Arabia › Archaeology › Music & Dance in Ancient Egypt » Origins and History

Articles and Definitions › Contents

- Arabia › Origins

- Archaeology › Origins

- Music & Dance in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient civilizations › Historical places, and their characters

Arabia › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Moros

The ancient Arabians, or Arabes as they were called by the Hellenes, were a Semitic people. One must note that the Arabians were not just a single people, but that it was divided in multiple smaller kingdoms and tribes. It was home to great city builders and nomads alike. They were of great influence on many occasions in the ancient period.

One of the first mentions of Arabs comes from the Bible and the Torah . The table of nations mentions Sheba, Dedan and Qedar. Most known is the famous and legendary rich Queen of Sheba who visited King Solomon , also mentioned in the Qur'an . Sheba is these days identified with ancient Saba, then the leading power in what today is Yemen. It was known for its prosperity, urban centres and magnificent buildings. The Qedar are known from Assyrian records as paying tribute from the 8th century BCE onwards, but also as Assyria 's enemies in the annals of Ashurbanipal . The Minaeans, also mentioned in Assyrian records, were famous traders who controlled most of the Red Sea area, and appear to have had close ties with the Egyptians with whom they traded incense. The caravan city of Tayma was also famous before classic ancient history: It was mentioned in the 8th century BCE by the Assyrians for paying tribute and it was the home of the Babylonian king Nabonidus during his elder days.

Other famous Arabian peoples at the time were the Gerrhans, from modern-day Bahrain who appear to have had naval trade connections with India . The other great traders from the North were the Nabataeans. They lived in modern day Jordan and replaced the Qedar as the most powerful political entity of the region. Their capital was Petra, a marvellous city carved out of the rock, famous today as a popular tourist site. The Nabataean kingdom reached its peak in the first century BCE, when it extended from Dedan to Damascus. By 106 CE it became the only Roman Arabian province under the name Arabia Petraea.Yet the richest of all Arabians would have been the Hadramawt, who lived in the southern lands that produced incense.

In the time of the Roman empire much had changed in Arabia. The Minaeans were no longer and the power in ancient Yemen had shifted as well. The Himyar, a tribe from the south, became the leading nation by conquering the whole of Yemen. In the North another famous Arabian queen, Zenobia , came to power. She expanded the Palmyran empire and even conquered Egypt , until she was captured by emperor Aurelian . Gerrha was part of the Sassanid empire by the 4th Century CE.

Archaeology › Origins

Definition and Origins

Author: Maisie Jewkes

Archaeology is a wide subject and definitions can vary, but broadly, it is the study of the culture and history of past peoples and their societies by uncovering and studying their material remains, ie tools, ruins, and pottery . Archaeology and history are different subjects but have things in common and constantly work with each other. While historians study books, tablets, and other written information to learn about the past, archaeologists uncover, date, and trace the source of such items, and in their turn focus on learning through material culture.

As much of human history is prehistoric (before written records), archaeology plays an important role in understanding the past. Different environments and climates help or hinder the survival of materials, eg papyri can survive thousands of years in the hot and dry desert but would not survive in damp conditions. Waterlogged conditions, such as bogs, can preserve organic material, like wood, and underwater wrecks are also excavated using diving equipment. Working everywhere from digging in the ground to testing samples in laboratories, archaeology is a wide-ranging discipline and has many sub-sections of expertise. The two rapidly widening areas are experimental archaeology and ethnoarchaeology. Experimental archaeology tries to recreate ancient techniques, such as glass making or Egyptian beer brewing. Ethnoarchaeology is living among modern ethnic communities, with the purpose of understanding how they hunt, work, and live. Using this information, archaeologists hope to better understand ancient communities.

ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PAST

THE FIRST SCIENTIFIC EXCAVATION HAS BEEN ATTRIBUTED TO THOMAS JEFFERSON IN VIRGINIA, USA.

Archaeology as an academic study, career, and university subject is a fairly recent development. Nevertheless an interest in the past is not new. Humankind has always been interested in its history. Most cultures have a myth or story that explains their foundation and distant ancestors. Ancient rulers have sometimes collected ancient relics or rebuilt monuments and buildings.This can often be seen as political strategy - a leader wanting to be identified with a great figure or civilisation from the past.On the other hand, ancient leaders have also been known for their curiosity and learning. King Nabonidus of Babylon , for example, had a keen interest in the past and investigated many sites and buildings. In one temple he found the foundation stone from 2200 years before. He housed his finds in a kind of museum at his capital of Babylon. The Roman and Greekhistorians wrote books about the past, and the stories of famous heroes and leaders have come down to us.

However, modern archaeology, or at least its theories and practice, stem from the antiquarian tradition. In the 17th and 18th centuries CE, wealthy gentleman scholars, or antiquarians as they are also known, began to collect classical artefacts. Fuelled by interest they began to make some of the first studies of sites, like Pompeii , and drew ancient monuments in detail. The first scientific excavation has been attributed to Thomas Jefferson (third president of the United States of America) who dug up some of the burial mounds on his property in the state of Virginia, USA. The beginnings of modern field techniques were pioneered by General Augustus Lane-Fox Pitt Rivers, who excavated barrows at Camborne Chase with systematic recording and procedure. In the USA in the 1960s CE, archaeology went through a phase of new theories, often called processual archaeology. This approach has a scientific approach to questions and designs models to suggest answers and test its theories.

FAMOUS ARCHAEOLOGISTS

Archaeology is a time consuming study; it often takes many years of toil before an archaeologist makes a breakthrough or discovers a site. Famous archaeologists are often connected to their most famous find or theory. To name the score of people who worked and made developments in archaeology would take a hundred pages; what follows are but a few: Howard Carter, an Englishman, who in 1922 CE discovered the tomb of the pharaohTutankhamun in Egypt ; Leonard Woolley spent years excavating the ancient city of Ur in Mesopotamia ; Heinrich Schliemann unearthed what is believed to be the mythical city of Troy , building on work done by an amateur archaeologist, Frank Calvert; Sir Arthur Evans excavated much of Knossos (on the island of Crete ) and developed the concept of Minoan Civilisation.

Grave Circle A, Mycenae

These men are all well known for their famous finds but also made developments in field archaeology and techniques, although Heinrich Schliemann's methods of digging down very quickly and only recording the earlier levels are today questioned and criticised, as are the reports that he smuggled artefacts out of the country. Others such as Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Sir William Flinders Petrie, and Gordon Childe are famous for their methods of recoding, precision in excavations, and approaches to archaeology theory. Mary and Louis Leakey worked for many years in East Africa transforming our knowledge of human development and pushing back the dates of humans ancestors by millions of years.

The work of other individuals, not all classified as archaeologists but rather as scholars, who worked for decades on the study of languages, should be mentioned. Jean-Francois Champollion cracked the Egyptian hieroglyphics in 1822 CE. Tatiana Proskouriakoff worked in the later half of the twentieth century CE on the problems of Maya hieroglyphic writing and contributed to the final breakthrough. In the 1850s CE Henry Rawlinson cracked the Mesopotamian cuneiform script .

MODERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL TECHNIQUES

Modern archaeology is a diverse field with many techniques in use. However, there are common ones that most archaeologists working in the field use:.

1. Field walking and surface survey:

2. Basically this is when a team of people walk across the countryside, an equal distance apart, with each recording finds and features in his or her path. This is used, for example, to track settlement patterns. Surveys are also done in the air, by airplanes, or using satellites. In England the outlines of hill forts or Roman villas are easily visible under the soil.

3. Excavation:

4. Probably the most recognisable feature of archaeology, (that, and of course, treasure). There are three types of excavations (or digs): research, rescue, and salvage. The first is usually to test a theory or answer a question. The last two types of digs are those conducted on sites that are threatened with, or are after, destruction. Excavations are usually carried out on a grid plan and go down in layers, carefully recording each layer and the finds, before clearing it away to reach an earlier level. This is called stratification. There is debate about when it is alright to dig, as excavations are in themselves destructive. However, they still remain the primary source of collecting archaeological knowledge.

5. Typologies:

6. After finds have been cleaned, they are then sorted into groups and classified according to material, size, and decoration.This can help to provide a rough date for an object and provide a basis on which further study can be made. Studying the decoration or shape of an object can tell us about trade networks, craft skills, and people's artistic tastes and values.

7. Laboratory analyses:

8. A great deal of knowledge can be gained from looking at an artefact under a microscope or chemically testing it.Radiocarbon dating measures the rate of decay of carbon 14 and can be used to date many different types of organic materials (as long as they are less than 60,000 years old). This and other similar processes can help to give a fairly accurate date to an object. Another feature of testing is food sources. Even after thousands of years, food sediments can be traceable on artefacts. This can tell us what foods people were eating and even how they cooked.

By carefully studying a simple object, or mapping an ancient city or opening a forgotten tomb or excavating a sunken galleon, the past is opened up and we can all learn more about peoples and societies otherwise outside our reach. That is archaeology.

Music & Dance in Ancient Egypt › Origins

Ancient Civilizations

Author: Joshua J. Mark

Music and dance were highly valued in ancient Egyptian culture , but they were more important than is generally thought: they were integral to creation and communion with the gods and, further, were the human response to the gift of life and all the experiences of the human condition. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick notes how, "music was everywhere in Ancient Egypt - at civil or funerary banquets, religious processions, military parades and even at work in the field" (416). The Egyptians loved music and included scenes of musical performances in tomb paintings and on temple walls, but valued the dance equally and represented its importance as well.

The goddess Hathor , who also imbued the world with joy, was associated most closely with music, but initially, it was another deity named Merit (also given as Meret). In some versions of the creation story, Merit is present with Ra or Atum along with Heka (god of magic) at the beginning of creation and helps establish order through music. Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson notes how she did this "by means of her music, song, and the gestures associated with musical direction" (152). Merit, then was the writer, musician, singer, and conductor of the symphony of creation establishing music as a central value in Egyptian culture.

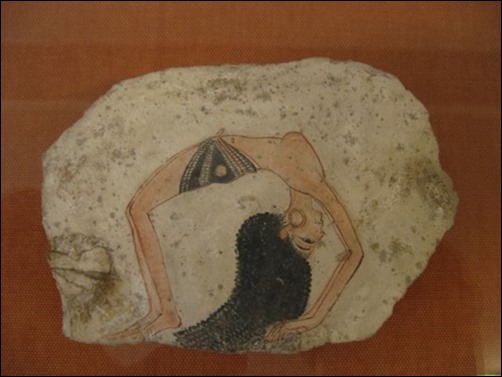

Egyptian Dancer

Along with music, naturally, came dance. Merit also inspired dance, but this too came to be associated with Hathor whose dancers are well-attested to through images and inscriptions. Egyptologist Carolyn Graves-Brown writes:

The role of women in religion was often to provide music and dance for religious ceremonies. Not only priestesses, but also women in general were associated with music. Wives, daughters, and mothers are frequently shown shaking sistra for the deceased in the Eighteenth Dynasty. The heavy smell of incense, the rhythm of the menit-necklace and the sistra, the chanting of the female priestess musicians in the semi-gloom of the Egyptian temple are sensual experiences which we can only imagine today. (95)

The menit -necklace was a heavily beaded neck piece which could be shaken in dance or taken off and rattled by hand during temple performances and the sistrum (plural sistra), was a hand-held rattle/percussion device closely associated with Hathor but used in the worship ceremonies of many gods by temple musicians and dancers.

Dancers were not relegated only to temples, however, and provided a popular form of entertainment throughout Egypt.Dancing was associated equally with the elevation of religious devotion and human sexuality and earthly pleasures. In Egyptian theology, sex was simply another aspect of life and had no taint of 'sin' attached to it. This same paradigm was observed in fashion for both male and female dancers. Women often wore little clothing or sheer dresses, robes, and skirts.

MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS & PERFORMANCES

The instruments played in ancient Egypt are all familiar to people today. There were percussion instruments (drums, the sistrum, rattles, tambourines and, later, bells and cymbals); stringed instruments (lyres, harps, and the lute which came from Mesopotamia ); and wind instruments like the shepherd's pipe, double-pipe, clarinet, flute, oboe, and trumpet). Musicians played these either solo or in an ensemble, just as today.

Menit Necklace

The ancient Egyptians had no concept of musical notation. The tunes were passed down from one generation of musicians to the next. Exactly how Egyptian musical compositions sounded is, therefore, unknown, but it has been suggested that the modern-day Coptic liturgy may be a direct descendent. Coptic emerged as the dominant language of ancient Egypt in the 4th century CE, and the music the Copts used in their religious services is thought to have evolved from that of earlier Egyptian services just as their language evolved from ancient Egyptian and Greek .

EXACTLY HOW EGYPTIAN MUSICAL COMPOSITIONS SOUNDED IS UNKNOWN, BUT IT HAS BEEN SUGGESTED THAT THE MODERN-DAY COPTIC LITURGY MAY BE A DIRECT DESCENDENT.

Music is designated in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics as hst ( heset ) meaning "song", "singer", "musician", "conductor" and also "to play music" (Strudwick, 416). One would understand the precise meaning of the heset hieroglyph by where it was placed in a sentence. This hieroglyph includes a raised arm which symbolizes the role of the conductor in keeping time.Conductors, even of small ensembles, appear to have been quite important. Strudwick notes tomb paintings from Saqqara which show a conductor, "with a hand over one ear to aid hearing and to improve concentration as he faces the musicians and indicates the passage to be played" (417). Conductors then, as now, used hand gestures to communicate with their musicians.

Performances were held at festivals, banquets, in the temple, and at funerals, but could take place anywhere. The upper classes regularly employed musicians for entertainment at evening meals and for social gatherings. Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley notes:

Music was a particularly lucrative career which was open to both men and women and which could be pursued either on a freelance basis or as a servant permanently attached to an estate or temple. Good performers were always in demand and a skillful musician and composer could gain high status in the community; for example, the female performing duo of Hekenu and Iti were two Old Kingdom musicians whose work was so celebrated that it was even commemorated in the tomb of the accountant Nikaure, a very unusual honor as few Egyptians were willing to feature unrelated persons in their private tombs. The sound of music was everywhere in Egypt and it would be difficult to overestimate its importance in daily Dynastic life. (126)

Hekenu and Iti were not only musicians but also dancers, and this combination was more common among women than men.Women are often depicted dancing and playing an instrument and are recorded as singers, while men, then as now, were less inclined toward dance. A popular duo, ensemble, or solo artist would give a performance at a set time and place but musicians regularly played in the market place and for laborers. The pyramids of Giza would have been built to the sounds of music in the same way that people today listen to the radio while they work.

DANCERS & THE DANCE

By the time of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) music was well established as a part of Egyptian life. The famous poetic genre of the love song, so closely associated with the New Kingdom , may have developed to be sung and accompanied by interpretative dance. Whether the love song developed as a song lyric is uncertain but interpretative dance was a regular part of religious rituals. Egyptologist Gay Robins describes an engraving from the reign of Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) depicting a musical performance. A male harpist performs and sings a hymn to the deity while women appear to dance interpretatively:

A number of acrobatic dancers are shown doing back-bends, or dancing energetically with their hair falling over their faces. In one scene, their actions are captioned 'dancing by the dancers'. Other women are not dancing but shake their sistra with one hand and hold a menit necklace in the other; they also sing a hymn. (146)

Music and dance served to elevate participants in religious ceremonies toward a closer relationship with the deity. Hymns to the gods were sung to the accompaniment of musical instruments and dance, and there was no proscription on who could or could not dance at any given time. Although the upper class do not seem to have danced publicly as the lower class did, there are clear instances in which the king danced.

Ancient Egyptian Music and Dancing

Perhaps part of the reason upper-class men and women are not shown dancing is because of the close association it had with public entertainment in which dancers wore next to nothing. The problem would not have been with nudity but with associating one's self with the lower class. Ancient Egyptians, in any era of the culture, were completely comfortable with their naked bodies and those of others. Scholar Marie Parsons comments on this:

Women who danced (and even women who did not) wore diaphanous robes, or simply belt girdles, often made of beads or cowrie shells, so that their bodies could move about freely. Though today their appearance may be interpreted as erotic and even sensual, the ancient Egyptians did not view the naked body or its parts with the same fascination that we do today, with our sense of possibly more repressed morality. (2)

Whether in the temple or in public performances, the gods were invoked through dance. The gods and goddesses of Egypt were present everywhere, in every aspect of one's life, and were not restricted simply to temple worship. A practice of 'impersonating' a deity grew up in which the dancer would take on the attributes of the divine and interpret the higher realms for an audience. The most popular deity associated with this is Hathor.

Dancers would imitate the goddess by invoking her epithet, The Golden One , and enacting stories from her life or interpreting her spirit through dance. Dancers would often have tattoos representing the protective aspect of Hathor or the god Bes , and priestesses were known as Hathors and, in some periods, wore horned headdresses to associate themselves with Hathor's aspect as a cow-goddess.

TYPES OF DANCE

Marie Parsons cites the types of dances most common in Egyptian practice:

1. The purely movemental dance. A dance which was little more than an outburst of energy, where the dancer and audience alike simply enjoyed the movement and its rhythm.

2. The gymnastic dance. Some dancers excelled at more strenuous and difficult movements, which required training and great physical dexterity and flexibility. These dancers also refined their movements so as to move delicately.

3. The imitative dance. These appeared to be emulative of the movements of animals, only obliquely referred to in Egyptian texts while not actually being represented in art.

4. The pair dance. Pairs in ancient Egypt were formed by two men or by two women dancing together, not by men dancing with women. The movements of these dancers were executed in perfect symmetry, indicating, at least to the author of this treatise, that the Egyptians were deeply conscious and serious about this dance as something more than just movement.

5. The group dance. These fell into two sub-types, one taking place with perhaps at least four, sometimes as many as eight, dancers, each performing different movements, independent of each other, but in matching rhythms. The other sub-type was the ritual funeral dance, performed by ranks of dancers executing identical movements.

6. The war dance. These were apparently recreations for resting mercenary troops of Libyans, Sherdans, Pedtiu (peoples who formed parts of the so-called Sea Peoples ) and other groups.

7. The dramatic dance. From the examples used herein, the author is considering a depicted familiar posture of several girls as being performed to commemorate a historical tableau: a kneeling girl represents a defeated enemy king, a standing girl the Egyptian king, holding the enemy with one hand by the hair and with the other a club.

8. The lyrical dance. The description of this dance indicates it told its own story, much as a ballet we may see today. A man and a girl dancer using wooden clappers which gave their steps rhythm danced in harmonious movement, separately or together, sometimes pirouetting, parting, and approaching, the girl fleeing from the man, who tenderly pursued her.

9. The grotesque dance. These were apparently primarily performed by dwarves such as the one Harkhuf was asked to bring back to dance "the divine dances".

10. The funeral dance. These formed three sub-types. One was the ritual dance, forming part of the actual funeral rite. Then there were the expressions of grief, where the performers placed their hands on their heads or made the ka gesture, both arms upraised. The third sub-type was a dance to entertain the ka of the deceased.

11. The religious dance. Temple rituals included musicians trained for the liturgy and singers trained in the hymns and other chants.

All of these dances, for whatever purpose, were thought to elevate the spirit of the dancer and of the audience of spectators or participants. Music and dance called upon the highest impulses of the human condition while also consoling people on the disappointments and losses in a life. Dance and music at once elevated and informed not only one's present circumstance but the universal meaning of triumph and suffering.

Egyptian Bronze Sistrum

CONCLUSION

The association of music and dance with the divine was recognized by ancient cultures around the world, not only in Egypt, and both were incorporated into spiritual rituals and religious ceremonies for thousands of years. The present-day aversion to dance and so-called 'secular music' stems from the condemnation of both with the rise of Christianity .

Although some church fathers such as Clement of Alexandria (150-215 CE) saw evidence in the scriptures encouraging dance (such as King David 's famous spontaneous dancing for God in II Samuel 6:14-16), most saw dance as a continuation of heathen practices and forbade it. By the time of the Byzantine Empire (330 CE), dancing had been proscribed as immoral and music was separated into the categories of liturgical and secular.

The Byzantine Empire still approved, somewhat tentatively, of both but the church of Rome did not. It is for this reason that the Eastern Orthodox Church still encourages dance and music in religious services while the Catholic Church, until very recently, has not. Long before either of these sects of the new religion blossomed, the ancient Egyptians recognized the power of music and dance to elevate the soul and open new perspectives and, for over three thousand years, people were encouraged and inspired by music, the force which helped give birth to and shape the universe, and dance, which is the human response to creation.

LICENSE

Article based on information obtained from these sources:with permission from the Website Ancient History Encyclopedia

Content is available under License Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License