as he said, and died a year later in 322 BCE.

Aristotle's writings, like Plato's, have influenced virtually every avenue of human knowledge pursued in the west and the east.His Nichomachean Ethics (written for his son, Nichomachus, as a guide to good living) is still consulted as a philosophical touchstone in the study of ethics. He created the field and the study of what is known as `metaphysics', wrote extensively on natural science and politics, and his Poetics remains a classic of literary criticism.

Arjuna › Who was

Definition and Origins

Author: Cristian Violatti

Arjuna is one of the heroes of the massive Indian epic named “The Mahabharata ”, the longest Indian epic. He is the third of the five Pandava brothers, officially the son of king Pandu and his two wives Kunti (who is also known as Pritha) and Madri.However, we read in books 1 and 3 of the Mahabharata that the Pandava brothers are actually the offspring of different gods and the two wives of king Pandu.

MIRACULOUS CONCEPTION

When Kunti was a young girl, a priest granted her a curious gift: by the means of a secret sacred formula, she was able to summon up gods at will to beget children with her. By the time Pandu married Kunti, he had a curse on him: he had been condemned to perish if he ever engaged in sex. This was an obstacle to perpetuate his lineage, so Kunti's gift became very useful: Pandu and Kunti agreed on using her gift. She first summoned the god Dharma and conceived Yudhisthira. The second god summoned was Vayu and Kunti conceived Bhima. Finally, the god Indra was summoned, conceiving Arjuna. After this, Kunti taught the sacred formula to her co-wife Madri and she summoned the Ashvins , two Vedic gods, and conceived the twins Nakula and Sahadeva.

THE SEARCH FOR GLORY

In Indian tradition, archery is held as a highly respected battle skill and it is also considered an art. No wonder, then, that the bow and arrow are Arjuna's choice as a warrior. Like many heroes, Arjuna is not much of a family man: he has a tendency to go off on his own looking for action. A number of adventures happen to him when he goes into exile for thirteen years. He marries Draupadi, who is actually the wife of all five Pandava brothers, a very unique family structure not replicated elsewhere in Indian tradition.

He had quite a few adventures with the god Krishna . Interestingly enough, despite the fact that Krishna is not only a god but the reincarnation of the god Vishnu , Arjuna treats Krishna more like a peer instead of with the respect that a junior member of the family should feel for a supreme god. Forming a warrior pair with Krishna, Arjuna burns down the Khandava Forest, so it becomes suitable for building the Pandava capital city , Indraprastha, which is probably present-day New Delhi in India .

POSSIBLY THE MOST DRAMATIC EPISODE IN ARJUNA'S LIFE TAKES PLACE IN THE BHAGAVAD GITA.

Arjuna also travels to the world of the god Indra and on his way he fights against the god Shiva who assumes the form of a mountain man. Once in Indra's heaven, Arjuna spends ten years and he learns to dance.

The background of Arjuna's adventures relates to an episode in which two sets of cousins, the Pandavas and the Kauravas , are competing for the throne. Yudhisthira, the eldest of the Pandava brothers, loses his right to rule during a dice game. Tha Kauravas challenge Yudhisthira to take part in a dice competition where the dice are not only loaded but also handled by one of the Kauravas' uncle. Yudhisthira is not allowed to refuse the challenge, since he is a member of the Kshatriya caste (the warrior rulers caste), and it is against his dharma to withdraw once someone has challenged him directly. The passion of the game is so high, that he starts losing everything: possessions first, then his kingdom, and even the freedom of his brothers, his own freedom and, finally, the freedom of his wife, Draupadi. The situation gets very violent when Draupadi is dragged by the hair by one of the Kaurava brothers despite the protests that she is having her period. During the climax of the conflict, the cry of a jackal is heard in the court, and everyone present acknowledges it is a bad omen.

Dhritarashtra, the blind king, is overseeing this challenge and, moved by the brutality of the events, decides to grant three wishes to Draupadi. Her first wish is the freedom of Yudhisthira, her second wish is the freedom of the remaining four brothers, and she refuses to ask for a third wish. On explaining the reasons why she refuses her third wish, Draupadi replies, “greed destroys dharma ”. Finally, the blind king declares the game void and allows the Pandavas to depart. A deal is then agreed between Pandavas and Kauravas, by which the Pandavas will go into exile for thirteen years and after that period they will be allowed to return and reclaim the kingdom. Once the time is over, they come back, the Kauravas refuse to return the kingdom to the Pandavas and war inevitably follows.

Arjuna During the Battle of Kurukshetra

THE COSMIC VISION

Possibly the most dramatic episode in Ajuna's life takes place in the Bhagavad Gita, an ancient Indian text that became an important work of Hindu tradition in terms of both literature and philosophy , also known as the Gita , for short.

The setting of the Gita is during the Kurukshetra war, a major conflict between the Pandavas and the Kauravas fighting to control the kingdom and it is presented as a long conversation between Arjuna and Krishna, who is actually a reincarnation of the god Vishnu. About the middle of the Gita , Arjuna requests Krishna to show himself in his divine form, to take off his human costume and manifest himself the way he truly is. Arjuna's human sight is not able to perceive the divine essence, so Krishna grants him the gift of Spiritual Vision:

[Krishna speaking] But these things cannot be seen with your physical eyes; therefore I give you spiritual vision to perceive my majestic power. ( Bhagavad Gita 11:8)

Krishna agrees to Arjuna's request and displays a shocking revelation of his full vigour and glory. Arjuna then sees a blinding radiance that resembles a thousand suns, a million divine forms, infinite variety of colours and shapes, all the gods of the natural world, all the living creatures, the entire cosmos turning within Krishna's body along with the infinite number of faces of the god, infinite mouths, arms, eyes and stomachs. He also sees heavenly jewels, countless weapons, the very source of all wonders, Krishna's face everywhere, all the manifold forms of the universe united as one, Brahma , the creator god seated on a lotus flower, ancient sages and celestial serpents. Towards the end of this vision, Arjuna sees Krishna consuming the entire universe with his breath, all the worlds being destroyed in the mouth of the god, including all the warriors on the battlefield.

Krishna

Arjuna is terrified and humbled by this vision and he simply cannot handle its intensity, so Krishna recovers his human form.Arjuna decides to obey Krishna's command by engaging in the battle, after hearing the following words.

[Krishna speaking] [...] arise, Arjuna; conquer your enemies and enjoy the glory of sovereignty. I have already slain all these warriors; you will only be my instrument. ( Bhagavad Gita 11:33)

Inspired by Krishna's teachings, the Pandavas regain control of the kingdom.

RESEMBLANCES

There is an episode in Arjuna's adventures where he dresses up like a woman in the court of the king Virata, something similar to when the Nordic god Thor dresses in bride's clothes while he was trying to recover his mighty hammer. Episodes where heroes dress up as women can also be found in the stories of Hercules and Achilles , the heroes of Greek mythology .

Due to his impressive skills with the bow and arrow, Arjuna has been compared to the Greek god Apollo , also a skillful archer. However, in terms of status and character, Arjuna has also been compared to Achilles, which would be more accurate since both heroes share a half human, half divine nature and both are fearful warriors. This is why sometimes scholars refer to Arjuna as the Hindu Achilles, which is clearly a matter of which reference frame we adopt: it would be equally correct to say that Achilles is the Greek Arjuna.

Cosmetics, Perfume, & Hygiene in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

For the ancient Egyptians life was a celebration, and so, just as one would want to look one's best at any party, personal hygiene was an important cultural value. The Egyptians bathed daily, shaved their heads to prevent lice or other problems, and regularly used cosmetics, perfumes, and breath mints. So important was one's personal appearance that some spells from The Egyptian Book of the Dead stipulate that one cannot speak them in the afterlife if one is not clean and presentable, and it is clear this means in a physical sense.

Spell 125 prohibits one from speaking it unless one is "clean, dressed in fresh clothes, shod in white sandals, painted with eye-paint, anointed with the finest oil of myrrh." The gods are regularly depicted wearing eye make-up, as are the souls in the afterlife, and cosmetics are among the most common items placed in tombs as grave goods.

Cosmetic Box of Kemeni

Cosmetics were not only used to enhance personal appearance but also for one's health. The ingredients used in these ointments, oils, and creams helped to soften one's skin, protect from sunburn, protect the eyes, and improve one's self-esteem. Cosmetics were manufactured by professionals who took their work quite seriously since their product would be judged harshly if it were not the best it could be; such a judgment would result not only in a loss of reputation in the community but the possibility of a poor reception by the gods in the afterlife. To make sure they provided the best they could, ancient Egyptian manufacturers relied on the finest natural ingredients and most trusted production methods.

The science behind Egyptian cosmetics, deodorants, breath mints, and toothpaste was so advanced that, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the English word 'chemistry' (derived from 'alchemy') has its ancient roots in Kemet, the ancient name of Egypt in the Egyptian language (the name 'Egypt' is a Greek term). In his article on Medicine in Ancient Egypt , Dr. Sameh M. Arab supports this etymology and explains how, in spite of their shortcomings, Egyptian physicians had the most comprehensive knowledge of medicines in the ancient world. This same expertise is evident in the Egyptian manufacture of cosmetics, perfumes, and other aspects of personal hygiene.

DAILY USE OF COSMETICS

Cosmetics were used from the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 - c. 3150 BCE) through Roman Egypt (30 BCE-646 CE), the entire length of ancient Egyptian civilization . Men and women of all social classes applied cosmetics, although, clearly, the better products could only be afforded by the wealthy. These cosmetics were manufactured professionally and sold in the marketplace, but it seems some of lesser quality could be made in the home.

EVERY HOUSEHOLD, NO MATTER THE CLASS, HAD SOME FORM OF A BASIN & JUG USED FOR WASHING THE HANDS & SHOWERING.

A morning ritual, after one rose from bed, would be to bathe. Every household, no matter the class, had some form of a basin and jug used for washing the hands and showering. There were also foot baths, made of stone, faience , ceramic, or wood, for washing the feet. These were mass-produced during the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 BCE) as single-foot and double-foot baths.

One would wash one's hands, face, and feet before and after meals, before bed, and upon rising in the morning. Priests were expected to bathe more regularly, but the average Egyptian took showers and baths on a daily basis. In the morning, after one had washed, came the application of a cream, the ancient equivalent of sunblock, to the body, and then one would apply make-up, derived from ochre and sometimes mixed with sandalwood, to the face. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick writes:

In ancient Egypt, the focus was on the eyes, which were outlined with green or black eye paint to emphasize their size and shape. The ground pigments of green malachite, mixed with water to form as paste, were used until the middle of the Old Kingdom but were then replaced by black kohl, produced from the mineral galena, which came from the mountain regions of Sinai. Significantly, kohl had therapeutic value in protecting the eyes from infections caused by sunlight, dust, or flies. (380)

Kohl was created by grinding the natural elements of galena, malachite, and other ingredients into a powder and then mixing them with oil or fat until one produced a cream. This cream was then stored in stone or faience pots which were kept in a case of wood, ivory, silver , or other precious metal. Some of the most elaborate items found in tombs and the ruins of homes and palaces are these kohl cases which were intricately carved works of art. Kohl was quite expensive and only available to the upper classes, but it seems the peasant class had their own, cheaper, variant of the cosmetic. How this was manufactured, or from what chemicals, is unclear.

Creams, oils, and unguents were also used to preserve a youthful appearance and prevent wrinkling. They were applied with the hand, brushes, and in the case of kohl, a stick. These applicators, along with cosmetic spoons, are frequently found as grave goods. Honey was applied to the skin to help heal and fade scars, and crushed lotus flowers and the oil from various plants (such as the papyrus) were used in making these applications. In addition to the health benefits of protecting the skin from the sun, these cosmetics seem to have warded off sand flies and other insects.

Cosmetic Spoon

Unguents were kept by the wealthy in ornate jars which were often as intricately designed as the kohl cases. A particularly popular design was a jar in the form of Bes , the god of fertility, childbearing, children, and joy. Unguents would be rubbed all over the body and especially sweet-smelling and potent mixtures under the arms and around the legs.

As most Egyptians went barefoot, they would also rub an ointment on their feet, especially the soles, which acted as an insect repellent as well as sunscreen. For the king and the upper class, manicurists were employed to take care of one's finger- and toenails, which was done with a small knife and file. The manicurist to the king was a prestigious position, and these men always included their job title prominently on their tombs.

How the peasant class handled manicures and pedicures is not recorded, but most likely, they followed the same course only with less sophisticated tools or servants. The general life of the peasant class is fairly well documented, but not the specifics.Peasant farmers and their families would also have applied creams, ointments, and some form of deodorant but would not have been able to afford most perfumes.

PERFUMES & DEODORANTS

The most popular and best-known perfume was kyphi . It was made of frankincense, myrrh, mastic, pine resin, cinnamon, cardamom, saffron, juniper, mint, and other herbs and spices. The scent is described as completely elevating, and those who could afford it are reported as being envied by those who could not. Strudwick notes that "the Egyptians loved sweet, spicy perfumes that filled the air with their heady, long-lasting aroma," and kyphi was the most expensive and sought-after of these (378).

The ingredients for kyphi came largely from the land of Punt and so were rare in Egypt. There are only a few expeditions to Punt mentioned in Egyptian history aside from the famous trip commissioned under queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE).Whether the Egyptians were able to replicate these ingredients on their own is unknown, but it seems unlikely. Kyphi was so rare and expensive that it was primarily used in temples as an incense burned for the gods.

Less expensive and more common perfumes were made from flowers, roots, herbs, and other natural elements, which were ground into a paste and then either combined with fat or oil for a cream or made into a cone of incense. Paintings and inscriptions often depict ancient Egyptian men and women wearing these cones on their heads at parties and festivals, but there is considerable doubt as to whether they walked around with burning incense attached to their wigs.

Egyptian Perfume Bottle

No evidence of incense or fat residue has been found on any extant wigs from ancient Egypt, and it seems improbable they would have tried to balance a cone of incense at festivals where it was common to drink to excess. Most likely, the depictions of the people with the cones on their heads symbolize the good times had at such events or, perhaps, that the event had included sweet-smelling incense. There is also the possibility, however, that Egyptians did wear these incense cones on their heads at gatherings.

Deodorants were made in the same way as perfumes and often they were the same recipe applied in the same way. A number of recipes for deodorants, however, were for less fragrant products than a perfume. One method listed was to mix an ostrich egg, nuts, tamarisk, and crushed tortoise shell with fat, mix into a cream, and apply to one's arms, torso, and legs for a scent-free deodorant. A recipe and prescription from the medical text known as the Hearst Papyrus recommends mixing lettuce, myrrh, incense, and another plant (whose name is not known) and rubbing the paste on the body to prevent the odor of perspiration. The juices from fruits, mixed with frankincense or other spices such as cinnamon were also used.

WIGS, TOOTHPASTE, & BREATH MINTS

Before one left the house for the day, one would put on one's wig and clean one's teeth. Wigs, as noted, were worn to prevent lice, but they also were simply more comfortable in the arid climate and made personal hygiene easier. Wigs were made of human hair until the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt (c. 1782 - c. 1570 BCE) when the Hyksos introduced horses into Egypt; afterwards, horse hair was used in wig manufacture as well as human hair.

Wigs were made in different styles to be worn on separate occasions. It was recognized that one might wear their hair differently to a family gathering than to a fashionable event or festival, and wigs were designed differently to meet this need. As in all other areas of Egyptian life, the wealthy could afford the best wigs which were sometimes braided with jewelry or fine gems and perfumed. Poorer people of the lower classes wore wigs woven from papyrus plants or shaved their heads and simply wore a head covering.

Egyptian Tomb Relief

In cleaning one's teeth, one would use the Egyptian invention of the toothbrush and toothpaste. Toothpaste was invented before the toothbrush, and evidence of its use dates back to the Predynastic Period. The ingredients of the earliest toothpaste are not known, but a later recipe calls for a mixture of mint, rock salt, pepper, and dried iris flower. This would have been ground into a powder and applied to the teeth; one's saliva would have turned it into a paste. The toothbrush was, at first, a stick with one end frayed to a brush-like fan. Eventually, this developed into a notched stick with thin strips of cut plant (most likely papyrus) tightly bound into the notch as bristles.

Throughout the day, to keep one's breath fresh, one would suck on breath mints. These were made both commercially and at home by mixing frankincense, cinnamon, melon, pine seeds, and cashews together, grinding them into a powder, and then adding honey. The honey would serve as a binding ingredient which, when fully mixed with the rest, was heated over a fire, left to cool slightly, and then formed into small candies. It is probable that some of the jars and bowls found in homes were candy dishes which held these mints.

When one returned to the house at night, one would remove one's wig and bathe to remove one's make-up before the evening meal. From morning to evening, cosmetics and personal hygiene were a part of every ancient Egyptian's daily rituals. Since a primary goal of one's life was to make one's personal existence worthy of eternity, care for one's physical appearance and health was a priority.

The Egyptians may have had the most ideal vision of the afterlife but there is no record of any of them in any particular hurry to get there. Even so, life as an eternal journey was the accepted understanding of Egyptian culture . Applying cosmetics, as well as the use of other means of maintaining one's health and appearance, was necessary not only for a more pleasant time on earth but for the soul's eternal form in the next phase of existence.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License